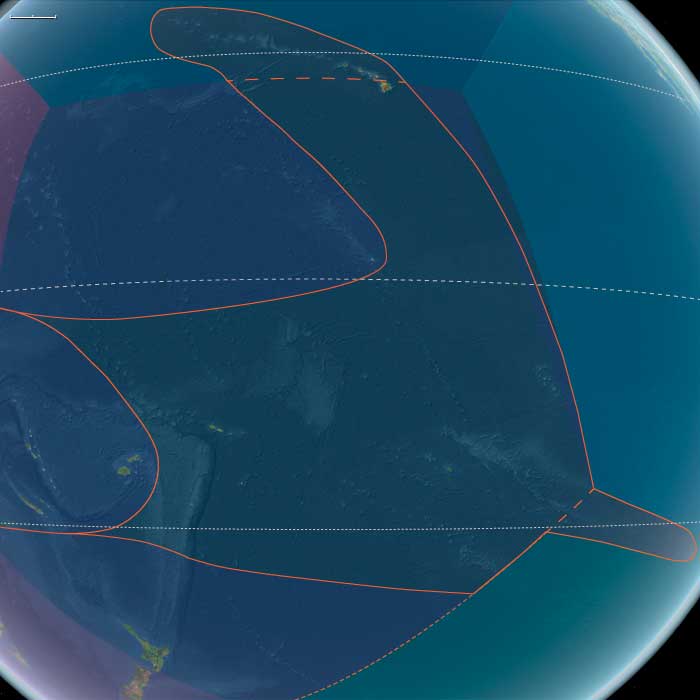

North Polynesia (909 BCE – 819 CE): …

Years: 909BCE - 819

North Polynesia (909 BCE – 819 CE): Proto-Contact Horizons — Reconnaissance Voyages and Ecological Baseline

Geographic & Environmental Context

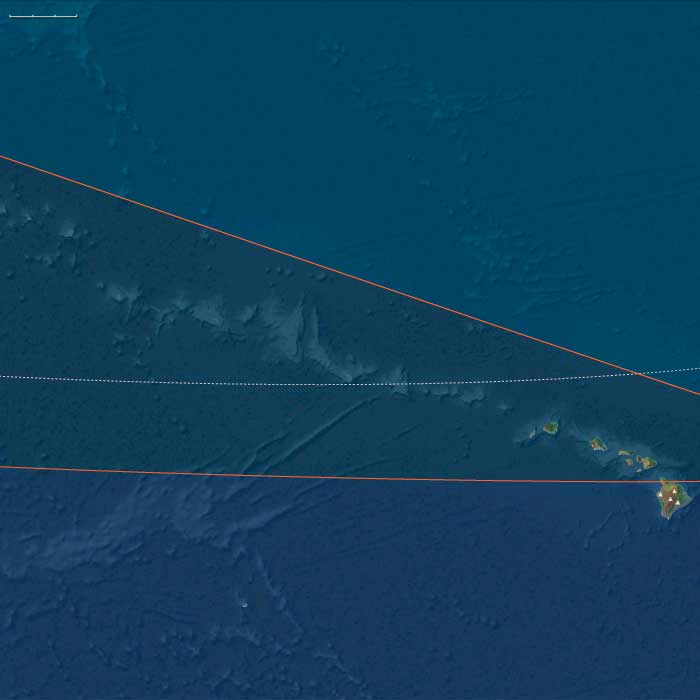

North Polynesia includes the Hawaiian Islands chain except Hawaiʻi Island (the Big Island) — principally Oʻahu, Maui, Kauaʻi, Molokaʻi, Lānaʻi, Niʻihau — plus Midway Atoll.

-

Anchors: Windward Oʻahu–Kauaʻi reef passes and fresh-watered valleys; Maui Nui lee bays (canoe landfalls); Midway as a remote atoll far to the northwest.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Slightly cooler first-millennium swings; trades remained reliable; winter swell seasons punctuated long-range voyaging windows.

Societies & Voyaging (Approach Phase)

-

In East/West Polynesia beyond this subregion, voyaging guilds perfected star compasses, swell-reading, and bird-pathfinding.

-

Probable reconnaissance or rare landfalls reached the Hawaiian high islands by the late first millennium CE (debated), yet enduring settlement most likely post-900–1000 CE.

Ecological Baseline at Threshold of Settlement

-

Pristine forests on valley floors and ridges; reef-lagoon systems at peak diversity; seabird rookeries across offshore stacks; no introduced mammals (rats, pigs, dogs) yet.

