Southeast Indian Ocean (6,093 – 4,366 BCE): …

Years: 6093BCE - 4366BCE

Southeast Indian Ocean (6,093 – 4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Deglaciated Valleys and Expanding Rookeries

Geographic & Environmental Context

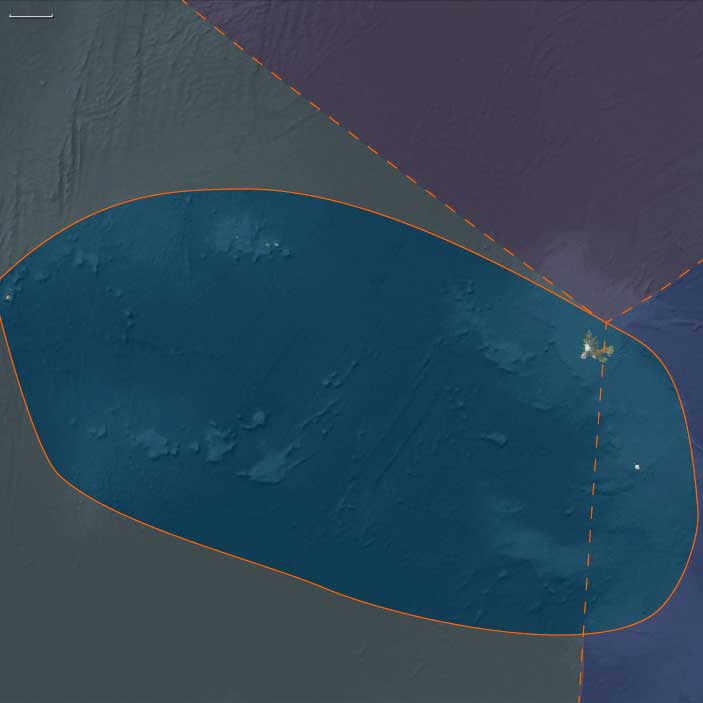

The Southeast Indian Ocean realm includes Kerguelen east of 70° E, Heard Island, and the McDonald Islands—a remote arc of volcanic summits, fjorded coasts, and glacial remnants on the northern fringe of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC).

-

Kerguelen’s eastern plateaus had become a network of deglaciated valleys, lakes, and fjords, with new tundra spreading on lee slopes.

-

Heard Island’s Big Ben massif, though still glacier-crowned, now fed proglacial streams through dark ash and gravel plains.

-

The McDonald Islands persisted as low, surf-scoured volcanic stacks, periodically dusted with fresh tephra.

Together these islands formed a mildly warming, biologically awakening corridor between Antarctica and Australasia.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Hypsithermal warm maximum brought temperatures slightly above late-glacial levels and sea levels nearing the modern mark.

Westerly winds stayed strong but became more seasonally regular, producing shorter winters and longer ice-free summers.

Glaciers on Kerguelen retreated into high cirques; Heard retained summit ice but with episodic surges and retreats that refreshed mineral soils below.

Occasional ashfalls from Big Ben and the McDonald Islets’ eruptions renewed nutrient supply, speeding colonization on sheltered slopes.

Subsistence & Settlement

No human presence yet reached these latitudes.

Instead, the mid-Holocene saw a surge of biotic colonization and ecological diversification:

-

Vegetation: cushion plants, mosses, lichens, and hardy grasses spread inland; peat-forming sedges occupied saturated hollows.

-

Fauna: penguin rookeries multiplied on shingle terraces; elephant and fur seals occupied the newly ice-free beaches; albatrosses and petrels nested on higher benches.

-

Ecosystems: guano enrichment created localized fertility “islands,” supporting invertebrate and microbial blooms; in coastal shallows, kelp forests stabilized as year-round feeding habitats.

Technology & Material Culture

No evidence of human visitation exists. Beyond this subantarctic margin, Holocene societies on other continents adopted microlithic toolkits, early ceramics, and complex fishing gear, but none possessed the cold-weather clothing, open-ocean craft, or high-caloric provisioning systems that would have made survival here feasible.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Ecological linkages substituted for human trade:

-

The ACC and associated subantarctic fronts funneled planktonic blooms around the islands.

-

Baleen whales, fur seals, and penguins migrated through these nutrient corridors each summer.

-

Wide-ranging seabirds connected Heard, McDonald, and eastern Kerguelen with feeding grounds toward Antarctica and southern Australasia, forming a single circumpolar metapopulation network.

These flows created biological highways that paralleled, in non-human form, the sea routes future voyagers would someday follow.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

There is no human symbolic record, yet ecological repetition lent the landscape its own temporal rhythm:

nesting cycles, molt seasons, volcanic pulses, and glacial surges created patterns of renewal that gave these islands their natural “calendar of return.”

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Life persisted through rapid recolonization and flexible reproduction:

-

Vegetation recovered swiftly after ashfall and storm scour.

-

Seal and penguin colonies relocated with beach and ice changes.

-

Peat development buffered moisture and temperature, enhancing habitat heterogeneity.

Disturbance, rather than stability, sustained the system—a self-renewing mosaic maintained by wind, ice, and life itself.

Long-Term Significance

By 4,366 BCE, the Southeast Indian Ocean islands had reached near-modern coastlines and hosted mature subantarctic ecosystems: glaciers confined to summits, peat in basins, and dense rookeries along ice-free shores.

Though unvisited by humankind, these islands already functioned as critical biological nodes within the Southern Ocean’s migratory web—a natural laboratory where volcanic renewal, glacial retreat, and marine fertility combined to sustain one of the planet’s most resilient ecological frontiers