Melanesia

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 3 events out of 3 total

Melanesia (820 – 963 CE): Island Chiefdoms, Men’s Houses, and Canoe Worlds

Geographic and Environmental Context

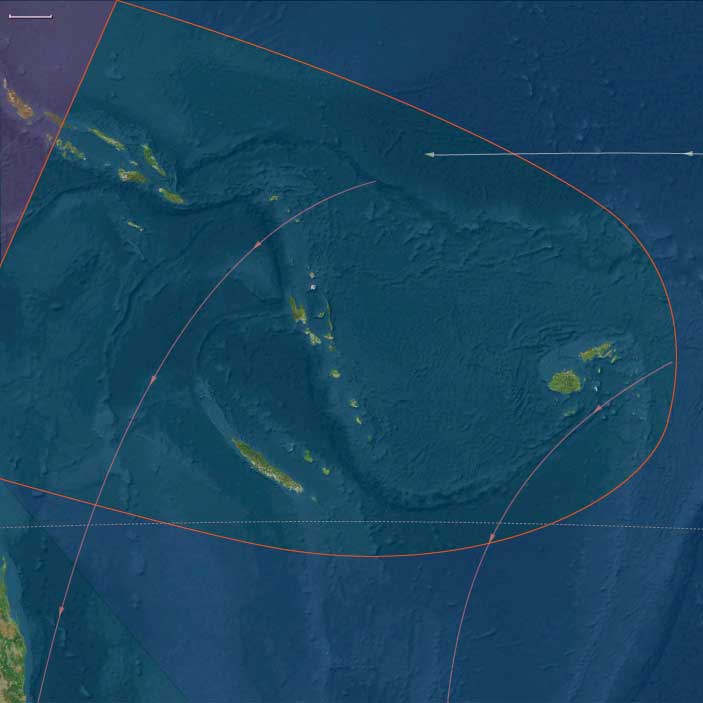

Melanesia during the Upper Late Medieval Age stretched from the Bismarck Archipelago and New Guinea in the west to Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia, and the Solomon Islands in the east.

A geography of volcanic highlands, deep valleys, limestone ridges, and reef-fringed coasts shaped societies into countless island and riverine polities joined by canoe corridors.

-

West Melanesia: New Guinea, Bougainville, and the Bismarck Archipelago—a dense mosaic of mountains, lowland swamps, and coastal lagoons.

-

East Melanesia: Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia, and the Solomons (excluding Bougainville)—fertile high islands bounded by lagoon and atoll margins.

Together they formed a world of gardens, pigs, and voyaging, where ritual, exchange, and landscape were inseparable.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

A warm, maritime regime prevailed.

-

Orographic rainfall on high islands sustained lush taro and yam terraces.

-

Cyclones periodically ravaged outer islands but fertile soils and strong exchange networks ensured recovery.

-

The approach to the Medieval Warm Period lengthened growing seasons and stabilized sea levels.

-

El Niño–Southern Oscillation swings caused occasional droughts, met by diversified cropping and storage.

Across the region, people adapted through mobility, multi-ecosystem subsistence, and ritual redistribution.

Societies and Political Developments

Highlands and River Basins (West Melanesia)

In the Wahgi, Asaro, Simbu, and Enga valleys of New Guinea, populous villages of clans and sub-clans thrived under big-man systems.

-

Authority was achieved, not inherited: leaders mobilized labor for gardens, pig feasts, and compensation exchanges.

-

Ridge-top palisades appeared in competitive zones.

-

In the Sepik and Ramu basins, men’s houses (haus tambaran) became political and ritual centers, their painted façades and carved spirit boards narrating clan origins.

-

Along the Papuan Gulf, stilt-house villages traded sago, shells, and ornaments through broad estuarine networks, early precursors to later Hiri-type voyages.

Islands and Coasts (East Melanesia)

Across Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia, and the Solomon Islands, ranked chiefdoms and grade-taking societiesstructured power.

-

In Vanuatu, the nimangki and sukwe systems advanced men through ritual pig payments; influence depended on wealth redistribution and feasting.

-

In Fiji, river-delta and coastal chiefdoms on Viti Levu and Vanua Levu coordinated irrigation, fishing, and craft production; inland settlements fortified ridges.

-

The Solomons combined coastal fishing hamlets and interior garden hamlets linked by ritual houses and marriage exchange.

-

New Caledonia’s upland communities cultivated yams and taro in ridged gardens under senior-lineage direction.

Economy and Trade

Agriculture formed the base everywhere, complemented by fishing and exchange.

-

Staples: yams, taro, bananas, breadfruit; in wetter valleys, irrigated taro pondfields; in dry pockets, giant swamp taro.

-

Livestock: pigs were the prime wealth animal—sacrificed in grade rituals, bridewealth, and compensation.

