Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 43 total

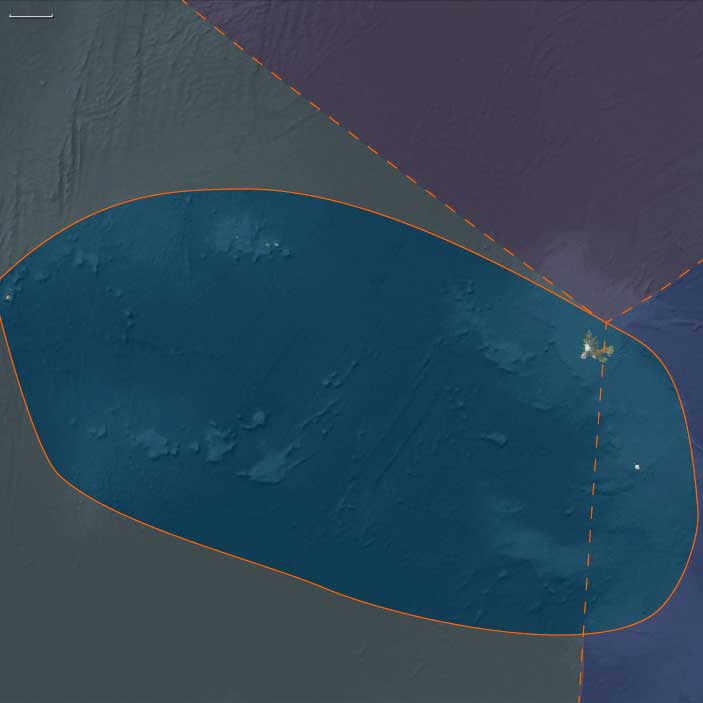

Southern Indian Ocean (49,293–28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — Glacial Frontiers and the Subantarctic Living Sea

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the height of the last Ice Age, the Southern Indian Ocean world—composed of the Southeast Indian Ocean subregion (Kerguelen east of 70°E, Heard, and McDonald Islands) and the Southwest Indian Ocean subregion(western Kerguelen, the Îsles Crozet, and Prince Edward–Marion Islands)—stood as a scattered constellation of volcanic outposts astride the circumpolar current.

Together, these two subregions formed the northern ramparts of Antarctica’s climatic realm: bleak, wind-lashed, yet biologically exuberant. Their high plateaus and coastal shelves were carved by ice and pummeled by the Southern Ocean’s furious westerlies. Kerguelen, the “Great Southern Land” of the subantarctic, spanned nearly 7,000 square miles of basaltic uplands, glaciers, and fjorded coasts—dwarfing its neighbors. To the west, the Crozet and Prince Edward groups rose as serrated volcanic cones; to the east, Heard and McDonald smoldered on the oceanic horizon. Sea levels 60–90 m lower than today broadened their near-shore benches, but their cliffs and mountains ensured that even exposed shelves were narrow.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

Throughout this span, the Last Glacial Maximum gathered strength.

-

Atmosphere & Temperature: Mean annual temperatures were several degrees colder than today, and precipitation fell mostly as snow. Ice caps mantled Kerguelen’s highlands and the summits of Heard and Crozet.

-

Winds & Currents: The westerly storm belt intensified; katabatic outflow from Antarctica sharpened the pressure gradient, amplifying the “roaring forties” and “furious fifties.”

-

Ocean Systems: The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) tightened around the islands, churning nutrient-rich upwellings that fueled one of Earth’s great marine food webs.

-

Sea Level: Lower global sea level expanded intertidal zones and ice-free headlands but did little to change the islands’ rugged relief.

The result was an environment at once extreme and thriving—a cold oceanic oasis in which ice, wind, and water sustained a chain of life from krill to whale.

Ecosystems & Biotic Communities

Though uninhabited by humans, these islands pulsed with ecological energy.

-

Terrestrial life: Sparse subantarctic tundra—mosses, lichens, cushion plants, and graminoids—colonized lee slopes and moraines. On Kerguelen’s western plateaus and Heard’s lower benches, periglacial soils nurtured mats of hardy vegetation that trapped moisture and nitrogen from seabird guano.

-

Avifauna: Albatrosses, petrels, skuas, and penguins established immense rookeries, their cycles governed by ice advance and retreat.

-

Marine mammals: Seals and elephant seals hauled out on the few ice-free beaches; whales traced annual feeding migrations through the ACC’s plankton blooms.

-

Marine productivity: Krill, squid, and small pelagic fish flourished in cold upwelling zones, knitting together a trans-oceanic ecosystem that linked Antarctica, Africa, and Australasia.

