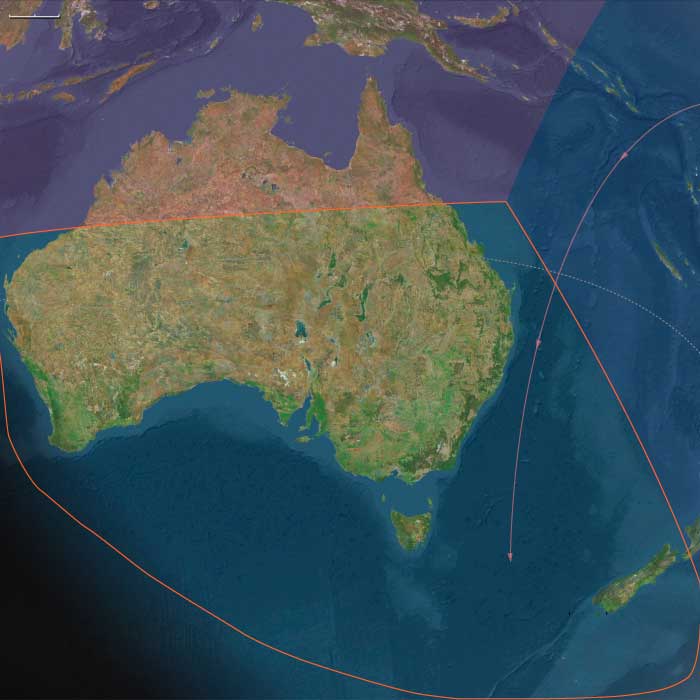

Proceeding south, Tasman skirts the southern end …

Years: 1642 - 1642

November

Proceeding south, Tasman skirts the southern end of Tasmania and turns northeast, now trying to work his two ships into Adventure Bay on the east coast of South Bruny Island where he is blown out to sea by a storm; this area he names Storm Bay.

Tasman anchors two days later to the North of Cape Frederick Hendrick just north of the Forestier Peninsula.

Locations

People

Groups

- Aotearoa

- Maori people

- Netherlands, United Provinces of the (Dutch Republic)

- Dutch East India Company in Indonesia

- Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC in Dutch, literally "United East Indies Company")

Topics

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 11 total

Alonzo Cano, a painter, architect and sculptor native to Granada, has been made first royal architect, painter to Philip IV, and instructor to the prince, Balthasar Charles, Prince of Asturias.

Atlantic Southwest Europe (1648–1659 CE): Consolidation, Conflict, and Regional Transformation

Between 1648 and 1659, Atlantic Southwest Europe—encompassing northern and central Portugal (including Lisbon), Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, northern León and Castile, northern Navarre, northern Rioja, and the Basque Country—experienced a decisive decade of political consolidation, economic stabilization, and intensified regional identities. Marked by Portugal’s successful defense of independence, adjustments in Spain following the Treaty of Westphalia, and reinforced regional autonomy in northern Spanish territories, this era established critical foundations for future stability, cultural flourishing, and distinct national identities.

Political and Military Developments

Portugal’s Successful Defense of Independence

Portugal effectively defended its newly regained independence (Portuguese Restoration War, 1640–1668) under King João IV (House of Braganza), significantly stabilizing political governance. Northern and central Portugal, particularly the strategic cities of Porto, Viana do Castelo, and the capital, Lisbon, fortified coastal defenses against Spanish incursions, ensuring continued maritime security and national sovereignty.

Impact of the Peace of Westphalia (1648) on Northern Spain

The Treaty of Westphalia (1648) concluded the devastating Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), compelling Spain to reassess and curtail its expansive European ambitions. Northern Spanish regions—Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, the Basque Country, northern León, and Castile—benefited from the reduced military burden, enabling economic stabilization and fostering a revival of local governance through reassertion of traditional fueros.

The Franco-Spanish Conflict and the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659)

Ongoing hostilities between Spain and France, culminating in the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659), significantly impacted northern Navarre and northern Rioja. Notably, border territories in northern Navarre were transferred to France, reshaping local political allegiances, trade networks, and cultural identities, reflecting enduring geopolitical shifts.