-

Streams ran clear; wetlands unmodified—ideal templates for later loʻi kalo (irrigated taro pondfields) and loko iʻa (fishponds).

Transition Toward the Medieval Period

By 819 CE, North Polynesia stood on the cusp: the islands were still uninhabited, but Polynesian voyaging capacity and wayfinding knowledge had matured to the point that permanent colonization would follow in the 10th–12th centuries, inaugurating the engineered ridge-to-reef societies documented in our later-age entries.

Groups

Commodoties

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 6 events out of 6 total

Driven from there by armed, aggressive neighbors, they settle for a while south of Lake Winnipeg in present Manitoba.

Later the people move to the Devil's Lake region of North Dakota before the Crow split from the Hidatsa and move westward.

The Crow have largely pushed westward due to intrusion and influx of the Cheyenne and subsequently the Sioux, also known as the Lakota.

To acquire control of their new territory, they war against Shoshone bands (called Bikkaashe—"People of the Grass Lodges"), and drive them westward.

They ally with local Kiowa and Kiowa Apache bands.

The Algonquian-speaking Blackfeet in the North and a branch of the Uto-Aztecan Shoshone in the South are the only non-cultivators on the Great Plains at the time of Contact.

The Blackfeet had previously occupied the forests above Lake Winnipeg; the southern Shoshone, eventually to be known as the Comanches, had formerly inhabited the region around Utah’s Great Salt Lake.

Semi-nomadic villagers and farmers along the Missouri may include the Siouan-speaking Mandans and Hidatsa.

Other early Plains agriculturists migrating north from present Louisiana include the ancestors of the Caddo, Wichita and Pawnee, as well as the Arikara (who will later separate from the Pawnee in the same manner as will the Absaroke, or Crow, from the Hidatsa).

Gulf and Western North America (1696–1707 CE): Indigenous Migrations, Colonial Expansion, and Cultural Exchange

Indigenous Peoples and Horse Culture on the Plains

By the late seventeenth century, diverse indigenous groups occupied distinct ecological niches across the Great Plains. The Algonquian-speaking Blackfeet, having migrated from the forests north of Lake Winnipeg, and the Uto-Aztecan-speaking southern Shoshone—who would become known as the Comanches after migrating from around Utah’s Great Salt Lake—were the only non-agricultural groups in this expansive region.

Agricultural tribes including the Mandan and Hidatsa had established semi-permanent villages along the Missouri River. Other Plains agriculturists, notably ancestors of the Caddo, Wichita, Pawnee, and the Arikara (the latter having recently diverged from the Pawnee), maintained village-based agriculture while gradually adopting the emerging equestrian culture.

Kiowas, primarily residing in northern Texas, Oklahoma, and eastern New Mexico, facilitated the spread of equestrian culture by trading horses to the Wichita, and later to the Cheyenne and Arapaho peoples. Similarly, the Utes traded horses to the Wyoming-based Shoshoni, who then passed these horses on to the recently separated Absaroke (Crow) and tribes of the southern Columbia Plateau, including the Nez Perce, Cayuse, and Palouse.

French and Spanish Colonial Rivalries

European claims in North America intensified, with France, Spain, and England consolidating their territories and competing fiercely. French explorers, notably Jean Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, joined his brother Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville to establish the colony of Louisiana. In 1699, they explored the Gulf of Mexico coast, discovering the Chandeleur Islands, Cat Island, and Ship Island, eventually ascending the Mississippi River to present-day Baton Rouge and False River.

Iberville founded the colony's first settlement, Fort Maurepas (present-day Ocean Springs, Mississippi), appointing Sauvolle de la Villantry as governor and Bienville as his lieutenant. Following Iberville’s return to France, Bienville established Fort de la Boulaye in 1700 on the Mississippi River and assumed governance after Sauvolle's death in 1701, initiating the first of his four terms as governor of Louisiana.

In response, Spain reinforced its Gulf Coast presence by establishing a garrison at Pensacola in 1696, setting the foundation for Florida's future capital. Meanwhile, in present-day New Orleans, natives had already established a critical portage between the Mississippi River and Bayou St. John (Bayouk Choupique), leading into Lake Pontchartrain. The integration of native and French settlements around this strategic portage laid the groundwork for what would eventually become the city of New Orleans, a pivotal economic and cultural hub.

Cultural and Religious Encounters in the Lower Mississippi Valley

French Catholic missionaries arrived among the lower Mississippi tribes, including the Taensa, Tunica, and Natchez, around 1699. These tribes, maintaining advanced agricultural societies and sophisticated ceremonial traditions, lived in significant villages featuring large structures often described by Europeans as earth-walled buildings, likely constructed of wattle-and-daub and cane mats.