-

Fishing: lagoons and reefs supplied fish and shellfish; smoked and dried fish moved inland.

-

Inter-island trade: outrigger canoes carried shell rings, adze stone, fine mats, red feathers, cured pork, and salt.

-

West Melanesia: obsidian from Talasea (New Britain) and shell valuables from the Bismarcks reached far-flung coasts; sago, salt, and forest goods moved inland.

-

East Melanesia: shells, mats, and feather ornaments circulated among ritual partners; eastern Fiji and Tonga–Samoa acted as a cultural interface transmitting canoe forms and symbols of rank.

Exchange sustained both survival and prestige, binding hundreds of polities into a single economic sea.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Gardens: stone alignments, drainage ditches, and mulching stabilized soils; tree-crop management of pandanus and breadfruit supplemented root crops.

-

Animal management: pigs and chickens domesticated; dogs occasional companions.

-

Canoe technology: single and double outriggers, sewn planks, crab-claw or spritsails; expert navigation of reef passes and monsoon winds.

-

Pottery and tools: local ceramic traditions lingered in coastal Fiji and Vanuatu; stone adzes and shell tools dominated woodworking and canoe building.

-

Art and architecture: men’s houses and ritual platforms displayed clan emblems, drums, and conch trumpets, giving architecture a ceremonial voice.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Highland–coastal exchanges: salt, feathers, and pigs for shells and sago.

-

Bismarck Sea and Vitiaz Strait: central arteries connecting New Britain, New Ireland, Manus, and north New Guinea.

-

Vanuatu–Fiji–Solomons sailing lanes maintained ceremonial circuits of grade promotions and feasts.

-

Bougainville–Buka linked the Solomons to the Bismarck networks.

-

Seasonal wind calendars and ritual voyaging ensured constant circulation of people, stories, and valuables.

Belief and Symbolism

Across Melanesia, mana (spiritual potency) infused land, pigs, and shells; tabu rules guarded sacred places and resources.

-

Men’s houses stored ancestral skulls, masks, and sacred boards.

-

Pig tusks, shell rings, and red feathers symbolized wealth, power, and the fertility of exchange.

-

Feasts and grade ceremonies enacted cosmological balance, transforming surplus into alliance.

-

Artistic expression—carving, painting, dance, and drumming—synchronized ritual and politics, affirming kinship with ancestors and landscape.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Ecological diversification: gardens, reefs, forests, and sago swamps ensured multi-resource security.

-

Ritual redistribution: feasts and compensations reallocated food and valuables to buffer shocks.

-

Defensive mobility: paired coastal and ridge settlements provided refuge in conflict or cyclone.

-

Trade redundancy: overlapping exchange circuits kept essential goods moving after local crises.

These mechanisms maintained demographic and cultural stability through centuries of environmental fluctuation.

Long-Term Significance

By 963 CE, Melanesia was a region of dense, self-sustaining complexity:

-

West Melanesia’s big-man polities and men’s houses governed through feast, art, and alliance.

-

East Melanesia’s grade societies and chiefdoms converted horticultural surplus and pig wealth into structured hierarchy.

-

Canoe exchange networks across the Bismarck, Solomons, Vanuatu, and Fiji formed the connective tissue of Oceanic civilization.

These enduring institutions—ritual economies, engineered gardens, and sea-lanes—would underpin the fortified hill settlements, elaborate exchange spheres, and deepened inter-island alliances of the next age.

East Melanesia (820 – 963 CE): Island Chiefdoms, Grade Societies, and Canoe Exchange

Geographic and Environmental Context

East Melanesia includes Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia, and the Solomon Islands (excluding Bougainville, which belongs to West Melanesia).

-

High volcanic islands (Espiritu Santo, Efate, Tanna, Guadalcanal, Malaita, Viti Levu, Vanua Levu) provided fertile uplands, deep valleys, and fringing reefs.

-

Raised limestone islands and low atolls (e.g., parts of New Caledonia and the outer Solomons) offered narrower soils but rich lagoons.

-

Narrow coastal shelves, steep interior ridges, and reef passes segmented communities into clustered polities linked by canoe routes.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

A warm, maritime regime prevailed; the approach to the Medieval Warm Period brought slightly longer growing seasons.

-

Cyclones and drought pulses periodically stressed outer-island gardens and reef fisheries, but high-island watersheds buffered shortages.

-

Orographic rainfall on windward slopes sustained taro terraces and irrigated valley gardens.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Vanuatu: Island polities organized around grade-taking societies (e.g., nimangki, sukwe), where men advanced through ritual payments—especially pig tusks—to gain prestige and ritual authority. Leadership was competitive and distributed, but influential ritual specialists and “big-men” coordinated feasts, land, and conflict mediation.