Economic Developments: Recovery and Realignment

Economic Stabilization in Northern Spanish Territories

Following decades of prolonged conflict, northern Spanish regions experienced gradual economic recovery. Agricultural revitalization, fishing industry improvements, and modest maritime trade resurgence notably benefited coastal cities such as Vigo, Santander, Bilbao, and San Sebastián. Enhanced commercial relations with England, the Dutch Republic, and France partially compensated for diminished Portuguese trade links post-1640.

Portuguese Maritime and Commercial Revival

Northern and central Portugal experienced sustained economic growth and maritime expansion. Stability under the Braganza monarchy facilitated renewed overseas trade and strengthened commercial connections, especially with England and the Dutch Republic. Porto thrived through increased export of its renowned port wine, while Lisbon reasserted itself as an essential hub for transatlantic commerce, significantly contributing to Portugal’s national prosperity.

Religious and Cultural Developments

Reinforced Counter-Reformation Orthodoxy

Counter-Reformation influence remained deeply entrenched across Atlantic Southwest Europe. Catholic orthodoxy was rigorously maintained through influential ecclesiastical institutions and active inquisitorial tribunals, notably in Valladolid, Pamplona, Braga, and Lisbon. Catholic education and doctrinal enforcement persisted, integrating religious orthodoxy with regional cultural traditions.

Flourishing of Regional Cultures and Identities

Despite rigid religious oversight, vibrant cultural expression flourished across the region. Galicia, Asturias, the Basque Country, and northern Portugal experienced notable growth in regional literature, music, folklore, and visual arts, expressing robust local identities. In central Portugal, the cultural atmosphere of Lisbon flourished under royal patronage, marked by distinctive Portuguese Baroque architecture, literary achievements, and artistic innovation, deeply reinforcing national pride and identity.

Social and Urban Developments

Urban Revival and Regional Prosperity

Northern Portuguese cities, notably Porto, Braga, and central Portugal’s Lisbon, benefited significantly from political stability, maritime commerce, and economic opportunities. Urban centers expanded, attracting rural migrants, bolstering merchant and artisan classes, and enhancing civic infrastructure and social stability. In northern Spanish regions, cities such as Bilbao, Santander, Santiago de Compostela, and Vigo likewise experienced urban revitalization, although more modest due to ongoing economic recovery.

Affirmation of Regional Autonomy and Fueros

In northern Spain, traditional regional privileges (fueros) in Galicia, the Basque territories, and northern Navarre were decisively reaffirmed, reinforcing local governance and economic independence from central authority. Local elites skillfully defended regional autonomy, resisting Madrid’s centralizing attempts, thereby preserving distinct governance structures and cultural identities amidst broader geopolitical pressures.

Persistent Rural Hardship and Demographic Shifts

While urban regions prospered, rural areas across Galicia, Asturias, northern León, and Castile continued experiencing economic hardships. Agricultural stagnation, demographic pressures, and fiscal demands perpetuated rural poverty, prompting significant internal migration to cities and overseas emigration to Portuguese and Spanish colonies in the Americas, reshaping demographic patterns.

Notable Regional Groups and Settlements

-

Portuguese (Northern and Central): Successfully consolidated independence, establishing strong governance, economic prosperity, and cultural vitality, notably in Porto, Braga, and Lisbon.

-

Galicians and Asturians: Benefited modestly from reduced warfare but continued struggling economically, preserving vibrant cultural traditions and regional autonomy.

-

Cantabrians and Northern Castilians: Experienced gradual economic stabilization and modest maritime revival but remained under fiscal strain from central authorities.

-

Basques and Navarrese: Strengthened regional autonomy and fueros significantly, successfully preserving local governance and cultural distinctiveness amid geopolitical shifts caused by the Treaty of the Pyrenees.

Long-Term Significance and Legacy

Between 1648 and 1659, Atlantic Southwest Europe:

-

Achieved decisive political consolidation and regional stability, notably through Portugal’s successful defense of independence and strengthened local governance across northern Spain.

-

Experienced significant economic recovery and maritime revival, particularly benefiting northern and central Portuguese cities, shaping future economic trajectories and prosperity.

