Southern Australasia (964 – 1107 CE): …

Years: 964 - 1107

Southern Australasia (964 – 1107 CE):

Aquaculture Flourishing, Fire-Managed Ecologies, and Isolated Refuges

Geographic and Environmental Context

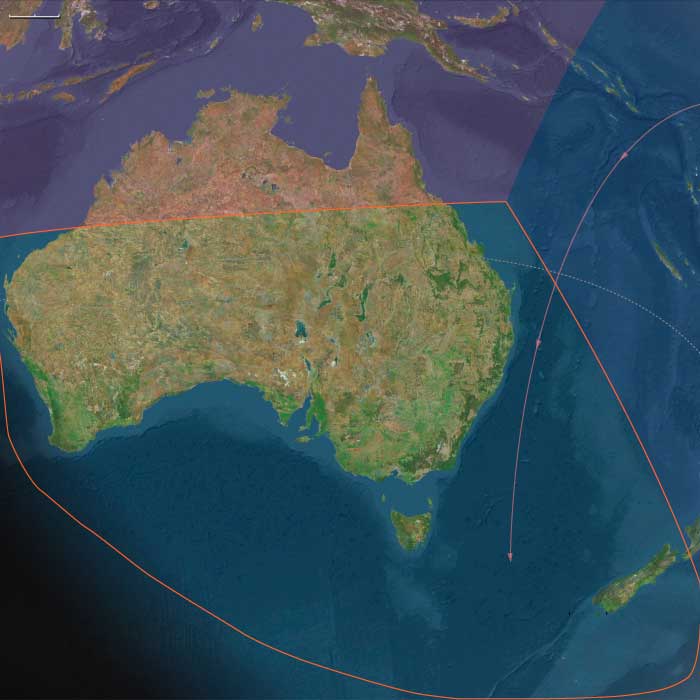

Southern Australasia includes central and southern Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand’s South Island, the southwestern coast of the North Island, and the subantarctic islands (Stewart, Auckland, Campbell, Antipodes, Bounty, and Snares).

-

In Australia, Aboriginal nations engineered wetlands, plains, and fire mosaics for sustainable productivity.

-

In Tasmania, the Palawa maintained seasonal hunting and fishing circuits.

-

New Zealand and subantarctic islands remained uninhabited, dominated by seabirds and flightless fauna.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The Medieval Warm Period produced mild stability punctuated by regional wet–dry oscillations.

Fire-knowledge and controlled burning in southern Australia maintained ecological balance; subantarctic islands remained storm-bound refuges for marine life.

Societies and Political Developments

Southern Australian kinship nations—Gunditjmara, Yorta Yorta, Ngarrindjeri, Noongar, Palawa, and others—upheld songline law binding spiritual and ecological stewardship.

-

Budj Bim eel aquaculture sustained semi-sedentary communities.

-

Palawa clans rotated through coasts, plains, and uplands in seasonal rhythms.

-

New Zealand and the subantarctic islands remained beyond human reach.

Economy and Trade

-

Budj Bim wetlands: surplus smoked eel traded widely.

-

Riverine fish traps along the Murray–Darling and Coorong harvested seasonal runs.

-

Exchange networks conveyed ocher, stone, shells, wood, and ceremonial goods across southeastern Australia.

-

Tasmania: shell necklaces and ocher circulated among clans.

Elsewhere, ecosystems continued undisturbed.

Subsistence and Technology

Broad-spectrum foraging combined with hydraulic engineering:

stone ponds, eel races, and fish weirs enhanced yields.

Fire regimes expanded grasslands for macropods and tubers.

Toolkits included ground-edge axes, woomeras, nets, digging sticks, and ocher paints; in Tasmania, bone tools and reed rafts supported mobility.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

The Murray–Darling basin formed the core of inter-group ceremony.

Coastal routes and island crossings facilitated shell and food exchange.

New Zealand’s South Island and the subantarctic islands remained pristine ecological zones.

Belief and Symbolism

Dreaming stories codified ecological law across the landscape.

Ceremonial grounds—rock engravings, dance circles—marked sacred geography.

The Budj Bim eel Dreaming tied aquaculture to ancestral creation.

Palawa rituals honored sea and land as ancestral gifts.

Adaptation and Resilience

Diversified diets and managed burning buffered climate variability.

Redistributive ceremonies promoted cooperation after scarcity.

Uninhabited islands preserved pre-human ecosystems that would later be reshaped by migration.

Long-Term Significance

By 1107 CE, Southern Australasia exemplified human–ecological harmony through aquaculture and fire-management, while New Zealand and subantarctic islands stood untouched.

These lands formed both a cultural heart of resilience and an ecological frontier soon to enter human history.