Southern Africa (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late …

Years: 28577BCE - 7822BCE

Southern Africa (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene — Rising Seas, Flood Pulses, and Shell-Midden Shores

Geographic & Environmental Context

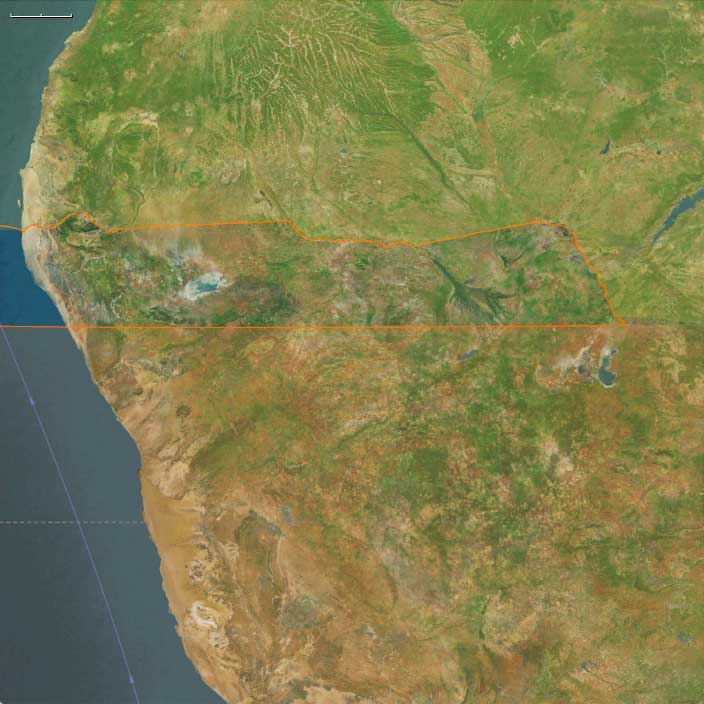

During the long swing from the Last Glacial Maximum to the Early Holocene, Southern Africa cohered as a single water-anchored world.

Two complementary spheres organized lifeways:

-

Temperate Southern Africa — the Cape littoral and fynbos, Namaqualand, Highveld grasslands, Drakensberg–Lesotho massif, Karoo, and the Maputo–Limpopo basins—where rising seas carved modern embayments and lagoons and river valleys remained fertile through climatic swings.

-

Tropical West Southern Africa — the Okavango Delta, Zambezi–Chobe–Cuando/Linyanti–Caprivi wetlands, the Etosha Pan system and Owambo/Cuvelai drains, and the fog-nourished Skeleton Coast—an aquatic–savanna frontier driven by flood pulses and ITCZ rains.

Together these belts formed a ridge–river–coast continuum: shell-rich coves and estuaries at the Cape, grassland and spring corridors inland, and pulsing floodplains and pans to the north.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Bølling–Allerød (c. 14,700–12,900 BCE): Warmer, wetter conditions greened fynbos and Highveld grasslands; Okavango inundations broadened and Caprivi wetlands expanded; woodland belts thickened around Etosha and along the Owambo/Cuvelai drains.

-

Younger Dryas (c. 12,900–11,700 BCE): A brief cool–dry pulse contracted marsh edges and inland water bodies; coastal reliance intensified along the Cape and Namaqualand; floodplain use narrowed to perennial channels and levees.

-

Early Holocene (after 11,700 BCE): Climatic stabilization brought stronger summer rains in the north and reliable winter–spring moisture in the south; flood regimes regularized, lagoons matured, and grasslands recovered.

Subsistence & Settlement

A continent-spanning broad-spectrum portfolio matured, balancing semi-sedentary anchoring with seasonal mobility:

-

Coasts (Temperate south): Strandloper adaptations flourished—large shell middens formed along the Cape and Namaqualand, with fish, mussels, limpets, seals, and seabirds as staples. Semi-sedentary cove camps persisted near rich shorelines and estuaries; inland rounds targeted antelope and dug geophytes in fynbos and grasslands.

-

Floodplains & pans (Tropical west): Semi-recurrent levee camps followed fish runs (catfish/tilapia), flood-recession grazing of antelope, and riparian fruits. The Caprivi supported large wet-season encampments on high levees; Etosha margin hunts focused on springbok, zebra, oryx near permanent water; the Skeleton Coast remained a short-visit zone for carrion and shellfish.

Across both spheres, settlement knit together resource-rich nodes—coves, levees, springs, and rock shelters—reoccupied across generations.

Technology & Material Culture

Toolkits were light, durable, and tuned to water:

-

Microlithic bladelets and backed segments for composite arrows and spears.

-

Fish gorges, bone harpoons, woven basket traps, and stake weirs for estuary and floodplain capture.

-

Grinding slabs for wild plant processing; basketry and cordage for transport and drying racks.

-

Ostrich eggshell (OES) flasks for water carriage and abundant OES beads as exchange media.

-

Early rafts/dugouts likely in calm estuaries and distributaries.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Mobility braided coasts, valleys, pans, and deltas into one exchange field:

-

Coastal corridors linked shell-midden coves with river mouths and inland passes to the Highveld and Drakensberg.

-

Flood-ridge “causeways” among Okavango palm islands, Caprivi levee paths, and Omuramba routes to Etosha organized pulse-following rounds.

-

The Maputo–Limpopo system and interior river valleys moved beads, pigments, dried fish, and hides between grassland and shore.

These routes created redundancy: when drought pinched a basin or a run failed, another habitat or partner camp stabilized supply.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Symbolic life was vivid and place-anchored:

-

Rock art in Drakensberg and Cederberg shelters flourished—polychrome animal–human scenes, trance dances, and eland-linked ceremonies.

-

Shell middens functioned as ancestral markers at coastal landings; bead strings and pigment caches accumulated at island groves and pan-edge shelters in the north.

-

Seasonal feasts at fish peaks and flood-begin events renewed access rules to weirs, springs, and groves—ritual governance of resources.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Security rested on storage + scheduling + multi-ecozone use:

-

Smoked/dried fish and meats, rendered fats, roasted seeds, and stored geophytes buffered lean months and Younger Dryas stress.

-

Seasonal anchoring at rich coasts and pulse-following mobility across wetlands and pans spread risk.

-

Edge-habitat focus (back-bar lagoons, riparian woods, pan margins) maximized predictable returns as conditions shifted.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, Southern Africa had stabilized as a water-anchored forager world: shell-midden communities lined the temperate coasts, and floodplain societies tuned lifeways to the Okavango–Caprivi–Etosha pulse. The shared operating code—portfolio subsistence, storage, seasonal anchoring with mobile spokes, bead-mediated exchange, and shrine-marked tenure—set the durable foundation for later Holocene traditions of coastal strandlopers, floodplain specialists, and, eventually, pastoral and farming horizons on the distant skyline.

Groups

Topics

Commodoties

- Fish and game

- Weapons

- Hides and feathers

- Gem materials

- Colorants

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Strategic metals