Zhang Bu, nominally the Prince of Qi …

Years: 29 - 29

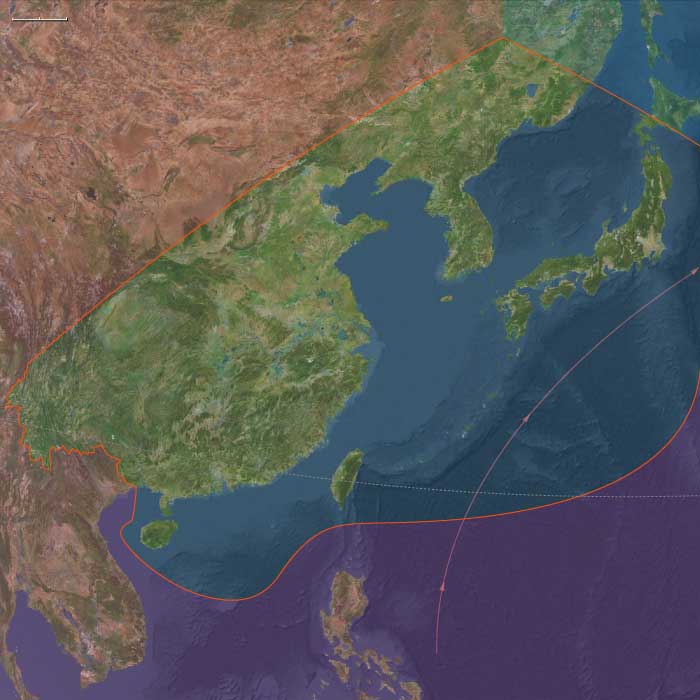

Zhang Bu, nominally the Prince of Qi under Liu Yong, independently controls the modern Shandong region.

Seeing the futility of resistance, Zhang surrenders and is created a marquess.

Locations

People

Groups

Topics

Commodoties

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 30 total

Armenia, after contact with centers of early Christianity at Antioch and Edessa, accepts Christianity as its state religion in 306 (the traditional date—the actual date may have been as late as 314), following miracles said to have been performed by Saint Gregory the Illuminator, son of a Parthian nobleman.

Thus Armenians claim that Tiridates III (238- 314) was the first ruler to officially Christianize his people, his conversion predating the conventional date (312) of Constantine the Great's legalization of Christianity on behalf of the Roman Empire.

The Middle East: 376–387 CE

Imperial Struggles and Renewed Roman–Sassanid Tensions

The period 376 to 387 CE witnesses renewed geopolitical tensions and strategic realignments in the Middle East, marking another chapter in the enduring rivalry between the Roman Empire and the Sassanid Persians. While previously established diplomatic accords between Emperor Valens and King Shapur II had provided a temporary respite, the late fourth century again sees escalating friction as both powers seek to extend influence and consolidate control over contested territories, notably Armenia and Mesopotamia.

The death of Shapur II in 379 CE, after a long and vigorous reign, leads to a brief period of internal instability within the Persian Empire. His successors, Ardashir II (379–383 CE) and Shapur III (383–388 CE), face internal challenges, including court intrigues and regional rebellions, limiting Persia’s immediate ability to capitalize on Roman distractions elsewhere.

On the Roman side, the disastrous defeat at Adrianople in 378 CE, in which Emperor Valens is killed, diverts Roman military resources to the northern frontier to counter Gothic incursions. This crisis compels Emperor Theodosius I (379–395 CE) to seek diplomatic solutions rather than prolonged warfare with Persia. Armenia, the perennial focal point of rivalry, is once again partitioned in 387 CE through the diplomatic initiative known as the Peace of Acilisene, with Rome and Persia agreeing to divide the kingdom along a negotiated boundary. The western portion of Armenia falls under Roman influence, while Persia secures the larger, strategically significant eastern region.

Culturally, this era remains a vibrant period of religious and intellectual consolidation in the Middle East. Christianity further solidifies its presence within the Roman sphere, strengthening its ecclesiastical institutions and establishing theological foundations that significantly influence both eastern and western Christendom. Meanwhile, Persia maintains its tradition of religious pluralism, with Zoroastrianism flourishing alongside Jewish and emerging Christian communities.

