East Asia (820 – 963 CE): Tang …

Years: 820 - 963

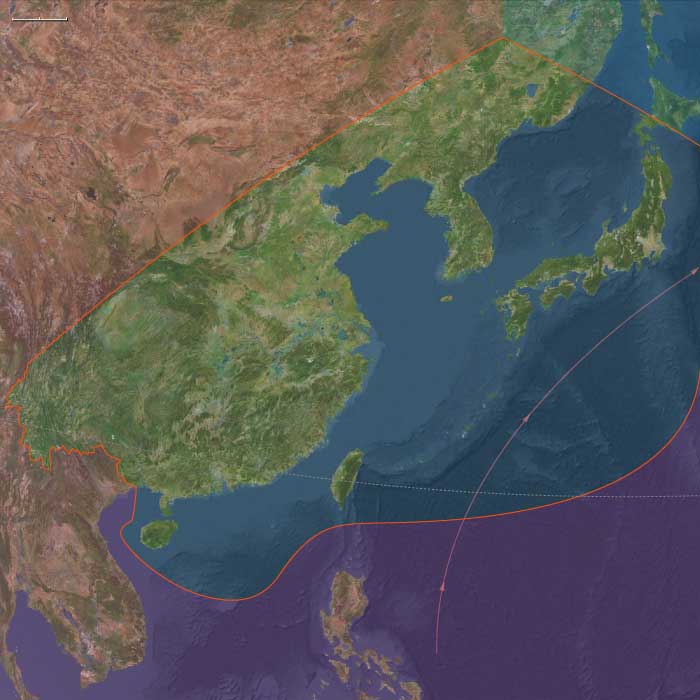

East Asia (820 – 963 CE): Tang Twilight, Tibetan Fragmentation, and the Maritime–Steppe Divide

Geographic and Environmental Context

East Asia between 820 and 963 CE stretched from the Pacific coastlands of Japan, Korea, and southern China to the mountain–desert worlds of Tibet, Xinjiang, and Mongolia.

It divided naturally into two great zones:

-

Maritime East Asia, encompassing China’s southern provinces, Korea, Japan, and Taiwan, where wet-rice agriculture and seaborne commerce shaped life.

-

Upper East Asia, including Tibet, Mongolia, and the western highlands of China (Xinjiang, Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia)—the upland and steppe frontier linking East and Central Asia.

The age witnessed the end of the Tang Dynasty, the dissolution of the Tibetan Empire, and the ascent of new polities—Goryeo in Korea, Heian Japan, and the frontier states of Nanzhao and the Khitan.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

A relatively stable late-Holocene climate supported demographic and agrarian growth:

-

In southern China, warm, humid conditions expanded rice cultivation across the Yangtze and Sichuan basins.

-

The Tibetan Plateau and northern steppes remained cold and arid, favoring pastoral mobility.

-

Periodic droughts in the Tarim Basin and steppe belt triggered migration and warfare.

-

Along the coasts, monsoon predictability sustained maritime trade and coastal urbanization.

Despite political upheavals, the region’s ecological base remained robust.

Societies and Political Developments

Maritime East Asia: From Tang to the Heian Zenith

-

China (Tang 618–907): Southern prefectures (Fujian, Guangdong) prospered through rice and maritime trade. Tang’s authority collapsed amid rebellion and provincial warlordism; by 907, China fragmented into the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms.

-

In the south, Yangtze and Sichuan economies ensured continued wealth under autonomous regimes.

-

Frontier states like Nanzhao (Yunnan, 738–902) resisted Tang power, linking to Southeast Asia.

-

Northeastern garrisons in Liaoning and Jilin fell to Khitan and Mohe incursions.

-

-

Korea: The Unified Silla kingdom waned after centuries of stability; internal unrest led to Goryeo’s foundation in 918, absorbing Silla by 935.

-

Japan: Under Heian rule (794–1185), the Fujiwara clan dominated court politics. The creation of kana writing fostered vernacular literature (Kokinshū, Tale of Genji foundations). Provinces grew increasingly autonomous, foreshadowing later warrior rule.

-

Taiwan: Austronesian-speaking communities cultivated taro and millet, fished coasts, and traded sporadically with Luzon and Fujian, remaining outside major state systems.

Upper East Asia: Fragmentation and Frontier Power

-

Tibet: Once a trans-Himalayan empire, Tibet fragmented after Langdarma’s assassination (842). Regional warlords and monasteries divided authority; Buddhist renewal began in western and eastern enclaves.

-

Mongolia and the Northern Steppes: Following the fall of the Uyghur Khaganate (840), Turkic and Mongolic tribes reorganized into shifting confederations; horse-trade diplomacy tied them to China and Central Asia.

-

Xinjiang and Gansu: Chinese retreat left oases like Khotan, Turfan, and Dunhuang under local Buddhist rulers and Uyghur refugees, who maintained Silk Road commerce.

