Bertrand-François Mahé de La Bourdonnais

French naval officer and administrator, in the service of the French East India Company

Years: 1699 - 1753

Bertrand-François Mahé, comte de La Bourdonnais (February 11, 1699 – November 10, 1753) was a French naval officer and administrator, in the service of the French East India Company.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 6 events out of 6 total

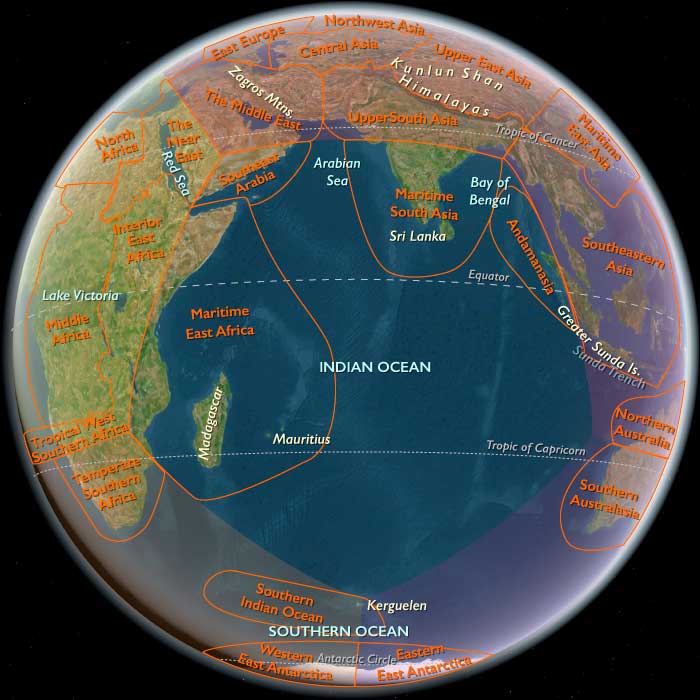

Maritime East Africa (1684–1827 CE): Omani Ascendancy, Malagasy Kingdoms, and Island Crossroads

Geographic & Environmental Context

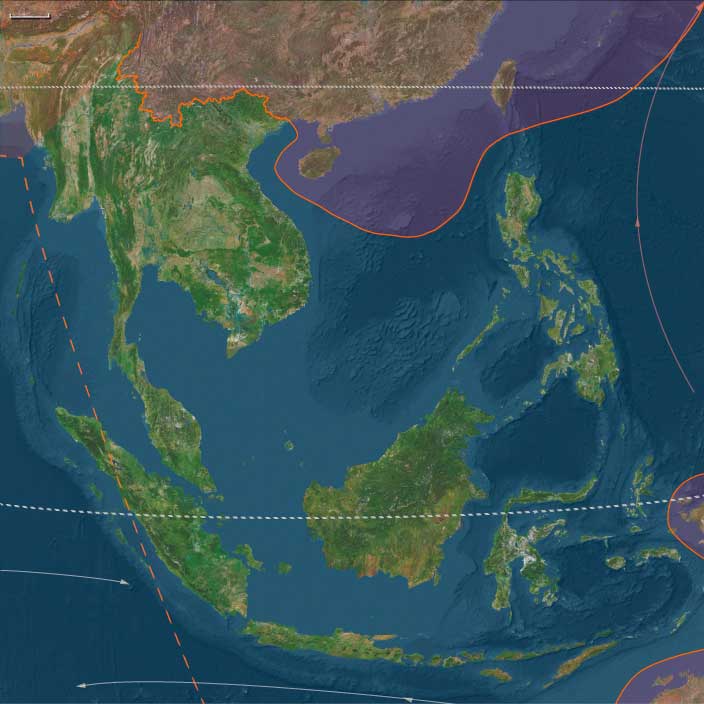

The subregion of Maritime East Africa includes Somalia, eastern Ethiopia, eastern Kenya, eastern Tanzania and its islands, northern Mozambique, the Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, and Seychelles. Anchors included the Swahili port cities (Mombasa, Zanzibar, Kilwa, Sofala, Mogadishu), the offshore islands of Zanzibar, Pemba, and the Comoros, the highlands and rice terraces of Madagascar, and the outlying islands of Mauritius and Seychelles.During this period, Portuguese coastal dominance receded and Omani Arabs asserted control, reshaping trade and political authority across the Indian Ocean rim.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The waning Little Ice Age produced cycles of drought and flood. Pastoral Horn communities faced grazing crises; coastal farmers diversified subsistence with cassava, maize, and bananas. Madagascar experienced alternating famine and abundance: drought struck southern regions, while the highlands expanded irrigated rice. Cyclones occasionally battered the Comoros, Mauritius, and Seychelles.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Swahili towns: Retained Islamic, mercantile character; hinterland caravans carried ivory, slaves, and gold. Cassava and maize, by now entrenched, expanded diets.

