Polynesia (1684 – 1827 CE) Voyaging …

Years: 1684 - 1827

Polynesia (1684 – 1827 CE)

Voyaging Chiefdoms, Sacred Landscapes, and the First Global Intrusions

Geography & Environmental Context

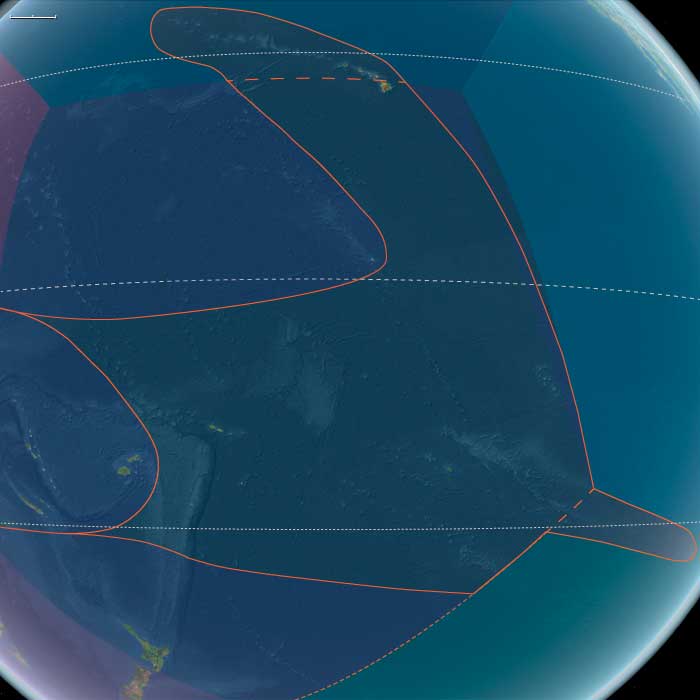

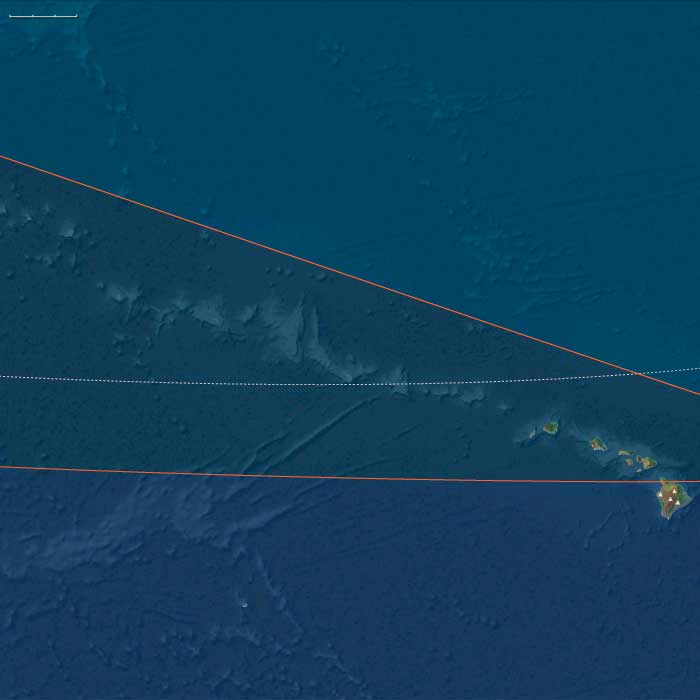

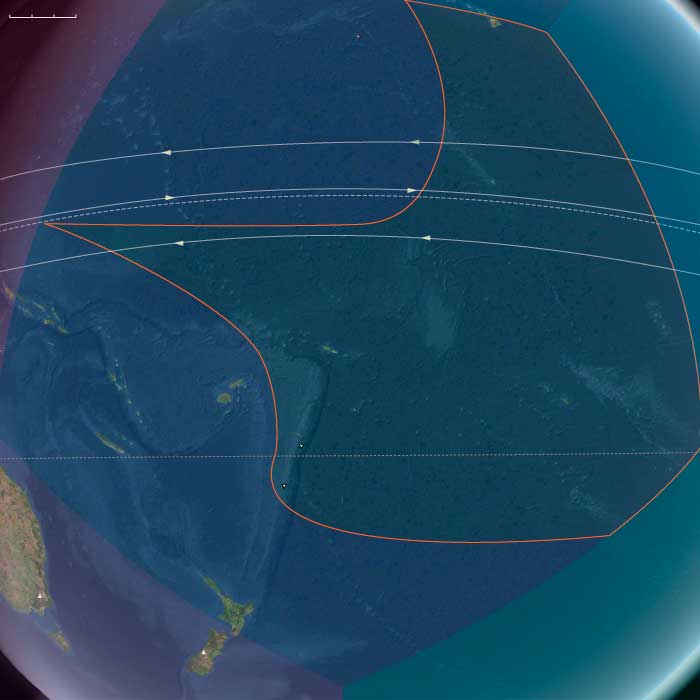

Polynesia, comprising three enduring subregions—North Polynesia (the Hawaiian Islands except the Big Island, plus Midway Atoll), West Polynesia (the Big Island, Tonga, Samoa, Tuvalu, Tokelau, the Cook Islands, and French Polynesia), and East Polynesia (Rapa Nui and the Pitcairn group)—formed a vast oceanic triangle defined by volcanic high islands and low coral atolls. Fertile valleys, extensive reef systems, and lagoons sustained dense populations through intensive agriculture and aquaculture. The Little Ice Age continued to influence rainfall variability and cyclone frequency, producing alternating pulses of abundance and hardship across the tropics.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

Trade-wind patterns brought stable warmth and seasonal rains, but localized droughts—especially on leeward coasts and atolls—stressed food systems. Cyclones periodically ravaged Tuvalu, Tokelau, and the Cook Islands, while volcanic activity in Hawai‘i and seismic swells in the Marquesas altered landscapes. Deforestation on Rapa Nui accelerated erosion, and soil exhaustion compelled adaptive intensification elsewhere: mulching, irrigation, and fishpond engineering countered climatic strain.