The Peace of Acilisene thus represents a pivotal diplomatic achievement, temporarily stabilizing the eastern frontier. However, the division of Armenia underscores a persistent geopolitical rivalry that will continue to shape regional dynamics for centuries to come.

The compromise peace with the Persians concluded in 387 gives Rome a small section of Armenia, where the emperor founds Theodosiopolis (Erzurum)

The Persians had been forced by Diocletian to relinquish Armenia, and Tiridates III, the son of Tiridates II, had in about 287 been restored to the throne under Roman protection; his reign had determined the course of much of Armenia's subsequent history, and his conversion by St. Gregory the Illuminator and the adoption of Christianity as the state religion (c. 314) has created a permanent gulf between Armenia and Persia.

Saint Mesrop, also known as Mashtots, devises an alphabet for the Armenian language early in the fifth century CE, and religious and historical works begin to appear as part of the effort to consolidate the influence of Christianity.

For the next two centuries, political unrest will parallel the exceptional development of literary and religious life that becomes known as the first golden age of Armenia.

The Middle East: 388–399 CE

Stability and Religious Consolidation

The period from 388 to 399 CE in the Middle East is characterized primarily by a temporary stabilization of geopolitical tensions between the Roman and Sassanid Empires following the significant Peace of Acilisene in 387 CE. This agreement, which divides Armenia into distinct Roman and Persian spheres of influence, ushers in a brief phase of diplomatic calm, allowing both empires to consolidate their control and focus internally.

Armenian Division and Regional Stability

Armenia, previously a focal point of Roman–Persian rivalry, is now officially partitioned between Rome and Persia. The Roman-controlled west and the Sassanian-dominated east coexist under a pragmatic arrangement that significantly reduces regional tensions. This division helps maintain a fragile peace that will endure for some decades, stabilizing the volatile Caucasian frontier.

Expansion and Strengthening of Christianity

Christianity continues its expansive growth during this era, further solidifying its influence in regional politics and culture. Armenia, under Roman influence, remains committed to Christianity, deepening its religious and cultural ties to Byzantium. Similarly, Christianity further entrenches itself in Georgia, bolstered by the earlier conversion under King Mirian III. These Christian communities continue to develop distinctive traditions, which will profoundly shape their national identities.

Persian Religious and Cultural Consolidation

Within the Sassanid Empire, the Zoroastrian priesthood continues to hold significant influence, reinforcing the empire's internal stability through strict social and religious structures. The Persian authorities intensify their efforts to promote Zoroastrian beliefs and Persian cultural norms across their territories, particularly within the Persian Gulf region, maintaining the agricultural colonies and strategic arrangements with local tribes established previously.

Economic and Urban Prosperity

Greater Syria, under Roman governance, experiences continued economic prosperity and urban development. Important trade centers such as Damascus, Palmyra, and Busra ash Sham thrive due to well-established infrastructure and effective administrative practices. The sustained economic vitality of these cities reinforces the Roman administrative efficiency established by Emperor Constantine, with Syria continuing to serve as a crucial economic and cultural bridge between East and West.

Thus, the era from 388 to 399 CE in the Middle East represents a brief but critical interlude of geopolitical calm and internal consolidation, laying a stable foundation for the transformative developments of subsequent decades.

Armenia during the reign of Shapur III had been divided between the Roman and Persian empires according to the terms of a peace treaty, but this arrangement has barely survived his reign.

Khosrov III, the Arsacid King of Armenia under Persian suzerainty, has by about 390 grown wary of his subordination to Persia and entered into a treaty with the Roman Emperor Theodosius who in return for this allegiance had deposed Arshak III in Roman Armenia and made Khosrov the king of a united Armenia.

Enraged, Bahram IV takes Khosrov prisoner in 392 and confines him to the Castle of Oblivion, placing his brother Varahran-Shapur upon the Armenian throne.

Khosrov appeals to Theodosius for help but the latter refuses to intervene, as it would constitute a breach of the peace of 384.

