Zuo Zongtang

Chinese diplomat and military leader

Years: 1812 - 1885

Zuo Zongtang (November 10, 1812 - September 5, 1885), spelled Tso Tsung-t'ang in Wade-Giles and known simply as General Tso in the West, is a Chinese diplomat and military leader in the late Qing Dynasty.

He was born in Wenjialong, north of Changsha in Hunan province.

He serves in China's northwestern regions, quelling the Dungan revolt and various other disturbances.

He serves with distinction during the Qing Empire's civil war against the Taiping Rebellion, in which it is estimated 20 million people die.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 21 total

Zuo Zongtang is governor-general of Chekiang and Fukien and one of the most powerful figures in China by 1863.

Born into a well-connected, scholarly family, he had helped organize local defense forces when the Taiping Rebellion began to spread through South China after 1850.

A former protégé of Zeng Guofan, Zuo had soon become one of the top imperial commanders.

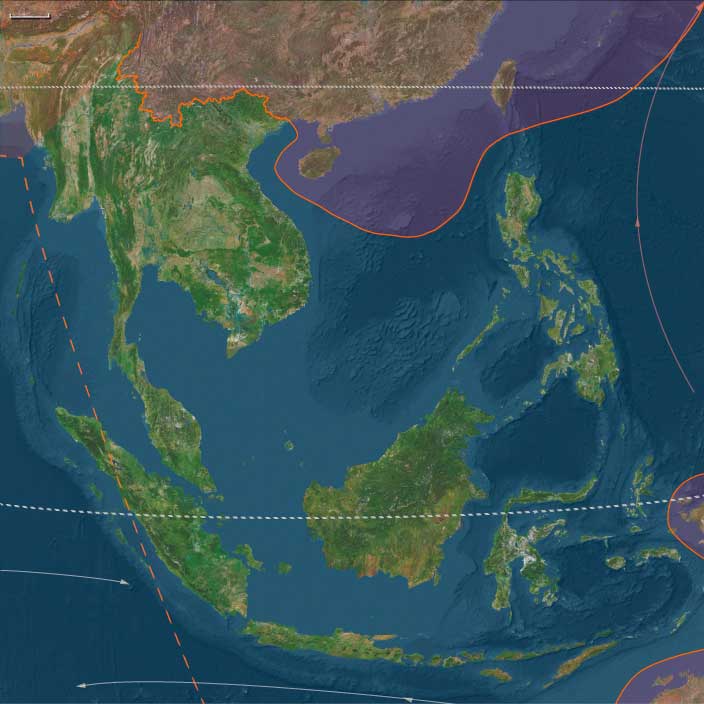

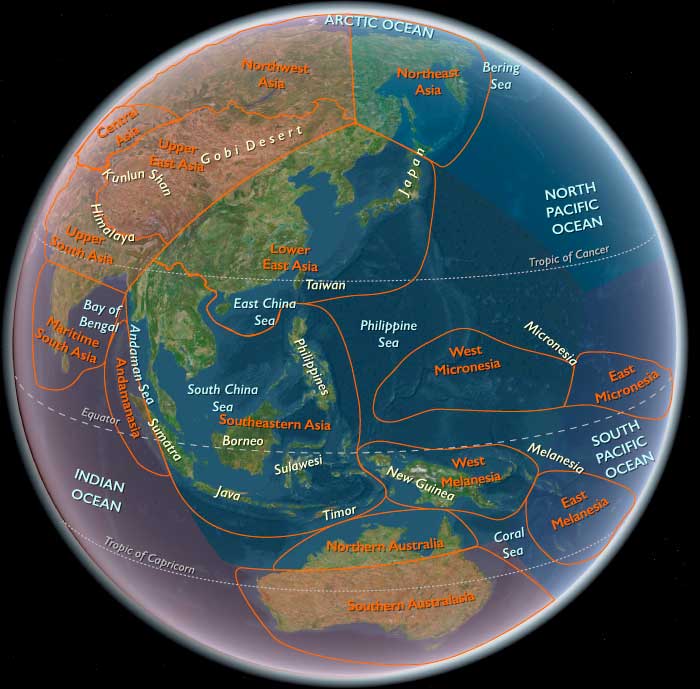

Maritime East Asia (1864–1875 CE): Restoration, Modernization, and Rising Nationalism

Between 1864 and 1875 CE, Maritime East Asia—encompassing lower Primorsky Krai, the Korean Peninsula, the Japanese Archipelago south of northern Hokkaido, Taiwan, and southern, central, and northeastern China—experiences critical efforts at restoration and modernization, rising nationalist sentiments, and significant political restructuring, laying the foundations for profound regional transformations.