-

The Hexi Corridor became a contested frontier between Chinese successor states, Tibetans, and steppe tribes.

-

Khitan and Mohe: In Manchuria, the Khitan built the foundation for the Liao dynasty (907–1125), while Mohe clans in Heilongjiang forged links to emerging Jurchen lineages.

Economy and Trade

-

Agrarian bases: Yangtze, Sichuan, and southern Chinese plains achieved major rice surpluses; riverine transport via canals supported dense markets.

-

Oasis economies: Wheat, barley, grapes, and cotton sustained Tarim Basin polities; irrigation canals and qanats extended arable belts.

-

Pastoralism: Yaks, horses, and camels dominated plateau and steppe economies; trade of hides, wool, and livestock offset scarce grain.

-

Maritime commerce: Southern Chinese ports, Guangzhou and Quanzhou, became key nodes linking India, Arabia, and East Africa.

-

Overland exchange: Silk, jade, and porcelain moved westward; silver, glass, and horses returned from Central Asia.

Despite Tang’s fall, economic integration deepened through overlapping sea and land networks.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Irrigation and rice terraces transformed southern landscapes.

-

Gunpowder and woodblock printing appeared in Tang–post-Tang China, reshaping military and intellectual life.

-

Silk and porcelain industries expanded, establishing enduring trade commodities.

-

Mounted warfare and composite bows defined steppe armies.

-

Buddhist monasteries doubled as banks, granaries, and literacy centers.

-

Navigation advanced with the magnetic compass’s proto-forms and larger oceangoing junks.

Technological vitality offset political fragmentation.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Silk Road: The Tarim–Hexi–Chang’an axis remained vital, though fragmented among regional warlords and oasis kings.

-

Maritime Routes: Chinese, Arab, and Southeast Asian ships plied between the South China Sea and Indian Ocean, creating multicultural ports.

-

Tibetan Passes: Trade through Lhasa–Kathmandu–Patna connected Inner Asia to South Asia’s Buddhist centers.

-

Steppe Roads: Nomadic confederations maintained east–west corridors across Mongolia and north Manchuria.

These arteries linked the economies and religions of three continents.

Belief and Symbolism

-

China and Nanzhao: Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism intertwined; Chan (Zen) Buddhism matured.

-

Tibet: Buddhist revival replaced imperial cults; monasteries became both spiritual and political fortresses.

-

Steppes: Shamanic traditions honored sky and ancestor spirits; Manichaeism and Nestorian Christianity persisted among Uyghurs.

-

Korea and Japan: Buddhism flourished; Confucian codes regulated court ethics; Shinto remained vital in Japan’s ritual life.

-

Taiwan: Austronesian animism and ancestor worship persisted, integrated with sea rituals.

Cross-cultural synthesis was the hallmark of the age—faiths traveled the same routes as silk and spices.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Agrarian south absorbed population and wealth after northern turmoil.

-

Steppe and plateau nomads survived climate variability through mobility and herding diversity.

-

Oasis fortification and caravan networks ensured prosperity amid shifting powers.

-

Maritime centers adapted to trade realignments, drawing new wealth from sea routes as land routes faltered.

-

Cultural patronage in Heian Japan and Goryeo Korea preserved continuity through aesthetic and spiritual investment.

Long-Term Significance

By 963 CE, East Asia had entered a transitional epoch of fragmentation and resilience:

-

China’s Tang empire had fallen, yet its agrarian heartlands and ports remained engines of prosperity.

-

Nanzhao and Khitan frontier powers foreshadowed new dynastic orders.

-

Tibet fragmented but laid the groundwork for monastic renaissance.

-

Korea unified anew under Goryeo; Japan reached cultural refinement in the Heian age; Taiwan’s Austronesians remained vital links in South China Sea voyaging.

From the steppe’s shifting alliances to the Heian court’s poetry, this was an age of continuity through transformation—the twilight of old empires and the dawn of regional autonomies that would define East Asia’s medieval heart.

Lower East Asia (with civilization) ©2024-25 Electric Prism, Inc. All rights reserved.

Groups

- Austronesian peoples

- Confucianists

- Shinto

- Buddhism

- Taoism

- Mohe people

- Khitan people

- Chaná

- Buddhists, Zen or Chán

- Chinese Empire, Tang Dynasty

- Silla, Unified or Later

- Balhae (Bohai, or Pohai), Kingdom of

- Nanzhao, or Nanchao, Bai Kingdom of

- Japan, Heian Period

- Hubaekje

- Taebong

- Taebong

- Liao Dynasty, or Khitan Empire

- Wuyue, or Wu-Yüeh, Kingdom of

- Min

- Goryeo

- Tang, Southern

- Chinese Empire, Pei (Northern) Song Dynasty

Topics

Commodoties

- Fish and game

- Hides and feathers

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Textiles

- Ceramics

- Strategic metals

- Aroma compounds

- Spices