Liu Bei, the future warlord and founding …

Years: 184 - 184

Liu Bei, the future warlord and founding emperor of the state of Shu Han, was born in Zhuo County, Zhuo prefecture (present day Zhuozhou, Baoding, Hebei), according to the Records of the Three Kingdoms.

He was a descendant of Liu Zhen, the son of Liu Sheng, a son of Emperor Jing.

However, Pei Songzhi's commentary, based on the Dianlue, said that Liu Bei was a descendant of the Marquess of Linyi.

The royal title of Marquess of Linyi wqas held by Liu Fu and later his son Liu Taotu, respectively Liu Yan's grandson and great-grandson, who were all ultimately descended from Emperor Jing.

Liu Bei's grandfather Liu Xiong and father Liu Hong were both employed as local clerks.

Liu Bei had grown up in a poor family, having lost his father when he was still a child.

To support themselves, Liu Bei and his mother sold shoes and straw-woven mats.

Even so, Liu Bei was full of ambition since childhood: he once said to his peers, while under a tree that resembled the royal chariot, that he desired to become an emperor.

Sponsored by a more affluent relative who recognized his potential in leadership, Liu Bei at the age of fourteen had gone to study under the tutelage of Lu Zhi (a prominent scholar and, at the time, former Administrator of Jiujiang).

There he had met and befriended Gongsun Zan, a prominent northern warlord to be.

The adolescent Liu Bei was said to be unenthusiastic in studying and displayed interest in hunting, music and dressing.

Concise in speech, calm in demeanor, and kind to his friends, Liu Bei was well liked by his contemporaries.

He was said to have long arms and large earlobes.

In 184, at the outbreak of the Yellow Turban Rebellion, Liu Bei calls for the assembly of a volunteer army to help government forces suppress the rebellion.

Liu Bei receives financial contributions from two wealthy horse merchants and rallies a group of loyal followers, among whom include Guan Yu and Zhang Fei.

Liu Bei leads his army to join the provincial army.

Together, they score several victories against the rebels.

In recognition of his contributions, Liu Bei is appointed Prefect of Anxi in Zhongshan prefecture.

He resigns after refusing to submit to a corrupt inspector who attempted to ask him for bribes.

He then travels south with his followers to join another volunteer army to suppress the Yellow Turbans remnants in Xu Province (present day northern Jiangsu).

For this achievement, he is appointed Prefect and Commandant of Gaotang.

Locations

People

- Cao Cao

- Gongsun Zan

- Guan Yu

- Huangfu Song

- Ling of Han

- Liu Bei

- Lu Zhi

- Zhang Fei

- Zhang Jue

- Zhao Zhong

- Zhu Jun

Groups

- Taoism

- Chinese (Han) people

- Chinese Empire, Tung (Eastern) Han Dynasty

- Way of the Five Pecks of Rice

Topics

- Han dynasty China

- Disasters of Partisan Prohibitions

- Five Pecks of Rice

- Yellow Turban Rebellion

- Liang Province Rebellion

- Three Kingdoms Period in China

Commodoties

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 60915 total

Zhang Daoling had announced in 142 that Laozi had appeared to him and commanded him to rid the world of decadence and establish a new state consisting only of the ‘chosen people.’

Becoming the first Celestial Master, Zhang had begun to spread his newly founded movement throughout the province of Sichuan.

The movement was initially called the Way of the Five Pecks of Rice, because each person wishing to join was required to donate five pecks of rice.

The movement has spread rapidly, particularly under his son Zhang Heng and grandson Zhang Lu.

The Zhangs have been able to convert many groups to their cause, such as the Bandun Man (belonging to the Ba people), which strengthen their movement.

Zhang Xiu (not related to Zhang Lu) rebels against the Han Dynasty in 184.

Zhang Lu and Zhang Xiu are sent in 191, to conquer the Hanzhong Valley, just north of Sichuan, a city under Zhang Xiu's control.

Zhang Xiu is killed during the subsequent battle, and Zhang Lu establishes the theocratic state of Zhanghan, enjoying full independence.

The Yellow Turban Rebellion, also translated as Yellow Scarves Rebellion, is a peasant revolt that breaks out in 184 in China during the reign of Emperor Ling of the Han Dynasty.