-

Zanzibar and Pemba: Grew coconuts, rice, and cloves (clove plantations expanded in the early 19th century under Omani rule). Fishing and trade supported islanders.

-

Comoros: Balanced subsistence gardens, rice paddies, fishing, and inter-island commerce; communities rebuilt repeatedly after cyclones.

-

Madagascar: Merina kingdom in the central highlands expanded under Andrianampoinimerina (r. c. 1787–1810), consolidating rice terraces, tribute systems, and iron-armed armies. The Sakalava maintained coastal cattle-based polities, raiding for slaves.

-

Mauritius and Seychelles: Colonized by the French in the 18th century; developed sugar plantations using enslaved labor.

Technology & Material Culture

Swahili towns featured coral-stone mosques, minarets, and merchant houses with carved doors. Dhows with lateen sails carried regional cargoes. Firearms, imported via Omani and European trade, armed coastal and Malagasy polities. On Madagascar, rice irrigation systems, cattle corrals, and fortified hilltop villages symbolized power. French colonists built sugar mills on Mauritius; Seychellois settlers planted coconuts and food gardens.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Omani ascendancy: By the late 17th century, Oman expelled Portugal from Mombasa (1698) and gradually claimed authority over Swahili ports, consolidating Zanzibar as a capital of Indian Ocean commerce.

-

Ivory and slave caravans: Moved inland from Tanzania and Mozambique toward coastal entrepôts, feeding growing Omani and French demand.

-

Madagascar: Exported slaves and cattle to the Mascarenes and Swahili coast; imported textiles, firearms, and beads.

-

Comoros: Functioned as provisioning islands for dhows, slavers, and European ships rounding the Cape.

-

Mauritius and Seychelles: Integrated into the French colonial empire as plantation colonies, with enslaved Africans imported from Mozambique and Madagascar.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Islam remained central to Swahili towns: mosques, madrasas, and Arabic-script poetry thrived. Omani authority patronized Islamic judges and scholars. On Madagascar, ancestor veneration, tomb construction, and cattle rituals anchored Merina and Sakalava legitimacy; Merina rulers combined ritual kingship with bureaucratic tribute. The Comoros developed Islamic scholarship blended with local ritual. In the Mascarenes, French Catholicism, African traditions, and creole cultures fused in plantation societies.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Coastal and island farmers diversified crops—cassava, maize, bananas—buffering drought. Highland Merina expanded rice terraces to secure food supplies. Sakalava herders maintained cattle herds across shifting pastures. Island societies rebuilt after cyclones, replanting coconuts and rice paddies. Plantation colonies relied on enslaved labor for resilience, but suffered when storms or droughts disrupted supply lines.

Technology & Power Shifts (Conflict Dynamics)

Portuguese forts weakened as Oman asserted dominance; cannon and ships secured Zanzibar and Mombasa. Omani sultans organized tribute and port governance, tying the coast to Muscat. Slave and ivory raiding expanded inland, destabilizing societies in Tanzania, Mozambique, and Madagascar. The Merina kingdom grew into a centralized power, conquering neighbors with firearms and reorganizing tribute. In the Mascarenes, French planters entrenched slavery; enslaved resistance and marronage persisted.

Transition

By 1827 CE, Maritime East Africa had entered a new era. Omani Zanzibar dominated the Swahili coast, dispatching dhows across the Indian Ocean. Madagascar saw the rise of the powerful Merina kingdom, while coastal Sakalava still controlled raiding zones. The Comoros remained small but strategic. Mauritius and Seychelles functioned as French plantation colonies, later to be contested by Britain. The balance of power had shifted: Portuguese authority had receded, Omani Arabs and Malagasy monarchs had risen, and European plantation regimes had taken root—setting the stage for the 19th-century surge in slave and ivory exports.