-

Reinforced distinct regional identities, cultural expressions, and autonomy movements, influencing enduring patterns of governance, cultural resilience, and local heritage preservation.

-

Underwent notable geopolitical realignment due to the Treaty of the Pyrenees, reshaping political boundaries and alliances with lasting implications for regional identities and governance.

This critical decade firmly established the political, economic, and cultural foundations of modern Atlantic Southwest Europe, marking a definitive shift from prolonged conflict toward stability, prosperity, and enduring regional autonomy, significantly influencing the region’s subsequent historical development.

Atlantic West Europe (1648–1659): The Peace of Westphalia, Economic Recovery, and Cultural Renewal

From 1648 to 1659, Atlantic West Europe—comprising northern France, the Low Countries (modern-day Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg), and the Atlantic and Channel-facing regions—entered a critical era of political stabilization, economic recovery, and renewed cultural dynamism following the conclusion of the devastating Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). The Peace of Westphalia (1648) reshaped Europe's political landscape, securing Dutch independence, significantly altering Franco-Spanish relations, and influencing regional economic and cultural trajectories.

Political and Military Developments

The Peace of Westphalia (1648): New Political Order

-

The treaties signed at Münster and Osnabrück in 1648 ended the Thirty Years' War, dramatically reshaping Europe's political order:

-

The Dutch Republic gained full international recognition of its independence from Habsburg Spain, solidifying the northern provinces’ sovereignty and ending eight decades of conflict (Dutch Revolt, 1568–1648).

-

The Spanish Netherlands (modern Belgium and Luxembourg) remained under Habsburg control, but the war left these territories politically weakened, vulnerable, and economically diminished.

-

France: Consolidation under Cardinal Mazarin and Louis XIV

-

Under Cardinal Mazarin's regency for the young Louis XIV (1643–1715), France emerged as a dominant European power, successfully securing territorial gains along its eastern borders through the Peace of Westphalia.

-

The Fronde rebellion (1648–1653), a series of civil conflicts in France driven by noble opposition to Mazarin’s centralized policies and fiscal pressures, posed temporary challenges to royal authority. The ultimate suppression of the Fronde reinforced royal absolutism, paving the way for Louis XIV’s centralized monarchy.

Continued Franco-Spanish Conflict: Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659)

-

Despite Westphalia, France and Spain continued warfare until the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659) definitively ended hostilities:

-

France obtained significant territorial gains, including Roussillon and Artois, strengthening its geopolitical position.

-

The treaty, cemented by Louis XIV’s marriage to Maria Theresa of Spain, signaled Spain’s diminished European influence and French ascendancy.

-

Economic Developments: Stabilization and Maritime Revival

Dutch Economic Prosperity and Maritime Dominance

-

With independence secure, the Dutch Republic entered its commercial Golden Age, with Amsterdam cementing its status as Europe’s premier financial, trade, and shipping center.

-

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) and West India Company (WIC) expanded global trade networks, enhancing economic prosperity and reinforcing the Netherlands' maritime hegemony.

Northern France: Post-war Economic Recovery

-

Northern French ports—Bordeaux, Nantes, Rouen—rapidly recovered and expanded maritime trade, notably wine exports from Bordeaux, textiles from Rouen, and colonial products from Nantes, enhancing economic prosperity after decades of warfare.

-

Agricultural productivity gradually rebounded, though rural regions experienced slower recovery due to persistent demographic and infrastructural damage from warfare and taxation.

Spanish Netherlands: Economic Struggles and Limited Recovery

-

The southern Low Countries (modern Belgium and Luxembourg) experienced more significant economic hardship post-war due to sustained military occupations, disrupted trade routes, and continued vulnerability to conflict between France and Spain.

-

Cities like Antwerp saw diminished trade prominence compared to Amsterdam, marking an economic shift toward the northern provinces.

Religious and Intellectual Developments

Religious Stability and Consolidation

-

The Peace of Westphalia solidified the principle of territorial religious sovereignty, stabilizing religious divisions but leaving profound Protestant–Catholic divides intact, especially visible between the Calvinist Dutch Republic and Catholic Spanish Netherlands.

-

France continued promoting Catholic orthodoxy while cautiously maintaining internal peace through limited religious tolerance for Huguenots.

