Emperor Kanmu

Emperor of Japan

Years: 737 - 806

Emperor Kanmu (737–806) is the 50th emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession.

Kanmu reigns from 781 to 806.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 10 total

Buddhism begins to spread, despite such machinations, throughout Japan during the ensuing Heian period (794-1185) primarily through two major esoteric sects, Tendai (Heavenly Terrace) and Shingon (True Word).

Tendai originated in China and is based on the Lotus Sutra.

Shingon is an indigenous sect with close affiliations to original Indian, Tibetan, and Chinese Buddhist thought founded by Kukai (also called Kobo Daishi), who greatly impresses the emperors following Emperor Kanmu (782-806) and generations of Japanese, not only with his holiness, but also with his poetry, calligraphy, painting, and sculpture.

Kanmu himself is a notable patron of the otherworldly Tendai sect, which will rise to great power over the ensuing centuries.

A close relationship develops between the Tendai monastery complex on Mount Hiei and the imperial court in its new capital at the foot of the mountain and, as a result, Tendai emphasizes great reverence for the emperor and the nation.

Kammu moves the capital to Heian (Kyoto), which will remain the imperial capital for the next thousand years, doing so not only to strengthen imperial authority but also to improve his seat of government geopolitically.

Kyoto has good river access to the sea and can be reached by land routes from the eastern provinces.

The early Heian period (794-967) continues Nara culture; the Heian capital is patterned on the Chinese capital at Chang' an, as is Nara, but on a larger scale.

Despite the decline of the Taika-Taiho reforms, imperial government is vigorous during the early Heian period.

Indeed, Kammu's avoidance of drastic reform decreases the intensity of political struggles, and he becomes recognized as one of Japan's most forceful emperors.

Earlier imperial sponsorship of Buddhism, beginning with Prince Shōtoku (574–622), had led to a general politicization of the Japanese clergy, along with an increase in intrigue and corruption.

Emperor Kanmu shores up his rule by changing the syllabus of the university.

Confucian ideology still provides the raison d'être for the Imperial government.

In 784, Kanmu authorizes the teaching of a new course based on the Spring and Autumn Annals based on two newly imported commentaries: Kung-yang and Ku-liang.

These commentaries use political rhetoric to promote a state in which the Emperor, as "Son of Heaven," should extend his sphere of influence to barbarous lands, thereby gladdening the people.

In 784, Emperor Kanmu shifts his capital from Nara to …

…Nagaoka-kyō in a move that was said to be designed to edge the powerful Nara Buddhist establishments out of state politics—while the capital moves, the major Buddhist temples, and their officials, stay put.

Indeed there had been a steady stream of edicts issued from 771 right through the period of Kūkai's studies which, for instance, sought to limit the number of Buddhist priests, and the building of temples.

However the move is to prove disastrous and will be followed by a series of natural disasters including the flooding of half the city.

Kanmu's armies are meanwhile pushing back the boundaries of his empire.

This leads to an uprising, and in 789 a substantial defeat for Kanmu's troops.

Also in 789 there is a severe drought and famine—the streets of the capital are clogged with the sick, and with people avoiding conscription into the military or as forced labor.

Many disguise themselves as Buddhist priests for the same reason.

Japanese emperor Kammu, irritated at Buddhist priestly intrusion into state affairs, decides, in 794, to move the capital from Nara to …

…Heian-kyo (in the center of the present-day city of Kyoto).

Reasons cited for this move include frequent flooding of the rivers that had promised better transportation; disease caused by the flooding, affecting the empress and crown prince; and fear of the spirit of the late Prince Sawara.

Kanmu had abandoned universal conscription in 792, but he still wages major military offensives to subjugate the Ainu, a north Asian Caucasoid people, sometimes referred to as Emishi, living in northern and eastern Japan.

After making temporary gains in 794, in 797 Kanmu appoints a new commander under the title seii taishogun (barbarian-subduing generalissimo, often referred to as shogun).

By 801 the shogun has defeated the Ainu and extended the imperial domains to the eastern end of Honshu.

Imperial control over the provinces is tenuous at best, however, and in the ninth and tenth centuries much authority will be lost to the great families who disregard the Chinese-style land and tax systems imposed by the government in Kyoto.

Stability comes to Heian Japan, but, even though succession is ensured for the imperial family through heredity, power again concentrates in the hands of one noble family, the Fujiwara.

Wake no Hiroyo, one of Saicho's earliest supporters in the Court, had invited Saicho to give lectures at Takaosanji along with fourteen other eminent monks.

Saicho was not the first to be invited, indicating that he was still relatively unknown in the Court, but still rising in prominence.

The success of the Takaosanji lectures, plus Saicho's association with Wake no Hiroyo, had soon caught the attention of Emperor Kanmu, who had consulted with Saicho about propagating his Buddhist teachings further, and to help bridge the traditional rivalry between the Hosso (Yogacara) and Sanron (Madhyamika) schools.

The emperor had granted a petition by Saicho to journey to China to further study Tiantai doctrine in China, and bring back more texts.

