Australasia

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 20 total

Australasia (1252–1395 CE): Southern Voyages, Temperate Adaptations, and Law of the Land

Geographic and Environmental Framework

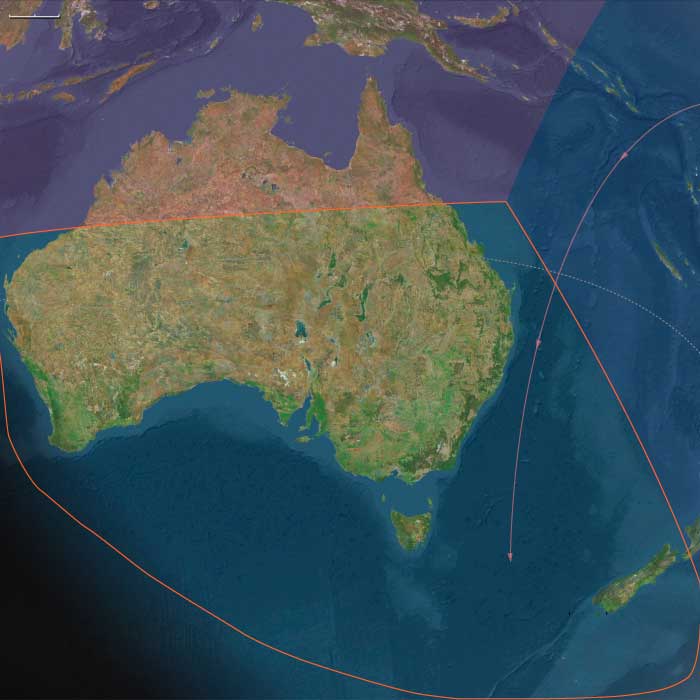

Australasia in the Lower Late Medieval Age spanned a vast temperate and tropical continuum—from the voyaging frontiers of South Polynesia to the fertile river basins of Southern Australia and the monsoon-driven coasts of Northern Australia.

The region’s islands and continents formed an intricate mosaic of ecosystems and lifeways:

-

Aotearoa (New Zealand) and its outlying islands (Chatham, Norfolk, Kermadec) stood at the cool, temperate edge of Polynesia, where new settlers adapted tropical horticulture to shorter growing seasons.

-

Southern Australia and Tasmania preserved long-established Aboriginal foraging systems rooted in ritual law and fire-managed landscapes.

-

Northern Australia and the Torres Strait Islands connected the Australian mainland to New Guinea, blending monsoon foraging, wetland hunting, and horticultural–maritime chiefdoms.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The onset of the Little Ice Age after c. 1300 CE brought cooler, wetter climates to the southern temperate zones and slightly drier variability to the north.

-

New Zealand: Shortened growing seasons and periodic frosts challenged taro and yam cultivation, prompting reliance on kūmara (sweet potato), fern root, and bracken.

-

Southern Australia and Tasmania: Temperature declines were modest; flexible fire-based foraging adjusted easily.

-

Northern Australia: Monsoon variability increased, but wetlands and reefs remained highly productive.

Across the region, communities responded with diversified subsistence, intensified exchange, and ceremonial frameworks that redistributed risk.

Societies and Political Developments

Aotearoa and the Southern Islands

East Polynesian voyagers reached Aotearoa around 1200–1300 CE, establishing dispersed horticultural hamlets and fortified pā. By the mid-14th century, sizeable iwi (tribes) and hapū (sub-tribes) emerged, anchored in canoe genealogies (Arawa, Tainui, Mataatua) that legitimized land and lineage.

On the Chatham Islands, settlers evolved into the Moriori, adapting to cooler climates with marine specialization and egalitarian governance.

Norfolk and Kermadec Islands remained small but vital outposts linked to Aotearoa through ritual and exchange.

Southern Australasia

In New Zealand’s South Island, Māori expansion created mixed economies: horticulture in northern valleys, hunting of moa, seals, and eels in southern zones—early expressions of Ngāi Tahu identity.

Across southern Australia and Tasmania, Aboriginal and Palawa societies maintained flexible kin-based networks, practicing firestick farming, riverine fishing, and seasonal migration between coasts, rivers, and uplands.

Large ceremonial gatherings along the Murray–Darling Basin reinforced intergroup alliances through exchange of ochre, greenstone, and ritual performances.

Northern Australia and the Torres Strait

In Arnhem Land and the Kimberley, clan societies ordered by the Dreaming maintained songline networks linking land, sky, and sea.

Cape York and Gulf populations held wet-season festivals and dry-season hunts, integrating multiple language groups.

