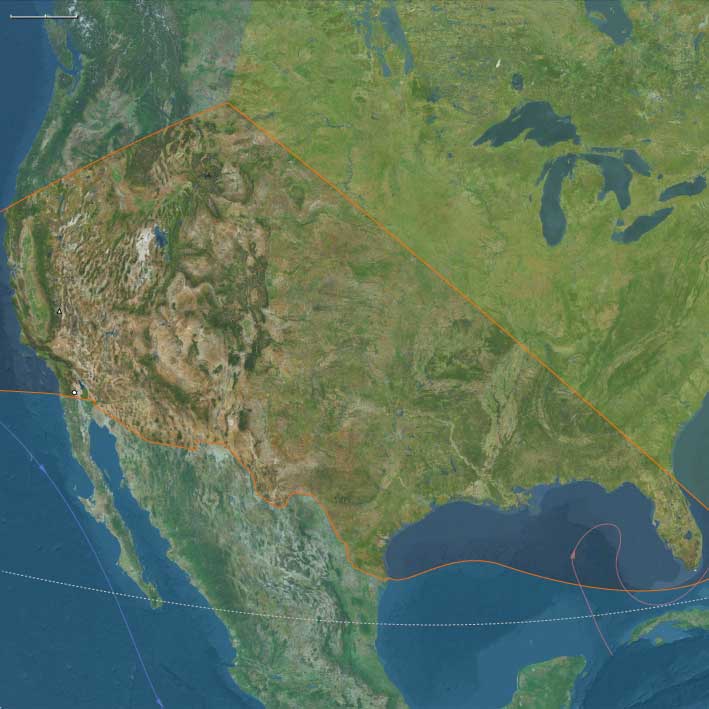

Northern North America (1396–1539 CE) Forests, …

Years: 1396 - 1539

Northern North America (1396–1539 CE)

Forests, Rivers, and the Last Age of Independent Worlds

Geography & Environmental Framework

From the glacier-fed fjords of Alaska and the rainforests of British Columbia to the hardwood valleys of the Great Lakes and the wetlands of the Gulf Coast, Northern North America in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries was a continent of immense ecological variety. The region encompassed the salmon-rich Pacific coasts and interior plateaus, the maize fields and forest clearings of the East, and the arid basins, pueblos, and oak woodlands of the far West.

The Little Ice Age deepened climatic contrasts. Glaciers advanced along the St. Elias and Alaska ranges; sea ice thickened around Greenland and Hudson Bay; drought and flood cycles alternated along the Mississippi, Rio Grande, and Colorado. Storms battered the Atlantic littoral while upwelling currents nourished fisheries on the Pacific. Yet Indigenous societies—adapted to every biome—met these shifts with remarkable resilience, creating a tapestry of ecological adaptation that bound the continent together long before sustained European contact.

Northwestern North America: Coastal Riches and Interior Pathways

Geography & Environmental Context

Stretching from Alaska and the Yukon southward through British Columbia and Washington into northern Oregon, this subregion blended fjorded coastlines, dense cedar forests, salmon-bearing rivers, and sub-Arctic tundra uplands. The Columbia River and the Inside Passage provided natural corridors linking ocean and interior.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

During the early Little Ice Age, glacial tongues advanced in the coastal ranges, and colder seas shortened salmon runs. Intense winter storms alternated with mild decades of recovery. Inland, cooler summers limited wild plant productivity, but trade and storage stabilized food systems.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Coastal nations—Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Nuu-chah-nulth, and Coast Salish—built cedar plankhouses in sheltered bays, fished salmon, halibut, and cod, hunted whales and seals, and gathered berries and roots. The potlatch ceremony redistributed wealth and validated status.

-

Interior and plateau groups—Nez Perce, Carrier, Sekani, Shoshone—followed cyclical routes of fishing, root gathering, and elk and deer hunting, converging at river crossings for trade and ceremony.

-

In the Aleutians, Unangan hunters in semi-subterranean barabaras pursued sea mammals in agile baidarkas.