The rebellion, which takes its name from the color of the scarves that the rebels wear on their heads, marks an important point in the history of Taoism due to the rebels' association with secret Taoist societies.

The revolt is also used as the opening event in Luo Guanzhong's historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

The Liang Province Rebellion of 184 to 189 starts as an insurrection of the Qiang peoples against the Han Dynasty in the western province of Liang (Liangzhou, more-or-less today's Wuwei, in the province of Gansu) of second century China, but the Lesser Yuezhi and sympathetic Han rebels soon join the cause to wrestle control of the province away from central authority.

This rebellion, which closely follows the Yellow Turban Rebellion, is part of a series of disturbances that will lead to the decline and ultimate downfall of the Han Dynasty.

Despite receiving relatively little attention in the hands of traditional historians, the rebellion nonetheless has lasting importance, as it removes Han Chinese power in the Northwest and prepares that land for a number of non-Han-Chinese states in the centuries to come.

A coalition of warlords and regional officials in the late Eastern Han Dynasty initiates a punitive expedition against the warlord Dong Zhuo in 190.

The members of the coalition claim that Dong intends to usurp the throne by holding Emperor Xian hostage and by establishing a strong influence in the imperial court.

They justify their campaign as to remove Dong from power.

The campaign leads to the evacuation of the capital Luoyang and the shifting of the imperial court to Chang'an.

It is a prelude to the end of the Han Dynasty and, subsequently, the Three Kingdoms period.

East Central Europe (184–195 CE): Post-Marcomannic Recovery and Frontier Reconstruction

Between 184 and 195 CE, East Central Europe—covering Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, Hungary, and those portions of Germany and Austria lying east of 10°E and north of a line stretching from roughly 48.2°N at 10°E southeastward to the Austro-Slovenian border near 46.7°N, 15.4°E—entered a period of gradual recovery and stabilization following the devastation of the Marcomannic Wars (166–180 CE) and the widespread Antonine Plague (165–180 CE). Under Emperor Commodus (180–192 CE) and his successors, the region experienced significant rebuilding efforts along the Roman Danube frontier, slow economic revitalization, and cautious diplomatic re-engagement with the Marcomanni, Quadi, and Iazyges.

Political and Military Developments

Commodus’s Frontier Policy and Recovery Efforts

-

Under Emperor Commodus, Roman authorities prioritized stabilizing the heavily disrupted Danube frontier provinces—Pannonia Superior, Pannonia Inferior, and Noricum.

-

Roman legions and auxiliary forces focused on rebuilding and reinforcing frontier fortifications, re-establishing defensive lines, and reorganizing provincial administration.

Diplomatic Stabilization with Tribes

-

Following extensive conflict, cautious diplomatic relationships were re-established with the Marcomanni, Quadi, and Iazyges. Treaties and arrangements made by Marcus Aurelius were cautiously maintained, with adjustments reflecting new power dynamics and lingering tensions.

Continued Tribal Consolidation and Internal Changes

-

Tribal societies, impacted by warfare and disease, reorganized internally, consolidating leadership and settlements and adjusting to new Roman diplomatic realities.

Economic and Technological Developments

Gradual Economic Recovery

-

Economic recovery along the Danube frontier progressed slowly, with trade cautiously resuming between Roman provinces and tribal territories. Roman goods such as ceramics, metals, textiles, and glassware gradually re-entered circulation, exchanged for regional commodities like iron, livestock, amber, and agricultural products.

Frontier Technological and Infrastructure Improvements

-

Reconstruction of frontier fortifications stimulated localized economies and encouraged innovations in defensive architecture, military logistics, and infrastructure projects, such as improved roads, bridges, and fortresses.

Cultural and Artistic Developments

Stabilization and Resumption of Artistic Activities

-

Cultural life and artistic production gradually revived along the frontier, as reflected in pottery, metalwork, jewelry, and military equipment, exhibiting a renewed synthesis of Roman and tribal cultural influences.

Settlement and Urban Development

Reconstruction and Reinforcement of Frontier Towns

-

Roman frontier towns (Carnuntum, Vindobona, Aquincum) underwent major rebuilding and reinforcement, resuming their roles as administrative, economic, and military hubs.