Saicho was expected to only remain in China for a short time, however.

Saicho can read Chinese language, but is unable to speak it at all, thus he is allowed to bring a trusted disciple along named Gishin, who apparently can communicate in Chinese.

Gishin will later become one of the head monks of the Tendai order after Saicho.

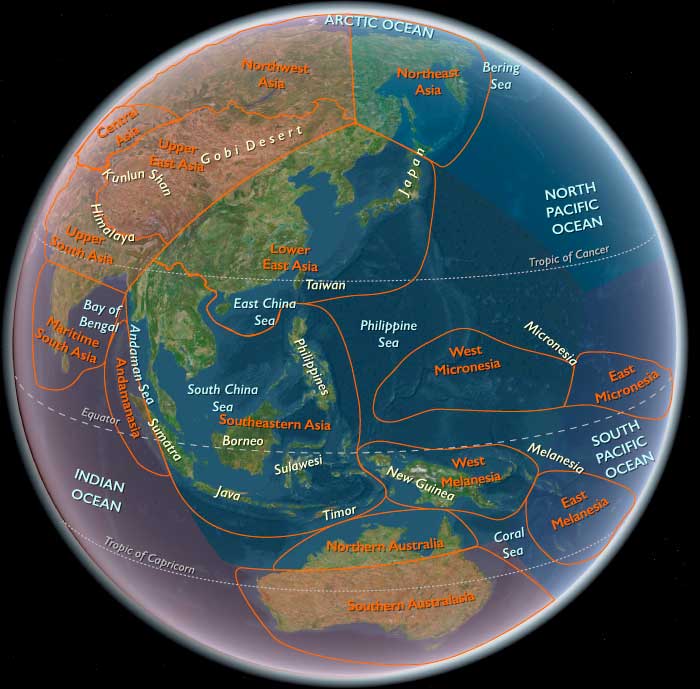

Saicho had been part of the four-ship diplomatic mission to Tang Dynasty China in 803.

The ships were forced to turn back due to heavy winds, where they had spent some time at Dazaifu.

During this time, Saicho had likely met Kukai, who had been sent to China on a similar mission though he was expected to stay much longer.

When the ships set sail again, two sank during a heavy storm, but Saicho's ship had arrived at the port of Ningbo, then known as Mingzhou, in northern Zhejiang Province in 804.

Shortly after arrival, permission had been granted for Saicho and his party to travel to Mount Tiantai and he had been introduced to the Seventh Patriarch of Tiantai Buddhism, named Tao-sui, who becomes his primary teacher during his time in China.

Tao-sui is instrumental in teaching Saicho about Tiantai methods of meditation, Tiantai monastic discipline and orthodox teachings.

Saicho had remained under this instruction for approximately 135 days.

Saicho spends the next several months copying various Buddhist works with the intention of bringing them back to Japan later.

While some works exist n Japan already, Saicho feels that they suffer from copyist errors or other defects, and makes fresh copies.

Once the task is completed, Saicho and his party return to Ningbo, but the ship is harbored in Fuzhou at the time, and will not return for six weeks.

During this time, Saicho goes to Yuezhou (modern-day Shaoxing) and seeks out texts and information on esoteric Buddhism.

The Tiantai school had originally only utilized "mixed" (zōmitsu) ceremonial practices, but over time, esoteric Buddhism has taken on a greater role.

By the time of Saicho, a number of Tiantai Buddhist centers offered esoteric training, and both Saicho and Gishin received initiation at a temple in Yuezhou.

However, it's unclear what transmission or transmissions(s) they received.

Some evidence suggests that Saicho did not receive the dual transmissions of the Diamond Realm and the Womb Realm.Instead, it is thought he may have only received the Diamond Realm transmission, but the evidence is not conclusive one way or the other.

Finally, on the tenth day of the fifth month of 805, Saicho and his party return to Ningbo and after compiling further bibliographies, board he ship back for Japan; they will arrive in Tsushima on the fifth day of the sixth month.

Although Saicho has only stayed in China for a total of 8 months, his return is eagerly awaited by the Court in Kyoto.

Kukai arrives back in Japan in 806 as the eighth Patriarch of Esoteric Buddhism, having learnt Sanskrit and its Siddham script, studied Indian Buddhism, as well as having studied the arts of Chinese calligraphy and poetry, all with recognized masters.

He also arrives with a large number of texts, many of which are new to Japan and are esoteric in character, as well as several texts on the Sanskrit language and the Siddham script.

In Kukai's absence, however, Emperor Kammu had died and has been replaced by Emperor Heizei, who exhibits no great enthusiasm for Buddhism.

Kukai's return from China is eclipsed by Saicho, the founder of the Tendai school, who finds favor with the court during this time.

Saicho has already had esoteric rites officially recognized by the court as an integral part of Tendai, and has already performed the abhisheka, or initiatory ritual, for the court by the time Kūkai returns to Japan.

With Emperor Kammu's death, Saicho's fortunes had begun to wane.