East Africa (820 – 963 CE): Swahili …

Years: 820 - 963

East Africa (820 – 963 CE): Swahili Beginnings, Highland Christianity, and the Great Lakes Mosaic

Geographic and Environmental Context

East Africa extended from the Somali coast to the Zambezi plateau, encompassing the Swahili littoral, the Comoros and Madagascar, and the highlands and lakes of the interior.

-

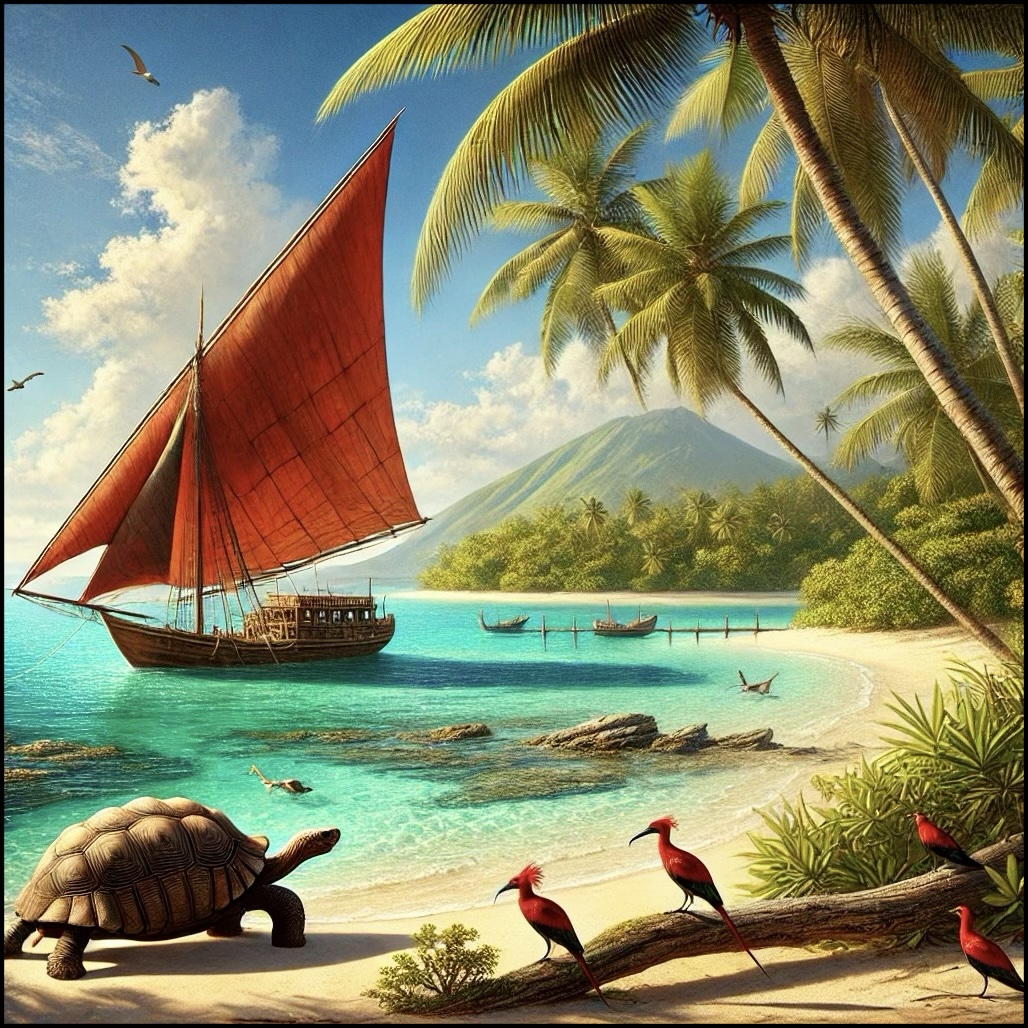

Maritime East Africa stretched from southern Somalia through Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, and the offshore islands—Lamu, Pate, Mombasa, Zanzibar, Pemba, Mafia, Kilwa Kisiwani, Songo Mnara, and the Comoros, as well as Madagascar, Seychelles, and the Mascarenes.

-

Interior East Africa reached from Eritrea and Ethiopia through Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, South Sudan, and the Zambezi–Zimbabwe–Malawi basins.

Across this region, monsoonal winds, rifted uplands, and wetland corridors linked oceanic trade with inland agrarian and pastoral networks.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The onset of the Medieval Warm Period brought relatively stable monsoons and favorable rainfall:

-

Coastal lowlands and river valleys sustained rice, banana, and millet cultivation.

-

Ethiopian Highlands maintained terrace farming under mild conditions.

-

Great Lakes basins offered abundant fish, fertile volcanic soils, and year-round agriculture.

-

Madagascar’s central plateau experienced reliable rainfall, supporting mixed rice and cattle economies.

-

Seychelles and Mascarene Islands remained uninhabited, their ecosystems dominated by seabirds, turtles, and endemic flora.

Monsoon stability ensured dependable sailing seasons, tying the region to the wider Indian Ocean world.

Societies and Political Developments

Maritime East Africa: Swahili Settlements and Island Frontiers

-

Along the Swahili coast, early towns such as Shanga, Lamu, and Mombasa emerged from Bantu-speaking coastal populations interacting with Arab and Persian traders.

-

These settlements evolved into cosmopolitan ports, blending African and Islamic influences and forming the nucleus of the Swahili culture.

