Southeast Asia

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 70 total

The Indian Ocean World, one of the twelve divisions of the Earth, is centered on the Indian Ocean and encompasses Madagascar, several small island groups, Maritime East Africa, Southeastern Arabia, Southern India, Sri Lanka, and Aceh—the northernmost tip of Sumatra. Its southernmost point is Kerguelen Island.

To the north of Madagascar, the island nations of the Comoros and the Seychelles are situated in the western Indian Ocean, while Mauritius lies to the east of the great island.

On the African mainland, the region includes portions of Mozambique, Malawi, Tanzania, Kenya, and Somalia, all of which also have cultural and historical ties to Afroasia.

The Arabian nations of Yemen and Oman face the heart of the Indian Ocean World, with their division aligning with the traditional boundary separating North India from South India and Sri Lanka.

To the west of Southern India, the Maldives form a prominent island chain within this maritime world.

Along the northeastern boundary, only Aceh, the northwesternmost tip of Sumatra, belongs to the Indian Ocean World, distinguishing it from the rest of the Indonesian archipelago.

HistoryAtlas contains 1,059 entries for the Indian Ocean World from the Paleolithic period to 1899.

Narrow results by searching for a word or phrase or select from one or more of a dozen filters.

The Moderns are taller, more slender, and less muscular than the Neanderthals, with whom they share—perhaps uneasily—the Earth.

Though their brains are smaller in overall size, they are heavier in the forebrain, a difference that may allow for more abstract thought and the development of complex speech.

Yet, the inner world of the Neanderthals remains a mystery—no one knows the depths of their thoughts or how they truly expressed them.

The descendants of the immigrants to West Asia who had remained in the south (or taken the southern route) had spread generation by generation around the coast of Arabia and the Iranian plateau until they reached India.

One of the groups that had gone north (east Asians were the second group) had ventured inland and radiated to Europe, eventually displacing the Neanderthals.

They had also radiated to India from Central Asia.

The former group headed along the southeast coast of Asia, reaching Australia between fifty-five thousand and thirty thousand years ago, with most estimates placing it about forty-six thousand to forty-one thousand years ago.

Sea level is much lower during this time, and most of Maritime Southeast Asia is one land mass known as the lost continent of Sunda.

The settlers probably continued on the coastal route southeast until they reached the series of straits between Sunda and Sahul, the continental land mass that was made up of present-day Australia and New Guinea.

The widest gaps are on the Weber Line and are at least ninety kilometers wide, indicating that settlers had knowledge of seafaring skills.

Archaic humans such as Homo erectus never reached Australia.

If these dates are correct, Australia was populated up to ten thousand years before Europe.

This is possible because humans avoided the colder regions of the North favoring the warmer tropical regions to which they were adapted given their African homeland.

Another piece of evidence favoring human occupation in Australia is that about forty-six thousand years ago, all large mammals weighing more than one hundred kilograms suddenly became extinct.

The new settlers were likely to be responsible for this extinction.

Many of the animals may have been accustomed to living without predators and become docile and vulnerable to attack (as will occur later in the Americas).

The small population of moderns had spread from the Near East to South Asia by fifty thousand years ago, and on to Australia by forty thousand years ago, Homo sapiens for the first time colonizing territory never reached by Homo erectus.

It has been estimated that from a population of two thousand to five thousand individuals in Africa, only a small group, possibly as few as one hundred and fifty to one thousand people, crossed the Red Sea.

Of all the lineages present in Africa only the female descendants of one lineage, mtDNA haplogroup L3, are found outside Africa.

Had there been several migrations one would expect descendants of more than one lineage to be found outside Africa.

L3's female descendants, the M and N haplogroup lineages, are found in very low frequencies in Africa (although haplogroup M1 is very ancient and diversified in North and Northeast Africa) and appear to be recent arrivals.

A possible explanation is that these mutations occurred in East Africa shortly before the exodus and, by the founder effect, became the dominant haplogroups after the exodus from Africa.

Alternatively, the mutations may have arisen shortly after the exodus from Africa.

Some genetic evidence points to migrations out of Africa along two routes.

However, other studies suggest that only a few people left Africa in a single migration that went on to populate the rest of the world, based in the fact that only descents of L3 are found outside Africa.

From that settlement, some others point to the possibility of several waves of expansion.

