West Polynesia (820 – 963 CE): Tongan …

Years: 820 - 963

West Polynesia (820 – 963 CE): Tongan Consolidation, Samoan Lineages, and the Emergent Polynesian Exchange Sphere

Geographic and Environmental Context

West Polynesia includes the Big Island of Hawaiʻi, Tonga, Samoa, Tuvalu, Tokelau, the Cook Islands, and French Polynesia (Society Islands and Marquesas).

-

This is the heartland of high volcanic islands with fertile soils (Tonga, Samoa, Society Islands, Marquesas), surrounded by atolls (Tokelau, Tuvalu, northern Cooks) and reef-fringed coasts.

-

The high islands supported intensive agriculture and complex chiefdoms, while the atolls relied on arboriculture, fishing, and voyaging links to maintain subsistence.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

Stable tropical maritime climate, with alternating wet–dry regimes supporting agriculture.

-

Periodic cyclones disrupted low-lying atolls, necessitating resilient exchange systems.

-

Fertile volcanic soils in Tonga, Samoa, and the Societies allowed sustained population growth.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Tonga: The Tuʻi Tonga line began consolidating chiefly authority, organizing labor for large earthworks and fortifications. Ranked aristocracies became increasingly formalized, laying the basis for later regional hegemony.

-

Samoa: Power remained dispersed among extended kin-groups and matai (chiefs), who balanced local authority with island-wide councils; Samoan ritual and lineage systems would heavily influence neighboring archipelagos.

-

Society Islands (Tahiti, Raiatea, Bora Bora): Early marae temple complexes emerged as centers of chiefly ritual, linking community fertility to divine sanction.

-

Marquesas: High valleys hosted clan-based polities that invested in monumental meʻae ritual grounds and developed distinctive art traditions.

-

Cook Islands, Tuvalu, Tokelau: Smaller-scale chiefdoms depended on sailing links with Samoa and Tonga to balance resource limitations.

-

Big Island of Hawaiʻi: Distinct chiefly lineages emerged; agriculture in Kona and Hilo districts supported growth, though Hawaiian polities remained localized compared to southern West Polynesia.

Economy and Trade

-

Agriculture: Taro, yam, breadfruit, and banana cultivation formed dietary bases; sweet potato (ʻuala) began spreading in parts of Polynesia.

-

Arboriculture and animal husbandry: Coconut and pandanus groves supported atoll life; pigs, dogs, and chickens were husbanded on high islands.

-

Exchange networks: Canoe voyages linked Tonga, Samoa, and Fiji, forming a central Polynesian interaction sphere; basalt adzes, fine mats, shell ornaments, and preserved foods moved between islands.

-

Specialized craft production: Samoan fine mats, Tongan barkcloth, and Marquesan carving traditions circulated as prestige items.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Horticulture: Irrigated taro pondfields in valleys; shifting gardens on slopes with stone alignments.

-

Fishing and reef exploitation: Outrigger canoes with trolling lines, nets, and hooks harvested pelagic and reef fish.

-

Navigation: Star compasses, swell-reading, and bird-flight observation guided long voyages; voyaging canoes connected West Polynesia to Micronesia and East Polynesia.

-

Architecture: Earthwork fortifications in Tonga, coral and basalt marae foundations in Societies, timber-framed meeting houses in Samoa.