Intellectual Flourishing and Scientific Advancement

-

Intellectual activity thrived, particularly in the Dutch Republic and France. René Descartes’ philosophical and scientific ideas continued influencing intellectual circles significantly.

-

Scientific communities in Amsterdam, Leiden, and Paris flourished, fostering early Enlightenment thinking and advancing research in medicine, astronomy, mathematics, and natural philosophy.

Cultural and Artistic Developments

Dutch Golden Age of Painting

-

The post-war Dutch Republic experienced unmatched artistic prosperity, led by artists such as Rembrandt van Rijn, whose mature masterpieces reflected deep psychological insight and remarkable realism, alongside figures like Johannes Vermeer, who began his career in this period.

-

Genre painting, landscapes, still lifes, and portraits became emblematic of Dutch cultural identity, reflecting urban prosperity, mercantile values, and Protestant cultural norms.

French Baroque and Courtly Culture

-

French artistic patronage flourished under Louis XIV’s court, initiating grand architectural projects and gardens at Versailles (begun 1660s), foreshadowing Louis XIV’s later cultural grandeur.

-

Literature and drama thrived, exemplified by playwrights like Pierre Corneille and Jean Racine, whose works established classical standards defining French literary excellence.

Social and Urban Developments

Urban Expansion and Commercial Growth

-

Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Antwerp, Brussels, and northern French port cities experienced significant urban expansion and infrastructural improvements, reflecting increased commercial prosperity.

-

Growing merchant classes wielded substantial influence, fostering social mobility and economic innovation, notably in the Dutch Republic and prosperous French cities.

Rural Recovery and Persistent Social Strains

-

Rural northern France and the southern Netherlands struggled with slower economic recovery, demographic stagnation, and persistent poverty due to long-term wartime devastation, taxation, and agricultural difficulties.

-

Regional disparities intensified, accentuating economic contrasts between prosperous coastal urban centers and struggling rural hinterlands.

Legacy and Historical Significance

The years 1648–1659 marked a decisive transitional era in Atlantic West Europe:

-

Politically, the Peace of Westphalia and Treaty of the Pyrenees reshaped territorial boundaries, cemented Dutch independence, and solidified France’s ascendancy, profoundly influencing European power dynamics.

-

Economically, maritime revival, especially Dutch global trade and French port prosperity, established enduring economic trajectories that shaped early modern European economic leadership.

-

Culturally and intellectually, artistic and scientific achievements during this period left lasting cultural legacies, contributing significantly to European intellectual heritage and Baroque artistic expressions.

By 1659, Atlantic West Europe had substantially overcome wartime challenges, achieving political stabilization, economic revival, and cultural flourishing that established essential foundations for future growth, cultural influence, and geopolitical prominence in European and global contexts.

...Münster, in present-day Germany.

Despite not formally being recognized as an independent state, the Dutch republic has been allowed to participate in the peace talks; even Spain did not oppose this.

Eight Dutch representatives (two from Holland and one from each of the other six provinces) had arrived in Münster in January 1646 to start the negotiations.

The Spanish envoys had been given great authority by the Spanish King Philip IV who had been suing for peace for years.

The parties reach an agreement on January 30, 1648, and send a text to The Hague and Madrid to be signed.

Spain’s Renewed Effort Against Portugal and the Strain of War (1650s)

By the 1650s, Spain was once again preparing to direct its military efforts against Portugal, having secured peace in Europe with the Treaty of Westphalia (1648) and ended the Reapers’ War in Catalonia (1652). However, despite its ambitions to reclaim Portugal, Spain faced severe limitations in manpower, resources, and effective military leadership.

The Financial and Military Burden on Spain

- The war against Portugal was proving exceptionally costly:

- Between 1649 and 1654, over six million ducats—about 29% of Spain’s total defense spending—was directed toward fighting Portugal.

- By the 1650s, Spain maintained over 20,000 troops in Extremadura alone, nearly matching the 27,000 troops stationed in Flanders, a region that had long been Spain’s military priority.

- Despite these efforts, Spain struggled with:

- Recruitment shortages—its armies were spread too thin.

