West Polynesia (1684–1827 CE): Maritime Chiefdoms, Kava …

Years: 1684 - 1827

West Polynesia (1684–1827 CE): Maritime Chiefdoms, Kava Ceremonies, and the First Currents of Change

Geography & Environmental Context

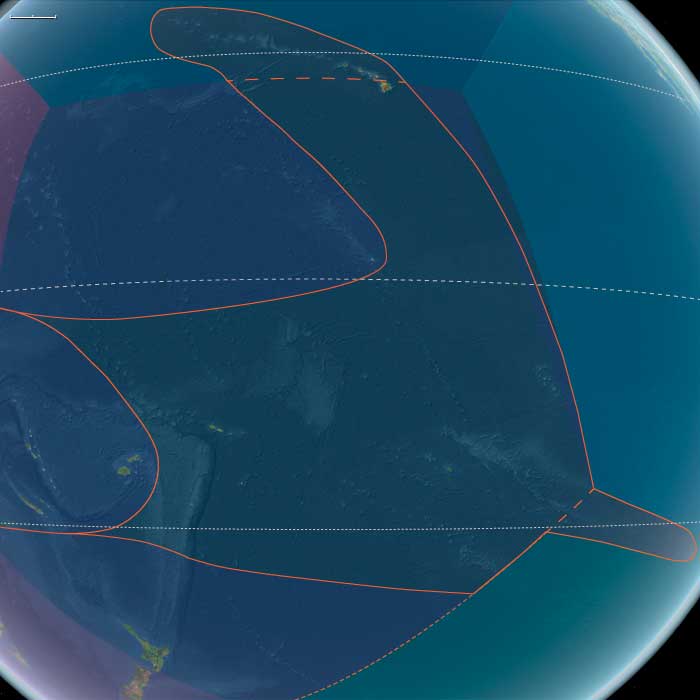

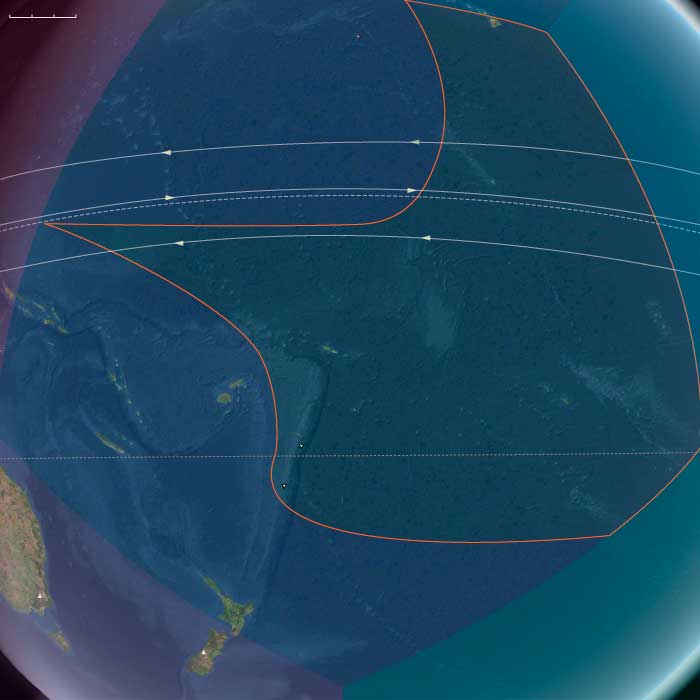

West Polynesia includes the Big Island of Hawai‘i, Tonga, Samoa, Tuvalu, Tokelau, the Cook Islands, and French Polynesia (Tahiti, the Society Islands, the Marquesas, and the Tuamotus). Anchors include Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea on Hawai‘i, the Tongatapu lowlands, the Upolu ridges of Samoa, the fertile valleys of Tahiti, and the dramatic Marquesan cliffs. The subregion blends volcanic high islands with lush valleys and coral atolls sustained by lagoons and reefs, producing varied but interconnected ecological zones.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The tropical climate was governed by trade winds and seasonal rainfall. The Little Ice Age imposed episodes of drought and storm intensification, stressing fragile atolls like Tokelau and Tuvalu. Cyclones periodically damaged breadfruit groves and devastated coastal settlements. Yet volcanic soils in Hawai‘i, Samoa, and Tahiti remained highly productive, and marine ecosystems continued to yield abundant fish, shellfish, and sea mammals.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Hawai‘i (Big Island): Expansive dryland field systems stretched across the Kona and Kohala slopes, producing sweet potatoes and gourds, while irrigated taro terraces filled valleys. Massive fishponds (loko i‘a) along the coasts supplied mullet and milkfish.

