Southern Africa (909 BCE – 819 CE): …

Years: 909BCE - 819

Southern Africa (909 BCE – 819 CE): Iron Horizons, Cattle Pathways, and Forager Frontiers

Regional Overview

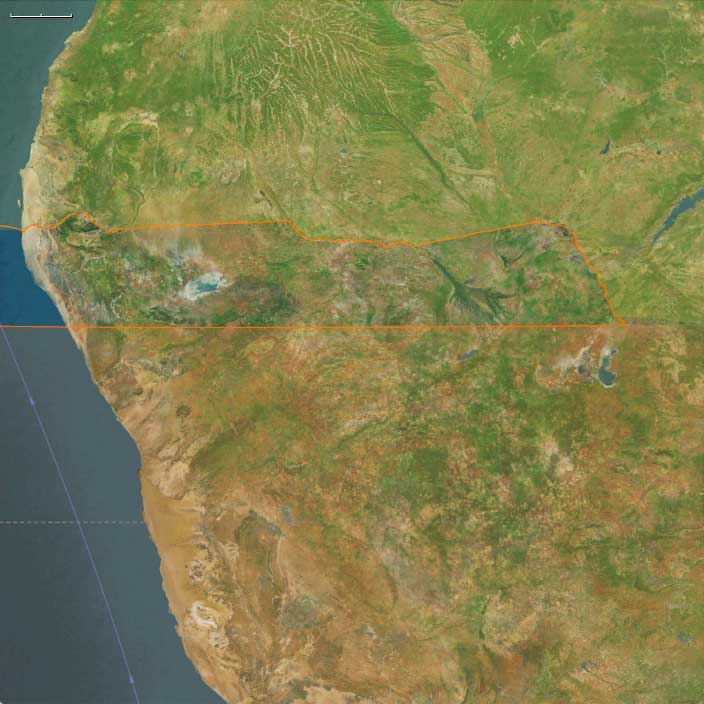

From the fog-shrouded Skeleton Coast to the Drakensberg’s storm-green heights, Southern Africa during the early first millennium BCE to the early first millennium CE was a continent in miniature — a landscape of deserts, grasslands, deltas, and highlands linked by the slow pulse of rivers and the rhythmic migrations of people and herds.

This epoch bridged two long worlds: the enduring forager cosmologies of the San and the iron-working, cattle-herding frontiers advancing southward from equatorial Africa.

By 819 CE, the region had become a broad ecological and cultural hinge between the Atlantic, the Indian Ocean, and the central African tropics — a foundation upon which later kingdoms such as Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe would rise.

Geography and Environment

Southern Africa divided naturally into two complementary environmental realms.

-

The tropical west, encompassing the Okavango Delta, Caprivi–Zambezi wetlands, Etosha Pan, and Skeleton Coast, formed a watery-arid paradox — rich floodplains bordered by desert margins.

-

The temperate south, spanning the Highveld, Drakensberg, Karoo, Namaqualand, and southern Zimbabwe plateau, offered grasslands and seasonal rivers ideal for mixed farming and herding.

Monsoon and Atlantic westerlies delivered alternating wet and dry pulses.

Flooded wetlands and stable aquifers nurtured dense fish and game populations; the Drakensberg and Limpopo valleys produced fertile soils for millet and sorghum once iron tools spread.

Climatic oscillations demanded versatility, and Southern African societies learned to move, diversify, and store.

Societies and Political Developments

Forager Foundations and Pastoral Frontiers

At the dawn of this age, San and other forager bands occupied most of the subcontinent, moving between coastal shallows, mountains, and pans.

From the north, waves of Bantu-speaking agro-pastoralists entered through the Zambezi–Caprivi corridor, bringing ironworking, cereal cultivation, and livestock.

By the mid-first millennium CE, settled village clusters appeared along the Okavango’s backwaters and the Limpopo–Shashe drainage.

These farming and herding communities coexisted and traded with foragers, creating hybrid economies that fused new crops with ancient hunting knowledge.

Village Consolidation and Early Chiefdom Seeds

In the temperate interior, iron-age villages spread across the Highveld and southern Zimbabwe plateau, forming networks of kin-based hamlets that shared cattle enclosures and ancestral shrines.

Control of herds and exchange routes elevated some lineages into proto-chiefly status.

The southern Zimbabwe plateau — later the heart of Great Zimbabwe — already supported clustered settlements and localized craft specializations in pottery, smelting, and beadwork.

Meanwhile, mountain foragers of the Drakensberg and coastal groups along the Cape and Maputo basins maintained autonomy, adapting their subsistence to interaction with farming neighbors.

Economy and Trade

Across both subregions, mixed economies blended cultivation, herding, fishing, and foraging.

-

Tropical wetlands yielded sorghum, millet, yams, and floodplain vegetables; fish and waterfowl were dried for trade or storage.

-

Temperate plateaus produced grain, livestock, and iron goods.

-

Cattle and goats functioned as social capital and bridewealth, underpinning alliances.

Trade webs extended north to the Zambezi and east to the Indian Ocean:

copper, shells, and glass beads filtered southward; ivory, hides, and salt moved outward from the interior.

Though small in scale, these networks laid the infrastructure for later trans-Zambezi and Swahili-linked exchange.

Technology and Material Culture

The introduction of iron metallurgy after about 500 BCE transformed subsistence and craft.

Smelters produced hoes, knives, and spearheads; furnaces dotted the Limpopo and Okavango valleys.

Circular huts with thatch roofs clustered around cattle kraals; reed-walled dwellings rose on flood mounds in the Caprivi.

Basketry, bead-making, and pottery flourished — decorated with incised or combed motifs derived from central African prototypes.

Fishing weirs, dugout canoes, and stone traps along deltas and coasts reveal a sophisticated aquatic technology complementing herding and farming.

Belief and Symbolism

Spiritual life wove ancestral veneration with the older San trance traditions of transformation and rain-calling.

Villages honored lineage founders through hearth sacrifices and cattle offerings; foragers continued rock-painted rituals of the eland and rain animal.

Across the Okavango and Highveld, water and fertility spirits dominated oral myth, reflecting the ecological centrality of rainfall and flood.

Rock engravings near Etosha and the Limpopo recorded both hunting processions and cattle herding — visual testimony to the cultural convergence of forager and farmer cosmologies.

Adaptation and Resilience

Resilience rested on ecological mobility and diversification.

When drought struck the Highveld, families moved stock to riverine pastures; during floods, wetland dwellers retreated to mounds and stored grain in pottery jars.

Foragers supplemented village diets with game and honey; iron tools opened new agricultural margins.

Trade provided redundancy, moving salt, fish, and grain between arid and fertile zones.

The coexistence of mobile and sedentary lifeways insulated the region from collapse despite climatic swings.

Regional Synthesis and Long-Term Significance

By 819 CE, Southern Africa had matured into a dual ecological civilization:

-

In the tropical west, wetland fishers and herders of the Okavango–Caprivi sustained rich but dispersed communities attuned to water cycles.

-

In the temperate south, iron-farming chiefdoms and enduring forager enclaves created a dynamic cultural mosaic.

Together they formed the deep substrate for the southern Bantu world — mobile, inventive, and spiritually unified by reverence for ancestry and landscape.

Cattle paths, iron furnaces, and painted shelters were the era’s monuments: humble yet enduring signs of a region in transition from dispersed village economies to the monumental polities of the later first and early second millennia CE.

Groups

Topics

Commodoties

- Fish and game

- Weapons

- Hides and feathers

- Gem materials

- Glass

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Strategic metals

- Poisons