Across the Torres Strait Islands, horticultural–maritime chiefdoms flourished—growing taro, yams, and bananas; cultivating reef fisheries; and trading with both Papua and Australia. Hereditary leaders (mamoose) presided over complex initiation and fertility rites.

Economy, Exchange, and Technology

Horticultural and Foraging Systems

-

Māori horticulture: Kūmara grown in storage pits and ridged fields; taro, yam, and gourds cultivated where possible.

-

Aboriginal Australia: Root crops, marsupials, and fish taken from managed landscapes shaped by controlled burning.

-

Tasmania: Littoral hunting and inland foraging for shellfish, seals, wallabies, and tubers.

-

Torres Strait: Mixed horticulture of taro, yam, banana, and sugarcane integrated with turtle and dugong fishing.

Trade and Interaction Networks

-

Polynesian linkages: Canoe routes connected Aotearoa with Norfolk and Kermadec Islands; stone tools and feathers exchanged among iwi.

-

Trans-Tasman circuits: Pounamu (greenstone) moved across New Zealand’s South Island; ochre and axes circulated across mainland Australia.

-

Torres Strait hub: The crucial conduit between New Guinea and Australia, transferring pearl shell, turtle shell, dugong tusks, canoes, and ceremonial goods.

-

Songlines and rivers: Functioned as spiritual and logistical corridors across the continent, binding far-flung societies through narrative geography.

Technology and Material Culture

-

Canoes: Double-hulled voyaging vessels in Aotearoa; large outrigger sailing craft in the Torres Strait; bark and dugout canoes for fishing across Australia.

-

Architecture: Māori whare and fortified pā; Aboriginal bark shelters and eel-trap villages; Torres Strait men’s houses for ceremony and governance.

-

Tools: Stone adzes, obsidian flakes, shell scrapers, wooden clubs, nets, and drums; artistry expressed in carving, feather ornamentation, and rock art.

Belief, Symbolism, and Law

Across Australasia, cosmology integrated environment, ancestry, and moral order.

-

Māori cosmology: Atua (deities) and canoe ancestors governed land tenure, warfare, and ritual. Tapu and manadefined sacred authority, mediated by tohunga.

-

Moriori belief: Peace-making and collective decision-making replaced hierarchical ritual, reflecting adaptation to isolation.

-

Aboriginal and Palawa Dreaming: Totemic ancestors shaped every landscape; song, dance, and art re-enacted their creation.

-

Torres Strait spirituality: Ancestral spirits of sea and sky embodied in masks and initiation cults; ceremonies linked warfare, fertility, and navigation.

Spiritual systems bound society to ecology—affirming stewardship through sacred law rather than centralized states.

Adaptation and Resilience

The peoples of Australasia met climatic and ecological challenges with ingenuity:

-

Māori diversified crops and fortified pā for defense amid resource pressure.

-

Moriori and island settlers emphasized maritime economies and cooperation.

-

Aboriginal Australians sustained mobility, fire management, and ritual governance to maintain balance.

-

Torres Strait Islanders combined horticulture and navigation, sustaining trade and diplomacy across seas.

Each community integrated environmental knowledge, ritual reciprocity, and flexible subsistence to ensure continuity through cooler centuries.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395 CE, Australasia had crystallized as a realm of parallel adaptation and enduring diversity:

-

Māori societies forged resilient iwi/hapū polities—fortified, horticultural, and ocean-connected.

-

Moriori demonstrated peaceful, marine-adapted lifeways born of isolation.

-

Aboriginal Australians and Palawa peoples maintained ancient Dreaming economies rooted in mobility and ecological law.

-

Torres Strait Islanders stood as cultural intermediaries between New Guinea and Australia, blending trade, ceremony, and cultivation.

Together, these societies defined Australasia as the meeting ground of voyagers and foragers, where tropical seafaring traditions met continental law, and where adaptation to climate, geography, and spirit produced one of humanity’s most enduring tapestries of ecological and cultural resilience.

