Gengshi of Han

emperor of the Han dynasty and Prince of Huaiyang

Years: 25BCE - 25

Emperor Gengshi of Han (d. strangled CE 25), also known as the Prince of Huaiyang (the title that Emperor Guangwu (Liu Xiu) gave him in absentia after he was deposed by Chimei forces), courtesy name Shenggong, is an emperor of the restored Chinese Han Dynasty following the fall of Wang Mang's Xin Dynasty.

He is not to be confused with Emperor Guangwu, who founded the succeeding Eastern Han Dynasty.

He is viewed as a weak and incompetent ruler, who briefly rules over an empire willing to let him rule over them, but is unable to keep this empire together.

He is eventually deposed by the Chimei and strangled a few months after his defeat.

Traditional historians treat his emperor status ambiguously—and sometimes he is referred to as an emperor (with reference to his era name—thus, Emperor Gengshi) and sometimes is referred to by his Eastern Han-granted title (Prince of Huaiyang) because Eastern Han is later viewed as the "legitimate" restoration of the Han Dynasty, implying that he was only a pretender.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 18 total

Maritime East Asia (45 BCE–99 CE): Dynastic Turmoil, Regional Influence, and Rebellions

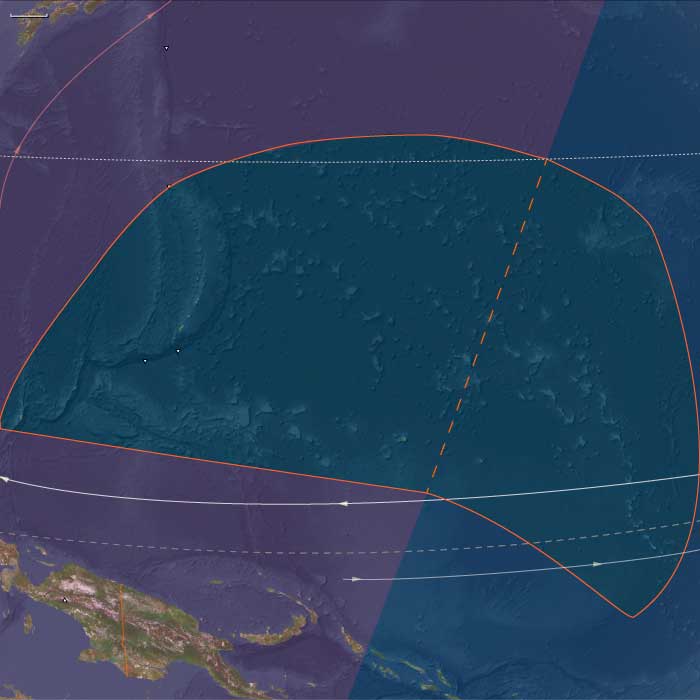

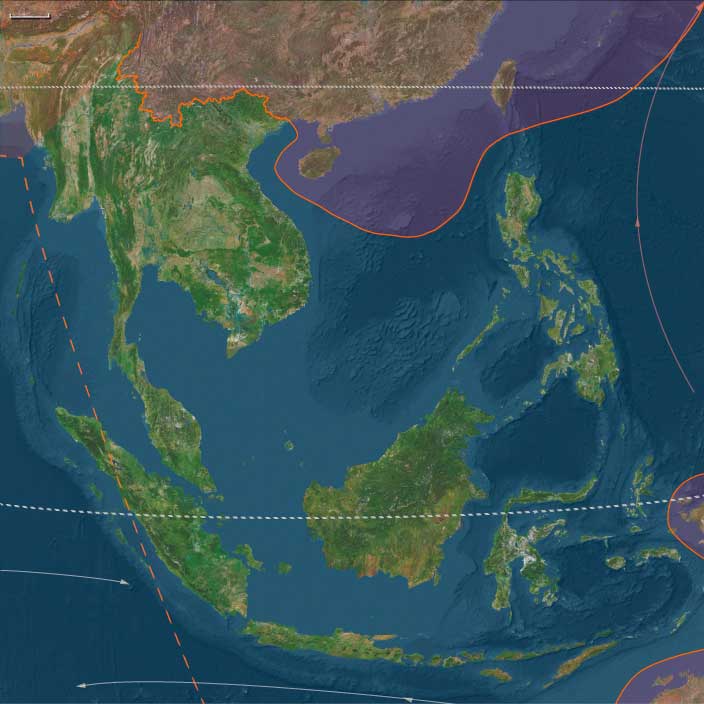

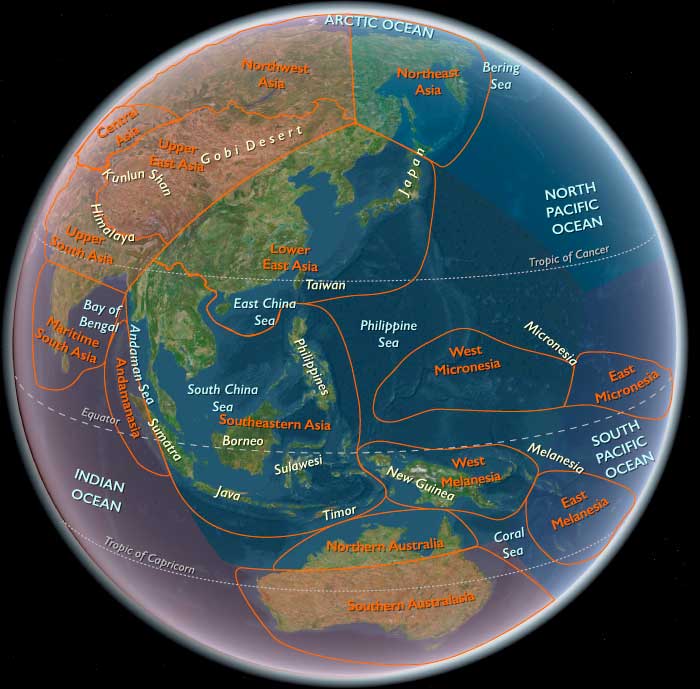

Between 45 BCE and 99 CE, Maritime East Asia—comprising lower Primorsky Krai, the Korean Peninsula, the Japanese Archipelago below northern Hokkaido, Taiwan, and southern, central, and northeastern China—experiences significant political upheavals, regional expansions, and continued cultural and technological advancements during the later Han dynasty.

Political Instability and Dynastic Change

The early first century CE is marked by dynastic turbulence, most notably during Wang Mang's Xin Dynasty. Major agrarian rebellions originating in modern Shandong and northern Jiangsu drain the Xin dynasty’s resources, eventually leading to Wang Mang’s overthrow. The Lülin rebellion elevates Liu Xuan (Emperor Gengshi) to briefly restore the Han dynasty. However, internal divisions soon see Gengshi replaced by the Chimei faction's puppet emperor, Liu Penzi, who himself falls due to administrative incompetence.

