East Asia (2637 – 910 BCE): Rivers, …

Years: 2637BCE - 910BCE

East Asia (2637 – 910 BCE): Rivers, Metals, and the Rise of States

Regional Overview

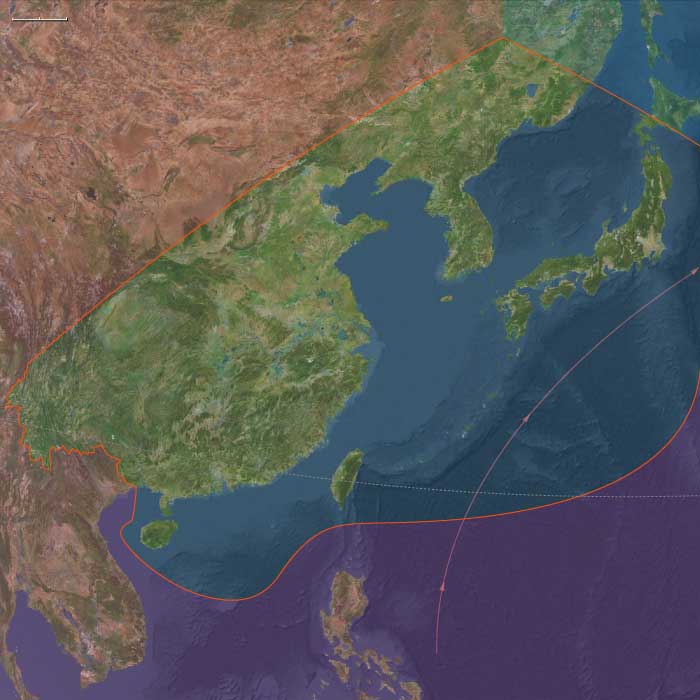

During the Bronze and Early Iron Ages, East Asia emerged as one of the world’s great civilizational heartlands.

From the Yellow and Yangtze valleys of China to the Korean Peninsula, Japan, Taiwan, and the highlands and steppe corridors of western China and Mongolia, societies transformed irrigation, metallurgy, and writing into the instruments of state power.

This was an age of hydraulic empires, bronze workshops, and expanding frontiers, when settled farmers, mobile herders, and maritime voyagers together forged the cultural matrix that would define East Asia’s classical eras.

Geography and Environment

East Asia’s vast domain encompassed temperate plains, subtropical coasts, and alpine plateaus.

The Yellow River carved loess terraces ideal for millet and wheat, while the Yangtze Delta offered lush paddies for rice.

To the north and west lay the steppe and desert margins—Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Gansu—where grasslands merged into arid basins and mountain ranges.

Along the Pacific rim, the Korean and Japanese archipelagos formed the maritime frontier, linked to the mainland by currents and trade.

These diverse settings sustained a continuum from intensive wet-rice agriculture to high-pasture nomadism.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

Holocene stability continued, though alternating floods, droughts, and cool spells along the Yellow River spurred engineering and migration.

Monsoon rains sustained southern rice fields, while drier cycles reshaped steppe pastures.

Environmental mastery—levees, canals, and paddy works—became the defining measure of political capacity.

Societies and Political Developments

By the mid-third millennium BCE, the Longshan culture of northern China had introduced walled towns and social hierarchy, evolving into the Erlitou state (often equated with the semi-legendary Xia).

The Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE) institutionalized bronze ritual, written records, and urban administration; its successor, the early Zhou, extended feudal rule across the plains.

In the south, Liangzhu and its heirs built water-managed jade-working centers.

Across the steppe rim, pastoral chiefdoms traded horses and metalwork with the settled zones, while in Korea, the Mumun culture advanced agriculture and monumental dolmen building.

The Jōmon peoples of Japan refined a maritime-forest economy, their cord-marked ceramics among the world’s oldest continuous traditions.

Economy and Technology

Agriculture anchored all development: millet and wheat in the north, rice in the south, supplemented by legumes, fruit trees, and silk production.

Bronze metallurgy reached unprecedented artistry under the Shang, producing ornate vessels, chariot fittings, and weapons.

Iron smelting appeared toward the close of this era, transforming farming and warfare.

Riverine and coastal transport expanded trade in jade, salt, ceramics, and textiles; the Yangtze Delta became a maritime hub connecting inland producers with Korea, Japan, and Taiwan.

In the west, the Hexi Corridor and Tarim oases formed early nodes of the Silk Road, moving jade eastward and horses west.

Belief, Writing, and Art

Shang oracle-bone inscriptions inaugurated Chinese writing, binding religion and administration.

Bronze vessels embodied a theology of ancestor worship and royal mediation between Heaven and Earth.

In the south, jade rituals expressed a cosmology of water and fertility; in the steppe, stone stelae and kurgan rings honored sky gods and heroic ancestors.

Across Korea and Japan, dolmens, shell mounds, and figurines encoded lineage and territorial identity.

Art and ritual thus formed a shared grammar of power from the Pacific to the Altai.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

East Asia’s civilizations grew through constant motion.

Caravan and river routes carried goods from the Tarim Basin to the Yellow Plain; maritime passages through the Bohai, East China, and Japan Seas linked coastal polities and disseminated crops, metals, and ideas.

These overlapping land and sea networks prefigured the trans-Eurasian and trans-Pacific exchange systems of later antiquity.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Flood-control levees, paddy irrigation, and terrace farming stabilized yields in volatile climates.

Nomadic mobility balanced the steppe’s shifting pastures, while coastal fishers diversified protein sources and trade goods.

In every zone, societies developed adaptive mosaics of agriculture, herding, and craft that cushioned environmental stress and underpinned political endurance.

Regional Synthesis and Long-Term Significance

By 910 BCE, East Asia was a continent of interconnected yet distinctive worlds:

-

In China, bronze states and written administration redefined governance.

-

In Korea and Japan, agrarian and megalithic cultures matured along maritime arteries.

-

In the western highlands and steppe, mobile herders linked China to Central Asia’s metallurgical frontier.

Together these traditions laid the foundations of the classical Chinese, Korean, and Japanese civilizations, and established East Asia’s lasting role as a pivot between the land empires of Eurasia and the oceanic cultures of the Pacific.

People

Groups

- Liangzhu culture

- Longshan culture

- China, archaic (Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors)

- Gojoseon (Choson)

- Sanxingdui culture

- Erlitou culture

- Chinese Kingdom, Shang Dynasty

- Chinese Kingdom, Zhou, or Chou, Western, Dynasty

Topics

Commodoties

Subjects

- Commerce

- Watercraft

- Painting and Drawing

- Labor and Service

- Decorative arts

- Government

- Custom and Law

- Technology

- Invention

- Astronomy