The Middle East: 400–411 CE

Renewed Tensions and Religious Dynamics

The period from 400 to 411 CE sees the fragile stability achieved by the earlier Peace of Acilisene begin to erode, leading to renewed tensions between the Roman (Byzantine) and Sassanid Empires. Although no full-scale war erupts immediately, mutual suspicion and border skirmishes become increasingly frequent, especially along the contested territories of Armenia and Mesopotamia.

Armenia as a Flashpoint

The divided Armenia continues to be a significant point of friction. Roman control in the west remains relatively stable, supported by strong cultural and religious ties to Christianity, which deepen Armenia's alignment with Byzantium. Conversely, Sassanian-controlled eastern Armenia endures intensified Persian cultural and religious influence, emphasizing Zoroastrian orthodoxy and Persian administrative methods. The cultural and religious divergence between these two regions deepens, highlighting Armenia's role as a persistent geopolitical flashpoint.

Christianity's Institutional Growth

Christianity continues its robust institutional development in the Roman territories, shaping regional identities and governance structures. The influence of prominent religious figures, particularly bishops and theologians, expands considerably, consolidating Christian doctrinal authority. Churches and monasteries flourish, becoming not only centers of worship but also vital hubs for education, manuscript preservation, and social services.

Zoroastrian Orthodoxy and Persian Governance

In the Sassanian Empire, the Zoroastrian priesthood's influence grows further under state sponsorship, playing an integral role in governance and social regulation. Religious authorities closely align with the imperial administration to ensure social conformity and stability, reinforcing Persian identity throughout the empire. This period witnesses an increased emphasis on reinforcing traditional Iranian culture and Zoroastrian practices across Persian-held territories.

Economic Continuity and Urban Development

Greater Syria, despite geopolitical uncertainties, maintains considerable economic prosperity under Roman administration. Major cities such as Damascus, Palmyra, and Busra ash Sham continue to thrive, benefiting from established trade routes and robust infrastructure. These cities reinforce their roles as vibrant commercial and cultural centers, fostering continued urban growth and economic stability in the region.

Thus, the era from 400 to 411 CE is characterized by a precarious balance between escalating geopolitical tensions and vigorous religious and economic developments, setting the stage for significant future transformations in the Middle East.

The Middle East: 412–423 CE

Cultural and Religious Flourishing

Between 412 and 423 CE, the Middle East experiences vibrant cultural and religious development despite ongoing geopolitical tensions. In particular, the Jewish communities of Babylonia and Palestine significantly enrich their religious and cultural life. This period witnesses the compilation and embellishment of the Jewish Hagadah texts, which complement the ethical and theological discourses of the Talmud with lively anecdotes, legends, and illustrative stories. These texts become central to Jewish religious study, providing moral instruction and fostering cultural cohesion across dispersed Jewish communities.

Continued Roman–Sassanian Tensions

Although no major wars erupt during this era, friction between the Roman (Byzantine) and Sassanid Empirespersists, particularly along their shared border regions in Armenia and Mesopotamia. Frequent small-scale clashes and mutual provocations maintain a climate of tension, highlighting the strategic importance and ongoing volatility of these contested areas.

Religious Institutions and Authority

Within Roman-held territories, the institutional influence of Christianity continues to expand, driven by prominent bishops and theologians who further consolidate doctrinal authority and ecclesiastical power. Churches and monasteries serve as critical centers of education, manuscript preservation, and community support, strengthening Christian cultural identity across the region.

Zoroastrian Consolidation

In the Sassanian Empire, the integration of Zoroastrian orthodoxy within Persian governance structures advances significantly. The state-supported priesthood deepens its role in societal regulation and governance, reinforcing traditional Iranian identity and maintaining cultural unity throughout Persian-controlled territories.

Economic Stability and Urban Vitality

Cities such as Damascus, Palmyra, and Busra ash Sham under Roman rule continue their economic and cultural flourishing. Robust trade routes and strong infrastructure support ongoing prosperity, enabling these urban centers to sustain their significance as vibrant commercial and cultural hubs.