By 30 CE, the Eastern Han dynasty under Emperor Guangwu (Liu Xiu) reestablishes control, overcoming these rebellions and restoring a degree of central authority.

Expansion and Influence in Korea

Lelang (Nangnang), near present-day P'yongyang, becomes a significant center of Chinese governance, culture, industry, and commerce, maintaining its prominence for approximately four centuries. Its extensive influence draws Chinese immigrants and imposes tributary relationships on several Korean states south of the Han River, shaping regional civilization and governance.

The Korean Peninsula witnesses substantial agrarian development, notably through advanced rice agriculture and extensive irrigation systems. By the first three centuries CE, walled-town states cluster into three federations: Jinhan, Mahan, and Byeonhan, marking significant strides toward regional organization and agricultural efficiency.

Goguryeo and Han Relations

During the instability of Wang Mang’s rule, the Korean kingdom of Goguryeo exploits the turmoil, frequently raiding Han's Korean prefectures. It is not until 30 CE that Han authority is firmly restored, reasserting control over these border territories.

Xiongnu and Frontier Conflicts

Wang Mang's hostile policy toward the northern nomadic Xiongnu tribes culminates in significant frontier conflicts. By 50 CE, internal division splits the Xiongnu into the Han-allied Southern Xiongnu and the antagonistic Northern Xiongnu. The Northern Xiongnu seize control of the strategically important Tarim Basin in 63 CE, threatening Han’s crucial Hexi Corridor.

However, following their defeat in 91 CE, the Northern Xiongnu retreat into the Ili River valley, allowing the Xianbei nomads to occupy extensive territories from Manchuria to the Ili River, reshaping regional power dynamics.