-

Tonga and Samoa: Settlements combined irrigated taro and yam cultivation with breadfruit, coconut, and banana groves. Fortified villages and chiefly compounds reinforced political hierarchies.

-

Tuvalu and Tokelau: Subsistence depended on pulaka pits (taro grown in excavated freshwater lenses), coconuts, and lagoon fishing.

-

Cook Islands and Society Islands: Fertile valleys of Tahiti and Rarotonga supported intensive horticulture, with irrigated taro and yam systems sustaining dense populations.

-

Marquesas: Breadfruit and dryland crops underpinned large valley populations, with ceremonial centers anchoring political and ritual life.

Settlements were clustered along coasts and valleys, often marked by marae or heiau temple complexes that linked political power to sacred authority.

Technology & Material Culture

West Polynesians developed sophisticated technologies for both land and sea:

-

Double-hulled voyaging canoes enabled inter-island travel and warfare.

-

Stone adzes and basalt tools shaped temples, canoes, and agricultural terraces.

-

Fishponds in Hawai‘i and irrigation works across Samoa and Tahiti displayed advanced engineering.

-

Feather cloaks, woven mats, tapa cloth, and tattooing embodied both artistry and social identity.

-

Monumental marae temples in Tahiti, such as Taputapuātea on Ra‘iātea, served as religious and political centers binding communities across the Pacific.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Voyaging, exchange, and rivalry shaped the subregion:

-

Hawai‘i: Chiefs expanded territories through canoe warfare and alliances, with Hawai‘i Island increasingly dominant by the late 18th century.

-

Tonga: Extended influence into Samoa, ʻUvea, and Fiji through marriage, tribute, and ritual exchange.

-

Samoa: Served as a cultural heartland, exporting prestige goods and maintaining extensive kinship ties.

-

Tahiti and the Society Islands: Became hubs linking the Tuamotus, Cooks, and Marquesas, central to ritual exchange and long-distance voyaging.

-

European arrivals: From the 1760s onward, Dutch, British, and French ships entered West Polynesian waters. Captain James Cook charted Tahiti and Hawai‘i, and missionaries arrived soon after, bringing new goods, firearms, and faiths that disrupted existing balances.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Ritual life remained vibrant and elaborate:

-

In Hawai‘i, the kapu system regulated hierarchy and resources; ceremonies in large heiau temples honored Kū (warfare) and Lono (fertility).

-

In Tonga and Samoa, kava ceremonies cemented chiefly authority and diplomacy, while finely woven mats (ʻie tōga) symbolized wealth and status.

-

In Tahiti, the ʻOro cult rose to prominence, with red feather belts (maro ʻura) consecrating paramount chiefs at Taputapuātea.

-

In the Marquesas, tattooing reached peak elaboration, inscribing bodies with genealogical and spiritual narratives.

-

Oral traditions, chants, and genealogies across the subregion bound communities to divine ancestors and sacred landscapes.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Islanders developed ingenious systems to buffer ecological stress:

-

Dryland stone alignments and mulching in Hawai‘i stabilized crops against drought.

-

Pulaka pits on atolls ensured food even when rains failed.

-

Fishponds and storage pits provided surpluses for redistribution.

-

Tribute systems and ceremonial redistribution spread risk, ensuring stability across chiefdoms.

-

Inter-island kinship ties enabled recovery after storms or famine, with canoes carrying aid and tribute between islands.

Transition

Between 1684 and 1827, West Polynesia saw the consolidation of powerful chiefdoms and the flowering of ritual and engineering traditions that supported dense populations and dynamic exchange. Yet this was also the age when European contact intensified. Cook’s voyages, followed by whalers, traders, and missionaries, brought iron, firearms, and epidemic diseases that destabilized established systems. The subregion remained culturally strong and resilient, but by 1827 its societies were already negotiating new realities in which oceanic seafaring and marae ritual now intersected with global commerce and colonial ambitions.

Groups

- Hawaiʻi

- Fiji

- Polynesians

- Samoan, or Navigators Islands

- Tahitians

- Ellice Islands/Tuvalu

- Cook Islanders

- Hawaiians, Native

- Marquesas Islands

- Tokelau

- Tonga, Kingdom of

Topics

Commodoties

- Rocks, sand, and gravel

- Fish and game

- Hides and feathers

- Grains and produce

- Fibers

- Ceramics

- Salt

- Lumber