East Africa (1684–1827 CE)

Omani Seas, Highland Courts, and the Caravan Turn

Geography & Environmental Context

East Africa in this age braided the Indian Ocean littoral—Somalia, eastern Ethiopia/Kenya/Tanzania, northern Mozambique, Comoros, Zanzibar–Pemba, Madagascar, Mauritius, Seychelles—with the interior highlands and lake plateaus—Eritrea/Ethiopia, South Sudan, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, inland Kenya/Tanzania, northern Malawi, northwestern Mozambique, Zambia, northern Zimbabwe. Anchors ranged from Swahili port cities(Mogadishu, Mombasa, Kilwa, Sofala, Zanzibar) and island crossroads (Comoros, Mascarenes) to Gondar and the Ethiopian escarpments, the Great Rift lakes (Victoria, Tanganyika, Kivu, Turkana), the inter-lacustrine plateaus, and the savanna woodlands of inland Tanzania and Zambia.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The waning Little Ice Age brought alternating droughts and floods. Pastoral belts in the Horn suffered grazing crises; cyclones periodically battered Comoros, Mauritius, Seychelles; southern Madagascar swung between famine and recovery while the highlands expanded irrigated rice. Rift-lake levels fluctuated, altering fisheries and lakeshore fields; coastal farmers diversified to cushion rainfall volatility.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Littoral & islands: Swahili towns remained Islamic mercantile hubs; diets widened with cassava and maize. Zanzibar–Pemba cultivated rice, coconuts, and, in the early 1800s, rapidly expanding clove plantations under Omani rule; Comoros balanced gardens, rice, and fishing; Mauritius/Seychelles developed sugar and copra plantations with enslaved labor.

-

Madagascar: Merina highland consolidation (late 18th–early 19th c.) intensified rice terracing, tribute, and firearms-backed expansion; Sakalava coastal polities sustained cattle, raiding, and slave exports.

-

Highlands & plateaus: Ethiopian/Eritrean terraces produced teff, barley, wheat; church forests and ox-plough agriculture anchored villages. Great Lakes polities (Buganda, Bunyoro, Rwanda, Burundi) rested on banana gardens, sorghum/millet, beans, and cattle, with dense settlement and court redistribution.

-

Savannas & pastoral belts: Sorghum/millet/maize mosaics spread; fishing and hunting remained key; South Sudan–Turkana–Karamoja transhumance tracked pastures and wells.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Oceanic kit: Dhows with lateen sails stitched ports to Arabia/India; coral-stone mosques, carved doors, and merchant houses framed Swahili towns.

-

Highland engineering: Stone terraces, canals, ox traction, and manuscript ateliers at Gondar; royal compounds and muraled churches.

-

Court regalia & crafts: Drums, ivory trumpets, barkcloth and raffia weaving, lake canoes; island sugar mills, Seychellois coconut presses.

-

Arms & imports: Firearms and powder into coastal and Malagasy polities; in the interior, guns followed caravan lines, supplementing spears and shields.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Omani ascendancy: Oman expelled Portugal from Mombasa (1698) and built a coastwise regime centered on Zanzibar, re-routing Indian Ocean commerce.

-

Caravan turn: Ivory and slave caravans from the Tanzania–Mozambique interior converged on Kilwa, Bagamoyo, Zanzibar, Mozambique Island; inland copper and cattle moved along the Zambezi/central Zambian routes.

-

Madagascar–Mascarenes link: Merina and Sakalava exported captives and cattle to the Mascarenes; textiles, beads, and firearms returned.

-

Horn & Red Sea spurs: Ethiopian caravans carried salt, honey, grain to coastal markets when warfare allowed.

-

Lake corridors: Canoe routes on Victoria and Tanganyika fed court capitals and fisheries.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Coast & islands: Islamic learning (mosques, madrasas, Arabic-script poetry) flourished under Omanipatronage; plantation societies in the Mascarenes blended French Catholicism, African traditions, and creole forms.

-

Highlands: The Gondarine era left castles and muraled churches; Christian feast calendars, monasteries, and pilgrimage routes ordered time.

-

Great Lakes courts: Regnal drums, sacred groves, and oral epics legitimated kingship; clientship(ubuhake/ubugabire) bound households to lords; rainmaking rituals linked rule to fertility.

-

Pastoral rites: Cattle rituals, age-grades, and clan shrines regulated law and memory.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Crop portfolios: Cassava/maize/banana diversification stabilized coastal and savanna diets; highland rice terraces buffered famine.

-

Mobility & storage: Transhumance and widened grazing circuits; dried fish, grain pits, and caravan grain purchases bridged lean years.

-

Rebuilding after storms: Island societies replanted coconuts/rice and repaired harbors; plantation colonies depended on forced labor and imports to absorb shocks.

