Northern Macaronesia (1396–1539 CE): Discovery, Colonization, and …

Years: 1396 - 1539

Northern Macaronesia (1396–1539 CE): Discovery, Colonization, and Atlantic Integration

Geographic & Environmental Context

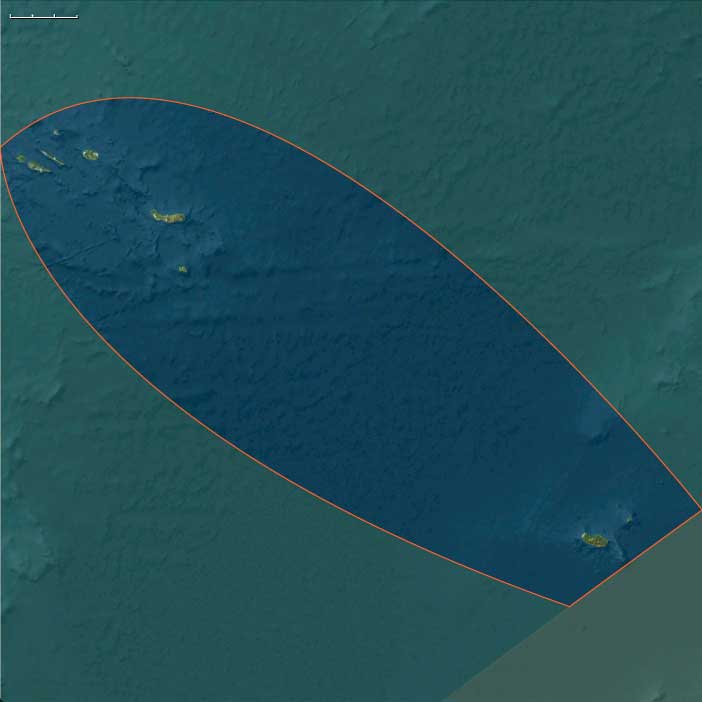

The subregion of Northern Macaronesia includes the Azores and Madeira archipelago. The Azores stretched in three groups of volcanic islands (western, central, eastern) across the mid-Atlantic, with high peaks, calderas, and crater lakes. Madeira featured rugged volcanic massifs, deep valleys, and laurel-clad uplands. Both archipelagos were positioned in the North Atlantic subtropical gyre, at the crossroads of winds and currents that soon became indispensable to Iberian navigation.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

During this age, the early centuries of the Little Ice Age brought cooler winters and occasional drought in the Azores, but the maritime climate moderated extremes. Madeira’s laurel forests continued to harvest cloud moisture, while leeward coasts grew drier. Seasonal storms occasionally battered harbors, yet fertile volcanic soils sustained productive agriculture.

Subsistence & Settlement

This was the pivotal era of human arrival and colonization:

-

Madeira: Discovered by Portuguese navigators c. 1419. Settlement soon followed, clearing laurel forests for wheat, vineyards, and especially sugarcane, cultivated with enslaved labor (African and later Guanche captives).

-

Azores: Officially discovered c. 1427, settled by Portuguese colonists, including Flemings and other Europeans. Agriculture centered on wheat, vineyards, orchards, and livestock. Fishing and whaling developed offshore.

-

Indigenous populations did not exist in these northern archipelagos; settlement began directly with colonization.

Technology & Material Culture

Portuguese colonists introduced iron tools, plows, sugar mills, waterwheels, and terracing techniques. Stone churches, forts, and towns (e.g., Funchal in Madeira, Angra in the Azores) embodied European architectural traditions. Sugar production technology integrated Iberian, Mediterranean, and Islamic precedents. Material culture included ceramics, textiles, and hybrid Afro-Portuguese religious and artistic forms brought by enslaved laborers.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Northern Macaronesia became a keystone in Atlantic navigation:

-

The Azores lay on the return route for Iberian fleets from Africa and the Americas, serving as staging posts and weathering ports.

-

Madeira exported sugar and wine to Europe, linking the islands into Mediterranean and northern European markets.

-

Both archipelagos became hubs in the transatlantic system, receiving enslaved Africans and exporting cash crops.

These corridors made the islands both economic engines and geopolitical prizes.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Catholicism was established immediately with colonization. Churches, chapels, and processions anchored religious life. Marian devotion in Madeira and the cult of the Holy Spirit in the Azores became central symbolic expressions, blending Iberian Christianity with the lived reality of frontier life. Music, oral traditions, and festivals reflected Portuguese heritage, with African influences emerging subtly in labor and ritual.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Colonists reshaped fragile island ecologies:

-

Deforestation of Madeira’s laurisilva destabilized slopes and altered watersheds.

-

Terracing and irrigation adapted to steep volcanic terrain.

-

In the Azores, cattle ranching, grain fields, and vineyards were adapted to wetter conditions and storm exposure.

Resilience was found in diversified crops, shared labor systems, and integration into wider imperial trade, though ecological degradation had already begun.

Transition

By 1539 CE, Northern Macaronesia was firmly integrated into the Portuguese Atlantic empire. Madeira was a major sugar producer, the Azores a critical provisioning and navigation hub. Both archipelagos were transformed from pristine oceanic ecosystems into human-dominated plantation and trade landscapes, foreshadowing the role of Atlantic islands as laboratories of colonization and models for the Americas.