The Taensa, noted for hierarchical social structures and complex religious practices involving ceremonial sacrifice, experienced devastating losses from European-introduced smallpox around 1700. Continuous raids by the Yazoo and Chickasaw, seeking captives for the English slave trade, further pressured the Taensa, who eventually relocated southwards and became embroiled in conflicts with other indigenous groups, including the Bayogoula and Houma.

Similarly, the French established missions among the Tunica and neighboring tribes (Koroa, Yazoo, Mosopelea) near the mouth of the Yazoo River around 1700. These tribes were distinctive for their complex religious practices and economic roles as middlemen in salt trade between Caddoan groups and the French settlers. During this era, the Chickasaw intensified slave raids, significantly impacting the Tunica, Taensa, and Quapaw populations along the lower Mississippi.

English-Spanish Conflicts in Florida

The early years of Queen Anne’s War saw intense English-Spanish rivalries, notably the English capture and burning of the Spanish town of St. Augustine, Florida in 1702. Although the main fortress withstood English assault, the surrounding settlement suffered extensive damage, marking the campaign as an English military failure. However, these hostilities devastated the Spanish mission system in Florida, culminating tragically in the Apalachee Massacre of 1704, effectively decimating the Apalachee tribe and destabilizing Spanish influence in the region.

Formation and Migration of the Crow Tribe

A distinct group from the Hidatsa villages along the Knife and Heart Rivers (present-day North Dakota) migrated westward between 1675 and 1700. Settling along the lower Yellowstone River in present-day Montana, these "proto-Crow" established initial residences primarily in tipis, indicating early stages of their transformation into a buffalo-hunting society. The Crow maintained connections and cultural exchanges with neighboring tribes such as the Kiowa and Arapaho, with whom they shared significant ceremonial practices and sacred objects, including the powerful Tai-may figure central to the Kiowa Sun Dance.

Key Historical Developments

-

French establishment of the Louisiana colony and early settlements (Fort Maurepas, Fort de la Boulaye).

-

Spanish response through fortified settlements at Pensacola.

-

Cultural and religious exchanges and conflicts among indigenous tribes in the Lower Mississippi Valley.

-

Intensification of slave raids and intertribal conflicts triggered by European demand.

-

English-Spanish military confrontations severely impacting Florida's indigenous communities and Spanish colonial infrastructure.

-

Formation and migration of the Crow tribe and cultural exchanges among Plains tribes.

Long-Term Consequences and Historical Significance

The era 1696–1707 marked intensified European rivalries, indigenous cultural adaptations, and significant demographic shifts due to disease, warfare, and slave raiding. These developments critically reshaped the sociopolitical landscape, laying the foundations for subsequent European territorial claims and indigenous responses across Gulf and Western North America.

Gulf and Western North America (1708–1719 CE): Equestrian Cultures, Indigenous Slave Trade, and Colonial Competition

Transformation and Expansion of Horse Cultures

By the early 1700s, the Arapaho had fully integrated horses into their society, dramatically transforming their way of life. Previously sedentary agriculturalists, the Arapaho became nomadic hunters, leveraging horses to increase their hunting efficiency and territorial range across the Great Plains.

Concurrently, groups of Shoshone moved southeast from present-day Wyoming and Utah, gradually becoming the feared Comanche, renowned for their exceptional horsemanship. The Comanche emerged as a dominant equestrian power, significantly shaping Plains culture. Their skill with horses allowed them to assert dominance over expansive territories, particularly in present-day Texas, profoundly affecting interactions with European colonizers and neighboring indigenous tribes.

Colonial Rivalries and the Indigenous Slave Trade

During this period, the slave trade involving indigenous captives intensified dramatically, becoming the most profitable enterprise between Native American groups in the Lower Mississippi Valley and the European colonies. The English had long conducted this trade from their colonies, notably South Carolina, but by the early eighteenth century, the French established their own competitive networks, exacerbating intertribal warfare.

Many indigenous groups, seeking to maximize advantages, cultivated relationships with both French and English traders, fostering internal divisions. Among the Natchez, pro-French villages included the Grand Village, Flour, and Tioux, strategically situated near the Mississippi River, while pro-English villages such as White Apple, Jenzenaque, and Grigra positioned themselves closer to the Chickasaw and English trade networks. The differing alliances frequently fueled hostilities, with White Apple often central to conflicts involving the Natchez and French.

