South Polynesia (1252 – 1395 CE): …

Years: 1252 - 1395

South Polynesia (1252 – 1395 CE):

Aotearoa’s Settlement, Chatham Isolation, and Expanding Canoe Chiefdoms

Geographic and Environmental Context

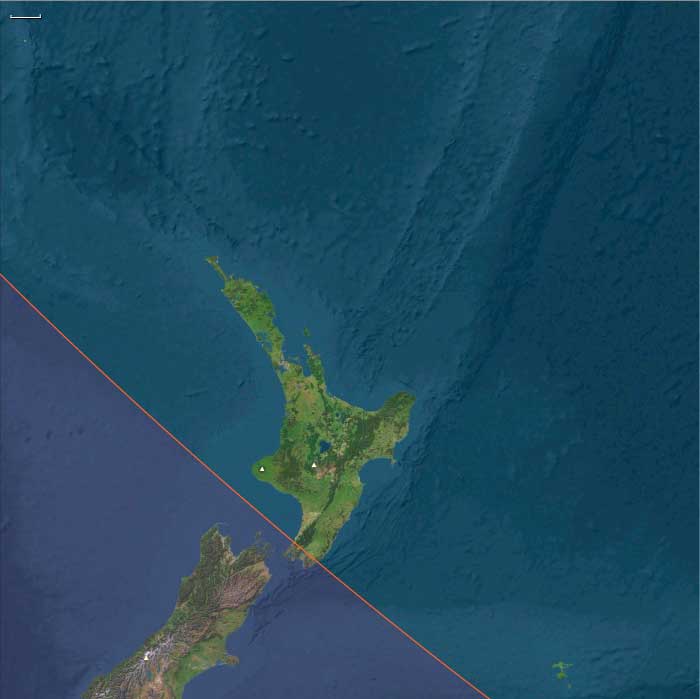

South Polynesia includes New Zealand’s North Island (except its southern coast), the Chatham Islands, Norfolk Island, and the Kermadec Islands—a temperate extension of the wider Polynesian world.

-

North Island (Aotearoa): volcanic uplands, fertile alluvial valleys, temperate forests, and extensive coasts with rich fisheries.

-

Chatham Islands: cooler, wind-swept, with limited forest and agriculture; communities relied on marine and seabird resources.

-

Norfolk and Kermadec Islands: small volcanic isles with fertile soils and fringing reefs, maintaining modest Polynesian horticultural economies.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The transition into the early Little Ice Age (after c. 1300 CE) brought cooler, wetter conditions in New Zealand.

-

Shorter growing seasons challenged tropical cultigens (taro, yam, breadfruit), encouraging diversification toward kūmara (sweet potato), fern root, and bracken gardens.

-

On the Chathams, cooler conditions limited gardening, favoring fishing, birding, and sealing.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Aotearoa (North Island):

East Polynesian settlers arrived c. 1200–1300 CE. By the mid-14th century, sizeable iwi (tribes) and hapū (sub-tribes) had formed. Canoe traditions (Arawa, Tainui, Mataatua, etc.) provided genealogical legitimacy and territorial identity. Settlement patterns combined fortified pā (hill forts) with dispersed horticultural hamlets. -

Chatham Islands:

Settlers diverged culturally into the Moriori, adapting to limited gardening by emphasizing fishing, sealing, and seabird harvests. Egalitarian councils replaced hierarchical Polynesian chiefly systems. -

Norfolk and Kermadec Islands:

Sparse settlements maintained Polynesian horticulture and fishing lifeways, linked by periodic canoe voyages to Aotearoa.

Economy and Trade

-

Aotearoa: Kūmara cultivation in northern valleys; smaller plots of taro, yam, and gourds where viable. Supplementary staples included fern-root, cabbage-tree root, and berries. Protein came from moa (declining by late 14th century), seals, fish, shellfish, and forest birds.

-

Chathams: Marine-centered economy of seals, seabirds, fish, and shellfish; only limited kūmara attempts.

-

Norfolk and Kermadecs: Mixed horticulture (taro, yams, kūmara), coconuts, and reef fishing.

-

Exchange: Canoe voyages connected offshore isles to Aotearoa’s coasts; greywacke and obsidian tools, feathers, and ritual valuables circulated.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Agriculture: Kūmara grown in storage pits and ridged fields; fern-root gardens on upland slopes.

-

Hunting & fishing: Large nets, hooks, traps, and bird snares; moa and seal hunts central in early settlement.

-

Architecture: Whare (timber-reed houses) and pā fortifications with ditches and palisades.

-

Canoes: Double-hulled voyaging canoes for inter-island travel; river and coastal craft for fishing and trade.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Canoe networks tied iwi settlements across Aotearoa, maintaining marriage and exchange ties.

Norfolk and Kermadec routes conveyed horticultural cultigens and stone tools.

The Chathams, after initial contact, grew increasingly isolated, developing distinctive lifeways.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Aotearoa Māori:

Cosmology centered on atua (deities), descent from canoe ancestors, and ritual specialists (tohunga). Tapu and mana structured land, leadership, and resource use. -

Moriori (Chathams):

Emphasized peace-making and collective governance, adapting rituals to marine environments. -

Sacred landscapes: Mountains, rivers, and forests remained infused with the presence of atua and canoe-ancestor narratives.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Aotearoa: Diversified food base—kūmara, fern-root, hunting, and fishing—buffered cooler conditions.

-

Chathams: Marine specialization ensured survival where crops failed.

-

Offshore islands: Maintained resilience through small-scale horticulture and exchange with Aotearoa.

-

Pā fortifications and inter-tribal alliances mitigated conflict and resource stress.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395 CE, South Polynesia had become a frontier of Polynesian adaptation:

-

Aotearoa Māori consolidated iwi and hapū identities around canoe genealogies, horticulture, and fortified settlements.

-

Moriori on the Chathams embodied a divergent, egalitarian, marine-adapted culture.

-

Norfolk and Kermadecs remained small but vital outposts linking South Polynesia to wider voyaging routes.

These transformations marked Polynesia’s bold expansion into temperate and subpolar zones—reshaping lifeways far from tropical origins.