South Polynesia (1252 – 1395 CE):

Aotearoa’s Settlement, Chatham Isolation, and Expanding Canoe Chiefdoms

Geographic and Environmental Context

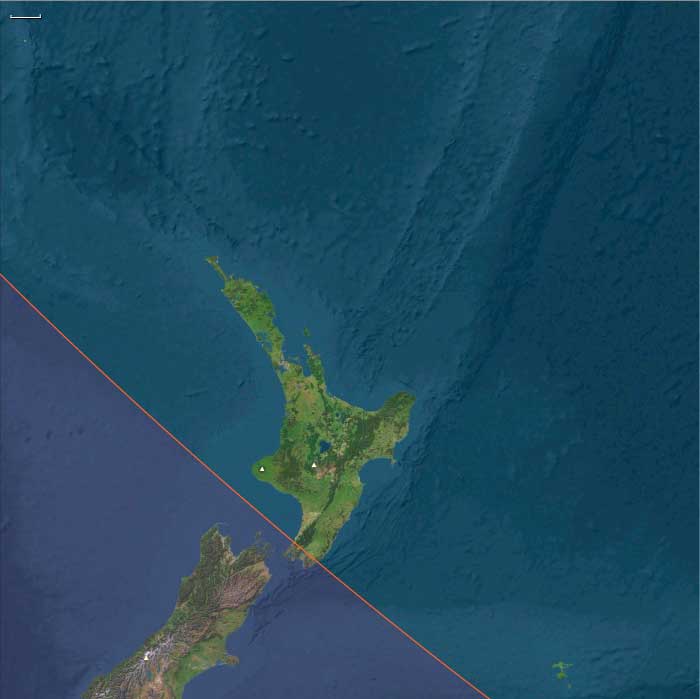

South Polynesia includes New Zealand’s North Island (except its southern coast), the Chatham Islands, Norfolk Island, and the Kermadec Islands—a temperate extension of the wider Polynesian world.

-

North Island (Aotearoa): volcanic uplands, fertile alluvial valleys, temperate forests, and extensive coasts with rich fisheries.

-

Chatham Islands: cooler, wind-swept, with limited forest and agriculture; communities relied on marine and seabird resources.

-

Norfolk and Kermadec Islands: small volcanic isles with fertile soils and fringing reefs, maintaining modest Polynesian horticultural economies.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The transition into the early Little Ice Age (after c. 1300 CE) brought cooler, wetter conditions in New Zealand.

-

Shorter growing seasons challenged tropical cultigens (taro, yam, breadfruit), encouraging diversification toward kūmara (sweet potato), fern root, and bracken gardens.

-

On the Chathams, cooler conditions limited gardening, favoring fishing, birding, and sealing.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Aotearoa (North Island):

East Polynesian settlers arrived c. 1200–1300 CE. By the mid-14th century, sizeable iwi (tribes) and hapū (sub-tribes) had formed. Canoe traditions (Arawa, Tainui, Mataatua, etc.) provided genealogical legitimacy and territorial identity. Settlement patterns combined fortified pā (hill forts) with dispersed horticultural hamlets. -

Chatham Islands:

Settlers diverged culturally into the Moriori, adapting to limited gardening by emphasizing fishing, sealing, and seabird harvests. Egalitarian councils replaced hierarchical Polynesian chiefly systems. -

Norfolk and Kermadec Islands:

Sparse settlements maintained Polynesian horticulture and fishing lifeways, linked by periodic canoe voyages to Aotearoa.

Economy and Trade

-

Aotearoa: Kūmara cultivation in northern valleys; smaller plots of taro, yam, and gourds where viable. Supplementary staples included fern-root, cabbage-tree root, and berries. Protein came from moa (declining by late 14th century), seals, fish, shellfish, and forest birds.

-

Chathams: Marine-centered economy of seals, seabirds, fish, and shellfish; only limited kūmara attempts.

-

Norfolk and Kermadecs: Mixed horticulture (taro, yams, kūmara), coconuts, and reef fishing.

-

Exchange: Canoe voyages connected offshore isles to Aotearoa’s coasts; greywacke and obsidian tools, feathers, and ritual valuables circulated.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Agriculture: Kūmara grown in storage pits and ridged fields; fern-root gardens on upland slopes.

-

Hunting & fishing: Large nets, hooks, traps, and bird snares; moa and seal hunts central in early settlement.

-

Architecture: Whare (timber-reed houses) and pā fortifications with ditches and palisades.

-

Canoes: Double-hulled voyaging canoes for inter-island travel; river and coastal craft for fishing and trade.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Canoe networks tied iwi settlements across Aotearoa, maintaining marriage and exchange ties.

Norfolk and Kermadec routes conveyed horticultural cultigens and stone tools.

The Chathams, after initial contact, grew increasingly isolated, developing distinctive lifeways.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Aotearoa Māori:

Cosmology centered on atua (deities), descent from canoe ancestors, and ritual specialists (tohunga). Tapu and mana structured land, leadership, and resource use. -

Moriori (Chathams):

Emphasized peace-making and collective governance, adapting rituals to marine environments. -

Sacred landscapes: Mountains, rivers, and forests remained infused with the presence of atua and canoe-ancestor narratives.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Aotearoa: Diversified food base—kūmara, fern-root, hunting, and fishing—buffered cooler conditions.