Indigenous Alliances and European Influence

In the Southern Plains and Mississippi regions, the French and Spanish consolidated colonial holdings. The French expanded their influence up the Mississippi River, establishing Fort Maurepas and later Fort de la Boulaye under the leadership of Jean Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville. Bienville solidified French governance in Louisiana, strategically positioning the French colony to rival Spanish interests.

Meanwhile, in Florida, conflict during Queen Anne’s War culminated in the English capturing and burning the Spanish settlement at St. Augustine in 1702. Although the Spanish fortress withstood the attack, the devastation of surrounding areas severely undermined the Spanish mission system. The resultant destruction, notably the Apalachee Massacre of 1704, decimated indigenous populations and crippled Spanish colonial efforts.

Cultural Developments among the Crow and Kiowa

Between 1708 and 1719, the Crow people, having recently separated from their Hidatsa kin, continued to develop as a distinct buffalo-hunting society. Interactions with neighboring tribes such as the Kiowa fostered cultural exchanges, including the sharing of ceremonial objects and rituals. The sacred Tai-may figure, integral to Kiowa ceremonial life, traces its origins to these exchanges, underscoring the interconnectedness of Plains tribes.

Key Historical Developments

-

Rapid adoption and transformation of equestrian culture among the Arapaho and Comanche.

-

Intensification of indigenous slave trading networks driven by European colonial competition.

-

Strategic positioning and rivalry between French and English colonial powers, influencing indigenous alliances and conflicts.

-

Devastation and decline of Spanish missions and indigenous populations in Florida due to English military actions.

-

Continued cultural and ceremonial exchanges among Plains tribes, notably between the Crow and Kiowa.

Long-Term Consequences and Historical Significance

The period from 1708 to 1719 significantly reshaped the socio-political and cultural dynamics across Gulf and Western North America. Indigenous societies rapidly adapted to equestrianism, fundamentally altering regional power structures and lifestyles. The escalation of the indigenous slave trade, exacerbated by European colonial competition, intensified intertribal warfare and demographic shifts, laying the groundwork for future conflicts and alliances.

Gulf and Western North America (1720–1731 CE): Indigenous Alliances, European Expansion, and Tribal Migrations

Indigenous Migrations and Cultural Transformations

The Cheyenne become the first of the later Plains tribes to enter the Black Hills and Powder River Country, where they introduce horses to the Lakota around 1730. Pressure from migrating Lakota and Ojibwe pushes the Cheyenne further west, subsequently displacing the Kiowa further south.

The Arapaho, having moved farther south, split into Northern and Southern groups, establishing expansive territories across Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Oklahoma, and Kansas. A significant faction of Arapaho separates, becoming known as the Gros Ventre (or Atsina). Despite linguistic and cultural similarities, the Gros Ventre are viewed as inferior by their Arapaho kin.

Expansion of European Colonial Influence

France intensifies its colonial efforts in Louisiana, spreading settlements along the Mississippi River and its tributaries from New Orleans northward to the Illinois Country. Recognizing the strategic importance of the Mississippi River, France formally designates New Orleans as the colony's capital in 1722. German settlers, brought by John Law's Company of the Indies, establish communities along the "German Coast" in the early 1720s. When the company collapses in 1731, these settlers transition to independent landowners.

The Spanish, meanwhile, reduce their military presence in East Texas in the late 1720s, relocating vulnerable missions to San Antonio and intensifying their conflict with the Lipan Apache, who transfer their enmity toward Spain. In response, the Spanish crown elevates Texas to provincial status in 1728 and begins repopulating the region by settling Canary Islanders (Isleños) in San Antonio by 1731.

Indigenous Alliances, Conflicts, and Diplomacy

The Osage actively ally with the French against the Illiniwek, deepening their diplomatic and trade relationships. French explorer Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont, establishes Fort Orleans in Osage territory, the first European fort on the Missouri River. In a notable diplomatic event in 1725, Bourgmont brings a delegation of Osage leaders to Paris, significantly reinforcing Franco-Osage relations.

In Texas, the establishment of the mission-presidio complex of La Bahía del Espiritu Santo near the San Antonio River in 1722 initially fosters peaceful relations with the Karankawa, though conflict erupts by 1723. By 1727, escalating hostility from the Karankawa compels the Spanish to relocate the complex inland to the Guadalupe River, effectively limiting Spanish influence along the Texas coast.

The Natchez Wars and Indigenous Slave Trade

Continued rivalry between pro-French and pro-English Natchez villages erupts in repeated conflicts known as the Natchez Wars, culminating in the devastating Natchez Rebellion of 1729. French retaliation, supported by the Choctaw, decimates the Natchez, Yazoo, and Koroa tribes. Many survivors flee to join the Chickasaw, while others are captured and sold into slavery by Carolina-based traders. This period highlights the destructive impact of European-induced indigenous conflicts and slave trading.