These biological systems recycled nutrients with astonishing efficiency; seabird guano and seal carcasses fertilized soils, and winds redistributed minerals across the ocean surface—an unbroken loop of energy long before any human witness.

Human Absence and Global Context

Elsewhere across the planet, Upper Paleolithic peoples perfected blade industries, tailored clothing, and art traditions, but no seafarers had ventured this far south. The subantarctic islands lay well beyond the reach of any Pleistocene navigation system. Their extreme latitude, relentless weather, and lack of fuel or timber would have defeated even the most adaptable hunter-gatherers.

Their absence, however, highlights a global contrast: while Eurasian and African foragers filled temperate landscapes with symbols and settlements, the Southern Indian Ocean remained the great unpeopled wilderness, its only networks those of wind, current, and migration.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Even without humans, the region was laced with biological highways:

-

The ACC carried nutrients and drifting plankton eastward around the world, feeding a continuous belt of marine life.

-

Migratory whales and seabirds followed these currents seasonally, moving between Antarctic feeding grounds and temperate breeding sites.

-

The islands themselves acted as stepping-stones for non-human travelers—rookeries, haul-outs, and rest sites—linking ecosystems thousands of kilometers apart.

These corridors, carved by wind and current, pre-figured the oceanic routes that human mariners would one day exploit.

Symbolic and Conceptual Dimensions

To the Ice-Age imagination, had these lands been known, they would have represented the edge of the habitable world—a mythic margin where ocean, ice, and sky merged. In reality they lay beyond any cultural horizon, silent witnesses to global climatic drama, unmarked by tools or fire.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Across glacial cycles, these ecosystems displayed remarkable resilience:

-

Vegetation persisted in sheltered micro-refugia, recolonizing freshly deglaciated ground after each cold surge.

-

Seabirds and seals adjusted breeding sites in rhythm with ice extent.

-

Nutrient cycling remained intact through redundancy: if one rookery failed, others thrived along the current.

This flexibility forged an enduring ecological template that would persist into the Holocene and still defines the subantarctic today.

Transition Toward the Glacial Maximum

By 28,578 BCE, glaciers on Kerguelen and Heard had reached their broadest limits, and sea ice brushed the northern edge of the ACC. Yet life endured in astonishing abundance.

The Southern Indian Ocean, though untouched by humans, was already a complete, self-regulating world—a chain of volcanic fortresses girdling the planet’s coldest sea. Its twin subregions, Southeast and Southwest Indian Ocean, illustrate precisely the principle that unites The Twelve Worlds: even where no people walked, each subregion lived as its own coherent ecology, bound more closely to kindred zones across oceans than to any continental neighbor. When humanity finally reached these latitudes, the template for adaptation—ice, wind, nutrient, and endurance—was already written in the land itself.

Southeast Indian Ocean (49,293–28,578 BCE): Subantarctic Islands in the Ice Age

Geographic & Environmental Context

The subregion of Southeast Indian Ocean includes Kerguelen east of 70°E and Heard Island and McDonald Islands. These remote volcanic islands rise from the southern Indian Ocean far below the subtropical belt, edging into the subantarctic climatic zone. Kerguelen forms the largest landmass, with its basaltic plateaus, glacial valleys, and fjord-like inlets. Heard Island and the tiny McDonald group lie further east, dominated by the active stratovolcano Big Ben on Heard and barren rocky islets in the McDonalds. Rugged coasts, strong currents, and exposure to prevailing westerlies made these lands biologically and climatically distinct from equatorial or continental environments.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

During this Upper Paleolithic age, global sea levels were 60–90 meters lower than today, reflecting the Last Glacial Maximum’s approach. The islands’ coasts were broader, though steep cliffs and volcanic forms kept much of the shoreline dramatic. The climate was colder, windier, and drier, with glaciers expanding across Kerguelen’s uplands and icefields growing around Big Ben. Snow and ice accumulation carved valleys and extended tongues of ice to the sea. The surrounding Southern Ocean was cooler, nutrient-rich, and dynamic, sustaining upwellings that intensified productivity of marine ecosystems.

Subsistence & Settlement

No humans had yet arrived; these islands remained untouched by people until the modern era. Yet ecosystems flourished. Subantarctic tundra vegetation—mosses, lichens, cushion plants, and grasses—covered exposed surfaces. Freshwater lakes and meltwater streams hosted hardy invertebrates. The seas teemed with krill, fish, and squid, supporting colonies of seabirds and seals. Penguins likely ranged widely across the Southern Ocean during this period, using ice-free coasts for rookeries in warmer interludes. These animal communities created ecological patterns of nutrient cycling and guano fertilization that shaped the islands’ soils long before human presence.

