James Wilkinson

American soldier and diplomat

Years: 1757 - 1825

James Wilkinson (March 24, 1757 – December 28, 1825) is an American soldier and diplomat who is associated with several scandals and controversies.

He serves in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, but is twice compelled to resign.

He is twice the Commanding General of the United States Army, appointed first Governor of the Louisiana Territory in 1805, and commands two unsuccessful campaigns in the St. Lawrence theater during the War of 1812.

After his death, he is discovered to have been a paid agent of the Spanish Crown

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 21 total

News accounts are published in Pennsylvania on August 11 and on August 22 as far away as Virginia.

Often the accounts become more exaggerated as they travel, describing indiscriminate killings of large numbers of Loyalists and Patriots alike.

Burgoyne's campaign had intended to use the natives as a means to intimidate the colonists; however, the American reaction to the news is not the one hoped for.

The propaganda war receives a boost after Burgoyne writes a letter to the American general Horatio Gates, complaining about American treatment of prisoners taken in the August 17 Battle of Bennington.

Gates' response is widely reprinted:

That the savages of America should in their warfare mangle and scalp the unhappy prisoners who fall into their hands is neither new nor extraordinary; but that the famous Lieutenant General Burgoyne, in whom the fine gentleman is united with the soldier and the scholar, should hire the savages of America to scalp europeans and the descendants of europeans, nay more, that he should pay a price for each scalp so barbarously taken, is more than will be believed in England. [...] Miss McCrae, a young lady lovely to the sight, of virtuous character and amiable disposition, engaged to be married to an officer of your army, was [...] carried into the woods, and there scalped and mangled in the most shocking manner [...]

—Gates to Burgoyne

News accounts elaborate on her beauty, describing her as "lovely in disposition, so graceful in manners and so intelligent in features, that she was a favorite of all who knew her", and that her hair "was of extraordinary length and beauty, measuring a yard and a quarter".

One of the only contemporary accounts by someone who actually saw her was that of James Wilkinson, who describes her as "a country girl of honest family in circumstances of mediocrity, without either beauty or accomplishments."

Later accounts will embellish details; historian Richard Ketchum notes that the color of her hair has been described as everything from black to blonde to red; he also cites an 1840s examination of an alleged lock of her hair that described it as "reddish".

Her death, and those of others in similar raids, inspire some of the resistance to Burgoyne's invasion leading to his defeat at the Battle of Saratoga.

The effect will expand as reports of the incident are used as propaganda to excite rebel sympathies later in the war, especially before the 1779 Sullivan Expedition.

David Jones, apparently bitter over the experience, will never marry and will settle in Canada as a United Empire Loyalist.

The story will eventually become a part of American folklore.

An anonymous poet will write "The Ballad of Jane McCrea", which will be set to music and become a popular folk song.

In Philadelphia in 1799, Ricketts' Circus will perform "The Death of Miss McCrea", a pantomime co-written by John Durang, and John Vanderlyn will paint a portrait (shown upper right) in 1803.

Several markers will be placed in and near Fort Edward commemorating her death.

Several factors had contributed to the desire of the residents of Kentucky County to separate from Virginia.

First, travel to the state capital is long and dangerous.

Second, offensive use of local militia against raids by natives requires authorization from the governor of Virginia.

Last, Virginia has refused to recognize the importance of trade along the Mississippi River to Kentucky's economy.

Trade with the Spanish colony of New Orleans, which controls the mouth of the Mississippi, is forbidden.

The magnitude of these problems had increased with the population of Kentucky County, leading Colonel Benjamin Logan to call a constitutional convention in Danville in 1784.

Over the next six years, nine more conventions had been held.

During one, General James Wilkinson had proposed secession from both Virginia and the United States to become a ward of Spain, but the idea was defeated.

Finally, on June 1, 1792, the United States Congress accepts the Kentucky Constitution and admits it as the 15th state.

The federal Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 had met vigorous opposition in Kentucky, led in part by the young politician Henry Clay (who two decades later will become known on the state and national scenes as the “great compromiser”).

Events leading to a second state constitution in 1800 reveal an internal division (that will continue to characterize the state).

Farmers, who float their grain, hides, and other products on flatboats down the Mississippi to Spanish-held New Orleans, ally themselves with other antislavery forces to oppose slaveholders and businessmen.

Lieutenant Colonel James Wilkinson, a central figure in Kentucky politics, had in 1787 taken a secret oath of allegiance to Spain and had begun intrigues to bring the western settlements of Kentucky under the influence of the Louisiana authorities.

Officially known as “Number Thirteen”, Wilkinson receives a Spanish pension until October 1800, when Napoleon induces Spain to restore Louisiana to France.

