King Naemul of Silla is the first …

Years: 381 - 381

King Naemul of Silla is the first king to appear by name in Chinese records.

It appears that there was a great influx of Chinese culture into Silla in his period, and that the widespread use of Chinese characters begins in his time.

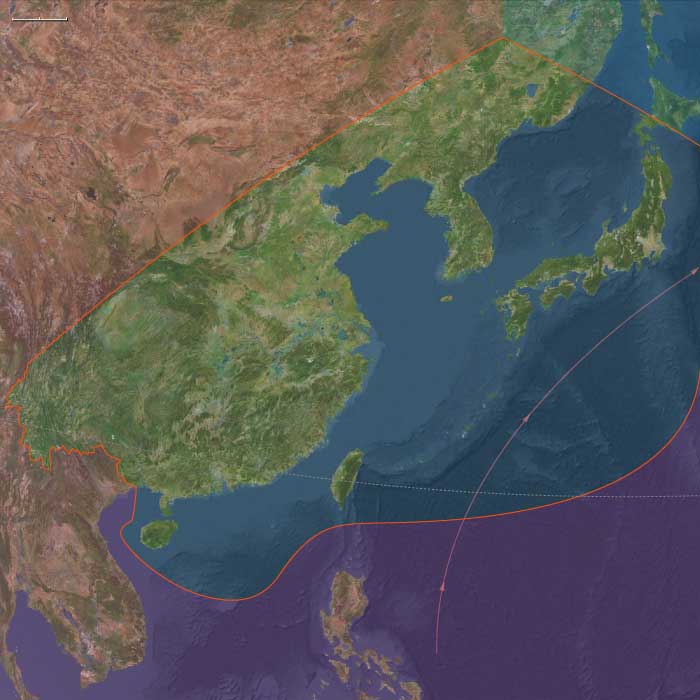

In 381, Silla sends emissaries to China and establishes relations with Goguryeo.

Locations

People

Groups

- Korean people

- Silla, Kingdom of

- Goguryeo (Koguryo), Kingdom of

- Chinese (Han) people

- Chinese Empire, Tung (Eastern) Jin Dynasty

Topics

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 59571 total

The Nicene Creed prescribed in 380 is again defined at the beginning of 381 and ecclesiastically sanctioned, as it were, in the summer of this year by a church council summoned to Constantinople by Theodosius, chiefly to confront Arianism.

Meletius of Antioch presides but dies during the Council; Gregory of Nyssa, whose brother Basil had died early in 379, delivers Meletius’s funeral oration.

The Council, attended by more than 150 bishops, all from the Eastern portion of the empire, reaffirms the Nicene Creed, firmly rejecting Arianism, as well as Modalism and Monarchianism.

Apollinarianism, which had been opposed by Basil, together with Gregory of Nyssa, Gregory of Nazianzus, and Athanasius because of the doctrine’s implication that Christ was not fully human, is also condemned, as are the Eunomians, as the followers of Eunomius’s extreme brand of Arianism have become known.

In formulating the doctrine of the Holy Spirit, the Council defines the position of the Holy Spirit within the Trinity, describing the Holy Spirit as proceeding from God the Father.

It follows Athanasius in affirming the equality of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, declaring them separate persons but coequal and of one substance.

The council’s canons establish the authority of the metropolitan bishops over their dioceses and give the bishop of the capital a primacy similar to that of the bishop of Rome.

It also deposes Constantinople’s Arian bishop, Maximus.

Gregory of Nazianzus, who has influenced Jerome during the three years he has spent in Constantinople, plays a leading role at the council, but opposition to his claim to the Maximus’ vacated bishopric makes him decide to return to Nazianzus.

The gathering, considered the second ecumenical council, universally imposes the Nicaean faith: Christianity as preached by Peter is to be the sole official religion of the Roman Empire; orthodoxy is defined as the doctrines proclaimed by the bishops of Rome and Alexandria.

The Council’s new theological formulas persuade most Arians to convert to orthodoxy.