-

Chathams: Marine specialization ensured survival where crops failed.

-

Offshore islands: Maintained resilience through small-scale horticulture and exchange with Aotearoa.

-

Pā fortifications and inter-tribal alliances mitigated conflict and resource stress.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395 CE, South Polynesia had become a frontier of Polynesian adaptation:

-

Aotearoa Māori consolidated iwi and hapū identities around canoe genealogies, horticulture, and fortified settlements.

-

Moriori on the Chathams embodied a divergent, egalitarian, marine-adapted culture.

-

Norfolk and Kermadecs remained small but vital outposts linking South Polynesia to wider voyaging routes.

These transformations marked Polynesia’s bold expansion into temperate and subpolar zones—reshaping lifeways far from tropical origins.

Southern Australasia (1252 – 1395 CE):

Intensified Horticulture, Māori Expansion, and Tasmanian Foraging

Geographic and Environmental Context

Southern Australasia includes southern Australia (New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Tasmania, and southern Western Australia) together with New Zealand’s South Island and the southwestern coast of the North Island.

-

Southern Australia: Coastal plains, eucalyptus woodlands, and riverine corridors (Murray–Darling) sustained hunter-gatherer economies.

-

Tasmania: Cold-temperate island environments supported littoral hunting and seasonal inland foraging.

-

New Zealand (South Island and southwest North Island): Newly settled by East Polynesians, featuring fertile valleys, temperate forests, and abundant fisheries.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

After c. 1300, the onset of the Little Ice Age brought cooler, wetter conditions.

-

In New Zealand, shorter growing seasons stressed tropical crops; kūmara and fern-root became staples.

-

In Tasmania and southern Australia, flexible foraging economies adapted easily to climatic variability.

Societies and Political Developments

-

New Zealand Māori:

Settlement expanded through the 13th–14th centuries; iwi and hapū consolidated territories anchored in canoe ancestry. Fortified pā multiplied as populations grew and competition for fertile valleys increased. -

South Island Māori (Ngāi Tahu):

Blended northern horticulture with southern hunting—moa, seals, and eels—creating mixed economies. -

Tasmania (Palawa peoples):

Small kin bands maintained seasonal foraging rounds; firestick farming created mosaics of grassland and woodland. -

Southern Australia:

Riverine and wetland settlements fostered dense aggregation and ceremonial life. Trade in greenstone and ochre linked regions without central states.

Economy and Trade

-

Māori horticulture: Kūmara in storage pits and ridged fields; taro, gourds, and cabbage-tree roots supplemented diets.

-

Protein sources: Moa, seals, fish, eels, and birds. South Island groups relied heavily on preserved game.

-

Tasmania: Shellfish, seals, kangaroos, wallabies, and roots.

-

Southern Australia: Riverine fish, waterfowl, marsupials, tubers, and yams; semi-permanent eel aquaculture at Lake Condah.

-

Trade: Pounamu (greenstone) moved across the South Island; ochre and axes circulated across the mainland.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Māori: Double-hulled canoes for fishing and trade; pā fortifications with palisades, ditches, and terraces; stone adzes and shell tools.

-

Tasmanians: Bone awls, wooden spears, fiber nets, bark canoes; no hafted stone axes or fishhooks, but highly adaptive seasonal mobility.

-

Mainland Australians: Ground-edge axes, fish weirs, eel traps, and firestick farming for habitat renewal.

-

Architecture: Māori whare, Australian bark shelters, and Tasmanian windbreak huts.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Canoe circuits linked Māori settlements across islands, integrating gardens, hunting zones, and pā networks.

Pounamu trails spanned the Southern Alps.

Murray–Darling rivers and Tasmanian channels facilitated trade, ceremony, and kin exchange.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Māori: Mana (authority) and tapu (sacred restriction) structured life; tohunga mediated between atua and people; canoe genealogies legitimized land rights.

-

Tasmanians and Australians: Dreaming or Law tied spirits to land and totem animals; rock art, songs, and ritual gatherings renewed cosmic order.

-

Ceremonial exchange affirmed social bonds across linguistic and ecological zones.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Māori diversification buffered climatic stress; pā ensured defense during competition.

-

Aboriginal firestick farming maintained productive ecotones.