-

The Comoros Islands hosted mixed Austronesian–African communities dependent on coconuts, fishing, and small-scale trade.

-

Madagascar was settled by Austronesian voyagers from Island Southeast Asia, who intermarried with African migrants; by the 9th century, highland villages and coastal chiefdoms were established.

-

Seychelles and Mascarene Islands were still uninhabited but served as occasional maritime waypoints for regional navigators.

Interior East Africa: Highland Faith and Great Lakes Foundations

-

In Ethiopia, the Aksumite kingdom had waned, yet Christianity endured in highland principalities sustained by monasteries and churches.

-

Around the Great Lakes, early Urewe pottery cultures transitioned into village-based farming and fishing societies—forerunners of later kingdoms such a Buganda and Bunyoro.

-

Nilotic herders (ancestors of Dinka, Nuer, and Shilluk) prospered along the Upper Nile, balancing cattle herding with seasonal farming.

-

Across the Zambezi corridor, northern Zimbabwe and Zambia saw the growth of millet and cattle-raising communities, prefiguring the complex societies of Great Zimbabwe.

Economy and Trade

-

Maritime exchange:

-

Exports included ivory, tortoise shell, rhinoceros horn, slaves, and forest goods, sent north to Arabia, Persia, and India.

-

Imports comprised glass beads, cloth, metal tools, and ceramics.

-

Madagascar supplied rice, cattle, timber, and aromatic resins, integrated into Swahili coastal trade.

-

-

Inland economies:

-

Agriculture: sorghum, millet, teff, and bananas; ensete (false banana) in Ethiopia; rice in Madagascar.

-

Pastoralism: cattle wealth structured exchange and ritual from South Sudan to Zimbabwe.

-

Trade corridors: ivory and hides moved from interior markets toward the Red Sea and Indian Ocean ports; salt, iron, and copper circulated within the plateau economies.

-

-

The Zambezi–Maputo–Kilwa routes became early arteries of trans-regional commerce, linking interior resources to the Indian Ocean world.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Agriculture and herding: floodplain and terrace farming in the highlands; dryland millet and sorghum in the south; banana and rice cultivation along the coast.

-

Fishing: Great Lakes, Rift Valley, and coastal estuaries supplied year-round food security.

-

Iron smelting: widespread from Ethiopia to Zimbabwe, producing hoes, spearheads, and trade implements.

-

Architecture: wattle-and-daub villages on the mainland; coral and mangrove timber in early Swahili towns; stone foundations appearing in the Zimbabwe plateau uplands.

-

Navigation: sewn-plank dhows and outrigger canoes moved between the coast, islands, and across to Madagascar.

-

Crafts: pottery, woven mats, bead jewelry, and metal tools underpinned both household and trade economies.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Christianity persisted in the Ethiopian Highlands, sustaining monasteries, cross traditions, and local saints’ cults.

-

Indigenous Bantu religions emphasized ancestor veneration, fertility, and rainmaking; cattle and lineage shrines symbolized continuity and wealth.

-

Sanctified nature: sacred groves, hills, and water sources marked boundaries between human and divine realms.

-

Austronesian influences in Madagascar and the Comoros reinforced ancestor worship and spirit mediation through household altars.

-

Along the Swahili coast, Islamic ideas blended with African spirituality, creating a hybrid cosmology that shaped early mosques and burial traditions.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Environmental adaptation: diverse ecologies—coastal, highland, and wetland—enabled communities to shift between agriculture, herding, and fishing according to climate and resource cycles.

-

Monsoon navigation: predictable wind systems allowed coastal cities to synchronize markets with Arabia and India.

-

Agrarian resilience: intercropping and cattle herding buffered droughts; bananas and ensete ensured perennial food sources.

-

Social integration: kinship and exchange networks linked the highlands and coast through caravan and river routes.

-

Cultural synthesis: African, Austronesian, and Islamic elements blended to create flexible, adaptive societies on both sides of the Indian Ocean.

Long-Term Significance

By 963 CE, East Africa had become a continent-spanning corridor of trade, faith, and ecological diversity:

-

Swahili settlements from Shanga to Kilwa were firmly integrated into the Indian Ocean commercial sphere.

-

Madagascar and the Comoros embodied early Austronesian–African synthesis, while the Seychelles and Mascarenes remained ecological frontiers.

-

Ethiopia preserved Christian continuity amid the Islamic expansion around the Red Sea.

-

The Great Lakes and Zambezi–Zimbabwe region nurtured enduring agricultural and pastoral cultures that would evolve into state systems.

The age’s enduring legacy was a maritime–inland continuum: from coral-built ports and dhows riding the monsoon to inland cattle rituals and hilltop monasteries. It laid the foundations for the Swahili urban boom, Zagwe Christian revival, and Zimbabwean monumental architecture that would define East Africa in the centuries to come.

Maritime East Africa (with civilization) ©2024-25 Electric Prism, Inc. All rights reserved.

Groups

- Austronesian peoples

- Bantu peoples

- Arab people

- Persian people

- Somalis

- Madagascar

- Nilotic peoples

- Swahili people

- Comoro Islands

- Islam

- Abbasid Caliphate (Baghdad)

- Abbasid Caliphate (Samarra)

- Abbasid Caliphate (Baghdad)

Commodoties

- Fish and game

- Gem materials

- Glass

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Textiles

- Ceramics

- Strategic metals

- Slaves

- Lumber

- Manufactured goods

- Aroma compounds

- Spices