Technology & Material Culture

Though humans had no presence here, this period corresponds globally to advances in Upper Paleolithic stone industries—blade technologies, bone tools, and art traditions in other regions. If transoceanic voyaging had improbably reached these latitudes (something for which there is no evidence), survival would have required mastery of cold-weather adaptations: sewn clothing, sea mammal hunting, and ocean-going craft. The absence of such settlement highlights the remoteness and environmental extremity of the Southeast Indian Ocean islands compared with other subantarctic or continental zones.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The islands lay within the great circumpolar circulation of winds and currents—the roaring forties and furious fifties. Oceanic systems here acted as a conveyor belt for nutrients and migrating species. Marine mammals such as seals, sea lions, and whales followed seasonal routes past Kerguelen and Heard, feeding on the plankton-rich waters. Seabirds traversed vast distances, linking the islands ecologically to Antarctica, Africa, and Australasia. Although no humans traveled these corridors at this time, the patterns they would later rely on—migratory pathways, productive fisheries—were already established.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

There were no cultural expressions tied to these islands in this age. Symbolic activity was flourishing elsewhere: cave paintings in Europe, ritual burials in Asia, and ornaments in Africa. If known, such remote islands might have carried a liminal symbolic weight as places beyond the margins of human habitation. But in this period, they remained outside the human imaginative sphere.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Ecosystems on Kerguelen and Heard demonstrated resilience to glacial fluctuations. Plant life endured in sheltered microclimates, retreating and re-expanding as glaciers advanced and retreated. Bird and seal populations adapted to shifting ice fronts, relocating rookeries and haul-out sites. The islands thus exemplified how subantarctic ecologies reorganize under climatic stress, laying groundwork for the resilience patterns observed into the Holocene.

Transition

By 28,578 BCE, the glacial maximum was approaching, with ice sheets at their most extensive. The Southeast Indian Ocean islands stood as icy outposts, ecologically vibrant but humanly unvisited. Their landscapes were already etched by glaciers, storms, and ocean swells—patterns that would persist until humans finally encountered them millennia later.

Southwest Indian Ocean (49,293–28,578 BCE): Volcanic Arcs in the Subantarctic

Geographic & Environmental Context

The subregion of Southwest Indian Ocean includes Kerguelen west of 70°E, the Îsles Crozet, Prince Edward Island, and Marion Island. These islands rise from the southern Indian Ocean in the storm-lashed belt of the subantarctic. Kerguelen’s western expanses formed the largest landmass of the subregion, with basaltic plateaus and glaciated valleys. The Îsles Crozet, scattered volcanic peaks, lay further west; Prince Edward and Marion Islands anchored the subregion’s southwestern corner. All were rugged, volcanic, and isolated, fringed by steep coasts and pummeled by westerly winds.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

This age coincided with the Last Glacial cycle. Sea levels lay 60–90 meters lower, exposing broader coastal shelves but leaving the islands’ steep relief largely unchanged. Temperatures were colder than today, with advancing glaciers on western Kerguelen and high volcanic plateaus across the Crozet and Prince Edward groups. Fierce katabatic winds from Antarctica mingled with circumpolar westerlies, intensifying storm tracks. Ocean waters were cooler, strengthening upwelling systems that enriched marine productivity around these volcanic arcs.

Subsistence & Settlement

Humans had not yet reached these islands. Their ecosystems, however, were rich. Subantarctic tundra vegetation—mosses, lichens, and cushion plants—established themselves in sheltered niches. Seabird colonies, especially petrels and albatrosses, blanketed cliffs, while penguins and seals occupied ice-free shores. Nutrient cycling from guano deposits fertilized soils, creating patches of biological richness amid volcanic barrenness. Offshore, whales, seals, and seabirds traced migratory corridors that linked these islands to Antarctica, southern Africa, and Australasia.

Technology & Material Culture

Although no people lived here, contemporaneous societies elsewhere in the world were advancing Upper Paleolithic toolkits, symbolic traditions, and survival strategies in cold climates. Had humans reached the subantarctic islands, survival would have required highly specialized technologies: insulated clothing, seaworthy vessels, and methods for exploiting marine mammals. The absence of such evidence underlines the extreme isolation of these islands during this age.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The Southern Ocean circulation swept around these islands, carrying nutrients and sustaining immense food webs. Migrating whales passed seasonally, while seabirds and seals established transoceanic networks of rookeries and feeding grounds. These currents and corridors would one day make the islands strategic for human navigation, but in this age, they were highways only for nonhuman travelers.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

No human symbolic activity is tied to the Southwest Indian Ocean islands in this age. Globally, however, human groups were producing art, ornaments, and ritual sites, embedding meaning in landscapes far from these volcanic outposts. The islands themselves remained unknown and unimagined, lying outside the human cultural horizon.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Life on these islands demonstrated resilience to glacial extremes. Vegetation survived in sheltered microhabitats, recolonizing deglaciated areas as climates fluctuated. Seabird and seal populations shifted breeding sites with changing ice coverage. The capacity of these ecosystems to reorganize under climatic stress foreshadowed the adaptive dynamics that would define their later ecological histories.

