Xiang Yu splits the former Qin Empire …

Years: 213BCE - 202BCE

Xiang Yu splits the former Qin Empire into the so-called Eighteen Kingdoms following the collapse of the dynasty in 206 BCE.

Two prominent contending powers, Western Chu and Han, emerge from these principalities and engage in a struggle for supremacy over China.

Western Chu is led by Xiang Yu, while the Han leader is Liu Bang.

During this period of time, several minor kings from the Eighteen Kingdoms also fight battles against each other.

These battles are independent of the main conflict between Chu and Han.

The war ends with total victory for Han, after which Liu Bang proclaims himself "Emperor of China" and, as Emperor Gaozu of Han, establishes the Han Dynasty in 202 BCE.

Commodoties

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 63638 total

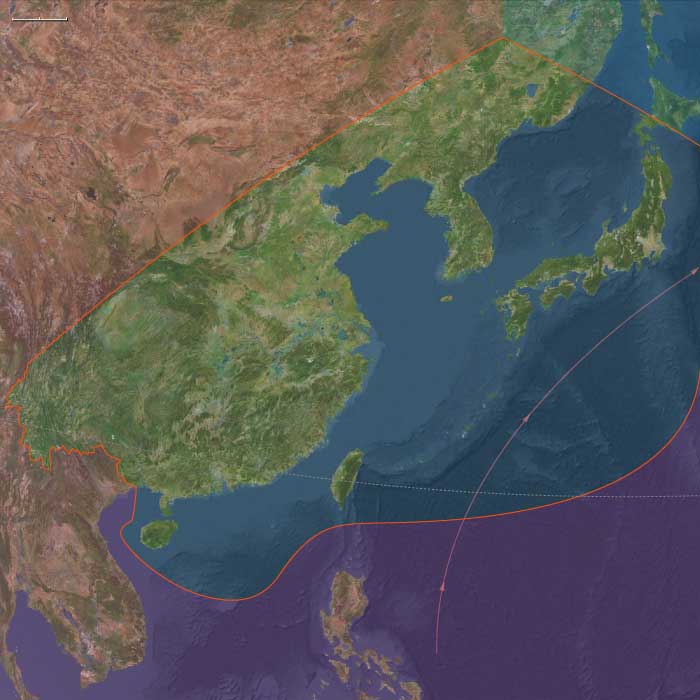

The Xiongnu, a nomadic confederation possibly of Turkic ethnicity and viewed by the Qin as bandits, had been recently expelled from the north, but return after the death of the First Qin Emperor, Shi Huangdi, to occupy the region from the Mongolian-Tibetan borders eastward to the Yellow Sea.

Antiochus III's Eastern Reconquests

Following decades of territorial losses to the rising Parthian and Bactrian kingdoms after 238 BCE, Antiochus III the Great, driven by the ambition to reunite Alexander the Great’s former empire, initiates a decisive campaign eastward in 209 BCE. At this time, the Seleucid realm had significantly diminished, with regions east of Persia and Media largely lost due to earlier distractions in wars with Ptolemaic Egypt.

Antiochus achieves remarkable military success against the Parthians, forcing them to acknowledge Seleucid authority and restricting their domain back to the historical boundaries of the province of Parthia itself. However, this vassalage remains largely symbolic and enforced primarily by the presence of Seleucid military power.

For these significant achievements, Antiochus earns the title ‘Great’ from his nobles. Despite his military prowess, he ultimately recognizes the independence of the Parthian kingdom and the Greco-Bactrian ruler Euthydemus, stabilizing the region through a pragmatic system of vassal states and client kingdoms.

With the eastern provinces secured, Antiochus III soon redirects his ambitions westward, compelled by ongoing rivalries with Ptolemaic Egypt and the emerging power of the Roman Republic, setting the stage for future confrontations and further reshaping the geopolitical landscape of the ancient Near East.

The Parthians had begun to try to conquer as much of the eastern Seleucid empire as possible after 238 BCE, joined in this endeavor by the now independent province of Bactria.

