South Atlantic (4,365 – 2,638 BCE): Late …

Years: 4365BCE - 2638BCE

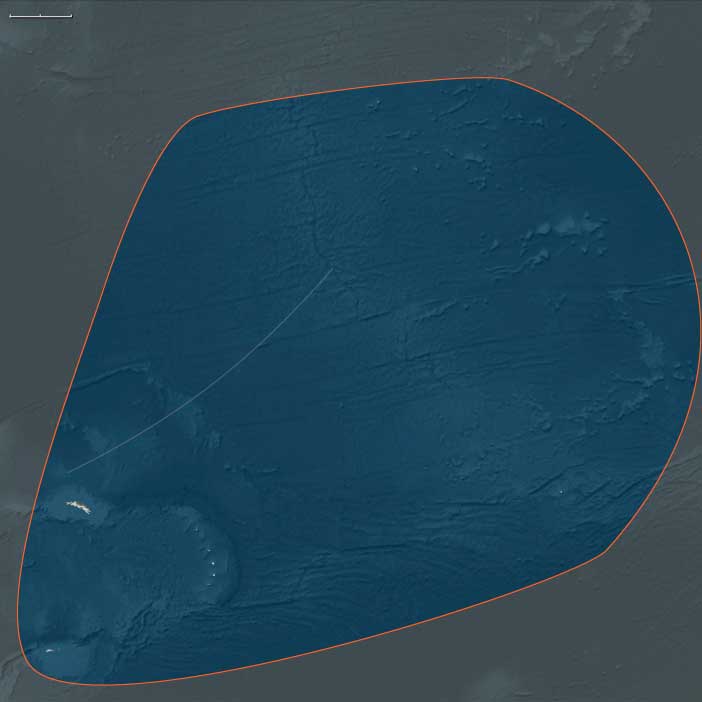

South Atlantic (4,365 – 2,638 BCE): Late Holocene — Wind Belts, Rookery Worlds, and Pelagic Engines

Geographic & Environmental Context

The South Atlantic in this epoch was a two-tier oceanic realm. To the south, subantarctic island arcs—Tristan da Cunha–Gough, Bouvet, South Georgia–South Sandwich, and the South Orkneys—rose as glaciated and tundra-fringed outposts within the westerlies and the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC). Farther north, Saint Helenaand Ascension stood in the trades, small volcanic massifs with fog-belt summits and xeric cones embedded in the South Atlantic subtropical gyre. Together they formed a continuous sea–land system in which currents, winds, shelves, and rookeries knit scattered rocks into one ecological theater.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

Mid-Holocene warmth eased toward slight late cooling. In the southern tier, seasonal sea ice advanced in winter and retreated fully in summer, opening polynyas and upwelling zones; glaciers on South Georgia and the Orkneyswaned relative to earlier millennia, widening ice-free coastal benches. Persistent westerlies drove storm trains year-round. In the northern tier, trades remained reliable; ITCZ excursions brought episodic convective rains to Saint Helena and green pulses to Ascension’s gullies. Sea level hovered near modern, stabilizing shore platforms, beaches, and kelp-edged coves.

Subsistence & Settlement

No humans were present. Ecosystems matured into self-regulating rookeries and peat–tussock mosaics:

-

Southern belt: On Tristan–Gough and ice-free pockets of South Georgia and the Orkneys, tussock grasslands, moss carpets, and cushion heaths spread on leeward benches. Penguins (king, macaroni, gentoo), albatrosses, petrels, skuas, and dense seal colonies dominated beaches and headlands; offshore, krill swarmsunderwrote whales, fish, and squid.

-

Northern belt: Saint Helena’s cloud-forest elements consolidated on summit ridges; Ascension held grass–shrub steppe with greener lee gullies. Seabirds packed cliffs; sea turtles nested on pocket beaches; moisture-trapping hollows supported diverse invertebrates.

Guano enrichment created fertility islands around colonies, accelerating plant colonization and soil building across limited terrestrial niches.

Technology & Material Culture

Contemporaneous Neolithic/Chalcolithic technologies elsewhere—ground stone, ceramics, nascent metallurgy—did not reach the South Atlantic. The region remained entirely unmodified by human hands.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Ocean and air linked every outpost. The ACC braided the southern islands into a single feeding circuit for baleen whales, penguins, and seals; frontal systems and polynyas concentrated productivity each summer. In the north, the subtropical gyre and South Equatorial current funneled tunas, billfish, and drifting turtles; seabird highwaysconnected Africa, South America, and the mid-Atlantic isles, transporting nutrients sea → land → sea. Seasonal breeding and molt cycles synchronized with ice extent, wind regimes, and upwelling windows.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

None in the human sense. The rhythmic return of whales and penguins, the greening of tussock, and the pulse of sea ice served as the region’s enduring “calendar”—a biogenic record inscribed in nesting rims, trampling paths, peat hummocks, and guano terraces.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Systems thrived by timing and flexibility. Penguins and seals selected sites by storm exposure and ice retreat; colonies shifted after rockfall or surge events. Plants quickly colonized new substrates, peatlands buffered moisture and nutrients, and krill adapted to under-ice algae cycles, sustaining higher predators through variable winters. Across both belts, life-history staggering (breeding offsets among species) and spatial redundancy (alternative ledges, benches, coves) produced durable resilience to chronic gales and episodic cooling.

Long-Term Significance

By 2,638 BCE, the South Atlantic had stabilized into a mature Holocene oceanic mosaic: storm-forged islands, robust peat–tussock terraces, vast rookeries, and pelagic food webs synchronized with winds and ice. Unseen by humans, it functioned as one of Earth’s richest marine theaters—a wind-bound biosphere whose self-maintaining cycles would persist into the cooler swings of the later Holocene, awaiting the distant arrival of seafarers and explorable shores.