Shi Huangdi dies prematurely in 210 BCE, …

Years: 210BCE - 210BCE

Shi Huangdi dies prematurely in 210 BCE, leaving control in the hands of his son Zhao Huha, a weak heir incapable of dealing with the problems he faces.

Strife erupts immediately.

Locations

People

Groups

Topics

Commodoties

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 63612 total

Shi Huangdi is buried at a grave complex in Xi'an in Shaanxi province with a magnificent treasure of approximately six thousand life-sized terra cotta soldiers, servants and horses.

The vast ceramic army is grouped in battle formation—some mounted on horse-drawn chariots, others foot soldiers armed with elaborately crafted bronze spears and swords and crossbows.

It is surprising that the metal trappings of the spears, swords, halberds, and crossbows, are all of bronze, in that China has reportedly been using iron for some hundreds of years, but bronze is the standard metal for weaponry (and will remain so until the first century CE).

The realistic features of many of the warriors, conveyed with remarkable simplicity, reflect the minority peoples incorporated into the Qin empire.

Arsinoe, the wife and sister of Ptolemy IV Philopater, ruler of the Hellenistic kingdom of Egypt, in 210 bears him a successor.

Ptolemy maintains peaceful relations with the neighboring kingdom to the south.

He retains a number of islands in the Aegean, but has refused to become embroiled in the wars of the Greek states, in spite of honors granted him.

He has avoided involvement in local struggles in Syria also, despite the attempts of his corrupt minister Sosibius to embroil Egypt there. (Polybius, the Greek historian, credits Ptolemy's debauched and corrupt character, rather than his diplomatic acumen, in having kept him clear of foreign entanglements.)

Marcellus had resigned from command of the Sicilian province at the end of 211 BCE, thereby putting the praetor of the region, M. Cornelius, in charge.

Upon his return to Rome, Marcellus had not received the triumphal honors that would be expected for such a feat, as his political enemies objected that he had not fully eradicated the threats in Sicily.

Akragas, which has suffered badly during the two Punic Wars, with both Rome and Carthage fighting to control it, eventually falls in 210 to the Romans, who rename it Agrigentum, although it will remain a largely Greek-speaking community for centuries hereafter.

Tauromenium, present Taormina, had undoubtedly continued to form a part of the kingdom of Syracuse until the death of Hieron, and only passes under the government of Rome when the whole island of Sicily is reduced to a Roman province.

However, we have scarcely any account of the part it took during the Second Punic War, though it would appear, from a hint in Appian, that it submitted to Marcellus on favorable terms; and it is probable that it is on this occasion it obtained the peculiarly favored position it is to enjoy under the Roman dominion.

We learn from Cicero that Tauromenium was one of the three cities in Sicily that enjoyed the privileges of a civitas foederata or allied city, thus retaining a nominal independence, and was not even subject, like Messana, to the obligation of furnishing ships of war when called upon.

All of Hispania south of the Ebro river is under Carthaginian control in 210 BCE, the year of Scipio's arrival.

Hannibal's brothers Hasdrubal and Mago, and Hasdrubal Gisco, are the generals of the Carthaginian forces in Hispania, and Rome is aided by the inability of these three figures to act in concert.

The Carthaginians are also preoccupied with revolts in Africa.

Soldiers Chen Sheng, Wu Guang, and others seize the opportunity to revolt against the Qin government in 209 BCE.