Key Historical Developments

-

Cheyenne migration into the Black Hills, introduction of horse culture to the Lakota, and subsequent displacement of Kiowa.

-

French colonial expansion along the Mississippi River, establishment of New Orleans as capital, and settlement of German communities on the "German Coast."

-

Spanish reduction of military presence in East Texas and relocation of missions to San Antonio, intensifying conflict with the Lipan Apache.

-

Diplomatic relations between Osage leaders and France, highlighted by their diplomatic mission to Paris in 1725.

-

Natchez Wars leading to significant tribal displacement, slavery, and the reconfiguration of indigenous power dynamics.

Long-Term Consequences and Historical Significance

The era from 1720 to 1731 significantly reshaped the cultural and political landscapes of Gulf and Western North America. Indigenous migrations and intertribal dynamics, driven by European colonization and conflicts, resulted in major territorial and demographic shifts. The expansion of European colonies intensified competition among European powers, reshaping alliances and fueling indigenous conflicts with lasting effects on regional stability and cultural survival.

Gulf and Western North America (1768–1779 CE): Shifting Alliances and Indigenous Adaptations

Indigenous Populations and Epidemics

In the late 1770s, indigenous populations in Texas and surrounding regions face devastating impacts from European-introduced diseases. Notably, the Taovayas, a prominent subgroup of the Wichita people, experience a sharp decline in their power after a smallpox epidemic in 1777 and 1778 kills approximately one-third of their population. The epidemic significantly weakens their strategic influence and alliances in the region.

Realignment of Indigenous Alliances

The once-strong alliance between the Wichita, particularly the Taovayas, and the Comanche begins to deteriorate during this period as the Wichita seek closer relations with Spanish colonial authorities. Meanwhile, the Lipan Apache retreat southward towards the Rio Grande, and the Mescalero Apache move into Coahuila by 1777. The Comanche, whose numbers increase due to abundant buffalo herds, migration from Shoshone groups, and the assimilation of captives from rival tribes, expand their dominance and influence across the southern Plains. Despite their internal division into autonomous bands, the Comanche maintain cultural cohesion, shaping the dynamics of the region profoundly.

Expansion of Horse Culture

By the 1770s, the integration of horse culture has become widespread among the southern Plains tribes, as well as northern groups like the Blackfeet, Gros Ventre, Plains Ojibway, and Plains Cree. The adoption of horses significantly enhances the mobility, hunting capabilities, and intertribal communication among indigenous peoples, fostering the rise of a dynamic "Composite Nation of the Great Plains," characterized by increased trade, social interaction, and occasional conflict.

Spanish Colonization of California

Spanish colonial ambitions extend significantly into Alta California beginning in 1769. In response to perceived threats from Russian and potentially British fur traders exploring the Pacific Northwest, Spanish authorities establish a network of missions, forts (presidios), civilian settlements (pueblos), and ranches (ranchos) along the California coastline. Under orders received by Visitador General José de Gálvez in 1768, the Spanish found critical strategic outposts, such as San Diego and Monterey, "for God and the King of Spain."

By 1776, Alta California becomes part of the newly formed administrative division known as the Commandancy General of the Internal Provinces of the North (Provincias Internas), tasked with invigorating settlement and defending Spanish territorial claims. This period marks the beginning of a sustained effort to assert Spanish sovereignty over California, which will eventually result in the establishment of twenty-one missions along the coastline by 1833.

Key Historical Developments

-

Devastating smallpox epidemic severely weakens the Taovayas and reshapes indigenous alliances in Texas and Oklahoma.

-

Increased dominance and territorial expansion of the Comanche, reshaping the power dynamics across the southern Plains.

-

Widespread adoption of horse culture among Plains tribes, enhancing mobility, trade, and cultural exchanges.

-

Strategic Spanish colonization of Alta California in response to potential competition from Russian and British interests, establishing a lasting mission-presidio-rancho system.

Long-Term Consequences and Historical Significance

The period 1768–1779 signifies a major turning point characterized by shifting alliances, epidemic-induced demographic changes, and intensified Spanish colonial efforts in Gulf and Western North America. The Comanche rise as dominant equestrian warriors and traders, dramatically shaping the cultural and geopolitical landscape. Simultaneously, Spanish colonization of California initiates a period of profound transformation for indigenous societies along the Pacific coast, laying the groundwork for future settlement patterns and regional identities.