With this agreement, confirmed in March 1801 as the Treaty of San Ildefonso, go not only the growing and commercially significant port of New Orleans but also the strategic mouth of the Mississippi River.

This treaty of supposed retrocession creates much uneasiness in the United States.

Claiborne is appointed as the area's first American governor.

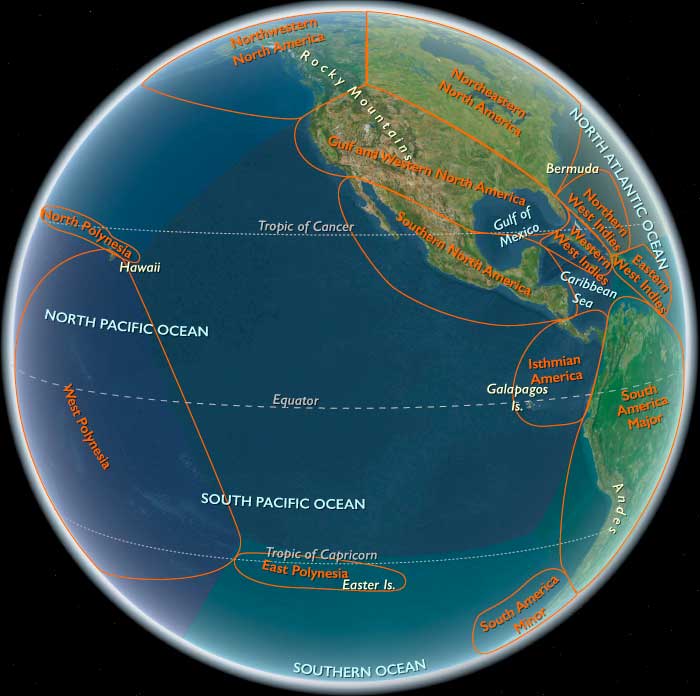

Northeastern North America

(1804 to 1815 CE): Exploration, Conflict, and Emerging National Identity

The years 1804 to 1815 in Northeastern North America marked an era of pivotal exploration, territorial expansion, intense conflicts, and significant developments shaping American national identity. During this period, Americans eagerly pursued westward expansion, leading to prolonged conflicts known as the American Indian Wars, while the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 nearly doubled the nation's size. Intensified slavery, frontier settlement, and evolving political landscapes also characterized this era, culminating in the War of 1812, a conflict that strengthened American nationalism despite its ambiguous conclusion.

Landmark Western Exploration

Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806)

Following the Louisiana Purchase (1803), championed by the third U.S. president, Thomas Jefferson, the historic expedition led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, known as the Corps of Discovery, explored territories west of the Mississippi River. Their journey to the Pacific Ocean and back significantly expanded geographic and scientific understanding of the continent.

Zebulon Pike’s Explorations (1805–1807)

Explorer Zebulon Pike simultaneously conducted extensive explorations, mapping the Upper Mississippi River region and the southern parts of the newly acquired Louisiana Territory, enhancing U.S. knowledge of its expanding frontier.

Frontier Settlement and Westward Expansion

The Louisiana Purchase encouraged a vast wave of American settlers to push westward beyond the Appalachians. The frontier reached the Mississippi River by 1800, and new states such as Ohio (1803) were rapidly admitted into the Union. Settlements expanded into the Ohio Country, the Indiana Territory, and the lands of the lower Mississippi valley, particularly around St. Louis, which, after 1803, became a major gateway to the West. Americans enthusiastically pursued opportunities in new territories, sparking tensions and conflict with indigenous peoples.

In South Carolina, the antebellum economy flourished, particularly through cotton cultivation after Eli Whitney's invention of the cotton gin in 1793. Though nominally democratic, South Carolina remained tightly controlled by a powerful planter elite, with strict property and slaveholding requirements limiting political participation to wealthy landowners.

War of 1812 and Its Impacts

Causes and Conflicts

The U.S. declared war against Great Britain in 1812, motivated by grievances such as impressment of American sailors, trade restrictions, and Britain's support for Native American resistance. Prominent Federalist leaders, including Boston-based politician Harrison Gray Otis, strongly opposed the war, advocating states' rights at the Hartford Convention (1814).

Combat and Indigenous Alliances

Intense battles occurred along the Canadian-American frontier. Native leaders like Tecumseh allied with Britain, resisting American westward expansion until Tecumseh's defeat and death at the Battle of the Thames (1813). The war saw notable events such as the British burning of Washington D.C. (1814) and the failed British assault on Baltimore, immortalized by Francis Scott Key's poem "The Star-Spangled Banner."