Transition

By 28,578 BCE, the glacial maximum was intensifying, with ice reaching peak expansion. The Southwest Indian Ocean islands remained untouched by human hands, yet ecologically vital within the subantarctic marine web. These volcanic arcs stood as stark, wind-battered sentinels, their environments shaped by ice, ocean, and storm.

Southeast Indian Ocean (28,577–7,822 BCE): Ice Retreat and Expanding Shores

Geographic & Environmental Context

The subregion of Southeast Indian Ocean includes Kerguelen east of 70°E and Heard Island and McDonald Islands. Kerguelen’s eastern plateaus and fjord systems dominated the landscape, while Heard Island’s volcanic massif of Big Ben rose above glaciated coasts. The McDonald Islands remained small, rugged, and volcanically active, barely peeking above stormy seas.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

This epoch bridged the Last Glacial Maximum (c. 26,000–19,000 BCE) and the slow deglaciation that followed. Icefields on Kerguelen and Heard expanded dramatically at first, carving valleys and pushing tongues of ice toward the coasts. After 20,000 BCE, retreat began, revealing tundra and freshwater lakes. Sea levels gradually rose—by the end of the epoch, they had climbed tens of meters, re-drowning coastal shelves. The Southern Ocean warmed slightly, altering circulation and plankton blooms.

Subsistence & Settlement

Still uninhabited by humans, the islands were ecologically vibrant. Expanding tundra vegetation reclaimed glacial forelands. Migratory seabirds—especially penguins and petrels—flourished as new rookeries opened on ice-free coasts. Seal and sea lion populations rose in tandem with available haul-out sites. Nutrient cycling intensified, with guano-rich soils anchoring ecosystems. Heard’s volcanic activity intermittently reshaped its surface, creating ash-rich habitats that supported pioneering plant communities.

Technology & Material Culture

Globally, this was the era of Upper Paleolithic florescence: composite tools, bone harpoons, and artistic traditions from Lascaux to the Levant. None reached the Southeast Indian Ocean. Survival here would have demanded advanced maritime craft and cold-weather technologies, beyond the known reach of Paleolithic seafarers.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Marine life moved along the circumpolar current, linking the subregion to Antarctica and Australasia. Whales traced seasonal migrations, while seabirds covered extraordinary distances, knitting together distant ecosystems. These biological corridors laid ecological foundations for later human exploitation of the Southern Ocean.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

No symbolic or cultural activity is tied to these islands. Elsewhere, symbolic traditions exploded: figurines, cave art, and ritual landscapes. The Southeast Indian Ocean remained beyond the human mental map, a space unknown yet ecologically rich.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Plant and animal communities adapted to dramatic climatic shifts—retreating glaciers, rising seas, and fluctuating volcanic activity. Recolonization after ice retreat showcased resilience, as mosses, lichens, and seabird-driven nutrient webs rapidly expanded into new niches.

Transition

By 7,822 BCE, the Ice Age was waning. The Southeast Indian Ocean islands stood transformed: glaciers reduced, coasts reshaped, ecosystems rebounding. Though still unseen by humans, they embodied subantarctic resilience at the cusp of the Holocene.

Southern Indian Ocean (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Upper Pleistocene II → Early Holocene — Deglaciation, Peat Beginnings, and Storm-Belt Resilience

Geographic & Environmental Context

The Southern Indian Ocean spans the sub-Antarctic and high-latitude island arcs that rim the great circumpolar current:

-

Southeast Indian Ocean: Kerguelen (east of 70°E), Heard Island, and the McDonald Islands—a volcanic plateau rising from the central oceanic ridge.

-

Southwest Indian Ocean: Kerguelen (west of 70°E), the Îles Crozet, and the Prince Edward–Marion Islands—low-domed volcanoes and basaltic uplands flanking the Antarctic Convergence.

During this epoch, no humans yet reached these storm-lashed archipelagos. Their story is one of deglaciation, ecological colonization, and the establishment of self-sustaining marine–terrestrial feedbacks that would later define the sub-Antarctic realm.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Last Glacial Maximum (c. 26,500 – 19,000 BCE): Heavy ice mantled Kerguelen’s uplands and Heard’s Big Benmassif. Westerlies circled north of their modern track; sea level stood ~120 m lower, enlarging coastal benches.