A church council held in Aquiléia in September 381, summoned by Gratian explicitly to "solve the contradictions of discordant teaching", has in fact been organized by Ambrose, though it is presided over by Valerian, Bishop of Aquileia.

The council, attended by thirty-two bishops of the West, from Italy, Africa, Gaul, and Illyria, deposes from their offices two bishops of the Eastern province of Dacia as partisans of Arius.

One of these, Palladius, had applied to the Emperor of the East for an opportunity to clear himself before a general council of these charges concerning the nature of Christ.

He had been unwilling to submit to a council of the Western bishops only, for Ambrose had previously assured the Emperor of the West that such a matter as the soundness or heresy of just two bishops might be settled by a council simply consisting of the bishops of the Diocese of Italy alone.

Palladius refused to admit the legitimacy of the proceedings, but the bishops unanimously pronounce anathema on all counts, and the matter is settled.

The council also requests the Emperors Theodosius and Gratian to convene at Alexandria a general council of all bishops in order to put an end to the Meletian schism at Antioch that has been ongoing since 362.

Theodosius seeks new possibilities for coexistence, recognizing after a series of costly and inconclusive campaigns that the barbarians can no longer be expelled from the provinces by force and that he can count on Gratian for only limited assistance.

This had resulted in the friendly reception, in 381, of Therving chieftain Athanaric (who died at Constantinople a fortnight after his arrival) and the conclusion of an unprecedented treaty of alliance, or foedus, with the main body of the Thervings in the fall of 382.

Pledging themselves to lending military assistance, the Goths are assigned territory for settlement between the lower Danube and the Balkan mountains.

Under this novel arrangement, an entire people is to be settled on imperial soil while retaining its autonomy.

Theodosius may hope that these Goths will become integrated, as had a group of Goths who in around 350 had settled near Nicopolis in Moesia; their leader, Bishop Ulfilas, undertakes missionary work among the parties to the foedus of 382.

Priscillian, a rigorous Spanish Christian ascetic apparently influenced by gnosticism and Manichaean dualism, espouses an unorthodox doctrine similar to both in its dualistic belief that matter is evil and the spirit good.

He teaches that angels and human souls emanate from the Godhead, that bodies are creations of the devil, and that human souls are joined to bodies as a punishment for sins.

Leading his followers in a quasi-secret society that aims for higher perfection through ascetic practices and proscribes all sensual pleasure, marriage, and the consumption of wine and meat, his movement, called Priscillianism, spreads throughout western and southern Spain and in southern Gaul.

Despite his unorthodox views, Priscillian had become bishop of Ávila in 380.

The Spanish church, led by bishops Hyginus of Mérida and Ithacius of Ossonoba, had soon opposed the movement.

A council of Spanish and Aquitanian bishops had adopted at Saragossa eight canons bearing more or less directly on the prevalent heresy of Priscillianism.

Priscillian’s enemies now persuade the devoutly Christian Gratian to exile the bishop and his primary disciples to Italy.

Gratian has spent most of his reign in Gaul repelling the tribes that are invading Gaul from across the Rhine.

Influenced from the outset by Ausonius, whom he had made consul in 379, he has sought to make his rule mild and popular.

For some years, he has governed the empire with energy and success but has gradually sank into indolence, occupying himself chiefly with the pleasures of the chase, and become a tool in the hands of the Frankish general Merobaudes and bishop Ambrose of Milan.

Now greatly influenced by Ambrose, he codifies the separation between East and West.

The Westerners, satisfied with the triumph of orthodoxy, bow to this policy.

Ambrose and Damasus, operating now with official state support, deal harshly with the Arians.

Paganism also is hounded: following Theodosius' lead, Gratian refuses the chief priesthood, removes the altar of Victory from the hall of the Roman Senate, and deprives the pagan priests and the Vestal Virgins of their subsidies and privileges.

The pagan senators are outraged, but their protests are futile because Gratian is watched over by Ambrose.

Gratian also publishes an edict that all their subjects should profess the faith of the bishops of Rome and Alexandria (i.e., the Nicene faith).