-

Settlements became permanently fortified, reflecting lessons learned from earlier conflicts and anticipating potential future threats.

Tribal Settlement Adaptation

-

Germanic and Sarmatian tribal settlements adjusted to post-war conditions, establishing stronger fortifications and increasingly structured defensive communities reflecting long-term changes in settlement patterns.

Social and Religious Developments

Stabilization of Tribal Social Structures

-

After years of conflict and plague, tribal societies re-stabilized internally, further solidifying hierarchical structures dominated by warrior leaders and elites who had emerged during the wars.

Continuation and Evolution of Religious Practices

-

Religious practices among tribal groups continued to reflect themes of resilience and community solidarity, emphasizing rites that celebrated survival and protection following crisis conditions.

Long-Term Consequences and Historical Significance

The era 184–195 CE represented a critical transitional period in East Central Europe, marked by the slow but steady recovery from the devastating Marcomannic Wars and the Antonine Plague. Roman frontier provinces were rebuilt and restructured, regional economies revived, and diplomatic ties cautiously re-established, setting foundations for a renewed era of frontier stability. These efforts reshaped Roman-tribal relations and provided essential groundwork for future interactions and conflicts along the Danube frontier.

The Middle East: 184–195 CE

Continuing Religious Conflicts and Parthian Instability

From 184 to 195 CE, the Middle East experiences ongoing religious and political tensions, particularly highlighted by the lingering influence of the Montanist movement. Despite sustained opposition from Church authorities, Montanism continues to attract adherents, especially in Phrygia and other parts of Asia Minor. The movement’s persistent apocalyptic messaging and rigorous moral doctrines maintain its appeal among Christians disillusioned by the perceived moral laxity and hierarchical rigidity of the mainstream Church.

Simultaneously, political stability in the region deteriorates due to internal strife within the Parthian Empire. Succession disputes and factional rivalries weaken central authority, undermining Parthia's ability to effectively govern its vast territories. This internal instability is compounded by increased Roman interest in exploiting these divisions, as Emperor Septimius Severus, ascending to power in 193 CE, turns his ambitions toward securing Rome’s eastern borders and enhancing Roman influence in Armenia and Mesopotamia.

The interplay of religious fervor and geopolitical instability during this era underscores the complexities and shifting dynamics of power and belief in the Middle East at the close of the second century CE.

The year 193 opens in Rome with the murder of Emperor Commodus on New Year's Eve, December 31, 192 and the proclamation on New Year's Day of the City Prefect Pertinax as Emperor.

Pertinax is assassinated on March 28, 193, by the Praetorian Guard.

Didius Julianus outmaneuvers Titus Flavius Sulpicianus (Pertinax's father-in-law and also the new City Prefect) later that day for the title of Emperor.

Flavius Sulpicianus offers to pay each soldier twenty thousand sestertii to buy their loyalty (eight times their annual salary; also the same amount offered by Marcus Aurelius to secure their favors in 161).

Didius Julianus, however, offers twenty-five thousand to each soldier to win the auction and is proclaimed Emperor by the Roman Senate on March 28.

Three other prominent Romans also challenge for the throne: Pescennius Niger in Syria, Clodius Albinus in Britain, and Septimius Severus in Pannonia.

Septimius Severus marches on Rome to oust Didius Julianus and has him decapitated on June 1, 193, then dismisses the Praetorian Guard and executes the soldiers who had killed Pertinax.

Consolidating his power, Septimius Severus battles Pescennius Niger at Cyzicus and Nicaea in 193 and in 194 decisively defeats him at Issus.

Clodius Albinus initially supports Septimius Severus, believing that he will succeed him.

When he realizes in 195 that Severus has other intentions, Albinus has himself declared Emperor.

Near East (184–195 CE): Imperial Stability, Christian Scholarship, and Jewish Continuity

In the period 184–195 CE, the Near East experiences relative stability under Roman imperial rule, fostering continued growth of established religious and intellectual communities. Christianity expands quietly but steadily, gaining converts among urban populations, particularly in Alexandria, Antioch, and other cities of Asia Minor and Syria. Despite occasional local persecutions, early Christian scholars emerge, articulating theological doctrines and providing organized structures for communities.