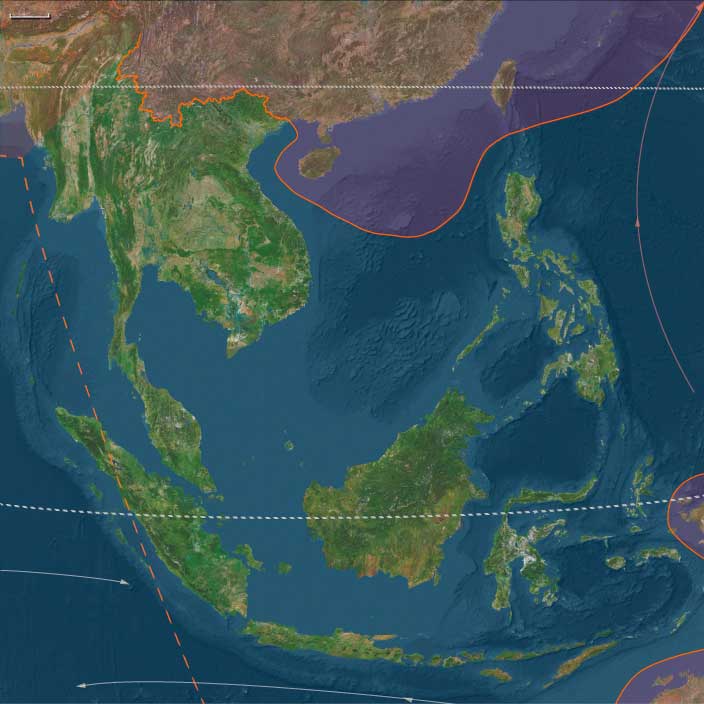

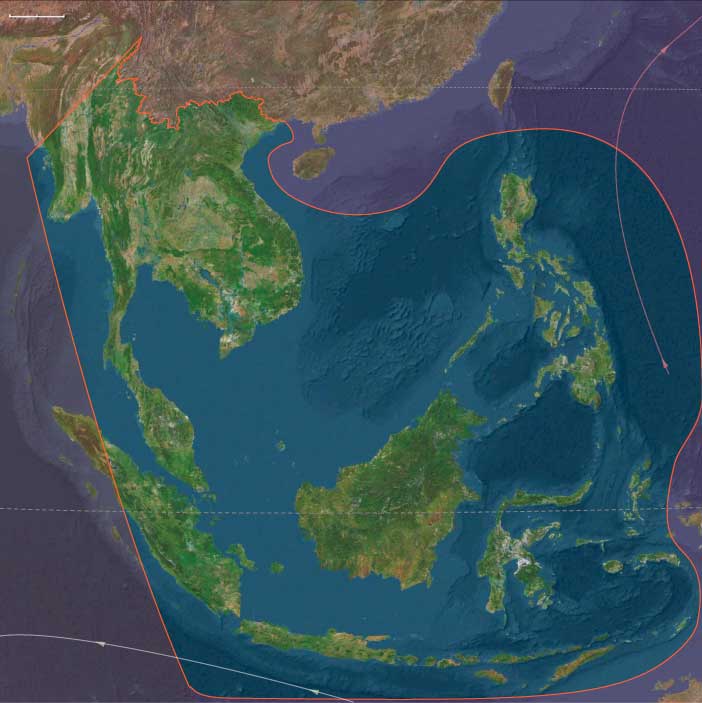

Southeast Asia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — Sundaland Continents, Island Worlds, and the Dawn of Rock Art

Geographic & Environmental Context

At the height of the Late Pleistocene glacial world, Southeast Asia presented two contrasting landscapes — the broad, continental plains of Sundaland and the fragmented islands of Wallacea and Andamanasia — together forming one of the planet’s richest and most diverse human realms.

-

Sundaland: With sea level 50–120 meters below present, the exposed shelf united Sumatra, Java, Borneo, and the Malay Peninsula into a single subcontinent threaded by enormous rivers (paleo-Mekong, Mahakam, Kapuas, Brantas, Musi). Its coastlines stretched hundreds of kilometers beyond today’s shores, forming wide savanna–forest mosaics, mangrove-fringed estuaries, and lagoons teeming with life.

