Northwest Asia (964 – 1107 CE): Kipchak …

Years: 964 - 1107

Northwest Asia (964 – 1107 CE): Kipchak Expansion, Kyrgyz Autonomy, and Fur–Silver Exchange

Geographic and Environmental Context

Northwest Asia includes western and central Siberia from the Ural Mountains eastward to about 130°E, embracing the Ob–Irtysh and Yenisei river systems, the West Siberian Plain, the Sayan–Altai forelands, and the Kara Sea littoral.

-

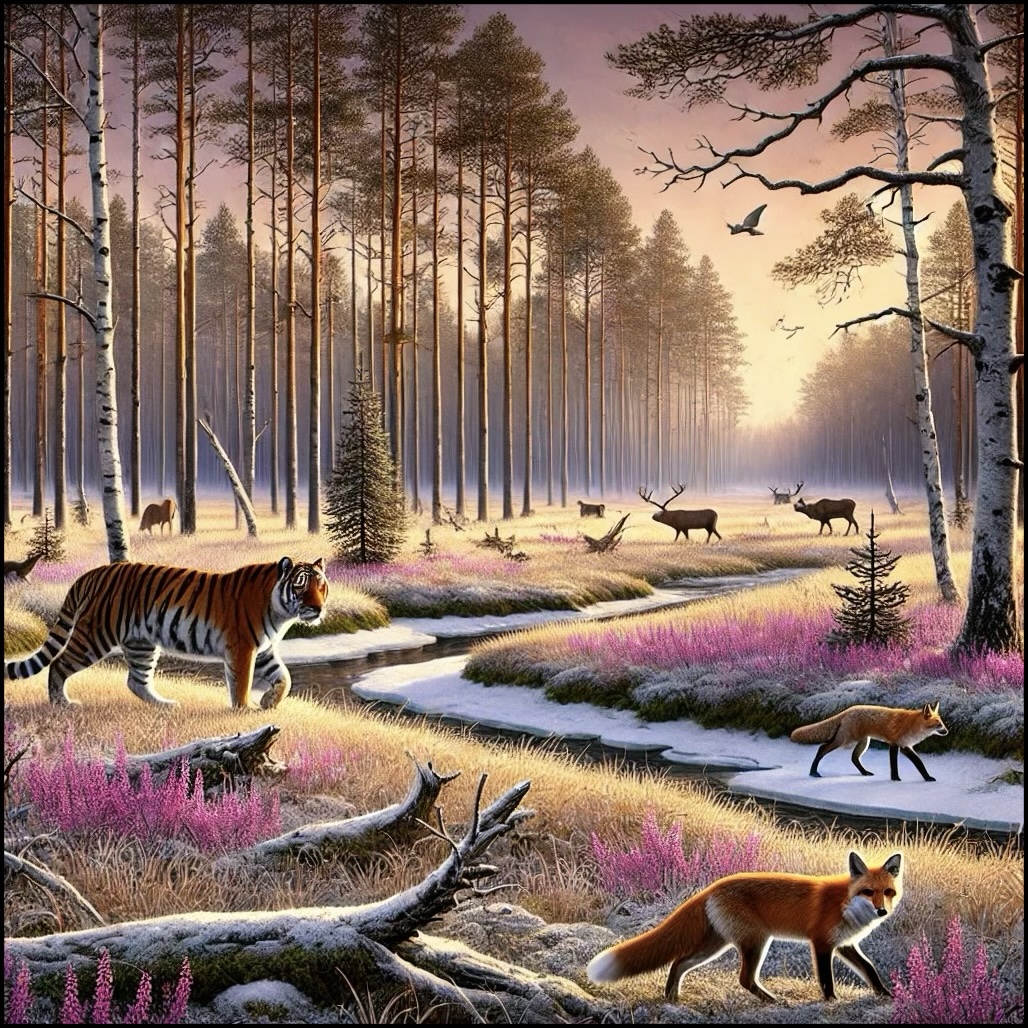

To the south, steppe–forest margins framed interaction with Turkic nomads.

-

To the north, taiga and tundra zones sustained mobile hunters, fishers, and reindeer herders.

-

The Ob, Irtysh, and Yenisei functioned as great ecological arteries, moving people, goods, and ideas between steppe, taiga, and Arctic.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

The Medieval Warm Period (c. 950–1250 CE) slightly lengthened growing and grazing seasons across southern Siberia.

-

Warmer summers improved pasture conditions for Kyrgyz and Kipchak herds and lengthened ice-free navigation windows on major rivers.

-

In the northern taiga–tundra, warming encouraged forest expansion, altering reindeer migrations and trapping zones.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Yenisei Kyrgyz:

-

After their defeat of the Uyghurs (840), the Kyrgyz retained control of the Minusinsk Basin and upper Yenisei, maintaining a khaganate with steppe cavalry and forest tribute.

-

Though less expansive than the Uyghurs, they maintained prestige in Tang and Song Chinese records, balancing autonomy with tribute diplomacy.

