South America (1540 – 1683 CE) …

Years: 1540 - 1683

South America (1540 – 1683 CE)

Empires of Silver and Sugar, Frontiers of Resistance

Geographic Definition of South America

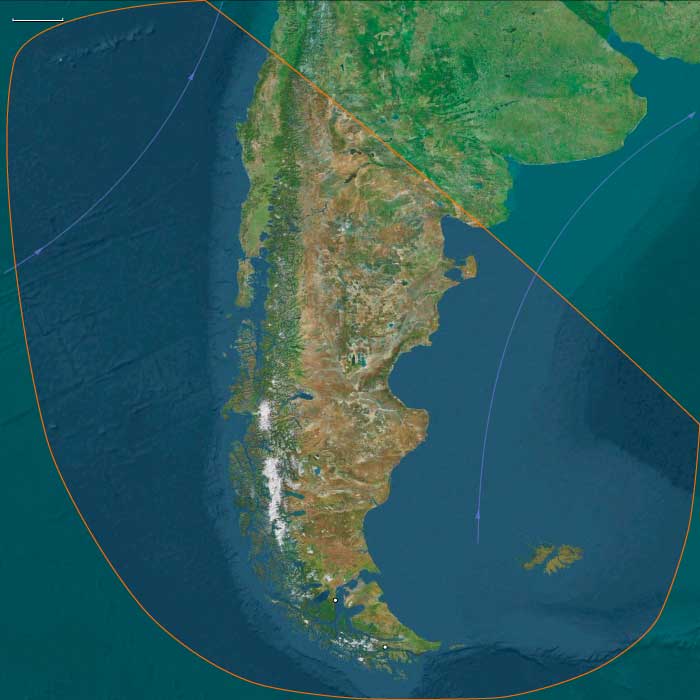

The region of South America includes all lands south of the Isthmus of Panama: Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, northern Argentina and northern Chile, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador (excluding the Cape lands), Colombia (excluding the Darién region), Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana, and, farther south, southern Chile, southern Argentina, Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego, the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas), and the Juan Fernández Islands.

Anchors spanned the Andes cordillera and Altiplano, the Amazon, Orinoco, and Magdalena river systems, the Venezuelan Llanos, Gran Chaco, Pampas, and Guiana Shield, extending south to the Araucanian Andes, the Patagonian steppe, and the Strait of Magellan.

From rainforest to desert, from ice-bound fjords to equatorial coasts, the continent entered its first great age under Iberian rule—an age of extractive empires, enslaved labor, and enduring Indigenous worlds beyond the reach of crown and cross.

Imperial Geography and Environmental Frontiers

By the mid-sixteenth century, two colonial powers divided the continent:

Spain, governing through the Viceroyalty of Peru (established 1542), ruled from Lima across the Andes to the silver mines of Potosí and the highland cities of Cuzco, Quito, and La Paz;

Portugal, through the State of Brazil (from 1549), commanded the Atlantic rim from Bahia and Pernambuco to Rio de Janeiro.

Between them stretched immense interior worlds—Amazonian forests, Chaco plains, Llanos, and southern pampas—where Indigenous confederations, runaway slaves, and missionary enclaves coexisted beyond direct imperial reach.

Farther south, Mapuche, Tehuelche, and Fuegian nations held their territories against repeated incursions, making the sub-Antarctic fringe the last unconquered frontier of Iberian America.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The Little Ice Age defined the era’s physical rhythm.

-

Andes and Altiplano: Cooler temperatures and erratic frosts shortened harvests; El Niño floods devastated Peruvian coasts and fisheries.

-

Amazon and Orinoco: Alternating decades of deluge and drought altered navigation and field cycles.

-

Gran Chaco and Pampas: Droughts followed by torrential rains tested herders and farmers.

-

Southern Chile and Patagonia: Harsher winters and advancing glaciers limited crops but preserved pastoral abundance.

Despite climatic volatility, Indigenous and colonial systems adapted—terracing, irrigation, and crop rotation in the highlands; shifting cultivation and fisheries in the lowlands; and new livestock economies across the southern plains.

Subsistence and Settlement

Colonial and Indigenous societies intertwined yet remained distinct.

-

Andean Highlands: Spaniards imposed encomienda and mita labor drafts; Indigenous farmers sustained maize, potato, and quinoa cycles; and Potosí’s silver—extracted by Aymara and Quechua labor—underwrote imperial finance.

-

Pacific Coasts: Sugar, cotton, and vineyards flourished on coastal haciendas worked by enslaved Africans and Indigenous tenants.

-

Brazilian Coast: Sugar plantations in Bahia and Pernambuco dominated exports; African slavery expanded while Jesuit missions sought (and often failed) to protect Indigenous captives.

-

Southern Brazil and Paraguay: Cattle ranching spread over grasslands, creating the first gaucho frontiers; Jesuit reducciones organized Guaraní communities around churches, workshops, and communal fields.

-

Amazon and Guianas: Arawak, Tupí, and Carib societies persisted through horticulture, fishing, and flight from slavers; European forts and missions remained precarious outposts.

-

Southern Chile and Patagonia: The Mapuche maintained farming and trade south of the Bio-Bío; Tehuelche hunters roamed the steppe; Yaghan, Kawésqar, and Selk’nam peoples sustained maritime and inland lifeways untouched by permanent colonies.

Urban grids from Lima and Quito to Salvador and Santiago reflected imperial order, while vast hinterlands preserved pre-colonial autonomy.