-

Wallacea: Beyond the drowned shelf lay Sulawesi, the Moluccas, Banda, Halmahera, Timor, and the Philippines—a chain of volcanic and limestone islands divided by deep channels marking the Wallace Line. These crossings demanded deliberate navigation and early maritime technology.

-

Andamanasia: To the northwest, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, together with Aceh’s offshore arcs (Simeulue–Nias–Mentawai), Preparis–Coco, and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, formed isolated forested refugia edging the exposed Sunda shelf. Their reefs, mangroves, and turtle beaches stood largely unpeopled but ecologically robust.

This region, straddling the equatorial monsoon belt, offered every possible habitat: mountains, caves, mangroves, coral reefs, and inland plains—each a seasonal hub for late Pleistocene foragers.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Early Period (49–40 ka): Alternating warm–wet and cool–dry pulses governed by orbital forcing and monsoon strength. Forests waxed and waned, while lower sea levels extended savannas across exposed shelf flats.

-

Mid–Late Period (40–30 ka): Cooler, drier glacial trend; rivers incised deeper valleys, and interior lakes and wetlands shrank. On Sundaland, open woodlands and grasslands expanded, while the monsoon weakened and the dry season lengthened.

-

Approach to the LGM (after 30 ka): Intensified aridity inland; coastal productivity remained high as cold upwelling zones enriched fisheries. In Wallacea and Andamanasia, rainfall persisted in volcanic uplands and cloud-forest refuges, sustaining biodiversity through the glacial maximum.

These climatic oscillations required mobility and ecological flexibility, drawing humans toward coasts and river corridors where food remained predictable.

Human Societies and Lifeways

Sundaland Foragers

-

Population & Organization: Small, mobile bands of hunter–fishers numbering a few dozen individuals, moving seasonally between river valleys, forests, and estuaries.

-

Subsistence:

• Terrestrial: red deer, wild cattle (banteng), pigs, and forest birds; fruit, tubers, nuts, and honey.

• Aquatic: riverine fish, turtles, mollusks, and estuarine shellfish.

• Fire management maintained patchy mosaics that attracted game and improved travel routes. -

Settlements: Open camps along paleo-rivers and karstic caves (Lang Rongrien, Niah, Tabon) served as wet- and dry-season bases.

Wallacean Islanders

-

Maritime Expansion:

Short but deliberate crossings linked Bali–Lombok, Sulawesi, the Moluccas, and the Philippines. Voyagers likely used bamboo rafts or dugout craft, already capable of island-hopping across swift straits. -

Economy:

Coastal and reef exploitation dominated: fish, shellfish, turtles, and seabirds; inland forests provided sago palms, fruits, and nuts. -

Symbolism:

The world’s earliest known figurative rock art—hand stencils and painted animals in Sulawesi and Borneo (≥40,000 BP)—emerged here, marking one of humanity’s earliest symbolic revolutions.

Andamanasian Refugia

-

Status: Probably uninhabited or sparsely visited; nearby shelf coasts were rich in mangroves, turtles, and seabirds.

-

Role: Served as ecological storehouses—dense forests and reefs sustaining species that would repopulate coastlines when sea levels rose.

Technology & Material Culture

Across the region, technological diversity mirrored environmental range:

-

Stone industries: Large flakes, blades, and denticulates; hafted spear points and knives. Toolkits adapted to mixed forest and aquatic settings.

-

Organic tools: Bone and shell awls, barbed points, and fish gorges; woven nets and basketry inferred from indirect evidence.

-

Pigment and ornament: Red ochre for body painting and adhesive binders; perforated shell, tooth, and bone beads as markers of identity and alliance.

-

Fire technology: Controlled burning reshaped landscapes for hunting and plant gathering.

-

Maritime engineering: Simple rafts or canoes allowed crossing of deep channels—among the earliest seafaring experiments on Earth.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

River Arteries: The paleo-Mekong, Mahakam, and Kapuas systems functioned as “interior highways,” linking uplands to the exposed shelf coastlines.

-

Maritime Crossings:

• Wallace Line passages—Bali–Lombok, Makassar Strait, Molucca gaps—connected hunter–gatherer populations despite fierce currents.

• Philippine corridors—Luzon–Visayas–Mindanao and the Sulu arc—fostered early trade in shell, pigment, and worked bone.

• Andaman–Nicobar chains paralleled the Sunda coastline, possibly sighted but not yet permanently occupied.