Notably, Clement of Alexandria, active during this era, contributes significantly to the intellectual defense and expansion of Christianity. His works synthesize Christian theology with Greek philosophical thought, marking a decisive step in the integration of Hellenistic culture with Christian teachings.

In Jewish communities, the scholars (Amoraim) build upon the earlier redaction of the Mishnah, developing interpretations and commentary that will eventually be codified into the Gemara. Galilee, under continued Roman oversight, flourishes as a center of Jewish learning and cultural resilience, fostering an environment of scholarship that ensures continuity of Jewish identity and religious tradition.

At the same time, economic prosperity under Rome stimulates commerce and cultural exchange throughout the Near East, strengthening connections across the Mediterranean world.

Legacy of the Era

Between 184 and 195 CE, the Near East witnesses the deepening roots of Christianity through scholarly synthesis and community organization, alongside a thriving Jewish intellectual tradition. Both groups, despite challenges, maintain their distinct identities and religious integrity, ensuring their enduring cultural and spiritual legacies.

Mediterranean Southwest Europe (184–195 CE): Commodus’s Reign and Growing Imperial Instability

The era 184–195 CE in Mediterranean Southwest Europe marks a significant shift from the philosophical and stable rule of Marcus Aurelius to the troubled and controversial reign of his son, Commodus. This period is characterized by political instability, extravagant governance, and increasing tensions within the Roman Empire.

Ascension of Commodus and Departure from Stoicism

Commodus succeeds Marcus Aurelius in 180 CE, quickly demonstrating a stark departure from his father’s Stoic philosophy and prudent governance. His reign, beginning in his late teenage years, is marked by increasing extravagance, personal excesses, and an apparent disregard for traditional Roman virtues and senatorial authority.

Imperial Extravagance and Public Spectacles

Commodus becomes infamous for his extravagant lifestyle and obsession with gladiatorial combats. Participating personally in public spectacles, he stages elaborate gladiatorial games and wild beast hunts, aiming to bolster his popularity with the Roman masses but greatly alienating the political elite.

Political Instability and Conspiracies

Commodus’s governance fosters widespread political instability and dissatisfaction among senators and aristocrats. His reign is marked by numerous conspiracies and assassination attempts, reflecting deep-rooted discontent and weakening Rome's political cohesion.

Economic Strains and Administrative Challenges

Despite ongoing infrastructure projects and commercial activities, Commodus’s extravagant expenditures and erratic policies place increasing strain on the Roman economy. Economic stability is further undermined by administrative mismanagement and rampant corruption within the imperial bureaucracy.

Continued Cultural and Intellectual Activity

Amid political turbulence, cultural and intellectual activities persist. Artistic achievements, such as intricately carved sarcophagi and architectural developments, continue to reflect the sophistication of Roman culture. Philosophical and religious debates within early Christian communities also remain vibrant, despite Commodus’s neglect of intellectual pursuits.

Religious Developments and Christian Growth

Christian communities in Mediterranean Southwest Europe continue to expand and evolve, engaging in theological discussions and philosophical exchanges. Early Christian intellectuals actively participate in doctrinal debates, significantly shaping Christianity’s evolving identity within the Roman context.

End of Commodus’s Reign and Aftermath

The turbulent rule of Commodus ends with his assassination in 192 CE, plunging Rome into immediate political turmoil and briefly initiating a period of civil unrest. Commodus’s death ultimately highlights the vulnerability of imperial succession and the critical importance of stable governance.

Legacy of the Era

The era 184–195 CE starkly contrasts Marcus Aurelius’s thoughtful rule, demonstrating how quickly imperial stability can deteriorate under weak or extravagant leadership. The period emphasizes the fragility of Roman political cohesion, significantly influencing the future trajectory of imperial governance and setting the stage for the crises of the third century.

North Africa (184–195 CE)

Roman Stability, Urban Expansion, and Enduring Saharan Trade Networks

Roman Provincial Governance and Economic Continuity

From 184 to 195 CE, Roman administration in Africa Proconsularis continues to uphold regional stability and foster economic prosperity through consistent policies and sustained investment in infrastructure. Major urban centers such as Utica, Leptis Magna, and Caesarea (Cherchell) experience continued urban development, enhancing their critical roles in Roman Mediterranean commerce and governance.