Conclusion and National Identity

Ending in stalemate with the Treaty of Ghent (1814), the war nonetheless bolstered U.S. nationalism and confirmed the nation's resilience. The final American victory at the Battle of New Orleans (January 1815) elevated Andrew Jackson as a national hero.

Social, Economic, and Cultural Developments

Expansion of Slavery and Southern Economy

Despite the ideals of liberty proclaimed in the American Revolution, slavery expanded dramatically in the Deep South. Following the failed Gabriel’s Rebellion (1800) in Virginia, Southern planters imposed even harsher controls on enslaved people. By 1810, South Carolina had a large enslaved population—nearly half of its residents—essential for its thriving cotton economy. Powerful merchant families, such as the Boston-based Cabots and Perkins, continued amassing wealth through shipping and involvement in slave-related trade, exemplifying the complex intersections of commerce, slavery, and politics.

Religious Revival and Frontier Culture

The Second Great Awakening profoundly influenced frontier society, encouraging evangelical Protestant revivals, camp meetings, and increased participation in denominations like Baptists and Methodists. Large camp meetings, including the famous gathering at Cane Ridge, Kentucky (1801), energized religious life and social reform movements.

Jeffersonian Democracy and Early Political Developments

Thomas Jefferson, a leading advocate for individual liberty and separation of church and state, profoundly shaped U.S. politics in the early 1800s. Serving as president from 1801 to 1809, he oversaw the Louisiana Purchase, which significantly expanded the nation's territory. Despite advocating democratic ideals, Jefferson himself exemplified contradictions: he was an eloquent champion of freedom who remained economically reliant on enslaved labor at his plantation home, Monticello, and was likely father to several children with Sally Hemings, an enslaved African-American woman.

Jefferson and his successor, James Madison (1809–1817)—both clean-shaven like their predecessors, Washington and Adams—oversaw the complex diplomatic tensions and conflicts culminating in the War of 1812.

Domestic Turmoil and Conspiracy

During this era, internal U.S. affairs were unsettled. The Spanish withdrawal of the American “right of deposit” at New Orleans (1802) escalated tensions, fueling discussions of war. The controversial third vice-president, Aaron Burr, became embroiled in scandal, allegedly conspiring in 1805–1807 to foment secession in the western territories alongside General James Wilkinson. Although his conspiracy remains debated among historians, it highlighted the fragility of national unity during this period.

International Commerce and Opium Trade

Prominent American merchant families such as the Cabots of Boston continued to build fortunes through shipping, privateering, and participation in the Triangular Trade involving enslaved Africans. Samuel Cabot Jr., through marriage to Eliza Perkins, daughter of merchant king Colonel Thomas Perkins, expanded family wealth by engaging in controversial opium trade with China via British smugglers, highlighting the far-reaching commercial interests of prominent American families during this period.

Additionally, major institutions like Brown University began confronting the economic legacy of slavery, addressing their involvement in slave trading as well as their complex roles in the nation’s commercial and academic development.

Native American Realignment and the American Indian Wars

American eagerness for westward expansion led to escalating violence and displacement of indigenous peoples. During the War of 1812, some Native tribes allied with the British as a strategy against American expansion. However, the defeat of Native coalitions severely weakened resistance, enabling accelerated settler encroachment on indigenous territories. Tribes like the Mandan, Assiniboine, and Crow faced ongoing conflicts, devastating epidemics, and the pressures of expanding American settlements.

Legacy of the Era (1804–1815 CE)

From 1804 to 1815, Northeastern North America witnessed transformative developments shaping national identities, geopolitical alignments, and social structures. The era was defined by dramatic territorial growth through the Louisiana Purchase, intense frontier conflict, expanded slavery, profound religious awakenings, and political controversies. While the War of 1812 tested American resilience, it ultimately strengthened the nation's identity. Simultaneously, the persistence and expansion of slavery deepened social divisions that would have profound consequences for decades to follow.

Southern planters in the wake of Gabriel's Rebellion impose even harsher controls on the region's enslaved Africans and African-Americans.

During this era, the Tripolitanian War (1800-1805), the War of 1812, and the Creek War (1813-1814) have the side effect of muting rebellious tendencies among the United States citizenry.

The withdrawal in 1802 by the Spanish district administrator of the United States' “right of deposit” at New Orleans—the privilege of storing goods there for later reshipment —greatly increases U.S. uneasiness concerning Spain and leads to much talk of war.

In what becomes known as the Aaron Burr conspiracy, the controversial third vice-president (1801-1805) possibly (historians remain divided) plots with his friend Jamie Wilkinson to foment a secessionist movement in the West.

Arrest warrants are issued for Burr, whom many now view as a murderer.