China: The Self-Strengthening Movement and Foreign Encroachments

Following the devastating Taiping Rebellion, Qing China embarks on the Self-Strengthening Movement, driven by scholar-generals such as Li Hongzhang and Zuo Zongtang. These leaders advocate adopting Western science, technology, and military strategies to strengthen China internally while preserving traditional political structures. Between 1861 and 1875, China sees the establishment of modern arsenals, shipyards, factories, schools, and improved diplomatic methods.

However, modernization efforts face significant internal resistance. The conservative bureaucracy, still deeply influenced by Neo-Confucian traditions, slows comprehensive reform. Simultaneously, foreign pressures intensify: Russia seizes significant territories in Manchuria, while Western powers further consolidate economic concessions through extraterritorial rights and treaty ports, severely limiting Qing sovereignty.

The Tongzhi Restoration (1862–1874), under the guidance of Empress Dowager Cixi, seeks to stabilize Qing rule through cautious reform and restoration of traditional authority. Yet, despite modest improvements, Qing China continues to struggle with internal fragmentation and external vulnerabilities.

Japan: The Meiji Restoration and Rapid Transformation

In Japan, internal conflicts culminate dramatically with the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate and the establishment of the Meiji Restoration in 1868. This marks the end of over two centuries of feudal rule, and power formally returns to the imperial court under Emperor Mutsuhito, who reigns as Emperor Meiji. The Restoration fundamentally restructures Japanese governance, aiming to modernize and centralize authority rapidly.

The Charter Oath of 1868 outlines Japan’s new goals: establishing deliberative assemblies, allowing social mobility, embracing international knowledge, and discarding outdated customs. Feudal domains (han) are abolished and replaced by prefectures, dramatically centralizing authority. Comprehensive reforms reshape the social order, economy, military, and education system, heavily influenced by Western models.

Influential leaders such as Okubo Toshimichi, Saigo Takamori, Kido Koin, and Iwakura Tomomi emerge as architects of modernization, promoting industrialization, infrastructure expansion, military enhancement, and international diplomatic engagement. A landmark diplomatic mission, the Iwakura Mission (1871–1873), travels extensively through the United States and Europe to learn and implement Western governance practices, technology, and education.

Korea: Continued Isolation and Internal Strife

Joseon Korea maintains its stringent isolationist policies amid escalating Western pressure on neighboring nations. Harsh persecution of Christians continues, reflecting deep suspicion toward foreign influence. Economic hardship intensifies due to governmental inaction and societal rigidity, fueling internal unrest and widespread poverty.

The rigid isolation contributes to deepening internal instability, setting the stage for growing social unrest and major rebellions in subsequent decades. Despite awareness of international developments in Japan and China, the Joseon court resolutely resists change, increasingly alienating progressive factions within the kingdom.

Legacy of the Era: Foundations of Modernization and Persistent Challenges

The years 1864 to 1875 CE witness crucial steps toward modernization and nation-building in Mariime East Asia. While Japan rapidly transforms into a centralized, modern nation-state, China's conservative approach limits the effectiveness of its reforms, leaving it vulnerable to continued external exploitation and internal tensions. Meanwhile, Korea’s determined isolation preserves immediate stability at the cost of long-term preparedness, foreshadowing severe challenges in the rapidly changing international environment. This era thus profoundly shapes the region’s trajectory, determining each nation’s path into the late nineteenth century.

The effort to graft Western technology onto Chinese institutions becomes known as the Self-Strengthening Movement.

The movement is championed by scholar-generals like Li Hongzhang (1823-1901) and Zuo Zongtang (1812-85), who had fought with the government forces in the Taiping Rebellion.

From 1861 to 1894, leaders such as these, now turned scholar-administrators, will be responsible for establishing modern institutions, developing basic industries, communications, and transportation, and modernizing the military, but despite its leaders' accomplishments, the Self-Strengthening Movement does not recognize the significance of the political institutions and social theories that had fostered Western advances and innovations.

This weakness leads to the movement's failure.

Modernization during this period would have been difficult under the best of circumstances.