-

Fiji: Coastal and riverine chiefdoms crystallized along fertile deltas of Viti Levu and Vanua Levu; inland, defensible ridge settlements emerged on spurs above garden lands. Kin-based councils managed irrigation ditches, fishing rights, and craft labor; alliances were sealed by marriage, exchange, and ceremonial hospitality.

-

Solomon Islands (except Bougainville): Clan-based chiefdoms on Guadalcanal, Malaita, Makira, and Isabel balanced coastal fishing villages with interior garden hamlets. Ritual houses anchored political life; dispute-settlement and compensation payments stabilized inter-lineage relations.

-

New Caledonia: Upland horticultural communities (later Kanak heartlands) cultivated yam and taro in ridged garden systems; authority resided in senior lineages that organized seasonal labor and ritual.

Economy and Trade

-

Horticulture: yams, taro, bananas, and breadfruit formed the staple base; giant swamp taro and taro terraces supported valley populations; pigs were critical wealth and feast animals.

-

Reef and lagoon fisheries: nearshore netting, line fishing, and shellfish collecting yielded steady protein; smoked and dried fish traveled as exchange goods.

-

Exchange networks: inter-island canoe voyages moved shell valuables, fine mats, adze stone, sennit cordage, red-feather ornaments, and cured pork. High islands funneled stone and forest products to atolls; atolls returned salt fish, coconut cordage, and shell.

-

Cross-cultural corridors: eastern Fiji interfaced with Tonga–Samoa to the east, while northern Vanuatu–Solomons touched the Micronesian periphery, transmitting canoe forms, ornaments, and ritual motifs.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Garden engineering: stone alignments and, in favored valleys, irrigated taro pondfields stabilized yields; mulching, mounding, and fallow rotations preserved soil fertility.

-

Animal management: pigs were fattened for grade rituals and compensation payments; chickens supplemented diets.

-

Canoe technology: outrigger sailing canoes (single and double) with crab-claw or spritsails crossed windward channels; shell and bone tools aided hull shaping; breadfruit and sennit lashings bound planks.

-

Ceramics: post-Lapita ceramic traditions persisted differentially (e.g., in parts of Fiji and Vanuatu), serving cooking and storage needs; stone adzes remained essential for arboriculture and canoe building.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Reef-pass and leeward-coast sailing lanes joined island clusters (e.g., Santo–Efate–Tanna, Viti Levu–Lau, Guadalcanal–Malaita–Makira).

-

Wind-season calendars structured long voyages: downwind movements during trade-wind peaks; inter-island visits timed to harvests and ceremonial cycles.

-

Ceremonial circuits linked grade promotions, marriage exchanges, and peace-making feasts across neighboring islands.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Ancestral power (mana) infused land, pigs, and shell valuables; tabu prescriptions governed access to sacred groves, stones, and fishing grounds.

-

Ritual houses displayed clan emblems and ancestor relics; drums, slit-gongs, and conch trumpets synchronized feasts and grade rites.

-

Pig-tusk symbolism and shell-ring valuables indexed rank and ritual achievement; exchange enacted social bonds and cosmological balance.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Multi-ecosystem subsistence—gardens + reef + lagoon + upland foraging—spread risk against cyclones and drought.

-

Ritual redistribution (grade feasts, compensation payments) reallocated surplus to stressed communities, stabilizing alliances.

-

Settlement flexibility—coastal hamlets paired with defensible ridge sites—reduced vulnerability to raid and sudden resource failure.

-

Inter-island reciprocity ensured salt, cordage, adze stone, and ceremonial goods moved where needed.

Long-Term Significance

By 963 CE, East Melanesia sustained stable, ritually integrated chiefdoms:

-

Vanuatu’s grade societies transformed pigs and shell valuables into political authority and social cohesion.

-

Fiji consolidated coastal–inland networks supported by irrigated valleys and defensible ridge settlements.

-

Solomon Islands and New Caledonia balanced lagoon fisheries with yam/taro horticulture under lineage leadership.

These systems formed the institutional and economic platform for later fortified hill settlements, expanded canoe exchange, and the intensifying Fiji–Vanuatu–Solomons interaction sphere in the following age.

West Melanesia (820 – 963 CE): Highlands Gardens, Men’s Houses, and Sea-Lanes of the Bismarck

Geographic and Environmental Context

West Melanesia includes New Guinea, Bougainville (the northern Solomon Islands), and surrounding smaller islands (e.g., the Bismarck Archipelago: New Britain, New Ireland, Manus, and the Trobriand/Massim groups).

-

A steep cordillera splits New Guinea, dropping to vast lowland swamps (Papuan Gulf) and big river systems (Sepik, Ramu, Fly).

-

To the northeast, the Bismarck Sea and Vitiaz Strait knit high islands and reef-ringed coasts into dense canoe corridors; Bougainville–Buka sit at the hinge with the Solomons.

