Northern North America (820 – 963 CE): …

Years: 820 - 963

Northern North America (820 – 963 CE): Salmon Worlds, Woodland Mosaics, and Mound Horizons

Geographic and Environmental Context

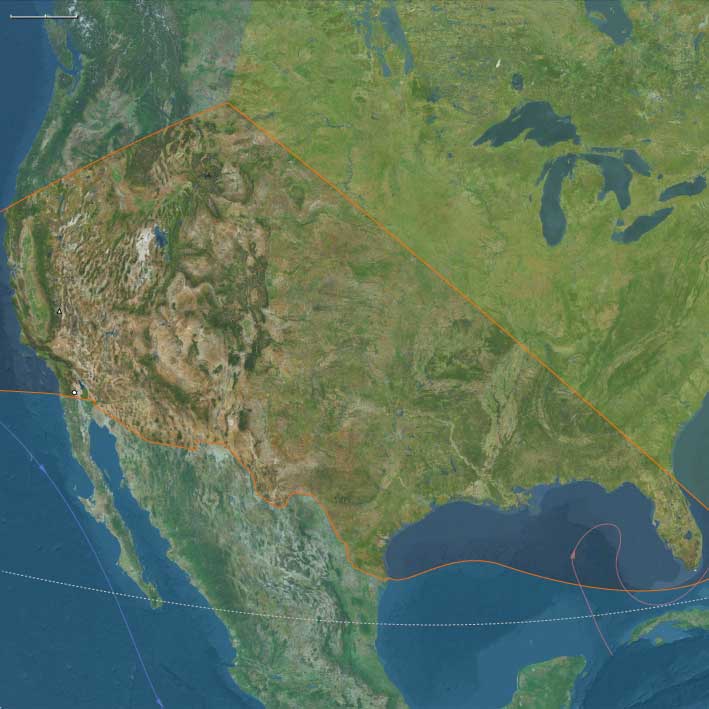

Northern North America stretched from the Pacific fjords and salmon rivers of Alaska and British Columbia to the Great Lakes and Mississippi valleys, the Appalachian woodlands, and the Gulf–Southwest deserts and plains.

-

Northwest: temperate rainforests and fjord coasts of the Pacific, merging with subarctic taiga and Arctic tundra.

-

Northeast: broad river valleys, Great Lakes basins, Atlantic seaboard, and Greenland’s fjordlands.

-

Gulf & West: the Mississippi and Arkansas basins, desert Southwest, and California’s coasts and oak savannas.

These varied landscapes sustained distinct yet interconnected economies of salmon, maize, and mound-building and sea-mammal hunting, all adapting to warming conditions as the Medieval Warm Period began around 950 CE.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

Pacific coast: cool, wet regimes fostered vast cedar and hemlock forests; longer summers enhanced salmon productivity.

-

Interior plains and woodlands: warmer, wetter centuries advanced maize cultivation into the Ohio–Mississippi valleys.

-

Arctic and subarctic: seasonal sea-ice retreat improved marine hunting; inland caribou and moose herds expanded.

-

Southwest: stable precipitation favored canal irrigation; California’s Mediterranean rhythm supported oak and marine abundance.

These conditions encouraged population growth, sedentism, and regional integration.

Societies and Political Developments

Northwestern North America

-

Coastal chiefdoms—Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Kwakwakaʼwakw, Coast Salish—organized into ranked lineages that controlled fisheries and ceremonial exchange (potlatch).

-

Unangan, Sugpiaq, Yup’ik–Inupiat mastered sea-mammal hunting from the Aleutians to the Arctic.

-

Athabaskan (Dene) bands coordinated caribou hunts and riverine fisheries inland.

-

Villages of cedar plank-houses and monumental art expressed hereditary prestige; inland, leadership was merit-based and mobile.

Northeastern North America

-

Woodland cultures (Iroquoian, Algonquian ancestors) practiced mixed farming, hunting, and fishing from the Appalachians to the Great Lakes.

-

Mississippian precursors in the Ohio–Illinois valleys organized maize-based mound centers.

-

Prairie societies blended bison hunting with riverine farming.

-

Greenland Norse colonies formed late in this age (~985), linking the North Atlantic to European trade.

-

Arctic Dorset peoples persisted before later Thule migrations.