The move is mainly aimed at the various beliefs that had arisen out of Arianism, but smaller dissident sects, such as the Macedonians, are also prohibited.

Named after Bishop Macedonius of Constantinople, the Macedonian sect, regarded as heretical by the mainstream church, professes a belief similar to that of Arianism, denying the divinity of the Holy Spirit, and regarding the essence of Jesus Christ as being the same in kind as that of God the Father.

The sect's members are also known as pneumatomachians, the “spirit fighters.” The nature of the connection between the Macedonians and Bishop Macedonius is unclear; most scholars today believe that Macedonius had died (around 360) before the sect emerged.

Damasus, perhaps wary of the growing strength of Constantinople, which is already claiming to be the New Rome, calls a synod that officially pronounces Rome's primacy.

Jerome, having returned to Rome around this time, stays on to become Damasus' secretary, close adviser, and friend.

The Dingling, a Siberian people who originally lived on the bank of the Lena River in the area west of Lake Baikal, had begun to expand westward in the third century.

Some groups of Dingling also moved to China and settled there in the first century CE as early as during Wang Mang's reign, forming part of the southern Xiongnu tribes known as Chile during the third century, from which the later name Chile originated.

They adopted the last name Zhai.

The name "Chile" and "Gaoche" had first appeared in Chinese literature during the campaigns of Former Yan and Dai in 357 and 363 respectively.

However, the protagonists will be equally addressed as "Dingling" in the literary record of the Southern Dynasties.

Dingling leader Zhai Bin, who had rebelled against Former Qin's emperor Fu Jiān in 383, had supported Later Yan's founding emperor Murong Chui when Murong Chui rebelled against Former Qin as well and established Later Yan.

However, in 384, as Murong Chui is besieging the important city Yecheng, which is defended by Fu Jiān's son Fu Pi, Zhai Bin, seeing that Murong Chui is unable to capture the city quickly, begins to consider other options.

When, in particular, he requests a prime ministerial title from Murong Chui and is refused, Zhai Bin prepares to ally with Fu Pi instead, but his plan is discovered, and he is killed, along with his brothers Zhai Tan and Zhai Min.

It is apparently at this time that Zhai Bin’s son or nephew Zhai Liao and his cousin Zhai Zhen flee with some of their Dingling troops and resists Later Yan's subsequent campaigns to take the territory north of and around the Yellow River.

The strategically important city of Xiangyang, gateway to the Middle Yangtze, had fallen to Fu Jian in 379.

The controversial Murong Chui, a great general of the Chinese/Xianbei state Former Yan, had fled to Former Qin and become one of Fu Jian’s generals, participating in the campaign commanded by Fu Jian's son Fu Pi against Jin's key city of Xiangyang.

Fu Jian had conquered all of north China by 381 and began preparing for an invasion of the south.

In 382, when Fu Jian wanted to launch a major campaign to destroy Jin and unite China, most officials, including Fu Jian's brother Fu Rong, Duke of Yangping, who had succeeded Wang Meng as prime minister after Wang's death in 375, opposed, but Murong Chui and Yao Chang urged the campaign.

In May of 383, a Jin army of one hundred thousand commanded by Huan Chong attempts to recover Xiangyang but is driven off by a Qin relief column of fifty thousand men.

Fu Jian responds by ordering a general mobilization against Jin, conscripting one in ten able men and mustering thirty thousand elite guards.

In August, Fu Jian sends his brother Fu Rong with an advance force of three hundred thousand.

Later this month, Fu Jian marches with his army of two hundred and seventy thousand cavalry and six hundred thousand infantry from Chang'an, reaching Xiangcheng in September.

Separate columns are to push downstream from Sichuan, but the main offensive is to occur against the city of Shouchun on the Huai River.

Emperor Xiaowu of Jin, hurriedly preparing a defense, assigns Huan Chong responsibility for the defense of the Middle Yangtze.

To Xie Shi and Xie Xuan and the elite eighty thousand-strong Beifu Army is given the defense of the Huai River.

The Jin army’s overall military strategist, prime minister Xie An, lacks military abilities but calms the panicking officials and people by his example.