-

Institutional cushions: Church granaries, court redistribution, waqf and guild charity mitigated crises.

Political & Military Shocks

-

Coastal realignment: Portuguese forts waned as Omani fleets and cannon secured the main ports; Zanzibaremerged as the political–commercial capital.

-

Interior militarization: Merina centralization (c. 1787–1810 →) expanded with firearms; Sakalava raiding persisted. Great Lakes—Buganda pushed lakeward with canoe fleets; Rwanda intensified hill-country tribute; Bunyoro contested supremacy.

-

Slave & ivory booms: Demand from Zanzibar/Mascarenes widened raiding zones in Tanzania, Mozambique, Madagascar; caravan chiefs and coastal patrons gained leverage.

Transition

Between 1684 and 1827, East Africa pivoted from a Portuguese littoral to an Omani oceanic order, while interior kingdoms—from Gondar to Buganda and the Merina highlands—refined statecraft under climatic strain and a growing gun–caravan economy. By the 1820s, Zanzibar orchestrated coastwise trade; Merina hegemony reshaped Madagascar; Great Lakes courts consolidated; and plantation regimes in the Mascarenes took root. The stage was set for the nineteenth-century surge in slave and ivory exports, deeper Indian Ocean entanglement, and, soon after, more direct European intervention.

French efforts to colonize the islands of the western Indian Ocean are more successful than those of the Dutch.

Around 1638 they had taken the islands of Rodrigues and Réunion, and in 1715 an expedition of the French East India Company claims Mauritius for France.

The company establishes a settlement named île de France on the island in 1722.

The company rules until 1764, when, after a series of inept governors and the bankruptcy of the company, Mauritius becomes a crown colony administered by the home government.

One exception among the early company governors is Mahé de la Bourdonnais, who is still celebrated among Mauritians.

During his tenure from 1735 to 1746, he presides over many improvements to the island's infrastructure and promotes its economic development.

He makes Mauritius the seat of government for all French territories in the region, builds up Port Louis, and strengthens the sugar industry by building the island's first sugar refinery.

He also brings the first Indian immigrants, who work as artisans in the port city.

Maritime East Africa (1720–1731 CE): Omani Expansion, Local Resistance, and Economic Consolidation

From 1720 to 1731 CE, Maritime East Africa—covering the Swahili Coast, Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, Seychelles, and Somali coastal cities—experiences deeper integration under Omani influence, sustained internal resistance, and ongoing economic development.

Zanzibar: Economic Dominance and Plantation Expansion

Zanzibar continues to thrive as a commercial powerhouse, driven by a growing clove industry and the expanding trade in slaves. The Omani rulers intensify their agricultural investments, bringing economic prosperity but also deepening societal dependence on forced labor. Zanzibar's strategic and economic prominence strengthens further, solidifying its central role in regional maritime commerce.

Mombasa: Persistent Resistance and Omani Control

Mombasa remains a persistent hotspot of local resistance against Omani dominance, with numerous rebellions attempting to restore local autonomy. The Omanis bolster their military presence, reinforcing key fortifications, notably Fort Jesus, which remains vital in suppressing dissent and securing their strategic position. Despite these tensions, Mombasa maintains a key role in East African trade networks.

Comoros: Internal Strife and Trade Resilience

In the Comoros, political fragmentation continues as local sultanates remain entrenched in ongoing rivalries. Nevertheless, economic resilience persists, with the islands actively involved in the trade of spices, slaves, rice, and ambergris. The Comoros retains significance in regional trading systems, attracting traders despite internal instability.

Madagascar: Strengthening Merina Kingdom and Coastal Commerce

The Merina Kingdom in Madagascar further consolidates its central authority and economic strength, promoting agricultural development and internal stability. Coastal Malagasy communities sustain robust commercial interactions with Arab and European merchants, facilitating a thriving coastal trade environment that ensures economic autonomy despite occasional external interference.

Somali Coastal Cities: Continued Autonomy and Strategic Trade

The Somali coastal cities, including Mogadishu, Merca, and Baraawe, remain economically vigorous and politically autonomous. These cities skillfully manage diplomatic relations with distant powers, such as the Ottoman Turks, safeguarding their economic independence through balanced trade and diplomatic maneuvers.

Seychelles and Mauritius: European Interests and Limited Settlement

Interaction with the Seychelles and Mauritius continues predominantly as sporadic European resource-gathering expeditions rather than permanent colonization efforts. These islands remain relatively peripheral in regional dynamics but persist as useful maritime waypoints for European navigation and exploration.