He flees to South Carolina, where his daughter lives with her family, but soon returns to Philadelphia, where he contacts his friend James Wilkinson, former United States Army Lieutenant Colonel and double agent for Spain who, after the United States' purchase of Louisiana, has become governor of that portion of the territory above the 33rd parallel.

In his double capacity as governor of the territory and commanding officer of the army, Wilkinson harbors ambitions to conquer the Mexican provinces of Spain and perhaps set up an independent government.

James Wilkinson and Aaron Burr, expecting war to break out between the United States and Spain over boundary disputes, plan an invasion of Mexico in order to establish an independent government there.

Possibly—the record is unclear—they also discuss a plan to foment a secessionist movement in the West and, joining it to Mexico, to found an empire on the Napoleonic model.

General James Wilkinson is one of Aaron Burr’s most important co-conspirators in what will become known as the Burr conspiracy.

Though it will eventually be discovered that his involvement in the conspiracy was most likely an attempt to further his own personal and political goals, he works closely with Burr to develop a plan for secession.

The commanding General of the Army at the time, Wilkinson is known for his corrupt practices, including his attempt to separate Kentucky and Tennessee from the union during the 1780s.

Burr persuades President Thomas Jefferson to appoint Wilkinson to the position of Governor of the Territory of Louisiana in 1805.

Wilkinson will later come to betray Burr by revealing his plot to Jefferson and denying all involvement in the conspiracy.

While Burr was still Vice President, in 1804 he had met with Anthony Merry, the British Minister to the United States.

As Burr told several of his colleagues, he had suggested to Merry that the British might regain power in the Southwest if they contributed guns and money to his expedition.

Burr had offered to detach Louisiana from the Union in exchange for a half a million dollars and a British fleet in the Gulf of Mexico.

Merry wrote, "It is clear Mr. Burr... means to endeavour to be the instrument for effecting such a connection - he has told me that the inhabitants of Louisiana ... prefer having the protection and assistance of Great Britain."

"Execution of their design is only delayed by the difficulty of obtaining previously an assurance of protection & assistance from some foreign power."

(Melton, Buckner, Aaron Burr, Conspiracy to Treason, 2002) In 1805, Burr conceives plans to emigrate, which he claims is for the purpose of taking possession of land in the Texas Territories leased to him by the Spanish (the lease is granted, and copies still exist).

This year, Burr travels throughout Louisiana.

In the spring, Burr meets with Harman Blennerhassett, who proves valuable in helping Burr further his plan.

He provides friendship, support, and most importantly, access to the island which he owns on the Ohio River, about 2 miles (3 km) below what is now Parkersburg, West Virginia.

In 1805, Blennerhassett offers to provide Burr with substantial financial support.

Burr and his co-conspirators use this island as a storage space for men and supplies.

Burr tries to recruit volunteers to enter Spanish territories.

In New Orleans, he meets with the Mexican Associates, a group of criollos whose objective is to conquer Mexico.

Burr is able to gain the support of New Orleans’ Catholic bishop for his expedition into Mexico.

Reports of Burr's plans first appear in newspaper reports in August 1805, which suggest that Burr intends to raise a western army and "to form a separate government."

In this year, Joseph Hamilton Daviess, the federal District Attorney for Kentucky, brings charges against Burr, claiming that he intends to make war with Mexico.

With the help of his young attorney, Henry Clay, Burr is able to have the case dismissed.

In November 1805, Burr again meets with Merry and asks for two or three ships of the line and money.

Merry informs Burr that London has not yet responded to Burr's plans which he had forwarded the previous year.

Merry gives him fifteen hundred dollars.

Those Merry work for in London express no interest in furthering an American secession.

Aaron Burr had contacted the Spanish minister, Carlos Martínez de Irujo y Tacón, in early 1806 and told him that his plan is not just western succession, but the capture of Washington.

Irujo had written to his masters in Madrid about the coming "dismemberment of the colossal power which was growing at the very gates" of New Spain. (Melton, Buckner, Aaron Burr, Conspiracy to Treason, 2002)

Irujo had given Burr a few thousand dollars to get things started.

The Spanish government in Madrid takes no action.

Jo Daviess, United States District Attorney for Kentucky, writes Jefferson several letters in February and March 1806, warning him of possible conspiratorial activities by Burr.

Jefferson dismisses Daveiss’ accusations against Burr, a Democratic-Republican, as politically motivated.

In the spring of 1806, Burr has his final meeting with Anthony Merry, Britain's representative to the United States in Washington, D.C. from 1803.

In this meeting Merry informs Burr that still no response has been received from London.

Burr tells Merry, "with or without such support it certainly would be made very shortly." (Melton, Buckner, Aaron Burr, Conspiracy to Treason, 2002).