Technology & Material Culture

Cedar woodworking produced monumental canoes, totem poles, bentwood boxes, and masks that embodied ancestral and animal spirits. Stone adzes, bone fishhooks, and antler harpoons reflected technological mastery. Snowshoes, sledges, and skin clothing extended mobility into icy interiors.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The Inside Passage knit coastal societies into a maritime world of exchange in fish oil, copper, and shell ornaments. The Columbia River linked inland fishing villages to coastal trade, while Aleutian straits connected Alaska with Siberia through small-scale barter networks.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Raven and Thunderbird myths recounted creation and transformation. Totemic carvings displayed clan ancestry; the potlatch dramatized social law and cosmic balance. Shamanic healing and trance rituals bound communities to land, water, and animal spirits.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Communities relied on smoking and drying salmon, storing oil, and seasonal migration between rivers and forests. Trade redistributed surpluses across ecological zones. Ceremony reinforced stewardship, ensuring balance between people and the natural world.

Transition

By 1539 CE, the Pacific Northwest and sub-Arctic were densely peopled, self-governing regions untouched by Europe. Glaciers and seas defined life, and the rhythm of salmon and ceremony shaped civilizations thriving in isolation.

Northeastern North America: Woodland Societies and First Atlantic Glimpses

Geography & Environmental Context

This subregion extended from Florida to Greenland, encompassing the Appalachians, St. Lawrence, Great Lakes, and Hudson Bay. Temperate forests merged with boreal shield and tundra, forming one of the most ecologically varied landscapes on Earth.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Little Ice Age brought long winters and shortened growing seasons. Snowpack lingered on uplands; Atlantic storms reshaped barrier coasts; northern ice thickened across Greenland and Labrador. Despite harsher conditions, forest and aquatic productivity supported dense and enduring populations.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Iroquoian and Algonquian farmers cultivated maize, beans, and squash in fertile river valleys, supplementing with hunting and fishing. Longhouse villages and fortified palisades dotted the Finger Lakes and St. Lawrencevalleys.

-

Great Lakes peoples managed fisheries and engaged in extensive copper and shell trade.

-

Canadian Shield hunters followed caribou, moose, and fish, practicing seasonal mobility.

-

Inuit Thule communities in Greenland and Labrador expanded dog-sled and umiak travel, perfecting seal and whale hunting.

-

Bermuda remained uninhabited, a sanctuary for seabirds and turtles.

Technology & Material Culture

Birchbark canoes, dugouts, snowshoes, bows, and polished stone tools enabled adaptation to forest and river. Wampum belts recorded treaties and myth; pottery, textiles, and copper ornaments expressed artistry. Inuit toggling harpoons, bone goggles, and tailored skins exemplified Arctic ingenuity.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Canoe routes along the St. Lawrence, Great Lakes, and Mississippi bound distant polities in trade and diplomacy. Coastal peoples navigated estuaries for fishing and exchange. Inuit crossed sea-ice to Baffin Island and Labrador, maintaining circumpolar networks.

By the early sixteenth century, Portuguese, Basque, and Breton fishers anchored off Newfoundland, harvesting cod and whale oil—fleeting contact without conquest.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Woodland cosmologies envisioned spirits in animals, rivers, and maize. Shamans mediated between visible and invisible realms; ceremonies of planting, hunting, and mourning affirmed communal balance. Wampum diplomacy symbolized alliances, while Inuit storytelling, drumming, and carving honored sea spirits and ancestors.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Intercropped maize fields, stored surpluses, and hunting cycles buffered scarcity. Wild rice and maple sugar enriched northern diets. Inuit adapted to extreme cold through fuel-efficient dwellings and clothing design. Cooperation ensured survival through climatic volatility.

Transition

By 1539 CE, northeastern societies remained autonomous. Europe’s presence was limited to cod fleets and mapmakers. The vast woodlands, lakes, and tundra still belonged to their Indigenous custodians.

Groups

- Kwakwakaʼwakw

- Haida people

- Tlingit people

- Athabaskans, or Dene, peoples

- Klamath (Amerind tribe)

- Nuu-chah-nulth people (Amerind tribe; also formerly referred to as the Nootka, Nutka, Aht, Nuuchahnulth)

- Tsimshian

- Eyak

- Aleutian Tradition

- Thule Tradition, Punuk and Birnirk Stages

Commodoties

Subjects

- Commerce

- Watercraft

- Sculpture

- Painting and Drawing

- Environment

- Decorative arts

- Mayhem

- Government

- Custom and Law

- Technology