Technology and Material Culture

Iberian technologies fused with Indigenous and African ingenuity:

-

Mining & metallurgy: Mercury amalgamation, mule-driven mills, and deep shafts redefined Andean landscapes.

-

Agriculture & transport: European plows, oxen, and terraces merged with Inca irrigation and storage systems.

-

Architecture: Rectilinear plazas, adobe houses, and stone churches rose through Indigenous labor; the Cusco School and Guaraní baroque sculpture merged local motifs with Christian iconography.

-

Lowland and frontier crafts: Dugout canoes, feather ornaments, and maroon ironwork embodied resistance and adaptation.

-

Southern frontier: The Mapuche’s adoption of the horse and iron weapons created a formidable cavalry culture that stalemated Spanish expansion for generations.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

South America’s circulation systems bound highlands, coasts, and oceans into a global network:

-

Qhapaq Ñan: The Inca road network became the backbone of colonial transport linking Lima, Potosí, and Quito.

-

Pacific & Atlantic routes: Silver, sugar, and hides moved through Callao, Cartagena, and Bahia to Seville and Lisbon.

-

Slave and mission networks: African captives entered via Cartagena, Salvador, and Lima; Jesuit and Franciscan missions spanned Paraguay, Bolivia, Amazonia, and Venezuela.

-

Indigenous & maroon corridors: Canoe and foot trails connected autonomous villages across the Amazon and Chaco, carrying goods, stories, and fugitives beyond imperial control.

-

Southern seas: The Strait of Magellan and Juan Fernández Islands became vital provisioning points for galleons and privateers.

Cultural and Symbolic Expressions

Catholic orthodoxy framed the public sphere, but syncretic traditions flourished beneath it.

-

Andes: Veneration of the Virgin intertwined with mountain deities (apus) and Pachamama; feast days mirrored ancient agricultural rituals.

-

Brazil & Guianas: Enslaved Africans and Indigenous peoples created hybrid faiths blending saints with orixás, drumming with procession.

-

Guaraní missions: Choirs sang polyphonic hymns in Indigenous languages; carved angels bore Guaraní faces.

-

Mapuche and Tehuelche southlands: Ritual feasts (ngillatun) and ancestral songs affirmed identity against foreign power.

-

Art & music: Andean painting schools, Jesuit orchestras, and African percussion enriched a continental baroque unlike any in Europe.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Survival rested on ecological knowledge:

-

Highlands: Terraces, communal granaries, and mixed cropping cushioned climatic shocks.

-

Lowlands: Rotational gardens and foraging sustained food security; flight into forest refuges preserved freedom.

-

Missions: Combined maize, manioc, and European grains in sustainable polycultures.

-

Southern frontier: Mobility and cavalry warfare enabled Mapuche and Tehuelche resilience; canoe peoples of Tierra del Fuego maintained fire-lit cooperation in icy seas.

These strategies—diversified crops, mobile herds, and ritual reciprocity—ensured endurance across conquest and climate alike.

Technology and Power Shifts (Conflict Dynamics)

Imperial control expanded but never absolute:

-

Spanish consolidation: The Viceroyalty of Peru centralized administration; governors and clergy extended rule through coercion and conversion.

-

Portuguese assertion: The Governorate General of Brazil established Salvador as capital and fortified the coast, while bandeirantes pressed westward for slaves and gold.

-

Indigenous uprisings: From the Neo-Inca state at Vilcabamba (1537–1572) to Mapuche wars in Chile and Tupinambá revolts in Brazil, resistance persisted.

-

African maroons: Quilombos such as Palmares in northeast Brazil formed autonomous states blending African, Indigenous, and European traditions.

-

Imperial rivalry: Dutch and French privateers attacked Pernambuco and Maranhão; English corsairs raided the Pacific; Spanish–Portuguese boundaries blurred across the interior.

By the late seventeenth century, Iberian empires held the coasts and mines, but the heart of the continent—Amazon, Chaco, Patagonia—remained beyond their grasp.

Transition (to 1684 CE)

By 1683 CE, South America was both imperial citadel and frontier wilderness.

The Andes poured silver to Europe; Brazil’s plantations sustained the Atlantic economy. Jesuit missions, fortified cities, and royal roads proclaimed dominion—yet Indigenous nations, African maroons, and remote settlers governed vast interiors in their own ways.

From Potosí’s frozen summits to Bahia’s humid mills, from Lima’s plazas to Araucanía’s palisades, the continent bore the dual imprint of empire and resistance.

It entered the next age as a world of bound empires and unbroken peoples—its wealth feeding distant crowns, its endurance rooted in landscapes and cultures that empire could reshape but never erase.

Groups

- Mapuche (Amerind tribe)

- Portuguese people

- Guaraní (Amerind tribe)

- Christians, Roman Catholic

- Portugal, Avizan (Joannine) Kingdom of

- Portuguese Empire

- Spanish Empire

- Brazil, Colonial

- Spaniards (Latins)

- Spain, Habsburg Kingdom of

- Jesuits, or Order of the Society of Jesus

- Charcas, Real Audiencia of (Upper Peru)

- Spain, Habsburg Kingdom of

- Quito, Real Audiencia of

- Bogotá, Audiencia de Santa Fe de (Captaincy General of New Granada)

Topics

- Age of Discovery

- Colonization of the Americas, Portuguese

- Colonization of the Americas, Spanish

- Columbian Exchange