-

Bølling–Allerød (c. 14.7 – 12.9 ka): Global warming brought vigorous westerlies and rising seas. Valley glaciers receded, exposing fresh basaltic and till plains that seeded colonizing lichens and cushion plants.

-

Younger Dryas (c. 12.9 – 11.7 ka): A brief cooling and renewed storminess slowed deglaciation; frost-heave and solifluction remodeled slopes.

-

Early Holocene (after 11.7 ka): Temperatures and precipitation stabilized near modern sub-Antarctic norms—cool, windy, and perennially moist. Peat initiation began in sheltered basins; sea level reached present heights, and island coastlines approached their modern outlines.

Subsistence & Settlement

No human occupation occurred. Instead, biotic colonization unfolded in successive waves:

-

Flora: pioneer lichens, mosses, and graminoids occupied leeward slopes; cushion heaths and ferns established as soils thickened. Peat accumulated in depressions, forming the region’s first organic wetlands.

-

Fauna: penguins, petrels, and albatrosses nested on newly ice-free coasts; fur and elephant seals recolonized beaches; burrowing seabirds and arthropods fertilized soils with guano.

-

Marine systems: nutrient-rich upwellings of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) drove high plankton productivity, sustaining krill swarms, baleen whales, and fish shoals that tied the islands into the wider Southern Ocean food web.

Technology & Material Culture

None human. The “technologies” shaping these islands were wind, wave, ice, and ash:

-

Volcanic eruptions at Heard and McDonald periodically spread ash mantles that refreshed mineral nutrients.

-

Freeze–thaw cycles created patterned ground and solifluction lobes—natural engineering that distributed sediments downslope.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Biological and oceanographic circulation replaced human mobility:

-

ACC jets and sub-Antarctic fronts conveyed plankton, krill, and migratory whales around the hemisphere.

-

Seabirds and seals acted as long-distance vectors for nutrients and seeds, linking Crozet–Kerguelen–Prince Edward chains into a metapopulation system.

-

The Westerly storm track itself functioned as a conveyor, cycling moisture and aerosols between South America, Africa, and Australia.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

No human symbolism yet marked these shores. Instead, the ecological rhythms of breeding, molting, and migration inscribed a natural calendar—the biological ritual year of the sub-Antarctic.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Ecosystems here evolved resilience to chronic disturbance:

-

Life-history flexibility—staggered breeding seasons, opportunistic recolonization after landslides or ash falls—ensured continuity.

-

Peatlands and moss carpets buffered moisture extremes, acting as sponges against drought and frost.

-

Guano-driven nutrient cycles maintained fertility despite thin soils and fierce erosion.

Together these feedbacks forged a self-repairing mosaic able to absorb storm scour, ice advance, and volcanic renewal.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, the Southern Indian Ocean had fully entered its Holocene ecological regime: glaciers confined to high cirques, thriving penguin and seal rookeries, expanding peatlands, and nutrient-rich seas linking all sub-Antarctic islands.

Still unseen by humans, these islands already functioned as climate sentinels and biodiversity engines for the Southern Ocean—resilient ecosystems rehearsing the rhythms that would persist into the modern age.

Southeast Indian Ocean (7,821–6,094 BCE): Holocene Beginnings in the Subantarctic

Geographic & Environmental Context

The subregion of Southeast Indian Ocean includes Kerguelen east of 70°E and Heard Island and McDonald Islands. Kerguelen’s fjord-indented eastern coasts and basaltic plateaus were reshaped by glacial retreat, while Big Benon Heard Island remained crowned with ice. The McDonald group continued as small, volcanic outcrops.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

This was the early Holocene, marked by rising global temperatures and accelerating sea-level rise. Glaciers on Kerguelen retreated into upland pockets, and Heard’s icefields shrank, though remaining substantial. Sea levels approached modern levels, submerging exposed shelves from the glacial lowstand. Strong circumpolar westerlies and storm systems continued, though seasonal variability grew with a slightly warmer and wetter climate.

Subsistence & Settlement

Still without human settlement, ecosystems grew increasingly complex. Mosses, lichens, and grasses spread rapidly across deglaciated ground. On Heard and Kerguelen, penguin rookeries expanded as ice-free shores became abundant, while elephant seals and fur seals established dense colonies. Seabird guano enriched soils, accelerating plant colonization. Offshore, whales and fish thrived in plankton-rich upwellings.