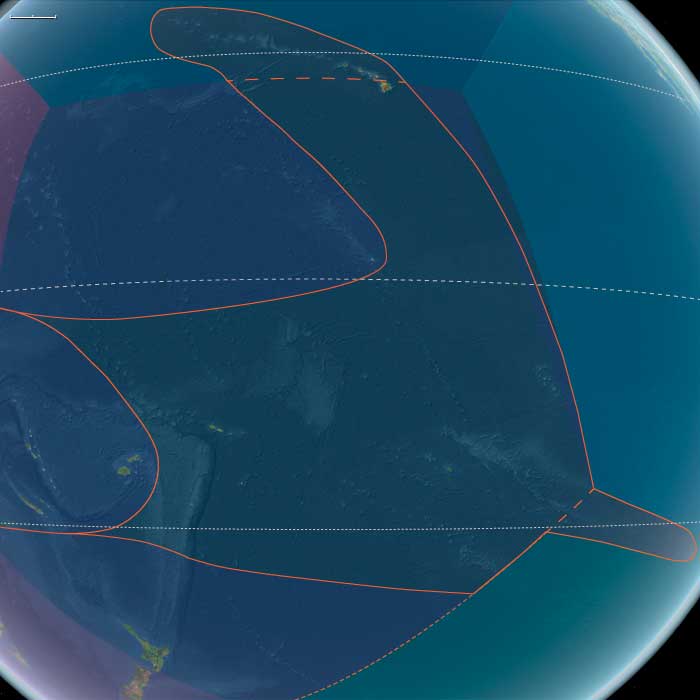

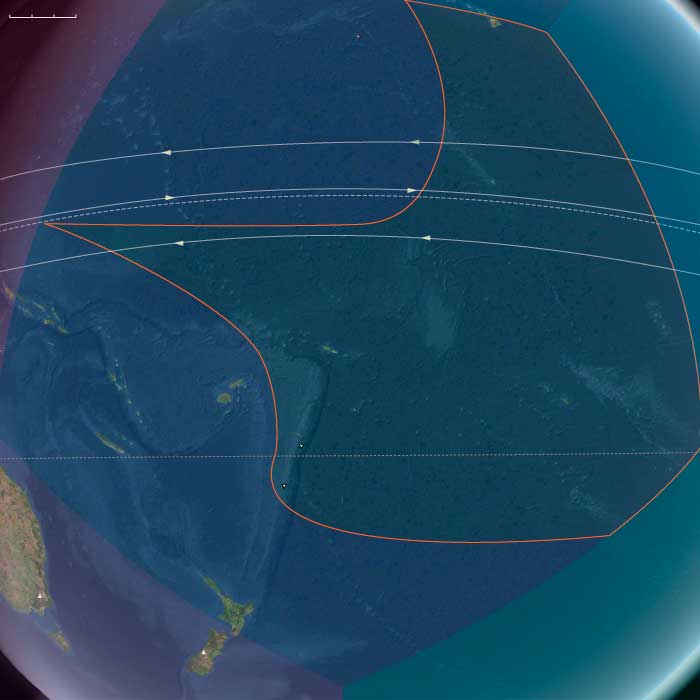

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

The Tonga–Samoa–Fiji triangle was the core of Polynesian interaction, sustaining political marriages and ritual alliances.

-

Voyaging reached outward to Cooks, Societies, Marquesas, and likely reinforced ties with Micronesia.

-

Hawaiʻi (Big Island) remained peripherally connected, but oceanic routes carried influences northward.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Marae (Societies) and meʻae (Marquesas) anchored ritual life; deities linked fertility, sea, and warfare.

-

Tonga advanced the concept of divine chiefs (Tuʻi Tonga) as intermediaries with gods.

-

Samoa emphasized lineage authority and ancestor veneration, expressed in oratory and fine mats.

-

Ritualized voyaging underscored sacred geography, binding islands into a shared cosmology.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Cyclone resilience through arboriculture (breadfruit, coconut) and inter-island exchange.

-

Diversified diets of root crops + arboriculture + reef harvests buffered ecological shocks.

-

Chiefly redistribution of surpluses during rituals stabilized inequalities and reinforced alliance networks.

Long-Term Significance

By 963 CE, West Polynesia had emerged as the political and cultural engine of Polynesia:

-

Tonga developed the earliest hierarchical polity with external ambitions.

-

Samoa perfected lineage-based political balance.

-

Societies and Marquesas created monumental and artistic traditions anchoring ritual life.

-

Inter-island voyaging and marriage alliances linked the region into a coherent Polynesian exchange sphere, projecting influences toward Micronesia, East Polynesia, and even Hawaiʻi.

Groups

- Hawaiʻi

- Fiji

- Samoan, or Navigators Islands

- Tahitians

- Ellice Islands/Tuvalu

- Cook Islanders

- Hawaiians, Native

- Marquesas Islands

- Society Islands

- Tokelau

- Tonga, Kingdom of