These overlapping networks formed the world’s earliest complex seascape of interaction, prefiguring Holocene navigation traditions.

Belief and Symbolism

Southeast Asian peoples by this time had developed a sophisticated symbolic world:

-

Cave and rock art in Sulawesi, Borneo, and Palawan reveal enduring mythic narratives—animals, hand stencils, and spirit figures linked to hunting and fertility.

-

Ochre rituals and bead ornaments signified personal and group identity.

-

Animistic cosmologies likely centered on water, rock, and ancestral spirits inhabiting caves, springs, and trees—beliefs that would echo in later Austronesian spiritual systems.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Adaptation was rooted in mobility, flexibility, and knowledge sharing:

-

Ecological diversity—forests, coasts, savannas, and rivers—allowed resource substitution during climate downturns.

-

Fire and water mastery reshaped landscapes and improved predictability.

-

Distributed knowledge networks—oral mapping of water sources, seasonal winds, and fauna—anchored community resilience.

-

Littoral foraging provided a caloric safety net through the harshest glacial episodes.

These strategies ensured persistence through one of the most variable climatic regimes on Earth.

Long-Term Significance

By 28,578 BCE, Southeast Asia had achieved a remarkable cultural and ecological synthesis:

-

The Sundaland–Wallacea continuum fostered societies adept at both land-based and maritime living.

-

Rock art, ornamentation, and pigment use announced an enduring symbolic sophistication.

-

Island-hopping navigation and inter-band exchange forged the first Pacific seafaring tradition.

These foundations—broad-spectrum foraging, flexible mobility, and deeply symbolic worldviews—would underpin every later cultural transformation of the region, from Holocene coastal settlement to Neolithic agriculture and, millennia later, the great Austronesian voyaging dispersals that carried Southeast Asia’s legacy across the entire Pacific.

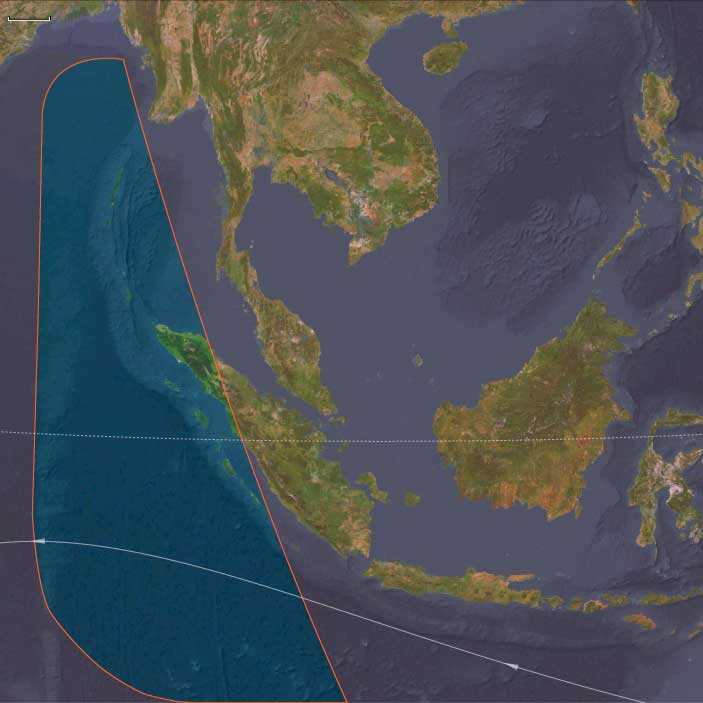

Andamanasia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE) Upper Pleistocene I — Ice-Age Shelves, Reef Flats, and Island Forest Refugia

Geographic and Environmental Context

Andamanasia encompasses:

-

Andaman Islands (North, Middle, South Andaman) and Nicobar Islands.

-

Aceh in northern Sumatra, with nearby islands (Simeulue, Nias, Batu, Mentawai).

-

The Cocos (Keeling) Islands.

-

The Preparis, Coco, and Little Coco Islands (off Myanmar).

Anchors: North–South Andaman coasts and reefs, Nicobar Great Channel, Aceh’s Weh Island and Lhokseumawe–Banda Aceh corridor, Simeulue–Nias–Mentawai arc, Preparis/Coco islets, Cocos (Keeling) lagoon.