Numidia: Economic Stability and Cultural Cohesion

Numidia maintains steady economic growth supported by Roman investments in agriculture, infrastructure, and trade networks. Numidian communities continue to integrate local traditions harmoniously within Roman administrative structures, ensuring sustained regional prosperity, social harmony, and cultural continuity.

Mauretania: Prosperity and Cultural Vibrancy

Mauretania sustains its economic vitality and cultural dynamism. The city of Caesarea remains an essential hub for extensive trade, especially in grain, olive oil, and luxury commodities, supported by ongoing Roman infrastructural enhancements. This continued economic activity underscores Mauretania’s strategic significance within Roman North Africa.

Cyrenaica: Economic Robustness and Scholarly Prestige

Cyrenaica maintains its economic strength and scholarly prominence. The Greek Pentapolis—Cyrene, Barce (Al Marj), Euhesperides (Benghazi), Teuchira (Tukrah), and Apollonia (Susah)—continues thriving commercial exchanges, particularly in grain, wine, wool, and livestock. Cyrene remains a significant intellectual hub, attracting scholars from around the Mediterranean, thus reinforcing its cultural and academic status.

Berber Communities: Economic Engagement and Cultural Resilience

Berber populations remain integral participants in regional trade, notably through coastal trade centers such as Oea (Tripoli). Inland Berber tribes maintain their traditional governance and cultural practices, benefiting from ongoing commercial prosperity along the coast. This enduring economic integration fosters regional stability and cultural continuity.

Garamantes: Continued Leadership in Saharan Trade

The Garamantes persist in their central role within trans-Saharan commerce. Through advanced agricultural practices and effective management of caravan routes, they sustain extensive trade exchanges between sub-Saharan Africa and Mediterranean markets, reinforcing regional economic stability and cultural interaction.

Mauri (Moors) and Saharan Pastoral Nomads

The Mauri (Moors) maintain their regional influence through diplomatic engagements and robust economic activities, contributing significantly to western North Africa’s ongoing stability and prosperity.

Saharan pastoral nomads continue their critical roles in facilitating trade, cultural exchange, and information dissemination across diverse ecological and economic zones, strengthening regional interconnectedness.

Cultural Syncretism and Regional Integration

Continued interactions among Berber, Roman, Greek, Garamantian, Musulami, Gaetulian, Mauri, and Saharan pastoral communities enrich regional traditions in arts, crafts, and religious practices. Vibrant religious syncretism persists, blending indigenous Berber beliefs harmoniously with Roman, Greek, Phoenician, and Saharan spiritual customs, significantly enhancing North Africa’s cultural diversity.

Foundation for Ongoing Stability and Prosperity

By 195 CE, North Africa continues to exhibit significant economic stability, cultural resilience, and regional prosperity. Effective Roman governance, consistent urban development, vibrant Berber communities, and enduring Saharan trade networks collectively underscore North Africa’s continued strategic importance within the Mediterranean geopolitical landscape.

Atlantic Southwest Europe (184–195 CE): Provincial Stability, Civic Integration, and Cultural Resilience during Commodus and the Year of the Five Emperors

Between 184 and 195 CE, Atlantic Southwest Europe—covering northern and central Portugal, Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, and northern Spain south of the Franco-Spanish border (43.05548° N, 1.22924° W)—continued to experience relative stability, economic prosperity, and cultural resilience despite the turbulent reign of Emperor Commodus (180–192 CE) and the political instability following his assassination in 192 CE (the Year of the Five Emperors, 193 CE). Throughout this politically uncertain period, provincial administration remained largely unaffected by the turmoil in Rome, with sustained economic integration, ongoing urban development, and steady civic integration through expanding Roman citizenship. Indigenous identities remained robust, creatively adapting within the stable Roman provincial structure.

Political and Military Developments

Stable Provincial Administration Amid Imperial Turmoil

-

Despite political volatility under Commodus and subsequent instability in Rome, provincial governance in Atlantic Southwest Europe remained steady and effective. Administrative continuity, supported by strong provincial bureaucracies, military garrisons, fortified urban settlements, and robust infrastructure, ensured internal peace and regional stability.

