Upper East Asia (1252 – 1395 CE): …

Years: 1252 - 1395

Upper East Asia (1252 – 1395 CE):

Yuan–Ming Frontiers, Tibetan Lama–Patron Rule, and Moghulistan’s Rise

Geographic and Environmental Context

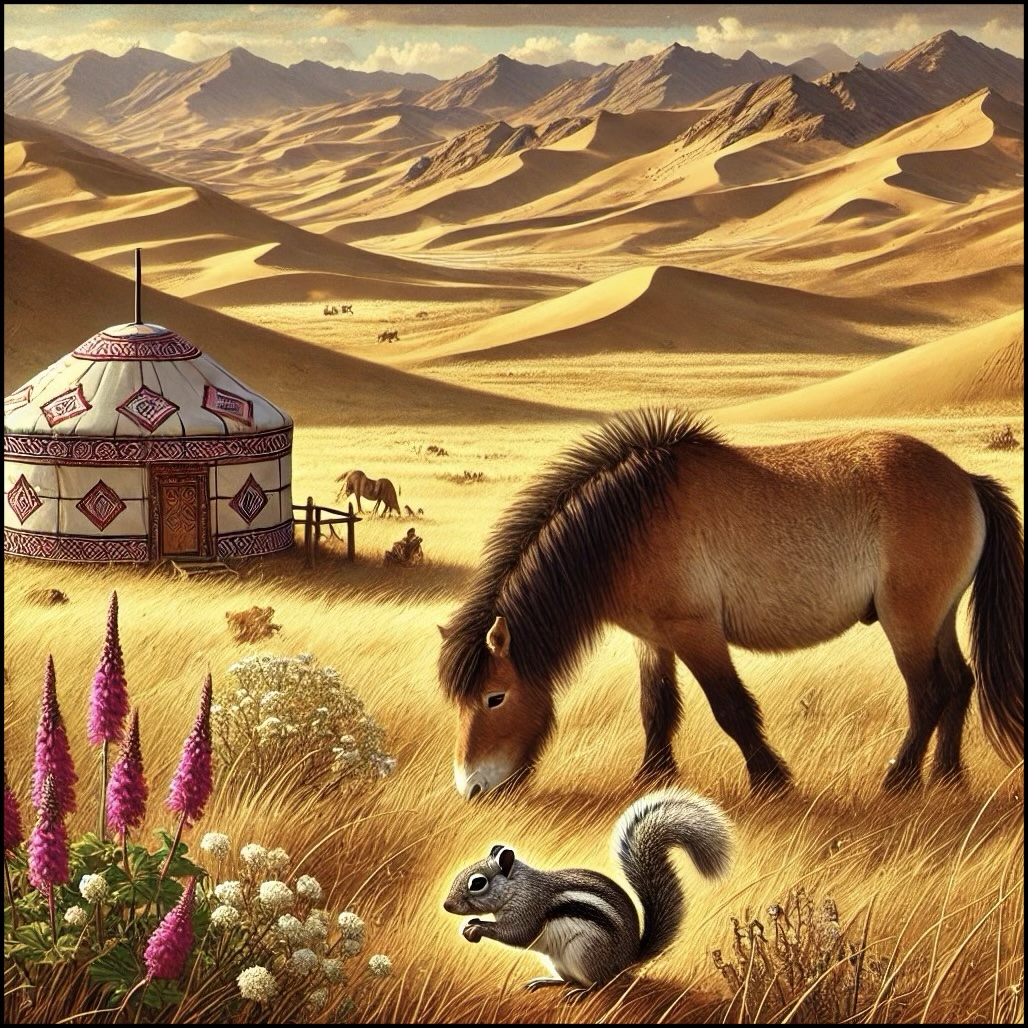

Upper East Asia spans Mongolia, Tibet, and China’s western highlands—Xinjiang, Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, and northwestern Sichuan—a mosaic of steppe/desert basins (Mongolia, Tarim, Qaidam), oasis arcs (Turfan–Hami, Dunhuang–Hexi), and high plateaus (Amdo–Ü–Tsang) bound by caravan and Tea–Horse roads.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

After c. 1300, cooler winters, some steppe drying, and episodic glacier advances marked the early Little Ice Age. Oases endured but were irrigation-sensitive; pastoralists widened seasonal ranges to hedge pasture shocks.

Societies and Political Developments

Mongolia (Yuan → Northern Yuan):

-

Under Yuan (1271–1368), Mongolia served as imperial pasture/military reserve.

-

After 1368 the court withdrew north; Northern Yuan formed on the steppe—Karakorum and eastern lineages contended with rising Oirat power late in the 14th century.

Xinjiang (Chagatai → Moghulistan):

-

The Chagatai ulus fractured; in the east, Moghulistan crystallized under Tughluq Temür (r. 1347–1363), promoting Islam among Turkic–Mongol elites.

