Sknyatino, situated at the confluence of the …

Years: 1134 - 1134

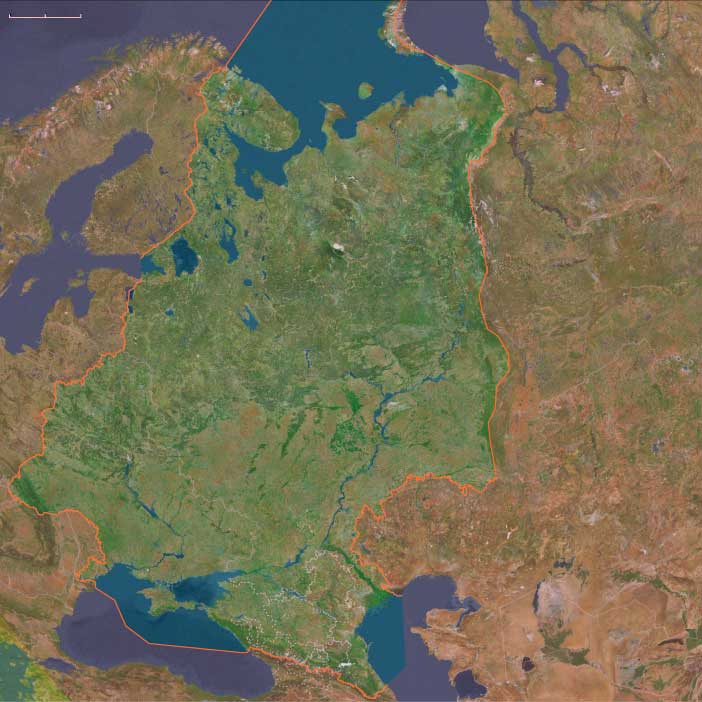

Sknyatino, situated at the confluence of the Nerl and the Volga Rivers, about halfway between Uglich and Tver, is the site of the medieval town of Ksnyatin, founded by Yuri Dolgoruki in 1134 and named after his son Constantine.

Ksnyatin is intended as a fortress to defend the Nerl waterway, leading to Yuri's residence at Pereslavl-Zalessky, against Novgorodians.

The latter will sack it on several occasions, before the Mongols virtually annihilate the settlement in 1239.

Locations

People

Groups

- Slavs, East

- Rus' people

- Novgorod, Principality of

- Kievan Rus', or Kiev, Great Principality of

- Pereslavl, Principality of

Commodoties

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 6 events out of 6 total

The Final Years and Death of Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou (1145–1151 CE)

By 1151, Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou, Duke of Normandy, and father of the future Henry II of England, had spent years consolidating his rule over Anjou, Maine, and Normandy, while dealing with baronial revolts and internal family conflicts. His reign had been marked by relentless warfare, strategic diplomacy, and an ambitious vision for the Plantagenet dynasty.

The Third Baronial Rebellion in Anjou (1145–1151)

- Between 1145 and 1151, Geoffrey faced his third major baronial rebellion in Anjou, a region known for its fractious nobility.

- The rebellion, likely fueled by resentment toward Geoffrey’s strong-handed rule and his expansion into Normandy, was a major distraction that slowed his efforts to strengthen his control over his territories.

- Geoffrey also had longstanding tensions with his younger brother, Elias, whom he imprisoned until 1151, further complicating his rule.

- The ongoing unrest in Anjou prevented Geoffrey from turning his attention to England, where his wife, Empress Matilda, was still struggling against King Stephen for the English crown.

Geoffrey’s Sudden Death (September 7, 1151)

- According to the chronicler John of Marmoutier, Geoffrey was returning from a royal council when he fell ill with a fever.

- He reached Château-du-Loir, where he collapsed on a couch, realizing that his condition was fatal.

- Before dying, Geoffrey made bequests of gifts and charities, ensuring that his religious and political obligations were fulfilled.

- He died suddenly on September 7, 1151, at the age of thirty-eight.

Burial and Legacy

- Geoffrey was buried at St. Julien’s Cathedral in Le Mans, the traditional burial site of the Counts of Anjou.

- His death marked a turning point in the struggles for Angevin power:

- His son, Henry Plantagenet (later Henry II of England), inherited Normandy, Anjou, and Maine, consolidating the foundation for the Angevin Empire.

- Henry soon crossed into England, where he would eventually claim the throne, beginning the Plantagenet dynasty’s rule over England.

Though Geoffrey never ruled England, his military conquests, political strategies, and territorial consolidations laid the groundwork for his son, Henry II, to create one of the largest realms in Western Europe—the Angevin Empire.

