East Melanesia (820 – 963 CE): Island …

Years: 820 - 963

East Melanesia (820 – 963 CE): Island Chiefdoms, Grade Societies, and Canoe Exchange

Geographic and Environmental Context

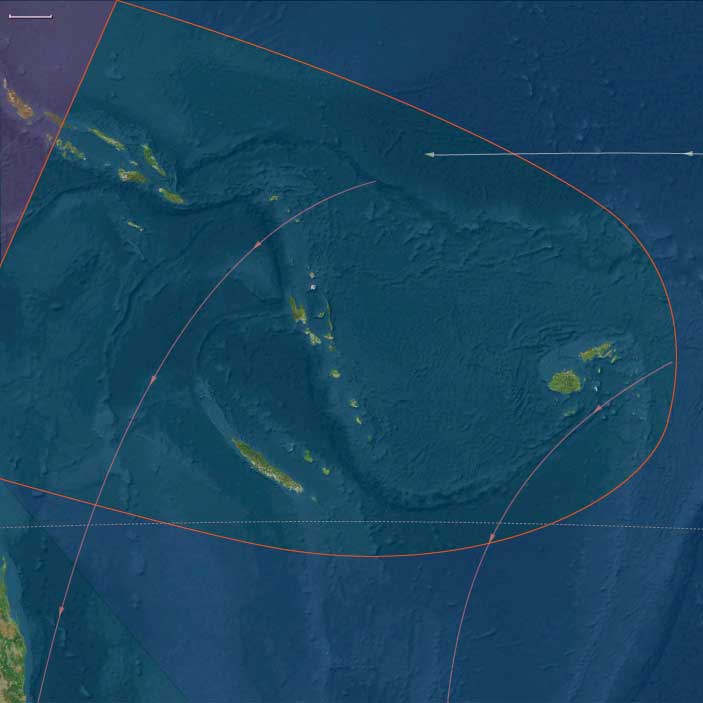

East Melanesia includes Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia, and the Solomon Islands (excluding Bougainville, which belongs to West Melanesia).

-

High volcanic islands (Espiritu Santo, Efate, Tanna, Guadalcanal, Malaita, Viti Levu, Vanua Levu) provided fertile uplands, deep valleys, and fringing reefs.

-

Raised limestone islands and low atolls (e.g., parts of New Caledonia and the outer Solomons) offered narrower soils but rich lagoons.

-

Narrow coastal shelves, steep interior ridges, and reef passes segmented communities into clustered polities linked by canoe routes.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

A warm, maritime regime prevailed; the approach to the Medieval Warm Period brought slightly longer growing seasons.

-

Cyclones and drought pulses periodically stressed outer-island gardens and reef fisheries, but high-island watersheds buffered shortages.

-

Orographic rainfall on windward slopes sustained taro terraces and irrigated valley gardens.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Vanuatu: Island polities organized around grade-taking societies (e.g., nimangki, sukwe), where men advanced through ritual payments—especially pig tusks—to gain prestige and ritual authority. Leadership was competitive and distributed, but influential ritual specialists and “big-men” coordinated feasts, land, and conflict mediation.

-

Fiji: Coastal and riverine chiefdoms crystallized along fertile deltas of Viti Levu and Vanua Levu; inland, defensible ridge settlements emerged on spurs above garden lands. Kin-based councils managed irrigation ditches, fishing rights, and craft labor; alliances were sealed by marriage, exchange, and ceremonial hospitality.

-

Solomon Islands (except Bougainville): Clan-based chiefdoms on Guadalcanal, Malaita, Makira, and Isabel balanced coastal fishing villages with interior garden hamlets. Ritual houses anchored political life; dispute-settlement and compensation payments stabilized inter-lineage relations.

-

New Caledonia: Upland horticultural communities (later Kanak heartlands) cultivated yam and taro in ridged garden systems; authority resided in senior lineages that organized seasonal labor and ritual.

Economy and Trade

-

Horticulture: yams, taro, bananas, and breadfruit formed the staple base; giant swamp taro and taro terraces supported valley populations; pigs were critical wealth and feast animals.

-

Reef and lagoon fisheries: nearshore netting, line fishing, and shellfish collecting yielded steady protein; smoked and dried fish traveled as exchange goods.

-

Exchange networks: inter-island canoe voyages moved shell valuables, fine mats, adze stone, sennit cordage, red-feather ornaments, and cured pork. High islands funneled stone and forest products to atolls; atolls returned salt fish, coconut cordage, and shell.

-

Cross-cultural corridors: eastern Fiji interfaced with Tonga–Samoa to the east, while northern Vanuatu–Solomons touched the Micronesian periphery, transmitting canoe forms, ornaments, and ritual motifs.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Garden engineering: stone alignments and, in favored valleys, irrigated taro pondfields stabilized yields; mulching, mounding, and fallow rotations preserved soil fertility.

-

Animal management: pigs were fattened for grade rituals and compensation payments; chickens supplemented diets.

-

Canoe technology: outrigger sailing canoes (single and double) with crab-claw or spritsails crossed windward channels; shell and bone tools aided hull shaping; breadfruit and sennit lashings bound planks.

-

Ceramics: post-Lapita ceramic traditions persisted differentially (e.g., in parts of Fiji and Vanuatu), serving cooking and storage needs; stone adzes remained essential for arboriculture and canoe building.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Reef-pass and leeward-coast sailing lanes joined island clusters (e.g., Santo–Efate–Tanna, Viti Levu–Lau, Guadalcanal–Malaita–Makira).

-

Wind-season calendars structured long voyages: downwind movements during trade-wind peaks; inter-island visits timed to harvests and ceremonial cycles.

-

Ceremonial circuits linked grade promotions, marriage exchanges, and peace-making feasts across neighboring islands.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Ancestral power (mana) infused land, pigs, and shell valuables; tabu prescriptions governed access to sacred groves, stones, and fishing grounds.

-

Ritual houses displayed clan emblems and ancestor relics; drums, slit-gongs, and conch trumpets synchronized feasts and grade rites.

-

Pig-tusk symbolism and shell-ring valuables indexed rank and ritual achievement; exchange enacted social bonds and cosmological balance.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Multi-ecosystem subsistence—gardens + reef + lagoon + upland foraging—spread risk against cyclones and drought.

-

Ritual redistribution (grade feasts, compensation payments) reallocated surplus to stressed communities, stabilizing alliances.

-

Settlement flexibility—coastal hamlets paired with defensible ridge sites—reduced vulnerability to raid and sudden resource failure.

-

Inter-island reciprocity ensured salt, cordage, adze stone, and ceremonial goods moved where needed.

Long-Term Significance

By 963 CE, East Melanesia sustained stable, ritually integrated chiefdoms:

-

Vanuatu’s grade societies transformed pigs and shell valuables into political authority and social cohesion.

-

Fiji consolidated coastal–inland networks supported by irrigated valleys and defensible ridge settlements.

-

Solomon Islands and New Caledonia balanced lagoon fisheries with yam/taro horticulture under lineage leadership.

These systems formed the institutional and economic platform for later fortified hill settlements, expanded canoe exchange, and the intensifying Fiji–Vanuatu–Solomons interaction sphere in the following age.