Subsistence & Settlement

Agriculture and fishing were refined into resilient, region-spanning systems:

-

High-island cultivation: Wet-field taro terraces, dryland sweet-potato plots, and breadfruit orchards anchored subsistence on O‘ahu, Maui, Tahiti, Upolu, and Savai‘i.

-

Fishpond and lagoon management: Coastal loko i‘a in Hawai‘i and reef tenure systems across Samoa and Tonga produced stable protein supplies.

-

Atoll lifeways: Pulaka pits in Tuvalu and Tokelau, coconuts, and preserved breadfruit underpinned survival.

-

Eastern limits: On Rapa Nui, rock-mulched gardens and chicken enclosures maintained yields amid ecological stress; Pitcairn’s horticulture remained modest but enduring.

Village clusters aligned along fertile valleys and coasts, centered on marae or heiau temple complexes that integrated political power with sacred geography.

Technology & Material Culture

Across Polynesia, artistry and engineering flourished:

-

Canoe technology: Double-hulled voyaging canoes sustained inter-island networks.

-

Hydraulic works: Irrigation ditches and fishponds demonstrated ecological mastery.

-

Material arts: Feather cloaks and helmets, tapa cloth, tattooing, and fine mats encoded rank and lineage.

-

Architecture: Massive heiau and marae—Taputapuātea on Ra‘iātea, Pu‘ukoholā on Hawai‘i—served as ceremonial and political nexuses.

-

Stone sculpture: On Rapa Nui, the creation and later cessation of moai carving marked profound cultural transitions.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Voyaging bound the entire region into a single cultural sphere:

-

Inter-island diplomacy and war: Rivalries between O‘ahu, Maui, and Kaua‘i; Tongan influence through tribute and marriage alliances; Samoan cultural diffusion across western archipelagos.

-

Ritual travel: Pilgrimage to sacred centers like Taputapuātea reaffirmed divine sanction for rulers.

-

European arrivals: From Abel Tasman and Samuel Wallis to James Cook and Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, Western ships entered Polynesian waters, charting islands, trading iron and cloth, and introducing epidemics. Whalers and traders extended these circuits by the early nineteenth century.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Religion, performance, and genealogy sustained cohesion:

-

The kapu and tapu systems ordered society through sacred prohibitions.

-

Kava ceremonies in Tonga and Samoa, Makahiki festivals in Hawai‘i, and the ‘Oro cult in Tahiti expressed the unity of ritual, economy, and hierarchy.

-

Oral genealogies and chant traditions (mele, siva, himene) legitimated chiefly descent from gods.

-

Tattoo and dance became living archives of identity, while marae processions dramatized power and continuity.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Polynesians developed intricate safeguards against ecological shocks:

-

Diversified cropping and stone mulching mitigated drought.

-

Fishponds and reef tenure buffered food shortages.

-

Redistributive tribute systems pooled surpluses across districts.

-

Kinship networks functioned as disaster-relief systems, moving food, tools, and ritual specialists after storms or volcanic events.

Even after the introduction of foreign diseases and firearms, adaptive governance and ritual exchange preserved community stability.

Political & Military Shocks

The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries ushered in new conflicts and consolidations:

-

In Hawai‘i, Kamehameha I unified the islands through warfare and diplomacy, forming a centralized kingdom.

-

Tongan monarchs extended influence across western archipelagos; Samoan rivalries balanced matai councils and alliances.

-

European contact disrupted these balances—introducing new weapons, commerce, and missionary influence that began undermining traditional authority.

-

In East Polynesia, slaving raids and foreign landings destabilized isolated communities, while Pitcairn became a hybrid society after the Bounty mutiny (1790).

Transition

Between 1684 and 1827 CE, Polynesia evolved from a self-contained oceanic world of sacred chiefdoms and inter-island networks into a region newly exposed to global exchange. Voyaging, irrigation, and ritual artistry reached their zenith even as epidemics, missionaries, and foreign traders appeared on the horizon. The synthesis of Indigenous resilience and early external intrusion defined this High Modern Age—an era when Polynesian societies stood at once autonomous and increasingly entangled in the world’s widening currents.

Groups

- Hawaiʻi

- Fiji

- Polynesians

- Samoan, or Navigators Islands

- Tahitians

- Ellice Islands/Tuvalu

- Cook Islanders

- Hawaiians, Native

- Marquesas Islands

- Tokelau

- Tonga, Kingdom of

Topics

Commodoties

- Rocks, sand, and gravel

- Fish and game

- Hides and feathers

- Grains and produce

- Fibers

- Ceramics

- Salt

- Lumber