-

Local elites continued to actively integrate into Roman administrative structures, successfully insulating the region from broader imperial instability.

Ongoing Stability and Integration of Northern Tribes

-

Northern tribal regions—including the Gallaeci, Astures, and Cantabri—maintained peaceful, prosperous, and stable integration under provincial governance, benefitting economically and civically despite distant imperial unrest.

-

The Vascones continued successfully preserving their diplomatic neutrality, territorial autonomy, cultural distinctiveness, and internal stability under provincial rule.

Economic and Technological Developments

Continued Economic Prosperity and Mediterranean Integration

-

The region’s economy maintained its vitality, remaining deeply integrated within Mediterranean trade networks. Exports—valuable metals (silver, copper, tin), agricultural products, salt, timber, textiles, livestock, and slaves—continued robustly, while imports of luxury goods, fine ceramics, wine, olive oil, and sophisticated iron products reinforced local prosperity.

-

Provincial elites continued enjoying substantial economic benefits, reinforcing regional specialization, social stratification, and ongoing dependence on Roman trade.

Persistent Reliance on Slave Labor

-

Slavery remained deeply embedded in regional economic activities, particularly essential to mining, agriculture, artisanal production, domestic labor, and urban construction. The active slave trade maintained slavery’s central economic and social role.

Infrastructure Enhancement and Technological Innovation

-

Infrastructure investments continued during this period, expanding roads, aqueducts, public buildings, amphitheaters, temples, forums, bridges, and port facilities. These developments significantly improved provincial connectivity, economic efficiency, and urban amenities.

-

Technological innovations, especially in metallurgy, agriculture, and construction, continued to enhance productivity, craftsmanship, urban infrastructure, and overall regional prosperity.

Cultural and Religious Developments

Mature Cultural Integration and Artistic Flourishing

-

Material culture continued demonstrating dynamic integration of indigenous Iberian traditions, Celtic motifs, and Roman artistic influences. Intricate metalwork, jewelry, fine pottery, ceremonial objects, and household items continued to reflect resilient regional identities and cultural vitality.

-

Indigenous tribal cultures—particularly among Lusitanians, Gallaeci, Astures, Cantabri, and Vascones—remained culturally robust, creatively adapting and enriching provincial Roman society with local traditions and distinct identities.

Continued Ritual Practices and Cultural Continuity

-

Ritual traditions persisted actively, integrating indigenous Iberian, Celtic, and Roman religious elements. Sacred sites, temples, ritual landscapes, and communal ceremonies reinforced communal cohesion, cultural continuity, and local identities.

-

Traditional ancestral rites, warrior ceremonies, and local festivals endured robustly, maintaining regional solidarity, identity, and cultural resilience within the stable Roman provincial context.

Expanded Roman Citizenship and Civic Integration

-

Roman citizenship continued expanding gradually, reaching broader segments of society. Civic integration under Commodus and through subsequent political uncertainty further enhanced local identification with Roman political, civic, and cultural institutions, preparing the province for eventual universal citizenship under Caracalla’s Edict in 212 CE.

Notable Tribal Groups and Settlements

-

Lusitanians: Economically prosperous, culturally vibrant, and increasingly integrated into Roman civic structures.

-

Vettones and Vaccaei: Maintained regional prosperity, stability, and autonomy through diplomatic cooperation and civic integration.

-

Gallaeci, Astures, Cantabri: Continued stable integration into provincial governance, economically thriving while preserving local identities.

-

Vascones: Successfully maintained diplomatic neutrality, territorial autonomy, cultural distinctiveness, and internal stability.

Long-Term Significance and Legacy

Between 184 and 195 CE, Atlantic Southwest Europe:

-

Maintained remarkable provincial stability and economic vitality despite broader imperial instability, reflecting strong local governance and administrative resilience.

-

Continued economic integration into Mediterranean trade networks, deeply embedding slavery as a fundamental regional economic institution.

-

Demonstrated enduring cultural resilience and adaptive civic integration, preserving indigenous identities while progressively assimilating into broader Roman civic and cultural frameworks.