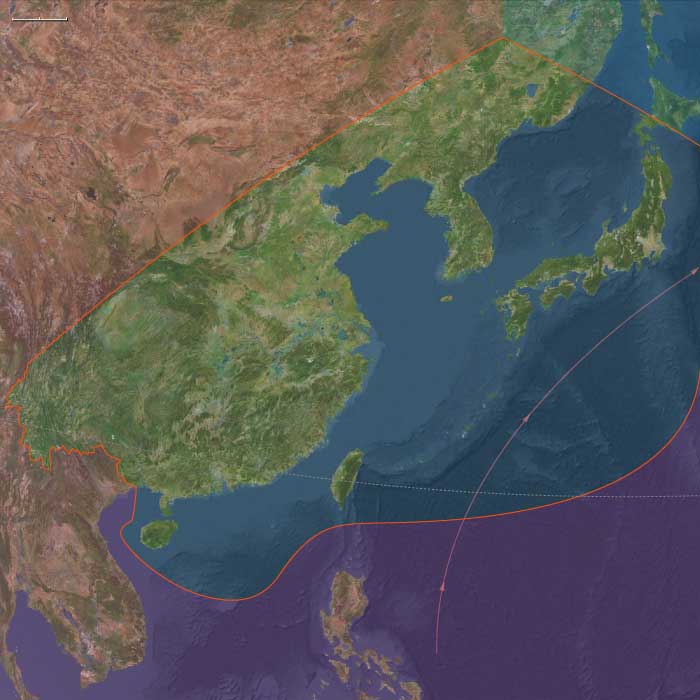

Insurrections spread throughout much of China (including those led by Xiang Yu and Liu Bang, who will later face off over the founding of the next dynasty) and the entire Yellow River region devolves into chaos.

Antiochus having entered upon the eastward campaign (212-205) for which he will gain renown, now attacks Artabanus.

The Parthians may in fact be hostile to the local Greek populations: during the initial phase of the war, they massacre all the Greek inhabitants of the city of Syrinx in Hyrcania.

Antiochus takes Syrinx and Hecatompylos, the Arsacid capital (the present location of which is uncertain), then crosses the mountains separating that province from Parthia, which he occupies.

Artabanus flees and takes refuge with the friendly Apasiacae, as had his father, Arsaces I.

The conflict between the Seleucids and Parthia, however, is ended by a compromise, just as it had been at the time of the invasion of Seleucus II.

A much more important struggle against the Bactrian kingdom of Euthydemus awaits Antiochus.

Preferred to make peace with Artabanus, he accords him the title of king in exchange for recognition of his fealty, and obliges the Parthian to send troops to reinforce the Syrian army.

This safeguards the rear of the Seleucid king, but the Macedonians have definitively lost the two provinces held by Artabanus.

Antiochus III, an ambitious Seleucid king who has a vision of reuniting Alexander the Great's empire under the Seleucid dynasty, launches a campaign in 209 BCE o regain control of the eastern provinces, and after defeating the Parthians in battle, he successfully regains control over the region.

The Parthians are forced to accept vassal status and now only control the land conforming to the former Seleucid province of Parthia.

However, Parthia's vassalage is only nominal at best and only because the Seleucid army is on their doorstep.

For his retaking of the eastern provinces and establishing the Seleuicd borders as far east as they had been under Seleucus I Nicator, Antiochus is awarded the title great by his nobles.

Luckily for the Parthians, the Seleucid Empire has many enemies, and it will not be long before Antiochus leads his forces west to fight Ptolemaic Egypt and the rising Roman Republic.

One Philopoemen, for some ten years a mercenary leader in Crete and now in his late fifties, had been trained to his career of arms by the Academic philosophers Ecdelus and Demophanes.

Elected federal cavalry commander for 210/209 on his return to Achaea, his reorganized troops defeat the Aetolians on the Elean frontier.

Tarantum supports Hannibal’s war against Rome, but in 209 BCE, the commander of a Bruttian force betrays the city to the Romans.

Indiscriminate slaughter ensues and among the victims are the Bruttians who had betrayed the city.

Afterwards thirty thousand of the Greek inhabitants are sold as slaves.

Tarentum's art treasures, including the statue of Nikè (Victory) are carried off to Rome.

Fabius Maximus had had the command in Campania in 211 BCE, during the year of his fourth consulship, and admitted the young soldier Marcus Porcius Cato, who had served at Capua, to the honor of intimate friendship.

At the siege of Tarentum, Cato, later to be known as Cato the Elder to distinguish him from his great-grandson, Cato the Younger, is again at the side of Fabius.