The Former Qin forces under Fu Rong capture the important Jin city of Shouyang (in modern Lu'an, Anhui) in October.

Fu Jiān, seeing a possibility of a quick victory, leaves his main force at Xiangcheng and leads eight thousand light cavalry to rendezvous with Fu Rong while dispatching the captured Jin official Zhu Xu as a messenger to try to persuade Xie Shi to surrender.

Instead, Zhu advises Xie Shi that fact the Former Qin force has not entirely assembled and that he should try to defeat the enemy’s advance forces.

Xie Xuan and Liu Laozhi, leading five thousand elite troops to engage the Former Qin advance force, scored an unexpected victory, killing fifteen thousand of the enemy troops.

In November, the Former Qin troops encamp west of the Fei River; the numerically inferior Jin forces halt east of the river, unable to advance.

Xie Xuan sends a messenger to Fu Rong, suggesting that the Former Qin forces retreat slightly west to allow Jin forces to cross the Fei River, so that the two armies can engage.

Most of Fu Jian’s generals oppose this plan, but Fu Jiān, planning to attack the Jin forces as they cross the river, overrules them.

Fu Rong agrees and orders a retreat but the Qin army, its morale low, panics when Zhu Xu manages to broadcast the false information that their retreating force has been defeated.

The retreat becomes a rout, and the generals Xie Xuan, Xie Yan, and Huan Yi cross the river to launch a major assault.

Fu Rong attempts to halt the retreat and reorganize his troops, but after becoming unhorsed, he is killed by Jin troops.

The Jin army continues their pursuit, and the entire Former Qin force collapses.

In the ensuing retreat, beset by famine and death from exposure and harried by the Jin army, the Former Qin force loses an estimated seventy to eighty percent of its strength.

The battle is considered one of the most significant in the history of China.

Almost the entire Former Qin army has collapsed, although the forces under Murong Chui's command remain intact, and Fu Jian, who had suffered an arrow wound during the defeat, has fled to Murong Chui.

Murong Chui's son Murong Bao and brother Murong De have both tried to persuade Murong Chui to kill Fu Jian while it is within his power to do so, but Murong Chui instead returns his forces to Fu Jian's command and returns to Luoyang with Fu Jian.

However, responding to a suggestion by his son Murong Nong, he plans a rebellion to rebuild the Yan state.

Murong Chui tells Fu Jian that he fears rebellion by the people of the Former Yan territory, and that it would be best if he were to lead a force to pacify the region.

Fu Jian agrees, despite opposition by Quan Yi, and Murong Chui leads the army to Yecheng, defended by Fu Pi.

They suspect each other, but neither ambushes the other.

When the Dingling chief Zhai Bin rebels and attacks Luoyang, defended by Fu Pi's younger brother Fu Hui, Fu Pi orders Murong Chui to put down Zhai's rebellion, and Fu Pi sends his assistant Fu Feilong to serve as Murong Chui's assistant.

On the way to Luoyang, however, Murong Chui kills Fu Feilong and his Di soldiers and prepares to openly rebel.

Meanwhile, despite his suspicions of Murong Chui, Fu Pi does not put under surveillance Murong Chui's son Murong Nong and nephews Murong Kai and Murong Shao, and the three flee from Yecheng and initiate a rebellion of their own.

Ulfilas, Arian bishop of the Goths, dies in 383, leaving a translation of the Bible into the Gothic language: it is the oldest surviving Germanic literary text.

The sources differ in how much they credit Ulfilas with the conversion of the Goths.

Socrates Scholasticus gives Ulfilas a minor role, and instead attributes the mass conversion to the Therving chieftain Fritigern, who had adopted Arianism out of gratitude for the military support of the Arian emperor Valens.

Sozomen attributes the mass conversion primarily to Ulfilas, though he also acknowledges the role of Fritigern.

Years: 381 - 381

Locations

People

Groups

- Korean people

- Silla, Kingdom of

- Goguryeo (Koguryo), Kingdom of

- Chinese (Han) people

- Chinese Empire, Tung (Eastern) Jin Dynasty