-

Tasmanian mobility evened resource variability.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395 CE, Southern Australasia displayed dual trajectories:

-

Māori societies had forged resilient iwi/hapū polities, blending horticulture, hunting, fortified pā, and canoe exchange.

-

Aboriginal Australians and Tasmanians sustained enduring foraging economies anchored in ritual law and ecological expertise.

Together they exemplified temperate adaptation—from Māori proto-chiefdoms to forager confederacies—each resilient under the shifting climates of the Little Ice Age.

Polynesian peoples who had migrated from nearby Tahiti to the southeast in the sixth century were the first settlers of the Cook Islands.

Eastern Polynesian speakers of the Malayo-Polynesian language family, in a subsequent wave of immigration, probably from the Marquesas or Cook Islands, begin to arrive in New Zealand in several waves of canoe voyages between 1250 and 1300, initiating human settlement of the last sizable landmass in the South Pacific.

The most current reliable evidence strongly indicates that initial settlement of New Zealand occurred around 1280 CE at the end of the medieval warm period.

The immigrants settle initially in the Otago region on the east coast of South Island.

The large (up to ten feet tall), flightless birds called moas provide their major food source.

The precise date at which the first inhabitants of New Zealand reached Otago and the extreme south (known to later Māori as Murihiku) remains uncertain.

Māori descend from a race of Polynesian sea-wanderers who, in some far-off age, moved from East Asia and Southeast Asia to the islands of the Pacific.

Tradition tells of their further journeys from Hawaiki to New Zealand, and some commentators have identified this homeland as Havai'i, an island in the Society Group.

Overpopulation, scarcity of food and civil war forced many of them to migrate once more, and New Zealand becomes their new home.

The fierce, belligerent newcomers establish fortified villages, engage in internecine warfare and practice cannibalism.

Northern Australia (1252 – 1395 CE):

Arnhem Land Ceremonies, Torres Strait Trade, and Wetland Hunters

Geographic and Environmental Context

Northern Australia includes the Kimberley, Arnhem Land, Cape York Peninsula, the Gulf of Carpentaria, and the Torres Strait Islands—a region of monsoon savannas, wetlands, reefs, and island chains where land and sea were inseparable.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The onset of the Little Ice Age (after c. 1300) slightly reduced rainfall and increased variability.

-

Coastal and wetland zones retained abundant fisheries, while inland foraging required seasonal mobility.

-

Cyclonic activity and sea-level stability shaped resource use along reefs and islands.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Arnhem Land & Kimberley:

Clan-based societies ordered by Dreaming songlines, linking ancestral beings to land and sky. Rock art traditions at sites such as Nawarla Gabarnmang and the Wandjina figures flourished. -

Cape York & Gulf Country:

Seasonal movement between coasts and uplands; large ceremonial gatherings (corroborees) reinforced kinship across languages. -

Torres Strait Islands:

Populations formed horticultural–maritime chiefdoms cultivating taro, yams, and bananas while maintaining reef fisheries. Hereditary chiefs (mamoose traditions) led complex initiation rituals and managed diplomacy with both Papuan and Aboriginal partners.

Economy and Trade

-

Mainland foraging: Kangaroos, wallabies, emus, reptiles, fish, shellfish, and edible roots.

-

Wetlands: Magpie geese, fish, and yams; controlled burning enhanced hunting grounds.

-

Torres Strait horticulture: Taro gardens, yam mounds, banana groves, and sugarcane.

-

Trade networks:

-

The Torres Strait served as the exchange hinge between Australia and New Guinea, trading pearl shell, dugong tusks, turtle shell, canoes, and stone axes.

-

Mainland routes circulated ochre, spear shafts, resin, and ceremonial goods across Arnhem Land and the Gulf.

-

Subsistence and Technology

-

Fishing: Dugout and bark canoes, nets, spears, and tidal traps.

-

Fire management: Seasonal burns maintained open hunting grounds and yam regeneration.

-

Torres Strait canoes: Large outrigger sailing craft carried cargo and passengers across island arcs.

-

Tools and art: Stone axes, shell scrapers, fiber nets, and ceremonial masks and drums for ritual display.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Songlines: Crossed Arnhem Land and Kimberley, guiding ceremony, navigation, and rights to land.

-

Torres Strait routes: Linked island clusters with Cape York and Papuan coasts, sustaining long-distance trade.

-

Cape York–Gulf trails: Seasonal passages tied coastal fisheries to inland game grounds.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Mainland Dreaming: Totemic beings created and ordered the world; ceremonies reenacted and renewed the Law.

-

Torres Strait cosmology: Initiation cults linked ancestral spirits with warfare and fertility; masks embodied sea and sky deities.