-

Sea level ↓ ~100 m: Sunda Shelf largely exposed, connecting Sumatra to mainland SE Asia; Andamans/Nicobars remained island chains but closer to coastlines.

-

Islands: forested Andamans; Nicobars with mangrove–reef systems; offshore islands (Cocos, Preparis) exposed limestone flats.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Glacial maximum: cooler SSTs, stronger winter monsoon winds; rainfall suppressed, but coastal mangroves and refugia persisted.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Likely unpeopled yet, though possible transient visits from early coastal voyagers hugging Sunda margins.

-

Rich seabird/turtle rookeries, mangrove crabs, and reef fish provided high productivity if reached.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Not directly evidenced, but contemporaneous SE Asian foragers used flake/microblade toolkits; dugouts or bamboo rafts possible for coastal movement.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Sunda coastal highway skirted Nicobar–Andaman arc; exposed shelf meant short crossings from Sumatra → Nicobars → Andamans.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

None directly known; symbolic life inferred from mainland contexts (ochre, ornaments).

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

These islands acted as ecological storehouses awaiting human settlement.

Transition

By 28,578 BCE, Andamanasia’s forest–reef mosaics had matured as refugia; human settlement awaited deglaciation.

The Arrival of Early Modern Humans in Eurasia

Homo sapiens sapiens, the same physical type as modern humans, appeared in various regions by at least 50,000 BCE. These Early European Modern Humans (EEMH), formerly known as Cro-Magnon peoples, represent the first anatomically modern humans in Europe.

Migration into Eurasia

- Early modern humans entered Eurasia via the Arabian Peninsula approximately 60,000 years ago.

- One group rapidly settled coastal areas around the Indian Ocean, expanding into South and Southeast Asia.

- Another group migrated north, reaching the steppes of Central Asia and eventually spreading into Europe.

Coexistence with Neanderthals

- Neanderthals and modern humans coexisted across Europe and western Asia for thousands of years.

- Evidence suggests that interactions may have been peaceful, with possible cultural exchanges.

Interbreeding and Genetic Legacy

- Genetic studies indicate that Neanderthals and modern humans interbred occasionally, with non-African populations today carrying traces of Neanderthal DNA.

- However, there is no strong evidence supporting the existence of true Neanderthal-modern hybrids as a distinct population. Instead, interbreeding events were limited, contributing only small genetic fragments to the modern human genome.

The arrival of modern humans in Eurasia marked a significant turning point, eventually leading to the replacement of Neanderthals, though traces of their genetic legacy remain in human populations today.

Southeast Asia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene — Deglaciation, Island Worlds, and the Age of Painted Caves

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Late Pleistocene and early Holocene, Southeast Asia transformed from a single vast continent—the Sunda Shelf—into the world’s largest archipelagic region.

As glaciers melted and sea level rose more than 100 m, the ancient plains that once joined Sumatra, Borneo, Java, and the Malay Peninsula vanished beneath the sea.

By 8,000 BCE, the modern configuration of islands, peninsulas, and straits had formed, creating the fragmented landscapes that define Southeast Asia today.

Two great cultural-ecological spheres emerged:

-

Southeastern Asia (mainland and Sundaic islands: Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Sumatra, Java, Borneo, Sulawesi, the Philippines, and surrounding seas) — a region of rock-shelter cultures, reef-foragers, and early voyagers.

-

Andamanasia (Andaman–Nicobar–Aceh–Mentawai arc) — a bridge corridor between the Bay of Bengal and the eastern Indian Ocean, where island foragers first adapted to rising seas through mobility and exchange.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The transition from the Last Glacial Maximum to the Holocene thermal optimum reshaped every ecosystem:

-

Last Glacial Maximum (c. 26,500 – 19,000 BCE): cooler, drier conditions contracted tropical forests; open grasslands dominated the Sunda Shelf; coasts extended hundreds of kilometers seaward.

-

Bølling–Allerød (c. 14,700 – 12,900 BCE): abrupt warming and intensified monsoons regenerated rainforests, flooded valleys, and boosted reef productivity.

-

Younger Dryas (12,900 – 11,700 BCE): a brief return to cooler, drier climates reduced forest cover and lowered rainfall; many groups pivoted toward coastal and riverine foraging.

-

Early Holocene (after 11,700 BCE): renewed warmth and humidity stabilized monsoons, expanded mangroves, and created the modern deltaic and island environments of the region.