Technology & Material Culture

Globally, Holocene societies were beginning to shift toward agriculture in some regions, but such developments lay far from the subantarctic. No material culture touched these islands; their isolation was complete.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current and storm tracks continued to define ecological movement. Migratory species linked these islands with Antarctica, Australia, and Africa. These corridors would one day guide human navigation but remained exclusively biological in this epoch.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

No symbolic or cultural imprint was left here. However, the ecological richness of the islands—seabird gatherings, volcanic peaks, and storm-swept coasts—echoed themes of resilience and endurance that human societies elsewhere were embedding in their ritual landscapes.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

The resilience of life in the subantarctic was clear: seals and penguins adapted to new habitats, plants colonized ash-rich volcanic soils, and ecosystems stabilized under Holocene warmth. Volcanic activity on Heard and McDonald Islands periodically disrupted landscapes, but pioneer vegetation swiftly recolonized.

Transition

By 6,094 BCE, the Southeast Indian Ocean islands stood as thriving ecological refuges of the early Holocene. Still unknown to humans, they embodied the interplay of glacial legacy, volcanic dynamism, and biological resilience.

Southern Indian Ocean (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene — Peat Beginnings, Storm Belts, and Rookery Worlds

Geographic & Environmental Context

The Southern Indian Ocean encompasses two subantarctic island arcs—Kerguelen–Heard–McDonald to the east and Crozet–Prince Edward–Marion to the west—spread across the westerly wind belt of the high southern latitudes.

These islands, volcanic in origin and set within the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC), formed a discontinuous chain of tundra plateaus, ice-capped domes, and cliffed coasts. By the Early Holocene, glaciers had retreated far upslope, revealing fjord-like embayments, peaty basins, and wave-battered beaches alive with seals and seabirds.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Holocene thermal maximum brought modestly warmer, wetter, and more stable conditions than the late glacial:

-

Kerguelen: ice restricted to high cirques; deglaciated valleys supported grass–moss tundra.

-

Heard and McDonald Islands: Big Ben volcano remained glaciated but with expanding ice-free coastal fringes.

-

Crozet–Prince Edward–Marion: frequent gales but longer ice-free summers; steady rainfall encouraged blanket peat initiation.

Sea level neared modern elevations; the ACC and westerlies maintained continuous upwelling and nutrient circulation, ensuring rich marine productivity.

Subsistence & Settlement

No human presence yet reached these latitudes. Instead, ecosystems flourished under pure ecological succession:

-

Vegetation: cushion heaths, moss carpets, lichens, and graminoids stabilized on deglaciated soils; peat accumulated in saturated hollows.

-

Fauna: dense penguin colonies, petrel and albatross nesting cliffs, and seal haul-outs spread across beaches and headlands.

-

Food-webs: guano fertilized tundra soils, supporting arthropods and invertebrate communities that recycled nutrients.

These processes laid the foundation for self-sustaining biogenic landscapes.

Technology & Material Culture

No human artifacts are known. While microlithic and ceramic traditions advanced contemporaneously on continental shores (Africa, India, Australia), the southern islands remained beyond human navigation and survival thresholds.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Only biological corridors connected these islands:

-

ACC jets and fronts concentrated plankton, krill, and squid, feeding whale migrations and pelagic birds.

-

Wide-ranging seabirds (albatrosses, petrels) linked Kerguelen, Crozet, and Marion in a single metapopulation network, carrying nutrients between continents and Antarctica.

-

Volcanic dust and pumice rafts drifted eastward, occasionally seeding new habitats.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

None human, yet natural rhythms created ecological symbolism:

-

Annual breeding cycles of penguins and seals;

-

Molting and migration seasons of seabirds;

-

Glacial surges and volcanic ashfalls marking time in sediment and ice—nature’s own calendar of renewal.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

The subantarctic ecosystem achieved resilience through flexibility and recolonization:

-

Peatlands buffered moisture and nutrients, retaining fertility through storms and droughts.

-

Seabird colonies relocated as shorelines shifted; plants reestablished rapidly after frost or ash disturbance.

-

Marine productivity remained stable under the constant upwelling regime of the ACC.

These systems were robust, self-renewing, and fully autonomous from human disturbance.

Long-Term Significance

By 6,094 BCE, the Southern Indian Ocean islands had reached ecological maturity: glaciers confined to summits, peat widespread in lee basins, and vast colonies of seabirds and seals sustained by one of the planet’s most productive ocean systems.

Still unseen by humankind, these remote lands stood as autonomous laboratories of adaptation—proving that even at the edge of the habitable world, life had engineered stability, resilience, and abundance long before human discovery.