-

Ceremonial gatherings: Corroborees reinforced alliances, moral law, and ecological balance.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Mobility: Seasonal rounds across wetlands, savannas, and coasts ensured sustenance.

-

Portfolio economies: Hunting, fishing, and horticulture (in the Torres Strait) provided redundancy.

-

Firestick farming: Renewed pastures, concentrated game, and prevented catastrophic wildfires.

-

Trade: The Strait functioned as a resilience hub, enabling import and redistribution during shortages.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395 CE, Northern Australia embodied complementary adaptive strategies:

-

Mainland Aboriginal societies maintained deep continuity through Dreaming law, fire ecology, and ritual timekeeping.

-

Torres Strait Islanders developed horticultural–maritime chiefdoms that served as cultural and commercial intermediaries between New Guinea and Australia.

Together they exemplified the endurance of songline law and the vitality of the maritime trade frontier—systems that would continue to shape the region’s balance of land, sea, and spirit well into the ensuing centuries.

The earliest period of Māori settlement is known as the "Archaic", "Moahunter" or "Colonisation" period.

The eastern Polynesian ancestors of the Māori arrived in a forested land with abundant birdlife, including several now extinct moa species weighing from twenty to two hundred and fifty kilograms (forty to five hundred and fifty pounds).

Other species, also now extinct, included a swan, a goose and the giant Haast's Eagle, which preyed upon the moa.

Marine mammals, in particular seals, thronged the coasts, with coastal colonies much further north than today.

At the Waitaki river mouth, huge numbers of Moa bones estimated at twenty-nine thousand to ninety thousand birds have been located.

Further South, at the Shag River mouth at least six thousand moa were slaughtered over a relatively short period.

Archaeology has shown that the Otago Region was the node of Māori cultural development during this time, and the majority of archaic settlements were on or within ten kilometers (six miles) of the coast, though it was common to establish small temporary camps far inland.

Settlements ranged in size from forty people (e.g., Palliser Bay in Wellington) to three hundred to four hundred people, with forty buildings (e.g., Shag River (Waihemo)).

The best known and most extensively studied Archaic site is at Wairau Bar in the South Island.

The site is similar to eastern Polynesian nucleated villages.

Radio carbon dating shows it was occupied from about 1288 to 1300.

Due to tectonic forces, some of the Wairau Bar site is now underwater.

Work on the Wairau Bar skeletons in 2010 showed that life expectancy was very short.

The oldest skeleton being thirty-nine and most people dying in their twenties.

Most of the adults showed signs of dietary or infection stress.

Anaemia and arthritis were common.

Infections such as tuberculosis may have been present as the symptoms were present in several skeletons.

On average the adults were taller than other South Pacific people at 175 centimeters for males and 161 centimeters for females.

The millennia-long eastward migration of the oceanic Austronesian speakers ends in about 1300 with the arrival of the Maoris in New Zealand.

Archaeological and linguistic evidence (Sutton 1994) suggests that several waves of migration have come from Eastern Polynesia to New Zealand between 800 and 1300.

Māori oral history describes the arrival of ancestors from Hawaiki (a mythical homeland in tropical Polynesia) in large oceangoing canoes.

Migration accounts vary among tribes (iwi), whose members may identify with several waka in their genealogies or whakapapa.

No credible evidence exists of human settlement in New Zealand prior to the Polynesian voyagers; on the other hand, compelling evidence from archaeology, linguistics, and physical anthropology indicates that the first settlers came from East Polynesia and became the Māori.

The Māori have come to New Zealand as Eastern Polynesians voyaging, most likely, from the area of the Cook Islands or from the Society Islands, in seagoing canoes—possibly double-hulled and probably sail-rigged.

These Polynesian settlers probably arrive no later than about 1300.

The fierce, belligerent Tangata Whenua, “people of the land” (the so-called Classic Maori) establish fortified villages, engage in internecine warfare and practice cannibalism.

The Maori tribes are fully established in New Zealand's two large islands before the fourteenth century, by which time most of Oceania’s autocthonous inhabitants are in place.

Australasia (1396–1539 CE)

Gardens, Fires, and the Southern Ocean World

Geography & Environmental Context

Australasia in this age encompassed three interlinked southern realms: South Polynesia (New Zealand’s North Island, the Chatham, Norfolk, and Kermadec Islands), Southern Australasia (southern Australia, Tasmania, and New Zealand’s temperate South Island), and Northern Australia (the Kimberley, Arnhem Land, Cape York, and the Gulf of Carpentaria).