The Seleucid king Antiochus II Theos was at the time too busy fighting a war against Ptolemaic Egypt and so the Seleucids had lost most of their territory east of Persia and Media.

Antiochus III, an ambitious Seleucid king who has a vision of reuniting Alexander the Great's empire under the Seleucid dynasty, launches a campaign in 209 BCE to regain control of the eastern provinces, and after defeating the Parthians in battle, he successfully regains control over the region.

The Parthians are forced to accept vassal status and now only control the land conforming to the former Seleucid province of Parthia.

However, Parthia's vassalage is only nominal at best and only because the Seleucid army is on their doorstep.

For his retaking of the eastern provinces and establishing the Seleucid borders as far east as they had been under Seleucus I Nicator, Antiochus is awarded the title ‘great’ by his nobles.

Antiochus establishes a magnificent system of vassal states but has had to recognize the independence of two kingdoms, that of the Parthians and that of the Greco-Bactrian ruler Euthydemus, which had been no more than satrapies.

Luckily for the Parthians, the Seleucid Empire has many enemies, and it will not be long before Antiochus leads his forces west to fight Ptolemaic Egypt and the rising Roman Republic.

Near East (213–202 BCE): Egyptian Instability and Hellenistic Opportunism

In the early years of this era, native Egyptians, empowered by their decisive role in the victory at the Battle of Raphia (217 BCE), become increasingly aware of their potential strength. Emboldened, they initiate a rebellion against their Hellenistic overlords. Polybius, the contemporary historian, describes this uprising as guerrilla warfare, marking a significant escalation in Egyptian resistance and highlighting the tenuous grip of the Ptolemaic dynasty over Egypt.

Meanwhile, court intrigue intensifies around the death of Ptolemy IV Philopator in 205 BCE and the accession of his young successor, Ptolemy V Epiphanes (205–180 BCE). According to Polybius, a clique led by the influential minister Sosibius consolidates power by announcing the young king’s accession and the sudden deaths of his parents, simultaneously banishing all prominent rivals from Egypt.

Recognizing Egypt's internal vulnerability, the rulers of Macedon and the Seleucid Empire, centered in Syria, secretly agree to exploit the situation, conspiring to partition Egypt’s valuable territories in Asia Minor and the Aegean region. This opportunistic alliance foreshadows further instability, as Egypt’s neighbors seek advantage from its weakened condition.

The native Egyptians, sensing their power, rise against their Hellenistic rulers in a rebellion that Polybius describes as guerrilla warfare.

Court intrigue obscures the events surrounding the death of Ptolemy IV Philopator and the succession of the youthful Epiphanes (205-180 BCE).

According to Polybius, all prominent officials are banished from Egypt while Sosibius' clique announces the young king's accession and the death of his parents.

The rulers of Macedon and of the Syrian-based Seleucid kingdom, however, realizing Egypt's weakness, conspire to partition that Kingdom's Asiatic and Aegean possessions.

A sideshow of the Punic war is the indecisive First Macedonian War in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Ionian Sea, during which conflict Philip V of Macedon again defeats the Aetolian League and Rome after the two ally against him in 211.

The war ends with two different peace treaties; one with the Aetolian League in 206 and one with Rome in 205 called the "Peace of Phoenice," which allows Philip to keep the land he had taken in Illyria.

This war is essentially a renewal of the Social War and ends in the same way, with the Aetolian League losing a second war to Philip V and Macedonia.

Philip, seeing his chance to defeat Rhodes, forms an alliance with Aetolian and Spartan pirates who begin raiding Rhodian ships.

Philip also forms an alliance with several important Cretan cities, such as Hierapynta and Olous.

With the Rhodian fleet and economy suffering from the depredations of the pirates, Philip believes his chance to crush Rhodes is at hand.

To help achieve his goal, he forms an alliance with the King of the Seleucid Empire, Antiochus the Great, against Ptolemy V of Egypt (the Seleucid Empire and Egypt are the other two Diadochi states).

Philip begins attacking the lands of Ptolemy and Rhodes's allies in Thrace and around the Sea of Marmara.

