Australasia (1252–1395 CE): Southern Voyages, Temperate Adaptations, …

Years: 1252 - 1395

Australasia (1252–1395 CE): Southern Voyages, Temperate Adaptations, and Law of the Land

Geographic and Environmental Framework

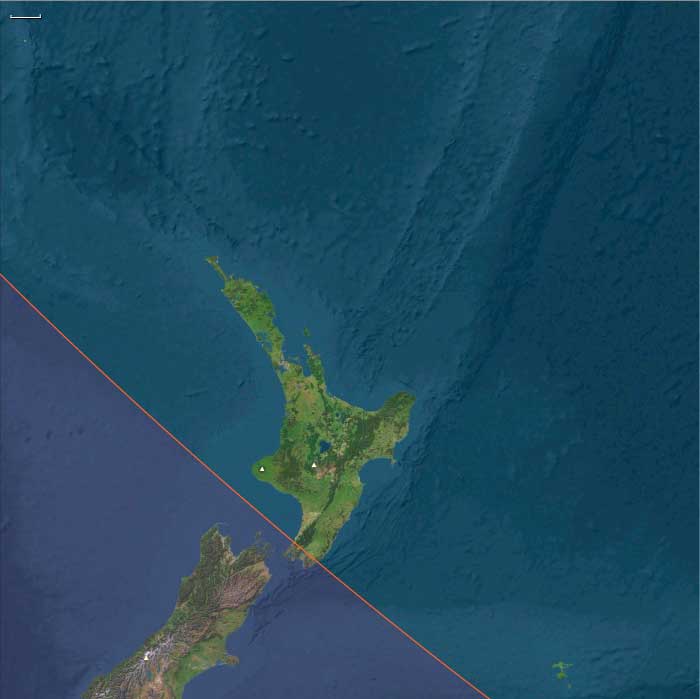

Australasia in the Lower Late Medieval Age spanned a vast temperate and tropical continuum—from the voyaging frontiers of South Polynesia to the fertile river basins of Southern Australia and the monsoon-driven coasts of Northern Australia.

The region’s islands and continents formed an intricate mosaic of ecosystems and lifeways:

-

Aotearoa (New Zealand) and its outlying islands (Chatham, Norfolk, Kermadec) stood at the cool, temperate edge of Polynesia, where new settlers adapted tropical horticulture to shorter growing seasons.

-

Southern Australia and Tasmania preserved long-established Aboriginal foraging systems rooted in ritual law and fire-managed landscapes.

-

Northern Australia and the Torres Strait Islands connected the Australian mainland to New Guinea, blending monsoon foraging, wetland hunting, and horticultural–maritime chiefdoms.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The onset of the Little Ice Age after c. 1300 CE brought cooler, wetter climates to the southern temperate zones and slightly drier variability to the north.

-

New Zealand: Shortened growing seasons and periodic frosts challenged taro and yam cultivation, prompting reliance on kūmara (sweet potato), fern root, and bracken.

-

Southern Australia and Tasmania: Temperature declines were modest; flexible fire-based foraging adjusted easily.

-

Northern Australia: Monsoon variability increased, but wetlands and reefs remained highly productive.

Across the region, communities responded with diversified subsistence, intensified exchange, and ceremonial frameworks that redistributed risk.

Societies and Political Developments

Aotearoa and the Southern Islands

East Polynesian voyagers reached Aotearoa around 1200–1300 CE, establishing dispersed horticultural hamlets and fortified pā. By the mid-14th century, sizeable iwi (tribes) and hapū (sub-tribes) emerged, anchored in canoe genealogies (Arawa, Tainui, Mataatua) that legitimized land and lineage.

On the Chatham Islands, settlers evolved into the Moriori, adapting to cooler climates with marine specialization and egalitarian governance.

Norfolk and Kermadec Islands remained small but vital outposts linked to Aotearoa through ritual and exchange.

Southern Australasia

In New Zealand’s South Island, Māori expansion created mixed economies: horticulture in northern valleys, hunting of moa, seals, and eels in southern zones—early expressions of Ngāi Tahu identity.

Across southern Australia and Tasmania, Aboriginal and Palawa societies maintained flexible kin-based networks, practicing firestick farming, riverine fishing, and seasonal migration between coasts, rivers, and uplands.