This period firmly consolidated Atlantic Southwest Europe’s historical legacy as a stable, economically prosperous, culturally resilient province within the Roman Empire, laying critical foundations for deeper integration and social transformation in subsequent decades.

Atlantic West Europe: 184–195

Between 184 and 195 CE, Atlantic West Europe—including Aquitaine, the Atlantic coast, northern and central France, Alsace, and the Low Countries—experienced increasing imperial instability under the reign of Commodus (r. 180–192), his assassination, and the subsequent "Year of the Five Emperors" (193), leading into the beginning of the Severan Dynasty under Septimius Severus. While Lyon (in Mediterranean West Europe) played a significant political role as the western base of Clodius Albinus, its influence impacted the broader stability of Atlantic West Europe during this turbulent era.Political and Military Developments

-

Reign and Fall of Commodus (184–192):

-

Commodus’s rule became increasingly erratic and oppressive, marked by corruption, administrative instability, and loss of trust among provincial elites.

-

The assassination of Commodus (December 192) threw the empire into chaos, significantly affecting provincial administration.

-

-

Year of the Five Emperors (193):

-

A succession crisis followed Commodus’s death, with multiple claimants vying for power.

-

Clodius Albinus, governor of Britannia, gained substantial support in Atlantic West Europe and established his claim in Gaul, briefly ruling as Caesar and then as Augustus, with a power base centered in Lyon.

-

-

Rise of Septimius Severus (193–195):

-

Septimius Severus emerged victorious, consolidating power after defeating rival claimants (Pescennius Niger in the east, Clodius Albinus in the west).

-

Tensions mounted in Gaul as Severus prepared for confrontation with Albinus, a conflict that deeply impacted regional stability.

-

Economic Developments

-

Instability and Economic Disruption:

-

Political instability and civil war temporarily disrupted trade networks, particularly affecting commercial centers along the Rhine and in Lyon.

-

Bordeaux's wine exports to Rome continued, but general economic uncertainty led to cautious investment and temporary decline in prosperity.

-

-

Heightened Military Expenditure:

-

Military expenses rose sharply to fund civil conflicts, increasing taxation and strain on provincial resources.

-

Urban and Rural Developments

-

Provincial Unrest and Urban Tension:

-

Lyon, as Albinus’s western capital, briefly benefited economically but also faced heightened political risk and unrest.

-

Smaller cities faced financial strain, leading to deferred civic improvements and increased local tensions.

-

-

Agricultural Stability Under Pressure:

-

Agricultural productivity largely persisted but was hampered by increased demands from military requisitions and imperial taxation.

-

Cultural and Religious Life

-

Shifts in Local Attitudes:

-

Uncertainty surrounding imperial leadership led to greater local skepticism of central authority, laying subtle foundations for increased regional identities.

-

Traditional Roman religious practices persisted, but the chaotic political environment began to foster openness to new religious movements.

-

Long-term Significance

The era (184–195 CE) was one of heightened instability and transition, marking the decline of Antonine stability and the emergence of Severan rule. These disruptions set the stage for broader provincial and imperial transformations, foreshadowing the political fragmentation and regionalism that would define later centuries in Atlantic West Europe.

Many Taoists in eastern China have begun to turn to magic and faith healing during the first century CE.

Sometime before 183, a major Taoist movement had emerged from Ji Province (modern central Hebei) -- the Taiping Sect, led by Zhang Jue (also known as Zhang Jiao), who claims he has magical powers to heal the sick.

It is said that Zhang Jue is a grandson of Zhang Daoling, founder of the Taoist sect Way of the Celestial Masters, or Way of Five Pecks of Rice (he is not, so far as is known.)