The sea’s advance transformed the old Sundaic plains into the Java, South China, and Andaman Seas, generating new migration corridors and refuges.

Subsistence & Settlement

Late Pleistocene–Holocene communities practiced broad-spectrum foraging, balancing marine and terrestrial resources as coasts shifted:

-

Mainland & Sundaic islands:

Cave and rock-shelter settlements proliferated—Niah (Borneo), Lang Rongrien (Thailand), Tabon (Palawan)—where people hunted deer, pigs, and macaques; gathered tubers, nuts, and fruit; and harvested shellfish, reef fish, and turtles.

As shorelines retreated inland, estuarine fisheries and mangrove gathering replaced the vast riverine plains of the glacial period. -

Andaman–Nicobar–Aceh–Mentawai arc:

Canoe-borne foragers settled the Andaman and Nicobar Islands early, maintaining mixed forest–littoral economies of wild yams, deer, pigs, fish, and turtle.

Nicobars and Mentawais saw itinerant villages around lagoons and palm belts, while Aceh’s capes supported estuarine hunters and reef gleaners.

The Cocos and Preparis islets remained largely uninhabited but intermittently visited.

Across the region, settlements cycled between coastal and upland zones, tracking resource pulses through seasonal mobility.

Technology & Material Culture

Technological versatility matched the diversity of habitats:

-

Blade–microlith industries adapted to hunting and woodworking.

-

Ground-stone adzes and shell tools appeared for tree felling and canoe shaping.

-

Bone harpoons and fish gorges expanded marine exploitation.

-

Nets, baskets, and bark containers aided storage and mobility.

-

Ornaments in shell, bone, and stone expressed group identity, while ochre marked both body and rock.

-

The period’s most enduring legacy lay in Sulawesi’s cave art, where hand stencils and depictions of babirusas and deer-pigs—painted more than 40,000 years ago and renewed in this epoch—attest to a continuous symbolic tradition of exceptional depth.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Rising seas did not isolate communities—they reorganized movement:

-

Philippines–Sulawesi–Moluccas–Banda arc: voyaging intensified along visible island chains; short open-sea hops of 50–100 km created one of the earliest sustained maritime networks on Earth.

-

Andaman–Nicobar–Aceh–Mentawai corridor: canoe routes linked rainforests and reefs, establishing exchange of shell, resin, and ochre long before later Austronesian expansion.

-

Mainland river valleys (Irrawaddy, Chao Phraya, Mekong, Red) remained arteries of movement, connecting highland hunters to emerging coastal fisheries.

In effect, Southeast Asia became a maritime crossroads, not a fragmented world.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Symbolic life flourished amid environmental flux:

-

Cave art and engraving traditions expanded across Sulawesi, Borneo, and mainland karsts.

-

Ritual burials with ochre, shell ornaments, and pig or turtle offerings emphasized ancestry and connection to place.

-

Portable ornaments—beads, pendants, animal carvings—spread widely, perhaps marking alliance networks.

-

In Andamanasia, shell-midden cemeteries and ritual fires expressed continuity across generations as shorelines advanced.

The human imagination here turned environmental change into cosmology, reflecting a worldview of islands as living entities linked by sea and spirit.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Adaptation relied on mobility, diversity, and exchange:

-

Coastal intensification—shellfish, reef fish, and turtle harvesting—buffered inland droughts during the Younger Dryas.

-

Forest knowledge systems diversified diets and materials; edible tubers, palms, and resinous trees provided fallback foods and technology.

-

Canoe voyaging maintained inter-island ties, reducing risk from local resource failure.

-

Populations tracked mangrove succession and coral growth, continuously resettling new lagoons as older coasts drowned.

The region’s peoples evolved a unique maritime–terrestrial dualism that would persist into later Holocene societies.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, Southeast Asia had become a world of islands, caves, and canoes—a landscape defined by water, art, and mobility.

-

Southeastern Asia saw its great painted caves, the flourishing of maritime foraging, and the first truly island-based societies.

-

Andamanasia established continuous human occupation across its archipelagos, anticipating later Indian Ocean seafaring.

The epoch’s legacy was both environmental and cultural: a blueprint for the seagoing economies and symbolic richness that would, millennia later, carry Austronesian speakers and their descendants across the Indo-Pacific.