Rhodes and her allies Pergamon, Cyzicus, and Byzantium combine their fleets in 202 BCE and defeat Philip at the Battle of Chios.

Rome's first major military expedition into the Greek world meets with brilliant success, disrupting Hellenistic hegemony in the eastern Mediterranean.

Philip V loses all his territory outside Macedonia, and the victorious commander Flamininus establishes a Roman protectorate over the "liberated" Greek city-states.

Flamininus develops the policy of turning the cities, leagues, and kingdoms of the Hellenistic world into clients of Rome and of himself, a policy that will become the basis of Roman hegemony of the Mediterranean.

The fortunes of Greece and Rome for about the next five hundred years will henceforth be intertwined.

The Romans, in the ongoing war with Carthage, now deploy the Fabian strategy against Hannibal's skill on the battlefield.

Roman forces are more capable in siegecraft than the Carthaginians and recapture all of the major cities that have joined the enemy, as well as defeating a Carthaginian attempt to reinforce Hannibal at the battle of the Metaurus.

In Iberia, which serves as the main source of manpower for the Carthaginian army, a second Roman expedition under Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus Major, takes Carthago Nova by assault and ends Carthaginian rule over Iberia in the battle of Ilipa.

The final showdown is the Battle of Zama in Africa between Scipio Africanus and Hannibal, resulting in the latter's defeat and the imposition of harsh peace conditions on Carthage, which ceases to be a major power and becomes a Roman client-state.

The battles of the Second Punic War are ranked among the most costly traditional battles of human history; in addition, there are a few successful ambushes of armies that also end in their annihilation.

Mediterranean Southwest Europe (213–202 BCE): Roman Resilience and Victory in the Second Punic War

The era 213–202 BCE witnesses Rome’s determined counteroffensive against Carthage, demonstrating strategic resilience, adaptability, and ultimately achieving a decisive victory in the Second Punic War. Despite Hannibal’s earlier successes, Rome’s disciplined military and strategic diplomacy enable it to reverse its fortunes, reshaping the geopolitical landscape of the Mediterranean.

Rome’s Fabian Strategy and Strategic Countermeasures

Adopting the Fabian strategy—a deliberate avoidance of direct large-scale engagements—Roman generals methodically weaken Hannibal's forces by disrupting supply lines, retaking defected cities, and preventing the formation of a unified Carthaginian alliance. This approach successfully slows Hannibal's momentum, effectively isolating his army in southern Italy and depriving him of critical resources and reinforcements.

Roman Siegecraft and Military Triumphs

Capitalizing on superior siegecraft and logistical capability, Roman forces systematically recapture strategic towns and cities previously allied with Hannibal. By 207 BCE, Rome decisively defeats Carthaginian attempts at reinforcing Hannibal through the crucial Battle of the Metaurus, marking a turning point by eliminating Hannibal’s vital reinforcement under his brother, Hasdrubal Barca.

Roman Dominance in Iberia

Simultaneously, Roman armies under the command of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus Major secure significant victories in Iberia. The decisive Roman capture of Carthago Nova (209 BCE) effectively dismantles Carthaginian dominance on the Iberian Peninsula. Further, Rome achieves a definitive triumph at the Battle of Ilipa (206 BCE), effectively ending Carthaginian influence in Iberia, significantly undermining Carthage's ability to sustain its Italian campaign.

Culmination at Zama and Carthage’s Defeat

In 202 BCE, the Battle of Zama near Carthage marks the climactic end of the Second Punic War. Here, Scipio Africanus faces Hannibal directly in a decisive confrontation. Hannibal's forces, although seasoned and battle-hardened, suffer a conclusive defeat against Scipio’s disciplined Roman legions. The resultant peace terms drastically curtail Carthaginian power, relegating Carthage to the status of a Roman client state, effectively ending its position as a dominant Mediterranean power.