Across this vast region, landscapes ranged from New Zealand’s volcanic valleys and river plains to Australia’s open woodlands, desert margins, and tropical floodplains. To the south lay the westerly-swept Tasman Sea and the icy waters of the Southern Ocean, connecting temperate islands through seasonal migration and long coasts. Mountains, plains, and reefs framed human worlds defined by gardening, hunting, burning, and voyaging.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The early Little Ice Age brought cooler, more variable climates.

-

New Zealand: Shorter growing seasons restricted taro and yam cultivation, prompting adaptation of kumara(sweet potato) to cooler soils.

-

Southern Australia & Tasmania: Cooler, wetter decades alternated with drought, expanding alpine snow cover and reshaping fire regimes.

-

Northern Australia: Monsoons remained dominant but fluctuated in intensity; cyclones periodically reworked coasts and mangroves.

Overall, environmental conditions favored diversification—horticulture in the north and east, fire-managed foraging and hunting in the south and interior.

Subsistence & Settlement

Agricultural and foraging systems reached new levels of ecological refinement.

-

South Polynesia (New Zealand & outliers): Kumara, gourds, and taro gardens expanded in warmer valleys; fortified pā (hilltop villages) clustered around fertile soils and coasts. The Chathams, cooler and wind-swept, depended on fishing, fowling, and seal hunting.

-

Southern Australasia (Australia & Tasmania): Aboriginal fire-stick farming maintained patchwork grasslands, sustaining kangaroo, emu, and wallaby hunting. Fish traps such as Brewarrina and eel channels in Victoria exemplified aquatic engineering. In Tasmania, hunting, gathering, and coastal foraging supported mobile communities.

-

Northern Australia: Seasonal abundance structured life—floodplain fishing and waterfowl harvests in the wet, hunting and yam-gathering in the dry. Coastal peoples exploited reefs and mangroves year-round, maintaining semi-permanent camps at rich estuaries.

Technology & Material Culture

Technological innovation expressed ecological mastery.

-

New Zealand: Stone and greenstone (pounamu) adzes, carved canoes (waka), flax-fiber cloaks, and pāfortifications embodied the emerging Māori cultural complex.

-

Australia: Stone tools, nets, and bark canoes persisted, while fire remained a powerful shaping tool of the landscape. Fish traps, grindstones, and bone tools extended productivity.

-

Northern Australia: Dugout and bark canoes, fish spears, and woven baskets enabled estuarine and reef exploitation. Rock art in Arnhem Land and the Kimberley portrayed ancestral beings, marine life, and ceremony, marking continuity of the Dreaming.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Mobility linked landscapes and seas.

-

In New Zealand, waka voyaging between North and South Islands sustained kin ties and resource exchange; routes reached out to the Chathams, Norfolk, and Kermadecs.

-

In Australia, trading paths moved ochre, stone, and songlines across vast distances; coastal exchange connected shell ornaments and ritual objects between the Bight and Cape York.

-

Northern Australia interfaced with the wider Indo-Pacific: Torres Strait crossings brought Papuan exchange centuries before Europeans, and possible early contact with Macassan trepangers hinted at future maritime linkages.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Spiritual life united land, sea, and ancestry.

-

Māori traditions articulated kinship through whakapapa (genealogy) and sacred landscapes marked by marae(ceremonial courtyards) and carved meeting houses. Agricultural rites and warfare fused political power with fertility and remembrance.

-

Aboriginal Australians followed the Dreaming (Songlines)—ancestral pathways mapping creation and law across country. Ceremonial dances, fire rituals, and totemic obligations reaffirmed balance between people and place.

-

Northern traditions joined cosmology and ecology: bark painting, rock art, and initiation ceremonies tied communities to seasonal renewal, the monsoon cycle, and the ancestors’ realm.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Australasian societies displayed extraordinary ecological intelligence.

-

Horticultural innovation: Kumara adapted to cool New Zealand soils; dryland cultivation persisted on Norfolkand Kermadecs.

-

Fire management: Aboriginal burning regenerated grasslands, reduced catastrophic fires, and ensured hunting continuity.

-

Mobility and exchange: Seasonal movement and kin redistribution buffered scarcity, while ritual feasting maintained social cohesion.

-

Resource integration: Marine, forest, and agricultural zones were managed as single systems—spatially diverse yet socially cohesive.

Transition (to 1539 CE)

By 1539, Australasia formed a mosaic of interconnected but autonomous traditions: Māori horticultural chiefdoms rising in temperate islands; Aboriginal fire-managed ecologies sustaining the world’s oldest living cultures; and monsoonal hunter-fishers thriving in the continent’s north.