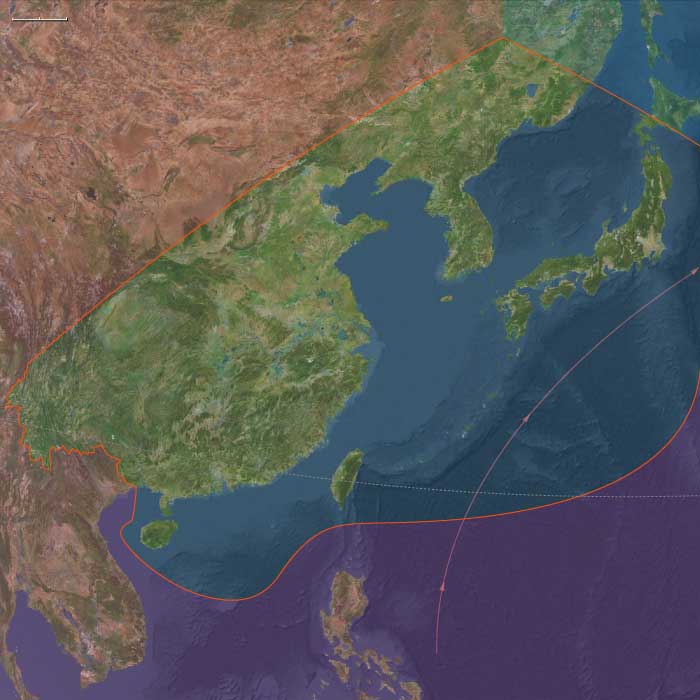

By 183, his teachings and followers had spread to eight provinces—Qing (modern central and eastern Shandong), Xu (modern northern Jiangsu and Anhui), You (modern northern Hebei, Liaoning, Beijing, and Tianjin), Ji, Jing (modern Hubei and Hunan), Yang (modern southern Jiangsu and Anhui, Jiangxi, and Zhejiang), Yan (modern western Shandong), and Yu (modern central and eastern Henan).

Several key imperial officials became concerned about Zhang's hold over his followers, and suggested that the Taiping Sect be disbanded.

Emperor Ling did not listen to them.

Zhang in fact plans a rebellion.

He commissions thirty-six military commanders and set up a shadow government, and he writes a declaration:

The blue heaven is dead.

The yellow heaven will come into being.

The year will be Jiazi.

The world would be blessed.

(Under China's traditional sexagenary cycle calendar method, the year 184 is the first year of the cycle, known as Jiazi.)

Zhang has had his supporters write Jiazi in large characters with white talc everywhere they can—including on the doors of many imperial offices in the capital Luoyang and other cities.

One of Zhang's commanders, Ma Yuanyi, enters into a plan with two powerful eunuchs, and they plan to start a rebellion to overthrow the Han Dynasty from inside.

Early in 184, this plot is discovered, and Ma is immediately arrested and executed.

Emperor Ling orders that Taiping Sect members arrested and executed, and Zhang immediately declares a rebellion.

A major cause of the rebellion is an agrarian crisis, in which famine has forced many farmers and former military settlers in the north to seek employment in the south, where large landowners exploit the labor surplus to amass large fortunes.

The situation is further aggravated by smaller floods along the lower course of the Yellow River, driving thousands of peasants from their farms; epidemics follow amid great discontent.

The peasants are further oppressed by high taxes imposed in order to fund the construction of fortifications along the Silk Road and garrisons against foreign infiltration and invasion.

In this situation, landowners, landless peasants, and unemployed former-soldiers had formed armed bands (from around 170), and eventually private armies, setting the stage for armed conflict.

At the same time, the Han Dynasty central government is weakening internally.

The power of the landowners has become a longstanding problem, but in the run-up to the rebellion, the court eunuchs in particular have gained considerably in influence over the emperor, which they abuse to enrich themselves.

Ten of the most powerful eunuchs have formed a group known as the Ten Attendants, and the emperor refers to one of them (Zhang Rang) as his "foster father".

The government is widely regarded as corrupt and incapable and the famines and floods are seen as an indication that a decadent emperor has lost his mandate of heaven.

Years: 184 - 184

Locations

People

- Cao Cao

- Gongsun Zan

- Guan Yu

- Huangfu Song

- Ling of Han

- Liu Bei

- Lu Zhi

- Zhang Fei

- Zhang Jue

- Zhao Zhong

- Zhu Jun

Groups

- Taoism

- Chinese (Han) people

- Chinese Empire, Tung (Eastern) Han Dynasty

- Way of the Five Pecks of Rice

Topics

- Han dynasty China

- Disasters of Partisan Prohibitions

- Five Pecks of Rice

- Yellow Turban Rebellion

- Liang Province Rebellion

- Three Kingdoms Period in China