Long-term Impacts and Legacy

The Second Punic War profoundly reshapes the geopolitical dynamics of Mediterranean Southwest Europe. Rome emerges as an undisputed regional hegemon, significantly expanding its influence across Italy, Iberia, and North Africa. Hannibal’s earlier victories and Rome’s eventual triumph underline Rome’s military resilience and strategic depth, setting a precedent for its later expansion and dominance in the broader Mediterranean region. The war’s end signals not only the rise of Rome as a superpower but also the definitive decline of Carthage’s imperial ambitions.

Hannibal’s forces continue to menace Italy in the ongoing Second Punic War, but Roman armies continue to hold Spain against Carthage, and the Roman fleet controls all the Mediterranean.

North Africa (213–202 BCE)

Carthaginian Challenges, Cyrenaic Stability, and Berber Continuity

Carthage Under Pressure and Hannibal’s Struggles

Between 213 and 202 BCE, Carthage faces escalating difficulties as the Second Punic War intensifies. Although Hannibal achieves remarkable initial victories on Italian soil, logistical challenges, and insufficient reinforcements from North Africa strain Carthaginian efforts. Nevertheless, Carthage maintains control of key Mediterranean trade routes and continues to protect its critical North African territories, particularly Leptis and Oea (modern Tripoli).

Continued alliances with interior Berber tribes remain vital, providing essential support and resources despite the increasing pressures of war. Coastal cities, notably Tangier, remain economically vibrant, ensuring sustained integration and stability between coastal and inland communities.

Diplomatic Struggles and Mediterranean Realignments

As the war drags on, Carthage’s diplomatic strategies become increasingly strained. Efforts to secure additional alliances and maintain existing relationships across the Mediterranean become vital to Carthage's survival strategy. Hannibal's sustained military presence in Italy heavily influences diplomatic negotiations and alliances, compelling Carthage to maintain a delicate balance between aggressive strategy and cautious diplomacy.

Cyrenaica’s Persistent Economic and Diplomatic Resilience

The Greek Pentapolis—Cyrene, Barce (Al Marj), Euhesperides (Benghazi), Teuchira (Tukrah), and Apollonia (Susah)—continues its economic prosperity through stable trade, notably in grain, fruit, horses, and the prized medicinal plant Silphium. Cyrene’s sustained investments in infrastructure and civic institutions emphasize its ongoing political autonomy and resilience.

Amid heightened Mediterranean conflicts, Cyrenaica skillfully maintains diplomatic neutrality and autonomy, successfully safeguarding its Greek cultural heritage and political independence through careful management of external relationships.

Numidia

Foundation and Alliance

Numidia emerges as a significant regional power under King Masinissa, who establishes an important alliance with Rome. Masinissa plays a crucial role in Rome's victory against Carthage in the Second Punic War, especially at the decisive Battle of Zama (202 BCE), consolidating Numidia’s power and expanding its territory.

Berber Economic Integration and Cultural Stability

Berber communities remain economically integrated with Carthaginian trade networks, persistently adopting sophisticated agricultural practices, maritime expertise, and artisanal skills. Essential trade centers, particularly Oea (Tripoli), continue to prosper, providing significant stability and economic strength to the region.

Inland Berber tribes preserve significant autonomy, upholding traditional governance structures and cultural identities. Their continued indirect participation in prosperous coastal trade networks ensures ongoing economic resilience and cultural continuity.

Cultural Synthesis and Religious Syncretism

Interactions among Berber, Carthaginian, and Greek populations remain vibrant, further enriching regional artistic traditions, notably in pottery, textiles, and metalwork. Religious syncretism continues to evolve, harmoniously integrating indigenous Berber spiritual traditions with Phoenician and Greek religious practices, enhancing the complexity and diversity of the regional culture.

Enduring Stability Despite Geopolitical Turmoil

By 202 BCE, despite considerable geopolitical turmoil culminating in Hannibal’s eventual defeat at the Battle of Zama, North Africa maintains notable political resilience, sustained economic vitality, and dynamic cultural integration. Cyrenaica’s diplomatic agility, enduring Berber stability, and the persistent economic strength of coastal hubs collectively sustain regional cohesion and prominence amid shifting Mediterranean power dynamics.