-

-

Forest peoples:

-

Ob-Ugric (Khanty, Mansi), Selkup, and Ket along the Ob–Irtysh; Samoyedic and Nenets on the tundra; Evenki in central taiga.

-

Kin-based clans managed fisheries, hunts, and reindeer herds, guided by shamanic ritual and seasonal councils.

-

-

Steppe frontiers:

-

The Kimek–Kipchak confederations gained strength east of the Urals and across the Ishim–Irtysh corridor.

-

By the 11th century, Kipchaks expanded westward, pressing Oghuz groups into Khwarazm and the Aral steppes.

-

These shifts deepened forest–steppe trade and spread Kipchak influence into southern Siberia.

-

Economy and Trade

-

Furs (sable, squirrel, ermine, fox, beaver) and walrus ivory remained the core export.

-

Samanid dirhams (from Transoxiana) continued to flow north via Khwarazm and Volga Bulghar, though by the late 10th century dirham output declined, leading to hack-silver economies.

-

Kipchaks and Kyrgyz traded horses, hides, and falcons for iron tools, salt, and cloth from oasis and steppe markets.

-

Forest peoples provided furs, fish oil, dried fish, antler, and wax in exchange for iron blades, copper kettles, and beads.

-

Khwarazm emerged as a key entrepôt for Ob–Irtysh furs, channeling wealth south toward Islamic markets.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Riverine fisheries: weirs, wicker traps, and netting along Ob–Yenisei; fish drying and oil rendering critical for winter.

-

Reindeer economies: Nenets and Samoyed herders expanded domestic reindeer use (sled, pack, meat, hides).

-

Hunting/trapping: elk, reindeer, beaver, sable targeted with snares and bows; pelts were wealth tokens.

-

Steppe cavalry: Kipchaks employed stirrups, lamellar armor, lances, and bows; Kyrgyz fielded similar horse-archer armies.

-

Boats & sleds: dugouts and birch-bark canoes in summer; skis, sledges, and reindeer/dog teams in winter.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Ob–Irtysh corridor: primary artery linking forest–tundra hunters to steppe traders and Khwarazm markets.

-

Yenisei corridor: Kyrgyz courts collected tribute from taiga clans, funnelling goods toward Inner Asia.

-

Urals portages: connected Khanty–Mansi fur zones to Volga–Bulghar markets.

-

Arctic coast: Kara Sea routes redistributed walrus and seal products, driftwood, and furs among Nenets and trading partners.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Forest & tundra peoples: shamanism centered on sky, river, forest, and animal spirits; bear and first-hunt rituals honored prey beings.

-

Ancestor veneration: grave goods of tools, weapons, and ornaments tied lineages to sacred landscapes.

-

Yenisei Kyrgyz: Tengri sky cult legitimated khagans; stelae and cairns marked elite burials.

-

Kipchaks: preserved shamanic rites, horse burials, and sky/earth rituals while increasingly engaging with Islam through Khwarazm intermediaries.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Mobility: clans shifted seasonally between rivers, forests, tundra, and steppe margins.

-

Portfolio subsistence: fish, game, berries, nuts, and reindeer buffered shortfalls.

-

Preservation: dried fish, smoked meat, oil caches, and fur wealth ensured winter survival.

-

Trade substitution: hack-silver, beads, and furs filled gaps as Samanid dirhams declined.

-

Alliances & tribute: Kyrgyz and Kipchaks stabilized relations with forest tribes via tribute-taking, marriage ties, and shared raiding ventures.

Long-Term Significance

By 1107 CE, Northwest Asia had become:

-

A fur frontier supplying Islamic and European markets, integrated via Khwarazm, Volga Bulghars, and Kipchak intermediaries.

-

A region of shifting steppe powers, with Kipchaks ascendant, Kyrgyz resilient but localized, and Oghuz migrating west.

-

A shamanic–animist cultural zone, resilient in ecology and ritual, yet increasingly drawn into Islamic economic circuits through silver, textiles, and tribute exchange.

This age consolidated the taiga–steppe–oasis nexus that would define Siberian history until the Mongol conquests realigned the region in the 13th century.

Northwest Asia ©2024-25 Electric Prism, Inc. All rights reserved.

Groups

- Khwarezm

- Buddhism

- Yenisei Kyrgyz

- Mansi people

- Khanty

- Volga Bulgaria, or Volga-Kama Bulgaria

- Kimek tribe

- Kimek Khanate

- Rus' Khaganate

- Samanid dynasty

- Ket people

- Nenets

- Selkup

- Evenki

- Rus' people

- Kipchaks

Topics

Commodoties

- Fish and game

- Weapons

- Hides and feathers

- Gem materials

- Glass

- Domestic animals

- Textiles

- Strategic metals

- Salt

- Manufactured goods

- Money

Subjects

- Commerce

- Symbols

- Watercraft

- Labor and Service

- Faith

- Government

- Custom and Law

- Technology

- Invention

- Metallurgy