- Economic hardship—Spain’s declining control over trade weakened its ability to sustain prolonged warfare.

- Ineffective leadership—many of Spain’s most competent commanders were no longer available, forcing the reliance on less experienced generals.

Portugal’s Financial and Military Advantages

While Spain struggled, Portugal was able to sustain its war effort, largely due to:

-

Revenue from Colonial Trade

- Taxation of the spice trade from Asia and sugar exports from Brazil provided Portugal with a stable wartime income.

-

Support from Spain’s European Rivals

- Portugal benefited from assistance from Holland, France, and England, all of whom sought to weaken Spanish power.

- The Dutch provided naval support to defend Portugal’s overseas empire, particularly in Brazil and Africa.

- French and English backing helped maintain Portugal’s land defenses in Europe.

Conclusion: Spain’s Overextension and Portugal’s Growing Strength

By the 1650s, Spain’s inability to effectively suppress Portugal became increasingly clear. The war drained Spanish resources, while Portugal, backed by its trade revenues and foreign alliances, remained resilient. The cost of reconquering Portugal ultimately proved too high for Spain, paving the way for Portugal’s final victory and the official recognition of its independence in 1668.

The great French Marshal Turenne commands the combined Anglo-French army for the invasion of Flanders.

The Spanish Army of Flanders is commanded by Don Juan-José, an illegitimate son of the Spanish King Philip IV.

The Spanish army of fifteen thousand troops is augmented by a force of 3,000 English Royalists, formed as the nucleus of potential army for the invasion of England by Charles II, with Charles's brother James, Duke of York, among its commanders.

The Commonwealth fleet is blockading Flemish ports but to Cromwell's annoyance the military campaign had started late in the year and has been subject to many delays.

Turenne, having spent the summer of 1657 campaigning against the Spanish in Luxembourg, makes no move to attack Flanders until September.

Mardyck is captured on September 9 and garrisoned by Commonwealth troops.

Twenty-four years of Franco–Spanish warfare formally end with the Treaty of the Pyrenees, signed on November 7, 1659 on Pheasant Island, a river island on the border between the two countries.

French King Louis XIV and King Philip IV of Spain agree to French acquisition of the County of Roussillon, the northern half of the county of Cerdanya (thereby splitting the Catalan population between the two countries), and most of Artois.

The Treaty of the Pyrenees is considered part of the Peace of Westphalia, with which end the European wars of religion.

Atlantic Southwest Europe (1660–1671 CE): Stability, Economic Renewal, and Cultural Flourishing

Between 1660 and 1671, Atlantic Southwest Europe—encompassing northern and central Portugal (including Lisbon), Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, northern León and Castile, northern Navarre, northern Rioja, and the Basque Country—entered a transformative period of relative peace, economic revitalization, and notable cultural advancement. Following the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659) and the firm establishment of Portuguese independence, the region experienced internal consolidation, renewed commercial growth, and intensified cultural expressions rooted in regional identities and Baroque aesthetics.

Political and Military Developments

Portugal’s Political Stabilization under Afonso VI and Pedro II

Under King Afonso VI (1656–1667) and subsequently his brother, regent (and later King) Pedro II, Portugal secured political stability and diplomatic recognition, successfully preserving independence following decades of Spanish threats. Northern and central Portugal—particularly the influential cities of Lisbon, Porto, and Viana do Castelo—benefited significantly from this stable environment, reinforcing local governance structures and promoting economic prosperity.

Spanish Consolidation and Regional Autonomy

Following the Treaty of the Pyrenees, the Spanish monarchy under Philip IV (until 1665) and Charles II (from 1665)turned toward internal stabilization, allowing northern Spanish regions greater regional autonomy within a royal framework. Territories such as Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, the Basque provinces, northern Navarre, and northern Rioja reaffirmed their treasured fueros (traditional privileges), enabling stronger local governance and fostering political stability.

Reduced Military and Fiscal Pressures

The cessation of prolonged international conflicts after 1659 notably diminished military and fiscal burdens on northern Spanish territories. Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, and the Basque provinces benefited from reduced taxation and fewer conscription demands, facilitating economic recovery, social stability, and improved relations with central authority.