Southern Indian Ocean (6,093–4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Wind Belts, Peat Beginnings, and Rookery Worlds

Geographic & Environmental Context

The Southern Indian Ocean formed a storm-forged crescent of subantarctic islands—Kerguelen (straddling 70°E), Heard and McDonald, and the western arc of Crozet–Prince Edward–Marion—set within the east-flowing Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC). Deglaciated fjorded coasts and plateaus on Kerguelen, the ice-mantled Big Ben massif on Heard, the wave-battered McDonald Islets, and the low-domed cones of Crozet and Prince Edward–Marion together created a tight mosaic of lee-slope tundras, cliff colonies, and kelp-edged bays.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Hypsithermal (Middle Holocene) brought modestly warmer, seasonally steadier conditions than the late glacial: sea level approached modern outlines; westerly wind belts stayed vigorous but more rhythmically phased.

-

Kerguelen: cirque and valley glaciers continued to contract, leaving proglacial lakes and new soils.

-

Heard: outlet glaciers still reached near shore, with episodic ashfalls refreshing mineral substrates.

-

Crozet–Prince Edward–Marion: longer ice-free seasons; peat initiation in saturated hollows began.

Overall, a cool, windy oceanic equilibrium prevailed—harsh to humans, ideal for high-latitude productivity.

Subsistence & Settlement

No human occupation occurred. Ecosystems diversified into self-organizing biogenic landscapes:

-

Vegetation: cushion heaths, moss carpets, lichens, and hardy graminoids advanced upslope and inland; peat hummocks began in lee basins.

-

Fauna: penguin rookeries expanded on cobble beaches; albatross and petrel colonies spread across cliff rims; elephant and fur seals cycled among haul-outs as prey shifted.

-

Aquatic systems: freshwater ponds supported algae and microcrustaceans; kelp forests thickened in semi-sheltered inlets, anchoring nearshore food webs.

Technology & Material Culture

Beyond the subantarctic, continental peoples experimented with microliths, ground stone, and early pottery—but none of these technological ensembles reached this oceanic arc. Any hypothetical human survival would have required ice-worthy boats, sewn insulating garments, and intensive marine processing—packages absent here.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Ecological, not human, traffic structured connectivity. ACC jets and frontal zones concentrated nutrients, driving krill and plankton blooms that drew baleen whales each summer. Albatrosses and petrels stitched Kerguelen–Heard–Crozet–Prince Edward–Marion into a single subantarctic metapopulation network, while volcanic pulses (Heard/McDonald) periodically dusted lee slopes, jump-starting primary succession.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

No human symbolic horizon touched the subregion. Instead, biogenic landmarks—long-used guano terraces, trampling paths, peat-bound seed banks, and rookery berms—functioned like monuments in peopled lands, inscribing ecological memory across generations.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Resilience was layered and dynamic: plants colonized fresh tephra and frost-heave scars; seabird and seal colonies shifted with beach exposure and ice margin retreats; peat initiation buffered moisture and nutrients, diversifying microhabitats. Disturbance (gales, spray, ash) reset patches, maintaining a moving-target mosaic rather than a static climax.

Long-Term Significance

By 4,366 BCE, glaciers had further withdrawn, coastlines lay near modern outlines, and biological networks were robust and self-maintaining. The subantarctic belt entered a stable mid-Holocene regime—still storm-lashed, intensely productive, and unseen by humans—a living laboratory where wind, current, ice, and life tuned one of Earth’s most resilient oceanic ecosystems.

Southeast Indian Ocean (6,093 – 4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Deglaciated Valleys and Expanding Rookeries

Geographic & Environmental Context

The Southeast Indian Ocean realm includes Kerguelen east of 70° E, Heard Island, and the McDonald Islands—a remote arc of volcanic summits, fjorded coasts, and glacial remnants on the northern fringe of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC).

-

Kerguelen’s eastern plateaus had become a network of deglaciated valleys, lakes, and fjords, with new tundra spreading on lee slopes.

-

Heard Island’s Big Ben massif, though still glacier-crowned, now fed proglacial streams through dark ash and gravel plains.

-

The McDonald Islands persisted as low, surf-scoured volcanic stacks, periodically dusted with fresh tephra.

Together these islands formed a mildly warming, biologically awakening corridor between Antarctica and Australasia.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Hypsithermal warm maximum brought temperatures slightly above late-glacial levels and sea levels nearing the modern mark.

Westerly winds stayed strong but became more seasonally regular, producing shorter winters and longer ice-free summers.

Glaciers on Kerguelen retreated into high cirques; Heard retained summit ice but with episodic surges and retreats that refreshed mineral soils below.

Occasional ashfalls from Big Ben and the McDonald Islets’ eruptions renewed nutrient supply, speeding colonization on sheltered slopes.

Subsistence & Settlement

No human presence yet reached these latitudes.

Instead, the mid-Holocene saw a surge of biotic colonization and ecological diversification:

-

Vegetation: cushion plants, mosses, lichens, and hardy grasses spread inland; peat-forming sedges occupied saturated hollows.