Across seas, estuaries, and mountains, people lived by renewal—of fire, crop, and ceremony. The region stood complete in its balance between abundance and restraint, its societies resilient under cooler skies and shifting rains. The southern-ocean world was fully peopled, richly symbolic, and ecologically integrated—unaware that distant sails, already rounding the Cape of Good Hope, would soon redraw its horizons.

South Polynesia (1396–1539 CE): Gardens, Canoes, and Sacred Landscapes

Geographic & Environmental Context

The subregion of South Polynesia includes New Zealand’s North Island (except its southern coast), the Chatham Islands, Norfolk Island, and the Kermadec Islands. These islands varied dramatically: New Zealand’s volcanic highlands and fertile river valleys contrasted with the smaller, wind-swept Chathams and Norfolk, while the Kermadecs offered rugged volcanic cones surrounded by productive seas. Coastal plains, estuaries, and fertile soils sustained agriculture, while offshore currents supported rich fisheries.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

This age coincided with the early centuries of the Little Ice Age. In New Zealand, cooler conditions shortened growing seasons for tropical crops such as taro and yam, pushing communities to adapt by intensifying kumara (sweet potato) cultivation in warmer valleys. The Chathams, further south and colder, were marginal for agriculture and relied heavily on fishing, fowling, and foraging. Climatic variability also shaped cyclonic storms in the Kermadecs and altered rainfall patterns on Norfolk, testing subsistence systems across the subregion.

Subsistence & Settlement

In New Zealand’s North Island, communities established extensive gardens of kumara, supplemented by gourds and taro in warmer areas, with hunting and fishing continuing as essential pursuits. Moa hunting was in steep decline and nearly extinct by this period, marking a major ecological shift. The Chathams supported subsistence through seal hunting, fishing, and seabird colonies, with little horticulture. Norfolk and the Kermadecs supported mixed gardening, coconuts, breadfruit, and reef fisheries, sustaining smaller communities. Settlements in New Zealand clustered around fertile soils and coastal resources, often fortified into pā (hillforts) reflecting competition and warfare.

Technology & Material Culture

Material culture reflected both continuity and innovation. In New Zealand, stone adzes, greenstone (pounamu) tools, and wooden weapons flourished, alongside canoe-building traditions suited to coastal voyaging. Fortifications (pā) reflected engineering skill, while finely carved wooden houses, ornaments, and ritual implements conveyed cosmological symbolism. Cloaks of flax fibers, adorned with feathers, were both practical and prestigious. In the Chathams, simpler material traditions prevailed, emphasizing fishing gear, nets, and birding technologies adapted to local ecology.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Voyaging routes tied the Kermadecs, Norfolk, and Chathams to New Zealand’s North Island, though sustained connections were limited by climatic challenges and distance. Coastal voyaging within New Zealand remained vibrant, enabling seasonal movement, trade, and political consolidation. Exchange networks circulated greenstone, obsidian, and other valuables, while alliances and rivalries linked tribal polities. Beyond Polynesia, long-distance voyaging to other Pacific archipelagos waned in this age, consolidating South Polynesia as a relatively self-contained sphere.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Cultural systems thrived. In New Zealand, Māori society emerged in distinct form, with tribal genealogies (whakapapa) anchoring identity, and pā fortifications, marae (ritual spaces), and carved houses embodying sacred authority. Ritual life centered on agriculture (especially kumara planting and harvest), warfare, and ancestral veneration. Oral traditions preserved cosmologies, genealogies, and mythic histories in chant and story. In the Chathams, cultural life emphasized marine and avian resources, with cosmologies tied to sea and sky. Symbolism of canoes, birds, and ancestors infused art, ritual, and identity across the subregion.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Communities displayed resilience to Little Ice Age cooling. In New Zealand, crop specialization (kumara) and careful soil management sustained populations despite shorter growing seasons. Moa extinction prompted intensified fishing, birding, and cultivation. In the Chathams, resilience lay in diversified exploitation of seabirds, fish, and seals. Social adaptations—redistribution through kin networks, fortified settlements, and seasonal movement—mitigated environmental stress.

Transition

By 1539 CE, South Polynesia had become a dynamic cultural landscape. New Zealand’s North Island supported growing Māori populations, fortified villages, and distinctive ritual life; the Chathams and outlying islands adapted subsistence to harsher climates. While long-distance voyaging beyond the subregion had diminished, South Polynesia was vibrant, resilient, and culturally distinct, poised on the eve of transformative contact in the centuries to come.