Economic Developments: Maritime Prosperity and Industrial Revival

Portuguese Maritime and Commercial Expansion

Portugal experienced marked economic revival, particularly through flourishing maritime commerce in the Atlantic. Lisbon thrived as an essential commercial and imperial hub, while Porto consolidated its status as a leading exporter of port wine, significantly bolstered by strengthened trading partnerships with Britain. Northern ports such as Viana do Castelo likewise prospered through shipbuilding and transatlantic commerce.

Revival of Northern Spanish Maritime Trade

Northern Spanish coastal cities, including Vigo, Santander, and Bilbao, saw renewed maritime prosperity through enhanced trading relationships with England, France, and the Netherlands. Improved security in Atlantic waters facilitated growth in fisheries, shipbuilding, and regional trade networks, contributing to economic stability.

Strengthening Local Industries

In northern Spain, regional industries—particularly shipbuilding, wool production, fishing, and iron manufacturing—experienced renewed vitality, notably in the Basque Country. This industrial revival bolstered regional economic independence and lessened reliance on Madrid, further solidifying local autonomy and prosperity.

Religious and Cultural Developments

Sustained Counter-Reformation Influence

Throughout Atlantic Southwest Europe, the Counter-Reformation retained considerable cultural and social influence. Catholic orthodoxy, reinforced by monastic institutions, universities, and inquisitorial tribunals, continued to shape local religious and intellectual life, particularly prominent in Lisbon, Braga, Valladolid, and Pamplona.

Regional Cultural Flourishing and Baroque Influence

Cultural activities surged across the region, notably reflecting Baroque artistic and architectural ideals. In northern and central Portugal, significant architectural projects flourished in Lisbon, Porto, and Braga, symbolizing national pride and renewed confidence in Portuguese identity. Literary, poetic, and musical expressions flourished, reinforcing distinct Portuguese cultural heritage.

In northern Spain, similar cultural flourishing occurred, with Baroque architecture prominently featured in cathedrals and public buildings in Santiago de Compostela, Burgos, and Santander. Galician, Basque, and Navarrese traditions were celebrated, reinforcing regional identity alongside broader Iberian cultural currents.

Social and Urban Developments

Urban Expansion and Enhanced Social Mobility

Major urban centers—Lisbon, Porto, Bilbao, Santander, and Santiago de Compostela—experienced significant population growth, driven by rural-to-urban migration and increased commercial activity. Merchant and artisan classes expanded notably, promoting greater social mobility and reshaping urban landscapes with improved infrastructure and vibrant civic life.

Reinforced Regional Identities and Autonomy

Across northern Spain, traditional fueros empowered local authorities in Galicia, the Basque provinces, and northern Navarre. Regional governance thrived, balancing loyalty to central monarchy with local interests and cultural distinctiveness. These strengthened regional identities laid enduring foundations for local governance and future autonomy movements.

Persistent Rural Challenges

While urban centers prospered, rural regions in Galicia, Asturias, and northern León continued experiencing hardships. Persistent agricultural stagnation, taxation pressures, and demographic changes prompted rural populations to migrate to burgeoning urban centers or emigrate to overseas colonies in the Americas, reshaping demographic structures.

Notable Regional Groups and Settlements

-

Portuguese (Northern and Central): Benefited from political stability, maritime prosperity, and cultural flourishing, particularly in Lisbon, Porto, and Braga.

-

Galicians and Asturians: Enjoyed modest economic recovery but continued facing rural challenges, maintaining strong cultural traditions.

-

Cantabrians and Northern Castilians: Experienced economic revitalization through maritime trade and local industries but remained cautious of central authority.

-

Basques and Navarrese: Successfully reinforced local autonomy, vigorously defending fueros and regional governance structures, ensuring long-term cultural and political resilience.

Long-Term Significance and Legacy

Between 1660 and 1671, Atlantic Southwest Europe:

-

Achieved crucial political stability, allowing economic revitalization and regional consolidation after prolonged warfare.

-

Experienced notable maritime prosperity, particularly in central and northern Portuguese cities, laying critical foundations for sustained economic growth.

-

Intensified cultural expressions, significantly shaped by the Baroque aesthetic, profoundly reinforcing national and regional identities.