Technological and Cultural Developments

This period sees continued advancements in mathematics and commerce. Notably, the influential Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art (Jiu Zhang Suan Shu) documents the first known use of negative numbers, employing distinct color-coded counting rods to represent positive and negative values, and presenting sophisticated methods for solving simultaneous equations.

Peak and Decline under Emperor Zhang

The reign of Emperor Zhang (75–88 CE) is retrospectively regarded as the Eastern Han dynasty's zenith, characterized by administrative stability and cultural flourishing. However, subsequent emperors witness increasing eunuch interference in court politics, sparking violent power struggles between eunuchs and imperial consort clans, foreshadowing dynastic decline.

Legacy of the Age: Turbulence, Expansion, and Innovation

Thus, the age from 45 BCE to 99 CE is defined by significant political turbulence, territorial expansion, technological innovation, and sustained cultural influence. Despite internal strife, this era reinforces critical foundations for subsequent East Asian civilizations, shaping regional dynamics profoundly.

Major agrarian rebellion movements against Wang Mang's Xin Dynasty, initially active in the modern Shandong and northern Jiangsu region, eventually lead to Wang Mang's downfall by draining his resources; this allows the leader of the other movement (the Lülin), Liu Xuan (Emperor Gengshi) to overthrow Wang and temporarily establish an incarnation of the Han Dynasty under him.

Chimei forces eventually overthrow Emperor Gengshi and place their own Han descendant puppet, Emperor Liu Penzi, on the throne, but briefly: the Chimei leaders' incompetence in ruling the territories under their control, which matches their brilliance on the battlefield, causes the people to rebel against them, forcing them to try to withdraw homeward.

They surrender to Liu Xiu's (Emperor Guangwu’s) newly established Eastern Han regime when he blocks their path.

The state of Goguryeo had been free to raid Han's Korean prefectures during the widespread rebellion against Wang Mang; the Han dynasty does not reaffirm its control over the region until CE 30.

The rebellion led by the Trung Sisters of Vietnam is crushed after a few years.

Wang Mang had renewed hostilities against the Xiongnu, who are estranged from Han until their leader, a rival claimant to the throne against his cousin, submits to Han as a tributary vassal in 50.

This creates two rival Xiongnu states: the Southern Xiongnu led by a Han ally, and the Northern Xiongnu led by a Han enemy.

During the turbulent reign of Wang Mang, Han had lost control over the Tarim Basin, which is conquered by the Northern Xiongnu in 63 and used as a base to invade Han's Hexi Corridor in Gansu.

After the Northern Xiongnu defeat and flight into the Ili River valley in 91, the nomadic Xianbei occupy the area from the borders of the Buyeo Kingdom in Manchuria to the Ili River of the Wusun people.

The reign of Emperor Zhang, from 75–88, will come to be viewed by later Eastern Han scholars as the high point of the dynastic house.

Subsequent reigns will be increasingly marked by eunuch intervention in court politics and their involvement in the violent power struggles of the imperial consort clans.

The Chimei or Red Eyebrows is, along with Lülin, one of the two major agrarian rebellion movements against Wang Mang's short-lived Xin Dynasty.

The Chimei rebellion, initially active in the modern Shandong and northern Jiangsu regions, eventually leads to Wang Mang's downfall by draining his resources, allowing Liu Xuan (Emperor Gengshi), leader of the Lülin, to overthrow Wang and temporarily reestablish an incarnation of the Han Dynasty.

Eventually, Chimei forces overthrow Emperor Gengshi and place their own Han descendant puppet, teenage Emperor Liu Penzi, on the throne, who rules briefly until the Chimei leaders' incompetence in ruling the territories under their control (which matches their brilliance on the battlefield) causes the people to rebel against them, forcing them to retreat and attempt to return home.

When their path is blocked by the army of the newly established Eastern Han regime of Liu Xiu (Emperor Guangwu), they surrender to him.

The joint forces under Liu Yan's leadership have a major victory in 23 over Zhen Fu, the governor of the prefecture of Nanyang, killing him.

The coalition now besieges the important city of Wancheng (the capital of Nanyang prefecture, in modern Nanyang, Henan).