-

Fauna: penguin rookeries multiplied on shingle terraces; elephant and fur seals occupied the newly ice-free beaches; albatrosses and petrels nested on higher benches.

-

Ecosystems: guano enrichment created localized fertility “islands,” supporting invertebrate and microbial blooms; in coastal shallows, kelp forests stabilized as year-round feeding habitats.

Technology & Material Culture

No evidence of human visitation exists. Beyond this subantarctic margin, Holocene societies on other continents adopted microlithic toolkits, early ceramics, and complex fishing gear, but none possessed the cold-weather clothing, open-ocean craft, or high-caloric provisioning systems that would have made survival here feasible.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Ecological linkages substituted for human trade:

-

The ACC and associated subantarctic fronts funneled planktonic blooms around the islands.

-

Baleen whales, fur seals, and penguins migrated through these nutrient corridors each summer.

-

Wide-ranging seabirds connected Heard, McDonald, and eastern Kerguelen with feeding grounds toward Antarctica and southern Australasia, forming a single circumpolar metapopulation network.

These flows created biological highways that paralleled, in non-human form, the sea routes future voyagers would someday follow.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

There is no human symbolic record, yet ecological repetition lent the landscape its own temporal rhythm:

nesting cycles, molt seasons, volcanic pulses, and glacial surges created patterns of renewal that gave these islands their natural “calendar of return.”

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Life persisted through rapid recolonization and flexible reproduction:

-

Vegetation recovered swiftly after ashfall and storm scour.

-

Seal and penguin colonies relocated with beach and ice changes.

-

Peat development buffered moisture and temperature, enhancing habitat heterogeneity.

Disturbance, rather than stability, sustained the system—a self-renewing mosaic maintained by wind, ice, and life itself.

Long-Term Significance

By 4,366 BCE, the Southeast Indian Ocean islands had reached near-modern coastlines and hosted mature subantarctic ecosystems: glaciers confined to summits, peat in basins, and dense rookeries along ice-free shores.

Though unvisited by humankind, these islands already functioned as critical biological nodes within the Southern Ocean’s migratory web—a natural laboratory where volcanic renewal, glacial retreat, and marine fertility combined to sustain one of the planet’s most resilient ecological frontiers

Southwest Indian Ocean (6,093–4,366 BCE): Crozet–Prince Edward Arcs in a Mild Holocene Window

Geographic & Environmental Context

The subregion of Southwest Indian Ocean includes Kerguelen west of 70°E, the Îsles Crozet, Prince Edward Island, and Marion Island. Western Kerguelen’s basaltic uplands stepped down to fjord-like embayments; the Crozetgroup rose as fractured volcanic cones; Prince Edward and Marion formed twin, low-domed islands encircled by surf-pounded shelves.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

Mid-Holocene warmth brought longer ice-free seasons and sea levels approaching present. Residual ice on high Kerguelen summits persisted, but valley floors opened to tundra. Westerlies remained dominant, with periodic north–south shifts altering storm frequency. Soils on Crozet and Marion developed thin organic horizons as peat patches began to form in wind-sheltered hollows.

Subsistence & Settlement

No human settlement occurred. Vegetation thickened on leeward slopes—cushion heaths, moss carpets, and graminoids—supporting detrital food webs. Albatross and petrel colonies spread across cliff rims; penguins crowded accessible beaches. Seal populations cycled with prey availability, expanding on beaches newly cleared of winter ice and storm wrack.

Technology & Material Culture

While continental mid-Holocene peoples experimented with ceramics, ground stone, and complex fishing gear, these islands remained beyond the technological and geographic horizons of the time.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The islands sat astride powerful pelagic corridors. ACC jets and frontal zones concentrated nutrients, drawing whales seasonally. Wide-ranging seabirds connected colonies among Crozet, Prince Edward–Marion, and western Kerguelen, forming a coherent subantarctic metapopulation network.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

There is no evidence of human symbolism here. Ecologically, however, recurrent breeding aggregations created long-lived biogenic landmarks—guano platforms, trampling paths, and peat-seed banks—that structured space much like cultural monuments do in peopled landscapes.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Ecosystems absorbed frequent disturbance—gale-driven salt spray, frost heave, and occasional tephra dustings—by rapid recolonization and life-history flexibility (staggered breeding, site fidelity with contingency). Peat initiation in saturated hollows buffered moisture and nutrients, increasing landscape heterogeneity and resilience.

Transition

By 4,366 BCE, the subregion had settled into a mild Holocene window: coastlines near present extent, vegetation entrenched in lee pockets, and marine megafauna using reliable migratory circuits. Human discovery still lay millennia ahead; ecological complexity was already mature.