Western West Indies (1684–1827 CE): Sugar Kingdoms, …

Years: 1684 - 1827

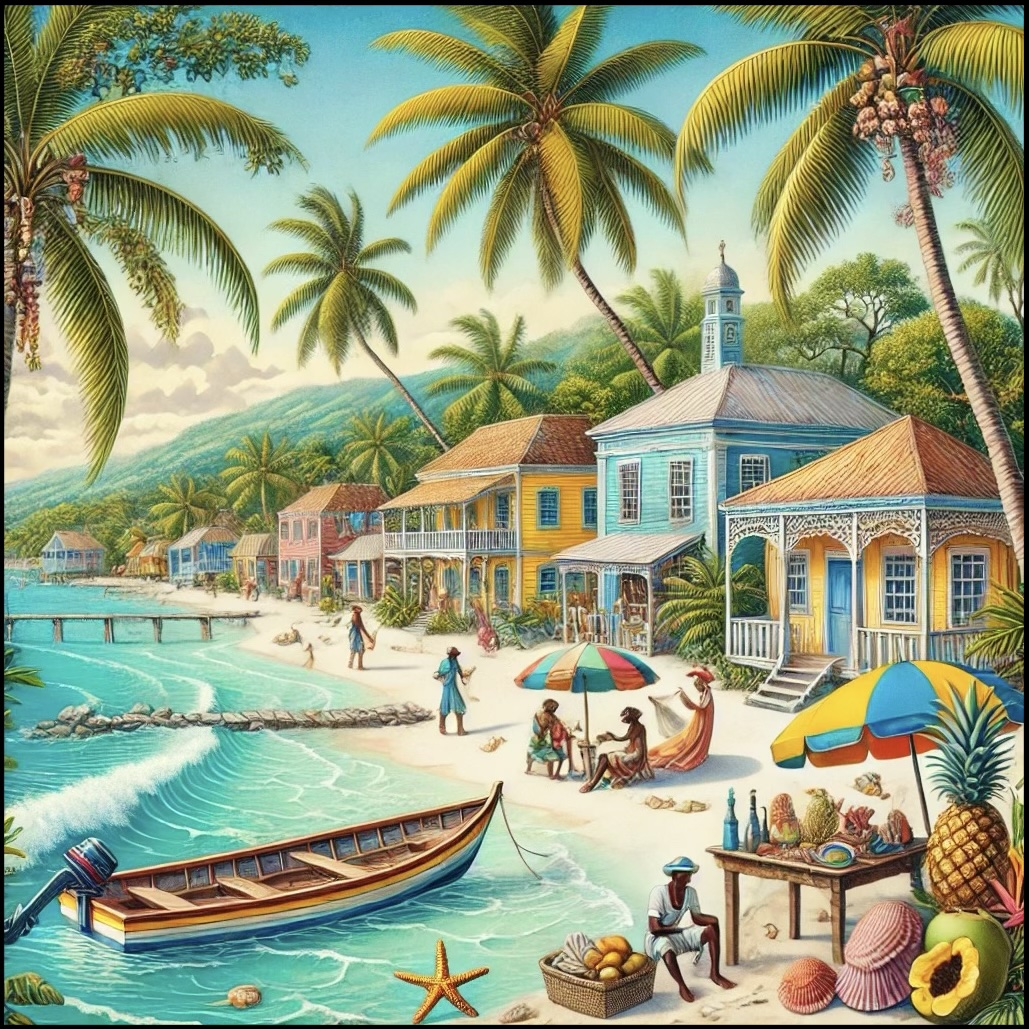

Western West Indies (1684–1827 CE): Sugar Kingdoms, Slave Resistance, and Imperial Rivalries

Geographic & Environmental Context

The subregion of Western West Indies includes Cuba, Jamaica, the Cayman Islands, and the Inner Bahamas (Andros, New Providence, Great Exuma, and neighboring islands). Anchors included Havana harbor, the Blue Mountains of Jamaica, the Andros Barrier Reef, and the Cayman Trench. The subregion’s fertile soils, deepwater ports, and strategic channels made it the focus of imperial competition between Spain and Britain.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The late Little Ice Age lingered into the 18th century. Hurricanes devastated Jamaica (1722, 1780) and Cuba (1768, 1791). Droughts occasionally affected plantations, but warm, humid conditions generally sustained sugar, tobacco, and coffee. The Bahamas remained vulnerable to storms and shallow soils, while the Caymans supported small-scale settlement around turtle fisheries.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Cuba: Became Spain’s wealthiest colony. Havana was fortified as a naval hub. Vast sugar and tobacco plantations expanded, powered by enslaved Africans. Coffee planting spread in the late 18th century.

-

Jamaica: Seized by England in 1655, Jamaica grew into a leading sugar producer. Plantations dominated the coastal plains, with enslaved Africans forming the majority. Maroon communities in the mountains resisted colonial control, negotiating treaties in 1739.

-

Bahamas: Nassau developed into a British colonial capital after piracy was suppressed by Governor Woodes Rogers in 1718. Loyalist refugees after the American Revolution brought enslaved Africans, expanding plantations on the larger islands.

-

Cayman Islands: Remained lightly settled by English families, focused on turtle hunting, fishing, and small-scale plantations using enslaved labor.

Technology & Material Culture

Plantation technology—sugar mills, boiling houses, and windmills—defined landscapes. Africans preserved traditions in food, crafts, and music, blending them with European and Indigenous survivals. British fortifications in Nassau and Port Royal, and Spanish bastions in Havana, embodied imperial rivalry. Bermuda sloops and other fast vessels linked ports with Atlantic markets.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Atlantic slave trade brought tens of thousands of Africans into Cuba and Jamaica.

-

Spanish treasure fleets still rallied at Havana into the 18th century.

-

British convoys linked Jamaica and the Bahamas to London and North America.

-

Maroon trails in Jamaica tied mountain refuges to coastlines.

-

Smuggling flourished between Cuba and Saint-Domingue, later Haiti.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Catholicism remained dominant in Cuba, infused with African spiritual traditions such as Regla de Ocha(Santería).

-

Protestant Anglicanism anchored Jamaica and the Bahamas, though African-derived religions and rituals survived in plantations and Maroon villages.

-

Music, drumming, and oral epics carried memory and defiance.

-

Festivals, carnivals, and saints’ days blended African, European, and Indigenous traditions.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Planters shifted between sugar, coffee, and tobacco to balance markets. Africans adapted resilience through food plots, kinship networks, and ritual practice. Maroons maintained independence in difficult mountain environments. Coastal towns rebuilt after hurricanes, while sailors and fishers of the Caymans relied on provisioning voyages.

Transition

By 1827 CE, the Western West Indies was marked by deep contrasts: Cuba remained Spain’s “Pearl of the Antilles,” reliant on slavery and plantations, while Jamaica stood as Britain’s sugar jewel, though plagued by resistance and unrest. The Bahamas stabilized under British colonial rule but faced fragile soils and dependence on trade. The Caymans lingered on the margins as small maritime outposts. Across the subregion, African labor, culture, and resistance defined daily life, and the region had become one of the most contested and productive corners of the Atlantic world.

Western West Indies (with civilization) ©2024-25 Electric Prism, Inc. All rights reserved.

People

Groups

Topics

Commodoties

Subjects

- Commerce

- Symbols

- Sculpture

- Decorative arts

- Games and Sports

- Faith

- Government

- Custom and Law

- Mythology