Attempts to Promote the Sainthood of Henry the Young King and His Funeral Procession (1183 CE)

Following the death of Henry the Young King on June 11, 1183, his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, and a faction of his friends attempted to promote his sainthood, portraying him as a penitent prince cut down in his youth. Despite his rebellion against his father, Henry II, they emphasized his acts of repentance, including his prostration before the crucifix and his request for his crusader’s cloak to be taken to the Holy Sepulchre.

A notable advocate for Henry’s sanctity was Thomas of Earley, Archdeacon of Wells, who soon after Henry’s death published a sermon describing miraculous events that supposedly occurred during the transport of his body to Normandy.

The Funeral Procession and Miraculous Accounts

Henry had left specific burial instructions:

- His entrails and other body parts were to be buried at the Abbey of Charroux.

- The rest of his body was to be laid to rest in Rouen Cathedral, the capital of Normandy.

However, his funeral did not proceed smoothly.

Difficulties During the Procession

- His mercenary captains seized a member of his household, demanding payment for debts the late prince had owed them.

- The knights accompanying his corpse were so impoverished that they had to rely on charity for food at the monastery of Vigeois.

- Wherever the procession stopped, large and emotional gatherings formed, demonstrating the people’s deep reaction to Henry’s death.

Burial at Le Mans Instead of Rouen

- Upon reaching Le Mans, the local bishop halted the procession and ordered Henry’s body buried in Le Mans Cathedral.

- This was likely a political decision, as Henry’s death had caused civil unrest, and keeping his remains in Le Mans may have been an attempt to defuse tensions in the region.

Legacy and Abandoned Efforts at Canonization

- Despite attempts to promote Henry as a saint, his reputation as a rebellious son and failed ruler prevented his canonization.

- Nevertheless, his funeral procession and reported miracles fueled legends about his piety in death, reinforcing his tragic image as a young king who never ruled.

Henry the Young King’s tumultuous life was mirrored in his death, as unpaid debts, political unrest, and miraculous tales ensured that his legacy was contested even in burial.

Richard and Philip II’s Final Campaign Against Henry II (1189 CE)

By 1189, the conflict between Henry II of England and his son Richard, Duke of Aquitaine, had reached its breaking point. After years of tensions and betrayals, Richard openly joined forces with Philip II of France, launching a final campaign to bring his father to submission.

The Franco-Scottish Army Prepares for Battle: The Campaign Leading to Verneuil (August 1424)

By August 1424, the newly reinforced Franco-Scottish army was ready to take action against the English forces of John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford. Their initial objective was to relieve the castle of Ivry, near Le Mans, which was under siege by the English. However, before they could arrive, Ivry surrendered, forcing the allied commanders to reconsider their strategy.

I. The Franco-Scottish Army Marches to Relieve Ivry

- The army was led by:

- Archibald Douglas, Earl of Douglas (now Duke of Touraine).

- John Stewart, Earl of Buchan.

- They left Tours on August 4, 1424, aiming to join forces with French commanders:

- John, Duke of Alençon.

- The Viscounts of Narbonne and Aumale.

However, before they could reach Ivry, the castle surrendered to the English, creating uncertainty over their next move.

II. The War Council: A Divided Strategy

- The allied commanders held a council of war, debating their next course of action:

- The Scots and younger French officers were eager to engage the English in battle, hoping for another decisive victory like Baugé (1421).

- The senior French nobility, led by Narbonne, remained cautious, recalling the disastrous French defeat at Agincourt (1415) and fearing another catastrophe.

- As a compromise, the allied leaders decided to target English-held fortresses along the Norman border, instead of directly confronting Bedford’s main army.

III. The Decision to Attack Verneuil

- The first target chosen was Verneuil, a key stronghold in western Normandy.

- The attack on Verneuil was intended to:

- Disrupt English control over Normandy.

- Draw Bedford’s army into a battle on favorable terms for the Franco-Scottish forces.

- This decision would lead directly to the Battle of Verneuil (August 17, 1424), a brutal confrontation that would prove to be one of the most decisive battles of the Hundred Years’ War.

IV. Consequences and the Path to Verneuil

- The decision to march on Verneuil set the stage for one of the bloodiest battles in the conflict, where the fate of the Scottish forces in France would be decided.

- The Franco-Scottish army, emboldened by previous victories, was determined to challenge English supremacy in northern France.

The march to relieve Ivry in August 1424 ended in failure, but the shift to attacking Verneuil led directly to one of the most significant battles of the war, where both Scotland and France would face their greatest test against the English under Bedford.