-

Strengthened regional autonomy through renewed affirmation of fueros, deeply influencing the region’s governance structures and long-term political stability.

This era marked a decisive shift toward internal prosperity, cultural vitality, and regional autonomy in Atlantic Southwest Europe, significantly shaping the region’s historical trajectory and laying enduring foundations for future developments.

A peace treaty between France and Spain is consummated in 1660 by the marriage of Louis XIV with Maria Theresa, the daughter of Philip IV, King of Spain and Elizabeth of France.

The ceremony takes place on the Island of Pheasants, a small swampy island in the Bidassoa on the riverine border of France and Spain.

The renowned painter Diego Velázquez, charged with the decoration of the Spanish pavilion and with the entire scenic display, attracts much attention from the nobility of his bearing and the splendor of his costume.

He had returned to Madrid on June 26, and on July 31 he had been stricken with fever.

Feeling his end approaching, he signs his will, appointing as his sole executors his wife and his firm friend named Fuensalida, keeper of the royal records.

He dies on August 6, 1660, at sixty-one.

The Portuguese Restoration War (1640–1668) and the Battle of Ameixial (1663)

The Portuguese Restoration War (1640–1668), originally called the Acclamation War, was a prolonged conflict between Portugal and Spain following the Portuguese revolution of 1640, which ended the dual monarchy of the Iberian Union (1580–1640). Although it included sporadic skirmishes and larger battles, Spain made a major effort to crush Portuguese independence in the early 1660s, culminating in the Spanish defeat at the Battle of Ameixial in 1663.

Spain’s Renewed Offensive: The Capture of Évora (1662–1663)

- By 1662, Spain was determined to end the Portuguese rebellion and restore Habsburg control.

- John of Austria the Younger, Philip IV’s illegitimate son, led 14,000 Spanish troops into Alentejo, Portugal’s vulnerable southeastern frontier region.

- In May 1663, the Spanish captured Évora, one of the most important cities in Alentejo, opening the possibility of a march on Lisbon, only 135 kilometers away.

- However, logistical failures—lack of ammunition, food, and money—crippled the Spanish advance, preventing them from consolidating their position.

The Battle of Ameixial (June 8, 1663): The Turning Point

Portugal, recognizing the seriousness of the Spanish invasion, mobilized a large relief army:

- António Luís de Meneses, 1st Marquess of Marialva, took command of 20,000 Portuguese troops.

- The army included foreign officers, notably the Huguenot general Friedrich Hermann von Schönberg (Duke of Schomberg), who brought military expertise from European conflicts.

- Portugal was reinforced by English troops, part of the Anglo-Portuguese alliance.

The Battle Near Santa Vitória do Ameixial (June 8, 1663)

- The Portuguese and English forces attacked Spanish positions near the village of Santa Vitória do Ameixial.

- After intense fighting, the Spanish were decisively defeated, suffering heavy casualties.

- The defeat forced John of Austria to abandon Évora, retreating to Badajoz in Extremadura.

Spanish Collapse and the Recapture of Évora (June 24, 1663)

- The Spanish garrison of Évora, consisting of 3,700 men, surrendered on June 24, 1663.

- This completed the failure of the Spanish expedition, which had begun with high hopes but ended in retreat and humiliation.

Conclusion: The Beginning of Spain’s Decline in the War

The Battle of Ameixial (1663) was a decisive victory for Portugal, demonstrating its resilience and military capability against Spain.

- The Spanish defeat crippled their ability to retake Portugal, shifting the momentum of the war.

- Portugal’s alliance with England and use of foreign commanders (like Schomberg) strengthened its military leadership.

- By 1668, after further defeats, Spain formally recognized Portugal’s independence with the Treaty of Lisbon.

The Portuguese Restoration War, though long and costly, ultimately secured Portugal’s independence from Spain, ensuring the continuation of the Braganza dynasty and reinforcing Portugal’s separate national identity.

Years: 1642 - 1642

November

Locations

People

Groups

- Aotearoa

- Maori people

- Netherlands, United Provinces of the (Dutch Republic)

- Dutch East India Company in Indonesia

- Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC in Dutch, literally "United East Indies Company")