Cultural Stability and Adaptive Resilience

The Swahili Coast sustains its vibrant Islamic and cultural traditions, carefully integrating external influences without compromising local identity. This adaptive resilience ensures cultural cohesion and stability amid evolving political circumstances.

Legacy of the Era

The period between 1720 and 1731 CE in Maritime East Africa is marked by intensified Omani dominance, resilient local resistance, and steady economic growth. These dynamics collectively shape the region’s trajectory, laying essential foundations for subsequent political and economic transformations.

Maritime East Africa (1732–1743 CE): European Colonial Consolidation and Regional Trade Expansion

From 1732 to 1743 CE, Maritime East Africa—comprising the Swahili Coast, Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, Seychelles, and Somali coastal cities—witnesses increasing European colonial activities alongside continued Omani influence, local resistance, and vibrant regional commerce.

Mauritius (Isle de France): French Colonial Development

France, already controlling neighboring Île Bourbon (Réunion), takes firmer control of Mauritius (renamed Isle de France) under Governor Bertrand-François Mahé de La Bourdonnais in 1735. He significantly develops the colony’s economy, particularly through sugar production. Mahé de La Bourdonnais establishes Port Louis as a strategic naval base and shipbuilding center, constructing significant infrastructure including Government House, Château de Mon Plaisir, and the Line Barracks. Despite its economic growth, the harsh realities of forced labor under the Code Noirpersist, defining enslaved persons explicitly as commodities.

Zanzibar: Intensifying Omani Plantation Economy

Zanzibar further solidifies its economic prominence through the growth of its plantation economy, particularly cloves, under Omani rule. The lucrative trade in enslaved people intensifies, bolstering Zanzibar's strategic position as the economic hub of East African maritime commerce, yet exacerbating human suffering and social divisions.

Mombasa: Continued Resistance and Omani Military Presence

Local resistance remains strong in Mombasa, where repeated uprisings challenge Omani dominance. The Omanis, determined to maintain control, reinforce military fortifications, notably Fort Jesus, sustaining their strategic foothold and facilitating continued regional trade despite internal tensions.

Comoros: Trade and Internal Competition

The Comoros remains politically fragmented into competing sultanates, yet economic resilience endures, driven by trade in spices, slaves, rice, and ambergris. The islands’ involvement in regional commerce attracts continuous interest from Arab, European, and East African traders despite internal instability.

Madagascar: Merina Consolidation and European Encounters

The Merina Kingdom in Madagascar further consolidates its political power and economic foundations, effectively managing internal agriculture and maintaining active trade relations along coastal regions. French colonial settlements, notably at Tolanaro, face severe setbacks, including violent confrontations with local Malagasy groups, leading to eventual abandonment.

Somali Coastal Cities: Trade Autonomy and Diplomatic Balance

Somali coastal cities, particularly Mogadishu, Merca, and Baraawe, continue to thrive economically, maintaining relative autonomy through balanced diplomatic relationships with external powers like the Ottoman Empire. These cities ensure their prosperity by skillfully navigating the complex network of maritime trade and political alliances.

Seychelles: Peripheral European Activity

The Seychelles remains peripheral, with occasional European expeditions focusing on resource exploitation rather than permanent settlement. The islands persist primarily as maritime waypoints for European ships navigating East African waters.

Cultural Continuity and Adaptation

Throughout Maritime East Africa, the Swahili Coast sustains its distinctive cultural and Islamic identity, integrating foreign influences into local traditions and maintaining stability amidst changing colonial and economic dynamics.

Legacy of the Era

Between 1732 and 1743 CE, Maritime East Africa experiences critical developments marked by French colonial establishment in Mauritius, intensified Omani economic control, resilient local resistance, and sustained regional trade networks. These interactions lay foundational patterns influencing subsequent historical developments across the region.

The Code Noir had been established in 1723, to categorize one group of human beings as "goods", in order for the owner of these goods to be able to obtain insurance money and compensation in case of loss of his "goods".

The arrival of French governor Bertrand-François Mahé de La Bourdonnais in 1735 coincides with development of a prosperous economy based on sugar production.

Mahé de La Bourdonnais establishes Port Louis as a naval base and a shipbuilding center.

Under his governorship, numerous buildings had been erected, a number of which are still standing.

These include part of Government House, the Château de Mon Plaisir, and the Line Barracks, the headquarters of the police force.

The island is under the administration of the French East India Company, which will maintain its presence until 1767.