-

Dughlat amirs dominated oases (Kashgar, Yarkand); Turfan/Hami oscillated between Yuan/Ming influence and steppe pressures.

Gansu–Ningxia–Hexi Corridor (Yuan → Ming):

-

A Yuan provincial spine (circuit offices, postal stations) linked Dadu to Central Asia via Dunhuang–Jiayuguan–Ganzhou.

-

With the Ming founding, frontier garrisons and beacon towers were restored, securing Hexi choke points.

Tibet (Ü–Tsang, Amdo, Kham):

-

Sakya hierarchs governed under the Yuan priest–patron framework; dpon-chen oversaw taxation and monastic estates.

-

From the 1350s, Phagmo Drupa leaders displaced Sakya in Ü–Tsang, inaugurating a Tibetan-led restoration; Tsongkhapa (b. 1357) began teachings that later grounded the Geluk school.

Northwestern Sichuan & Qinghai (Amdo):

-

Multiethnic buffer of Tibetan polities, Mongol banners, and Chinese prefectures; Yuan tusi institutions managed highland routes and pastures.

Economy and Trade

-

Caravan circuits: Hexi conveyed silk, tea, copper, ceramics west; eastbound trains brought horses, furs, musk, dyes, gems.

-

Tarim oases: (Kashgar–Yarkand–Khotan) exported cottons, felt, leather, jade; Turfan/Hami supplied raisins, silk, relay services.

-

Tea–Horse trade: Amdo–Kham–Sichuan routes swapped Chinese tea/cloth for Tibetan horses, salt, wool.

-

Pastoral staples: remounts, felt, hides exchanged for ironware and textiles. Chao facilitated long-distance exchange in the 13th–14th c.; bullion/barter re-emerged amid late-Yuan turmoil.

Subsistence and Technology

Irrigated oases (qanats, canals, walled gardens); high-valley barley/buckwheat; pastoral transhumance (horse–sheep–goat–camel–yak) and felt yurts. Gunpowder/siege tools in Yuan frontier forces; early Ming forts standardized beacon-rider relays along Hexi. Tibetan monastic estates ran granaries, bridges, and ferries, binding ritual authority to infrastructure.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Hexi trunk road: Dunhuang–Jiayuguan–Liangzhou–Ganzhou to the interior (postal yam relays).

-

Tarim rim road: Kashgar–Yarkand–Khotan–Cherchen–Dunhuang tied Moghulistan to China.

-

Tea–Horse roads (Chamagudao): Chengdu–Kangding–Chamdo–Lhasa (Amdo spurs).

-

Steppe arcs: Orkhon–Onon and Altai corridors linked Northern Yuan camps to Xinjiang thresholds.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Tibetan Buddhism: Sakya–Yuan lama–patron rule; post-1350 Phagmo Drupa revival; mountain/territorial cults (tsen).

-

Islam in Xinjiang: Moghulistan promoted Islamic law; oasis shrines and Sufi lineages grew.

-

Steppe cults & Buddhism: Northern Yuan upheld sky-ancestor rites while patronizing Tibetan Buddhism.

-

Chinese religiosity: Chan/Zen, Daoist cults, and popular rites persisted in frontier garrisons and towns.

Adaptation and Resilience

Layered authority (tusi, monastic estates, oasis begs, steppe khans) limited systemic collapse; route redundancy (Tarim vs. Hexi vs. Tea–Horse) kept traffic flowing; pastoral mobility buffered drought/snow calamities; institutional pivots (Ming frontier reform, Phagmo Drupa restoration, Moghulistan’s Islamic reorientation) stabilized borders.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395: Northern Yuan reconstituted steppe power; Moghulistan anchored an Islamic east-Chaghatai sphere; Phagmo Drupa restored Tibetan autonomy and monastic strength; Ming secured the Hexi gates and Tea–Horse exchanges—preserving Silk Road limbs and highland trades in horses, wool, tea, and jade.

Upper East Asia (with civilization) ©2024-25 Electric Prism, Inc. All rights reserved.

People

Groups

- Buddhism

- Buddhism, Tibetan

- Taoism

- Buddhists, Zen or Chán

- Tibetan people

- Oirats

- Mongols

- Mongol Empire

- Chagatai Khanate

- Tibet under Yuan rule

- Chinese Empire, Yüan, or Mongol, Dynasty

- Chagatai Khanate, Western

- Chinese Empire, Ming Dynasty

- Northern Yuan dynasty

Topics

Commodoties

- Weapons

- Hides and feathers

- Glass

- Colorants

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Fibers

- Textiles

- Ceramics

- Strategic metals

- Salt

- Aroma compounds

- Stimulants