The bureaucracy is still deeply influenced by Neo-Confucian orthodoxy.

Chinese society is still reeling from the ravages of the Taiping and other rebellions, and foreign encroachments continue to threaten the integrity of China.

Russia, which had been expanding into Central Asia, had taken the first step in the foreign powers' effort to carve up the Qing Empire.

By the 1850s, tsarist troops also had invaded the Heilongjiang watershed of Manchuria, from which their countrymen had been ejected under the Treaty of Nerchinsk.

The Russians had used the superior knowledge of China they had acquired through their century-long residence in Beijing to further their aggrandizement.

In 1860 Russian diplomats had secured the secession of all of Manchuria north of the Heilongjiang and east of the Wusuli Jiang (Ussuri River).

Foreign encroachments had increased after 1860 by means of a series of treaties imposed on China on one pretext or another.

The foreign stranglehold on the vital sectors of the Chinese economy is reinforced through a lengthening list of concessions.

Foreign settlements in the treaty ports becomes extraterritorial—sovereign pockets of territories over which China has no jurisdiction.

The safety of these foreign settlements is ensured by the menacing presence of warships and gunboats.

Two ports, Tianjin and Shanghai, had been opened to Western trade as a result of treaties with the Western powers.

In Shanghai, the British settlement to the south of Suzhou Creek (northern Huangpu District) and the American settlement to the north (southern Hongkou District) had joined in 1863 in order to form the Shanghai International Settlement.

France, having opted out of the Shanghai Municipal Council, maintains its own concession to the south and southwest.

Two officials titled Commissioner of Trade for the southern and northern ports, respectively, have been appointed to administer foreign trade matters at the newly opened ports.

Although the ostensible reason for the establishment of these two government offices had been to administer the new treaty ports, the underlying reasons for their establishment are more complicated: these superintendents are supposed to confine to the ports all diplomatic dealings with foreigners, rather than burdening Peking with them.

The authority of the commissioners will also come to include the overseeing of all new undertakings utilizing Western knowledge and personnel; thus, they will become the coordinators of most self-strengthening programs.

The concern with "self-strengthening" of China had been expressed by Feng Guifen (1809-1874) in a series of essays presented by him to Zeng Guofan in 1861.

Zeng, in his diaries, mentions directing his self-strengthening rhetoric to the call for modernization.

The movement can be divided into three phases.

The first, which will last from 1861 to 1872, emphasizes the adoption of Western firearms, machines, scientific knowledge and training of technical and diplomatic personnel through the establishment of a diplomatic office and a college.

Feng, who had gained military experience commanding a volunteer corps in the anti-Taiping campaign, in 1860 had moved to Shanghai, where he had been greatly impressed by Western military techniques.

The most important goal of the Self-Strengthening Movement is the development of military industries; namely, the construction of military arsenals and of shipbuilding dockyards to strengthen the Chinese navy.

This program is spearheaded by regional leaders like Zeng Guofan who, employing Yung Wing, establishes the Shanghai arsenal, ...

...Li Hongzhang, who will build the Nanking and Tientsin Arsenal, and ...

...Zuo Zongtang, who constructs the Fuzhou Dockyard.

The arsenals are established with the help of foreign advisors and administrators, such as ..

...Léonce Verny, who has helped build the Ningbo Arsenal from 1862-64.

These military initiatives are largely sponsored by the government and, as such, suffer from the usual bureaucratic inefficiency and nepotism.

Many of the Chinese administrative personnel are sinecure holders who get themselves on the payroll through influence.

The locus of power shifts, after the final defeat of the Taiping at Nanking in 1864, from the Manchu to those Chinese who have played the main part in putting down the rebellions.

The Muslim rebels of Shensi, defeated by the Imperial army, flee to Kansu, which becomes the main theater of fighting.

There are many independent Muslim leaders in Shensi and Kansu, but they have neither a common headquarters nor unified policy, and there are no all-out revolutionaries.

Pacification of rebellious Shensi and Kansu is delayed because the Imperial camp is preoccupied with the Taiping and the Nien and cannot afford the expenditure needed for an expedition to the remote border provinces.

In 1866, Zuo Zontang is made governor-general of Shensi and Kansu to quell the Muslim rebels there with part of the Huai Army.

Encouraged by the Nien invading Shensi at the end of 1866, the core of the rebel troops return from Kansu to Shensi, and sporadic clashes continue in the two provinces.