Death of Charles of Maine and the Angevin Legacy in France and Italy (1481)

Charles IV of Anjou, son of the Angevin prince Charles of Le Maine, inherited his father’s significant territories—including the counties of Maine, Guise, Mortain, and Gien—in 1472. Through his marriage in 1474 to Joan of Lorraine, daughter of Frederick II of Vaudémont, Charles reinforced ties between Angevin and Lorrainian interests, highlighting the interwoven dynastic politics characteristic of late medieval France.

Dynastic Ambitions and Angevin Legacy

In 1480, upon the death of his uncle, René of Anjou, Charles inherited additional territories, becoming the Duke of Anjou and Provence, as well as inheriting René’s symbolic title, Duke of Calabria, signifying Angevin claims to the Kingdom of Naples. These inherited claims placed Charles prominently within the complex power struggles over southern Italy, where Angevin ambitions had historically competed against Aragonese interests.

Testamentary Decision and Succession

Upon his death on December 10, 1481, Charles dramatically altered the geopolitical landscape through his testamentary decision to will his considerable territories—including the strategically important Duchy of Provence—to his royal cousin, Louis XI of France. This decision was historically pivotal: it decisively transferred Angevin territorial and dynastic ambitions into the French royal line, bringing Provence firmly within royal French control.

Geopolitical and Strategic Implications

Charles’s testament significantly expanded French royal power, providing Louis XI and his successors with a strategic and territorial foothold in southern France and enabling ambitious interventions in the politics of the Italian peninsula. The French monarchy thus acquired an enduring claim to Naples and Italian affairs, catalyzing future Italian military expeditions—most notably Charles VIII’s Italian campaign (1494–1498)—thereby transforming France’s international ambitions and shaping the future direction of European diplomacy.

Economic and Cultural Consequences

The inheritance of Provence and other Angevin territories not only augmented the French crown territorially but also enriched it culturally and economically. Provence, in particular, brought substantial economic benefits through its thriving Mediterranean commerce, fostering increased cultural exchange between France and Italy, and helping introduce Italian Renaissance humanist ideals into France.

Long-Term Historical Significance

Charles’s death in 1481 and his decision to transfer his inheritance directly to the French crown represented a turning point in European geopolitical history. This testament set the stage for the subsequent French invasions of Italy under Charles VIII in 1494, beginning a half-century of French involvement in Italy, profoundly shaping European power dynamics. Thus, the inheritance of Charles of Maine decisively impacted French territorial ambition, royal centralization, and the future cultural trajectory of France, placing it at the heart of European politics in the decades to come.

Robert Garnier had won two prizes in the jeux floraux, or floral games (an annual poetry contest held by the Académié des Jeux Floraux), while a law student at Toulouse,

He had published his first collection of lyrical pieces (now lost), Plaintes Amoureuses de Robert Garnier, in 1565.

After practice at the Parisian bar he became conseiller du roi in his native district, the middle Loire valley, and later lieutenant-général criminel.

Garnier's early plays—Porcie (1568), Hippolyte (1573), and Cornélie (1574)— are in the style of the Senecan school.

His next group of tragedies—Marc-Antoine (1578), La Troade (1579), and Antigone (1580)—show an advance in technique beyond the plays of Étienne Jodelle, Jacques Grévin, and his own early work, since the rhetoric is accompanied by some action.

He produces his two masterpieces, Bradamante and Les Juifves, in 1582 and 1583.

In Bradamante, the first important French tragicomedy, which alone of his plays has no chorus, he has turned from Senecan models and sought his subject in Ludovico Ariosto.

The romantic story becomes an effective drama in Garnier's hands.

Although the lovers, Bradamante and Roger, never meet on the stage, the conflict in the mind of Roger supplies a genuine dramatic interest.

Les Juifves, Garnier's second great work, is the story of the barbarous vengeance of Nebuchadnezzar on King Zedekiah and his children.

This tragedy, almost entirely elegiac in conception, is unified by the personality of the prophet.

As a Roman Catholic and a patriot, Garnier uses his tragedies to convey moral and religious arguments to his contemporaries, who are now suffering in the Wars of Religion.

His fine verse reflects the influence of his friend Pierre de Ronsard.

His plays, which contain many affecting emotional scenes, will be performed to the end of the sixteenth century.

Years: 1134 - 1134

Locations

People

Groups

- Slavs, East

- Rus' people

- Novgorod, Principality of

- Kievan Rus', or Kiev, Great Principality of

- Pereslavl, Principality of