Gulf and Western North America

-

Lower Mississippi communities raised platform mounds at Plaquemine and Caddoan sites.

-

Chaco Canyon (850–1130) blossomed with great houses, roads, and regional integration.

-

Hohokam irrigators along the Salt–Gila rivers cultivated maize, beans, and cotton.

-

Mogollon and Sinagua villagers farmed uplands; Chumash chiefdoms expanded their tomol canoe trade between the Channel Islands and mainland California.

-

The Great Basin remained home to highly mobile foragers trading salt and obsidian.

Economy and Trade

-

Coastal salmon economies: smoked and dried fish sustained dense settlements; eulachon oil circulated as prestige wealth.

-

Fur, copper, and dentalium moved along interior–coastal trade paths linking Dene hunters and Northwest Coast carvers.

-

Maize, beans, and squash supported mound-center surpluses; shell beads, mica, and copper traveled the Mississippi corridor.

-

Southwest networks carried turquoise, macaws, and copper bells from Mesoamerica to Chaco; Hohokam exported cotton and shell jewelry.

-

California distributed shell currency north and obsidian east; the Great Basin mediated salt and desert goods.

-

Atlantic and Great Lakes trade moved copper, wampum-like ornaments, and marine shells over thousands of kilometers.

-

Greenland exported walrus ivory and hides to Europe at the period’s close.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Cedar architecture and canoes defined the Pacific coast; interior pit-houses and bark lodges housed Dene and Plateau peoples.

-

Weirs, reef-nets, and wicker traps optimized salmon harvests; smokehouses and grease rendering secured surplus.

-

Canal irrigation and terraced fields underpinned Hohokam and Chaco agriculture.

-

Mound construction required coordinated labor and stored maize.

-

Tomol plank canoes of the Chumash and skin-boats of the Arctic extended seafaring economies.

-

Iron was unknown, but native copper, bone, stone, and wood technologies were highly refined.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Northwest Coast cosmologies dramatized animal ancestors—Raven, Eagle, Wolf, Killer Whale—through masks, poles, and potlatch rites.

-

Woodland mound cosmologies aligned earth, sky, and underworld in their architecture.

-

Chaco’s kivas embodied solar and cardinal symbolism; astronomy regulated ritual calendars.

-

California and Arctic shamans mediated between people and animal spirits; carved regalia and rock art memorialized transformation myths.

-

Greenland Norse practiced pagan burial customs soon to yield to Christianity.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Multi-resource economies—salmon, maize, acorns, sea-mammals, and game—buffered environmental risk.

-

Preservation technologies (drying, smoking, rendering oils) stabilized food supplies.

-

Trade alliances and kin networks distributed surpluses and mitigated famine.

-

Mobility: canoes, sleds, and foot trails ensured resource flexibility across ecological zones.

-

Ritual redistribution (potlatch, feasts) converted surplus into prestige and diplomacy.

Long-Term Significance

By 963 CE, Northern North America had matured into a tapestry of salmon chiefdoms, woodland farmers, and desert irrigators connected by trade and shared ecological intelligence:

-

Northwest Coast chiefdoms exemplified surplus-based artistry and ranked social orders.

-

Woodland and Mississippian peoples advanced maize agriculture and mound ceremonialism.

-

Chaco and Hohokam anchored southwestern urbanization, while Chumash maritime trade linked the Pacific rim.

-

Across the continent, Dene and Inuit mobility, Atlantic mound-building, and Greenland colonization prefigured the continental complexity of later centuries.

These interwoven economies of salmon, maize, and monumental exchange formed the ecological and cultural foundations for the flourishing civilizations of medieval and early modern North America.

Groups

- Kwakwakaʼwakw

- Coast Salish

- Haida people

- Tlingit people

- Athabaskans, or Dene, peoples

- Nuu-chah-nulth people (Amerind tribe; also formerly referred to as the Nootka, Nutka, Aht, Nuuchahnulth)

- Tsimshian

- Aleut people

- Alutiiq (Eskimo tribe)

- Inupiat

- Inuit

- Gwichʼin

- Kaska Dena

- Dakelh

- Tahltan

- Yupʼik

Topics

Commodoties

Subjects

- Commerce

- Architecture

- Watercraft

- Sculpture

- Environment

- Decorative arts

- Mayhem

- Faith

- Government

- Custom and Law

- Technology