Many other rebel leaders have become jealous of Liu Yan's capabilities by this point, and while a good many of their men admire Liu Yan and want him to become the emperor of a newly declared Han Dynasty, the disgruntled leaders have other ideas.

They find another local rebel leader, Liu Xuan, a third cousin of Liu Yan, who is claiming the title of General Gengshi at the time and who is considered a weak personality, and request that he be made emperor.

Liu Yan initially opposes this move and instead suggests that Liu Xuan carry the title "Prince of Han" first (echoing the founder of the Han Dynasty, Emperor Gao).

The other rebel leaders refuse, and in early 23, Liu Xuan is proclaimed emperor.

Liu Yan becomes prime minister.

Emperor Gengshi is fearful of Liu Yan's capabilities and keenly aware that many of Liu Yan's followers are angry that he had not been made emperor.

One, Liu Ji, is particularly critical of Emperor Gengshi.

Emperor Gengshi arrests Liu Ji and wants to execute him, but Liu Yan tries to intercede.

Emperor Gengshi takes this opportunity to execute Liu Yan as well.

However, ashamed of what he has done, he spares Liu Yan's brother Liu Xiu, and in fact creates Liu Xiu the Marquess of Wuxin.

Emperor Gengshi now commissions two armies, one led by Wang Kuang, targeting Luoyang, and the other led by Shentu Jian and Li Song, targeting Chang'an directly.

All the people along the way gather, welcome, and join the Han forces.

Shentu and Li quickly reach the outskirts of Chang'an.

In response, the young men within Chang'an also rise up and storm Weiyang Palace, the main imperial residence.

Wang died in the battle at the palace, as does his daughter Princess Huanghuang (the former empress of Han).

After Wang dies, the crowd fight over the right to have the credit for having killed Wang, and tens of soldiers die in the ensuing fight.

Wang's body is cut into pieces, and his head is delivered to the provisional Han capital Wancheng, to be hung on the city wall.

Emperor Gengshi temporarily moves his capital from Wacheng to Luoyang after Wang Mang's death.

He then issues edicts to the entire empire, promising to allow Xin local officials who submit to him to keep their posts, and sends diplomats to try to persuade Chimei generals to submit as well.

For a brief period, nearly the entire empire shows at least nominal submission to Emperor Gengshi as the legitimately restored Han emperor—even including the powerful Chimei general Fan Chong, who, indeed, goes to stay in Luoyang under promises of titles and honors.

However, this policy is applied inconsistently, and local governors soon become apprehensive about giving up their power.

Some twenty-odd Chimei generals have gone to Luoyang and been created marquesses but have not been given any actual marches, and, seeing that their men are about to disband, they flee Luoyang for their base at Puyang.

Fan, in particular, leaves the capital and returns to his troops.

In response, Emperor Gengshi sends various generals out to try to calm the local governors and populace; these include Liu Xiu, who is sent to pacify the region north of the Yellow River.

The strategist Liu Lin suggests to Liu Xiu to break the Yellow River levee and destroy the Chimei by this manner, but Liu Xiu refuses.

The people begin to see that the powerful officials around Emperor Gengshi are in fact uneducated men lacking ability to govern; this further makes them lose confidence in his governance.

Emperor Gengshi's governance is in fact immediately challenged by a major pretender in winter 23.

A fortuneteller in Handan named Wang Lang claims to be actually named Liu Ziyu and a son of Emperor Cheng.

He claims that his mother was a singer in Emperor Cheng's service, and that Empress Zhao Feiyan had tried to kill him after his birth, but that a substitute child was killed indeed.

After he spreads these rumors, the people of Handan begin to believe that he is a genuine son of Emperor Cheng, and the prefectures north of the Yellow River quickly pledge allegiance to him as emperor.

Liu Xiu is forced to withdraw to the northern city of Jicheng (in modern Beijing).

After some difficulties, Liu Xiu is able to unify the northern prefectures still loyal to Emperor Gengshi and besiege Handan in 24, killing Wang Lang.

Emperor Gengshi puts Liu Xiu in charge of the region north of the Yellow River and creates him the Prince of Xiao, but Liu Xiu, still aware that he is not truly trusted and secretly angry about his brother's death, secretly plans to depart from Emperor Gengshi's rule.

He begins to strip other Emperor Gengshi-commissioned generals of their powers and troops, and concentrates the troops under his own command.