-

Ecologies range from montane gardens to sago wetlands, mangrove estuaries, and reef lagoons.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

Warm, humid tropics with strong orographic rainfall on windward slopes; brief dry seasons in some leeward pockets.

-

El Niño–Southern Oscillation swings produced patchy droughts in some years (especially in rain-shadow valleys), countered by diversified cropping and exchange.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Highlands (Wahgi, Asaro, Simbu, Enga): populous villages organized by clans and sub-clans; leadership was competitive and achieved—“big-men” mobilized labor for gardens, feasts, and compensation payments. Defensive palisades and ridge-top hamlets appeared where rivalry was acute.

-

Sepik & North Coast: men’s cult houses (haus tambaran) anchored ritual–political life; riverine communities balanced sago, fish, and carving economies, with ritual specialists guiding inter-clan diplomacy.

-

Papuan Gulf & South Coast: stilt-house villages coordinated sago processing, shellwork, and long estuarine voyages; early forms of Hiri-type seasonal trading (later famous among Motu) likely had precedents in this period.

-

Bismarck Archipelago (New Britain/New Ireland/Manus): coastal chiefdomlets leveraged canoe fleets; obsidian (e.g., Talasea sources on New Britain) and fine shell goods moved widely.

-

Massim/Trobriands & adjacent groups: inter-island gift exchange spheres (precursors to later kula circuits) linked islands by ceremonial partnerships and specialist craft.

-

Bougainville–Buka: ranked lineages managed shell-ring valuables, pig herds, and reef rights; coastal–interior alliances balanced competition and trade.

Economy and Trade

-

Staples: highland taro, yam, banana, sugarcane, sweet potato (regionally variable, expanding but not yet universal); lowland sago and coastal fishing/shellfish.

-

Pigs: prime ceremonial wealth for bridewealth, compensation, and feasts.

-

Exchange networks:

-

Highlands–lowlands: salt, stone adzes, bird-of-paradise plumes, and pigs moved against sago, shells, and coastal goods.

-

Bismarck Sea lanes: obsidian, shell valuables, red feathers, canoe hulls, and cured fish circulated between New Britain, New Ireland, Manus, and the north coast of New Guinea.

-

Bougainville–Buka: shell-ring currencies and pigs structured regional wealth and diplomacy.

-

Subsistence and Technology

-

Garden engineering: ditched/raised beds and drainage fields in wetter highland basins; mounding and mulching for yams; terrace edges on slopes; tree-crop (pandanus) management in montane zones.

-

Lowlands: sago groves, fish traps, and mangrove exploitation; smoking and drying extended shelf-life of fish and meat.

-

Canoes: large outrigger sailing canoes with crab-claw or spritsails for open passages; river canoes for Sepik–Ramu transport.

-

Craft: ground-stone adzes, shell knives, bone points; selected areas maintained local pottery traditions (coastal/Bismarck), while many highlands lacked ceramics.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Vitiaz Strait & Bismarck Sea formed the main maritime arterials—New Britain ⇄ north New Guinea ⇄ New Ireland/Manus.

-

Sepik–Ramu–Markham and Highlands–Ramu portages linked river basins to north-coast shipping.

-

Papuan Gulf estuary routes carried sago and shellwork west–east; Bougainville–Buka straits tied northern Solomons to the Bismarck web.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Ancestral skulls, spirit boards, and men’s houses materialized ties to founding beings and land; ritual secrecy governed initiation and cult performance.

-

Feast/compensation cycles converted pigs and shells into social credit, mending conflicts and forging alliances.

-

Sepik river art—carved masks, totems, and painted façades—expressed clan myths and territorial claims; coastal shrines protected voyagers and reefs.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Poly-resource subsistence (gardens + pigs + sago + fisheries) buffered droughts and crop disease; staggered planting and varietal diversity reduced risk.

-

Defensible settlements and alliance networks mitigated warfare losses; exchange partnerships reopened trade after conflict.

-

Obsidian–shell circuits spread essential cutting edges and wealth tokens across wide distances, stabilizing technology and diplomacy.

Long-Term Significance

By 963 CE, West Melanesia sustained a densely networked archipelago of gardens, men’s houses, and canoe corridors:

-

Highland big-man polities orchestrated labor and ritual through surplus and pigs;

-

Sepik and north-coast riverine societies aligned cult houses with trade;

-

Bismarck and Massim islands carried a maturing ceremonial exchange economy;

-

Bougainville–Buka balanced rank, reef tenure, and shell wealth.

These institutions—engineered gardens, ritual economies, and sea-lanes—provided the durable framework for the intensified fortifications, inter-island alliances, and long-distance ceremonial exchange that would mark the following age.