Thus, the years 412 to 423 CE mark an era of significant religious, cultural, and economic dynamism, even as geopolitical tensions between the major regional powers persist, shaping the future trajectory of the Middle East.

The Middle East: 424–435 CE

Armenia: Cultural Flourishing Amid Political Change

Between 424 and 435 CE, Armenia undergoes significant political and cultural transformations. Following Armenia’s earlier division in 387 CE into Roman Armenia and Persarmenia, the region continues to experience divergent trajectories under Roman and Persian influences. Roman Armenia, roughly one-fifth of the original territory, is quickly integrated into the Roman (Byzantine) Empire, contributing significantly to its military and political leadership.

Persarmenia remains under nominal Arsacid rule until 428 CE, when King Artashes IV is deposed at the behest of the powerful Armenian noble class, known as the nakharars, and replaced by a Persian governor (marzpan). This change effectively ends Armenia’s political sovereignty. However, the loss of political independence spurs a cultural renaissance that profoundly shapes Armenian identity.

Rise of Armenian National Identity

Central to this cultural resurgence is the development of the Armenian alphabet and the flourishing of national Christian literature, achievements largely attributed to the monk Mesrop Mashtots and his collaborators. These advancements fortify a distinct Armenian cultural and religious identity, fostering unity and resilience despite political subjugation.

The earlier conversion of Armenia to Christianity under King Tiridates III and Saint Gregory the Illuminator (circa 314 CE) continues to exert a profound influence, firmly entrenching Christianity as a cornerstone of national identity. The Armenian Church, led by the patriarchate, assumes a pivotal role in preserving national cohesion and culture in the absence of political autonomy.

Roman–Sassanian Rivalries

Simultaneously, persistent tensions between the Roman (Byzantine) and Sassanian Empires continue along the contested borders of Armenia and Mesopotamia. Although large-scale conflict is relatively restrained during this period, frequent border skirmishes and diplomatic disputes underline the volatile and strategically critical nature of this frontier.

Continued Urban Prosperity and Religious Institutions

In Roman-controlled Syria, cities such as Damascus, Palmyra, and Busra ash Sham remain vibrant centers of commerce, culture, and learning. The period sees ongoing economic stability supported by robust trade networks and infrastructure, further solidifying these urban centers as hubs of regional influence.

Meanwhile, the consolidation of Zoroastrian orthodoxy continues within the Sassanian Empire, reinforcing cultural identity and social cohesion under Persian rule. The Zoroastrian priesthood remains influential, contributing significantly to the governance and societal structure of Persian-controlled territories.

Thus, the era 424 to 435 CE in the Middle East marks an epoch of critical political realignment, profound cultural renaissance in Armenia, and ongoing geopolitical tension, setting the stage for subsequent historical developments in the region.

Diocletian had forced the Persians to relinquish Armenia, and Tiridates III, the son of Tiridates II, had been restored to the throne under Roman protection in about 287; his reign had determined the course of much of Armenia's subsequent history, and his conversion by St. Gregory the Illuminator and the adoption of Christianity as the state religion in about 314 has created a permanent gulf between Armenia and Persia.

The Armenian patriarchate becomes one of the surest stays of the Arsacid monarchy and the guardian of national unity after its fall.

The chiefs of Armenian clans, called nakharars, hold great power in Armenia, limiting and threatening the influence of the king.

The dissatisfaction of the nakharars with Arshak II had led to the division of Armenia into two sections, Roman Armenia and Persarmenia, in 387).

The former, comprising about one-fifth of Armenia, had been rapidly absorbed into the Empire, to which the Armenians will come to contribute many emperors and generals.

Persarmenia continues to be ruled by an Arsacid in Dvin, the capital after the reign of Khosrow II (330–339), until the deposition in 428 of Artashes IV and his replacement by a Persian marzpan (governor) at the request of the nakharars.

Although the Armenian nobles have thus destroyed their country's sovereignty, a sense of national unity will be furthered by the development of an Armenian alphabet and a national Christian literature; culturally, if not politically, the fifth century is an Armenian golden age.