Large ceremonial gatherings along the Murray–Darling Basin reinforced intergroup alliances through exchange of ochre, greenstone, and ritual performances.

Northern Australia and the Torres Strait

In Arnhem Land and the Kimberley, clan societies ordered by the Dreaming maintained songline networks linking land, sky, and sea.

Cape York and Gulf populations held wet-season festivals and dry-season hunts, integrating multiple language groups.

Across the Torres Strait Islands, horticultural–maritime chiefdoms flourished—growing taro, yams, and bananas; cultivating reef fisheries; and trading with both Papua and Australia. Hereditary leaders (mamoose) presided over complex initiation and fertility rites.

Economy, Exchange, and Technology

Horticultural and Foraging Systems

-

Māori horticulture: Kūmara grown in storage pits and ridged fields; taro, yam, and gourds cultivated where possible.

-

Aboriginal Australia: Root crops, marsupials, and fish taken from managed landscapes shaped by controlled burning.

-

Tasmania: Littoral hunting and inland foraging for shellfish, seals, wallabies, and tubers.

-

Torres Strait: Mixed horticulture of taro, yam, banana, and sugarcane integrated with turtle and dugong fishing.

Trade and Interaction Networks

-

Polynesian linkages: Canoe routes connected Aotearoa with Norfolk and Kermadec Islands; stone tools and feathers exchanged among iwi.

-

Trans-Tasman circuits: Pounamu (greenstone) moved across New Zealand’s South Island; ochre and axes circulated across mainland Australia.

-

Torres Strait hub: The crucial conduit between New Guinea and Australia, transferring pearl shell, turtle shell, dugong tusks, canoes, and ceremonial goods.

-

Songlines and rivers: Functioned as spiritual and logistical corridors across the continent, binding far-flung societies through narrative geography.

Technology and Material Culture

-

Canoes: Double-hulled voyaging vessels in Aotearoa; large outrigger sailing craft in the Torres Strait; bark and dugout canoes for fishing across Australia.

-

Architecture: Māori whare and fortified pā; Aboriginal bark shelters and eel-trap villages; Torres Strait men’s houses for ceremony and governance.

-

Tools: Stone adzes, obsidian flakes, shell scrapers, wooden clubs, nets, and drums; artistry expressed in carving, feather ornamentation, and rock art.

Belief, Symbolism, and Law

Across Australasia, cosmology integrated environment, ancestry, and moral order.

-

Māori cosmology: Atua (deities) and canoe ancestors governed land tenure, warfare, and ritual. Tapu and manadefined sacred authority, mediated by tohunga.

-

Moriori belief: Peace-making and collective decision-making replaced hierarchical ritual, reflecting adaptation to isolation.

-

Aboriginal and Palawa Dreaming: Totemic ancestors shaped every landscape; song, dance, and art re-enacted their creation.

-

Torres Strait spirituality: Ancestral spirits of sea and sky embodied in masks and initiation cults; ceremonies linked warfare, fertility, and navigation.

Spiritual systems bound society to ecology—affirming stewardship through sacred law rather than centralized states.

Adaptation and Resilience

The peoples of Australasia met climatic and ecological challenges with ingenuity:

-

Māori diversified crops and fortified pā for defense amid resource pressure.

-

Moriori and island settlers emphasized maritime economies and cooperation.

-

Aboriginal Australians sustained mobility, fire management, and ritual governance to maintain balance.

-

Torres Strait Islanders combined horticulture and navigation, sustaining trade and diplomacy across seas.

Each community integrated environmental knowledge, ritual reciprocity, and flexible subsistence to ensure continuity through cooler centuries.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395 CE, Australasia had crystallized as a realm of parallel adaptation and enduring diversity:

-

Māori societies forged resilient iwi/hapū polities—fortified, horticultural, and ocean-connected.

-

Moriori demonstrated peaceful, marine-adapted lifeways born of isolation.

-

Aboriginal Australians and Palawa peoples maintained ancient Dreaming economies rooted in mobility and ecological law.

-

Torres Strait Islanders stood as cultural intermediaries between New Guinea and Australia, blending trade, ceremony, and cultivation.

Together, these societies defined Australasia as the meeting ground of voyagers and foragers, where tropical seafaring traditions met continental law, and where adaptation to climate, geography, and spirit produced one of humanity’s most enduring tapestries of ecological and cultural resilience.