Upper East Asia (1396–1539 CE): Ming Frontiers, …

Years: 1396 - 1539

Upper East Asia (1396–1539 CE): Ming Frontiers, Steppe Confederations, and Monastic Ascendancy

Geography & Environmental Context

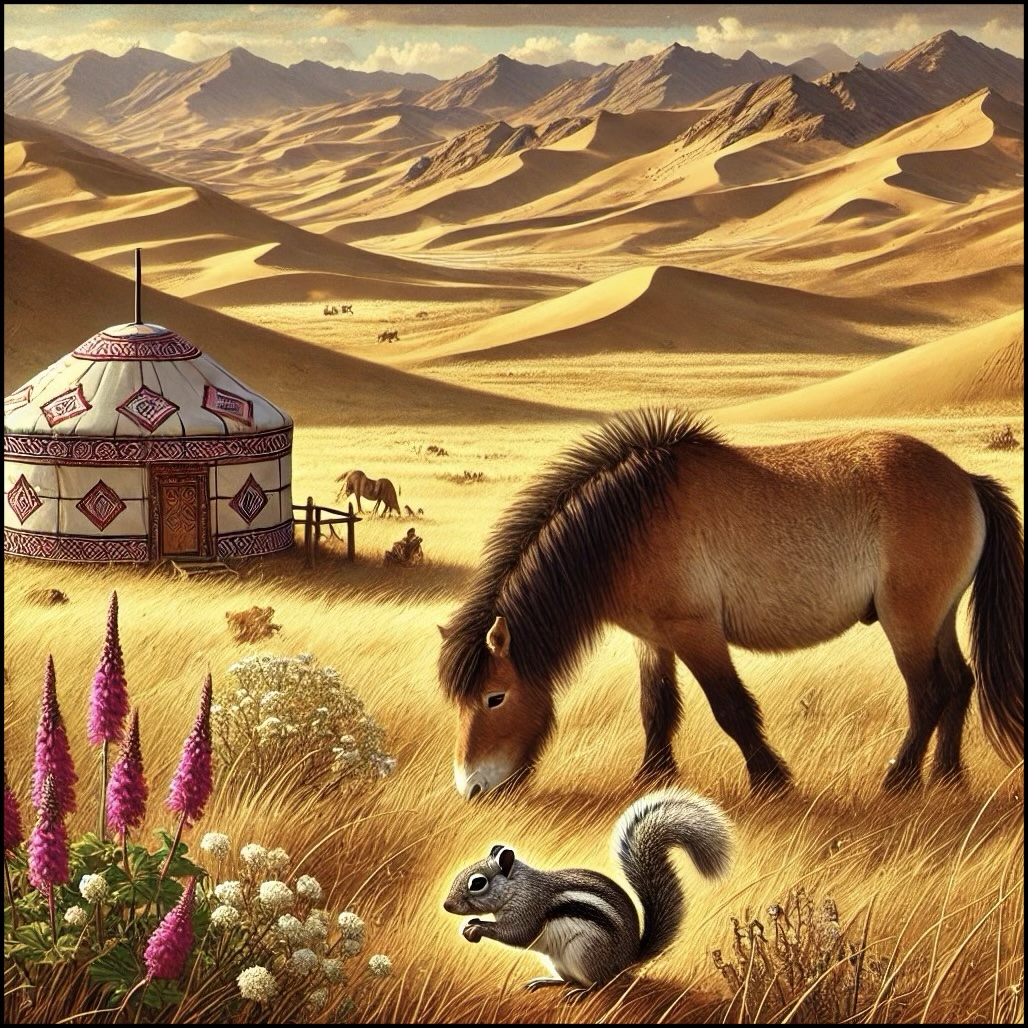

Upper East Asia spans Mongolia and western China: Tibet, Xinjiang, Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, northwestern Sichuan, northwestern Shaanxi, and northwestern Heilongjiang. Anchors include the Tibetan Plateau, the Taklamakan and Gobi Deserts, the Altai and Tianshan ranges, the Qinghai Lake basin, the Ordos Loop of the Yellow River, and the loess plateaus of Gansu and Shaanxi. This geography blends alpine pastures, desert basins, steppe grasslands, and irrigated valleys, creating a frontier between sedentary agrarian states and mobile pastoral worlds.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

During the Little Ice Age, winters grew harsher and droughts intensified. Steppe pastures contracted, forcing nomadic herders into sharper competition over grazing grounds. In the Tarim Basin, fluctuating rainfall stressed irrigation networks, while the Tibetan Plateau experienced shorter growing seasons but sustained productivity in barley fields. Flood and drought cycles along the Yellow River headwaters and Gansu corridor challenged farming communities, increasing pressure on imperial administrators.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Mongolia and Inner Mongolia: Pastoral nomadism dominated—herds of horses, sheep, goats, camels, and cattle provided subsistence, with gers (yurts) enabling mobility.

-

Xinjiang oases: Kashgar, Turpan, and Khotan maintained irrigated fields of wheat, barley, grapes, and melons.

-

Tibet and Qinghai: High-altitude barley farming and yak herding supported dense monastic estates.

-

Gansu and Ningxia: Han settlers cultivated millet, wheat, and beans, while Hui Muslim communities combined agriculture with caravan trade.

-

Northwestern Sichuan and Shaanxi: Loess terraces produced millet and wheat, blending Chinese agrarian traditions with frontier adaptations.

-

Northwestern Heilongjiang: Hunting and fishing by Evenki and Daur groups persisted, tied to fur and tribute exchanges.

Technology & Material Culture

Steppe technologies included saddles, stirrups, bows, and lances. Oasis farmers maintained qanat-like irrigation systems, while Tibetan monasteries expanded terracing and water channels. Architecture reflected cultural diversity: Buddhist monasteries in Tibet and Qinghai, Islamic mosques in Kashgar and Turpan, and Daoist and Confucian temples along the Gansu corridor. Trade goods included jade, salt, horses, furs, and Buddhist texts, exchanged for Chinese silk, porcelain, and tea.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Silk Road routes through Xinjiang and Gansu funneled caravans between China, Central Asia, and Persia.

-

Steppe highways linked Mongol clans across Inner and Outer Mongolia.

-

The Ming dynasty fortified the northern frontier with garrisons and walls, clashing with Mongol confederations.

-

In Tibet, monastic centers became both spiritual and economic hubs, connected by pilgrimage and caravan trails.

-

Islamic networks tied Xinjiang to Samarkand and Bukhara, carrying Sufi orders and merchants eastward.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Mongols: Political authority fragmented after the Yuan dynasty’s fall, but Chinggisid prestige remained powerful; epics and rituals celebrated clan ancestry.

-

Tibet: The rise of the Gelugpa school culminated in the growing prominence of the Dalai Lama, with monasteries like Drepung and Sera expanding.

-

Xinjiang oases: Islam shaped urban culture—mosques, madrasas, and shrines anchored community life.

-

Gansu and Ningxia: A mosaic of Han Chinese, Tibetan Buddhists, and Hui Muslims coexisted in market towns, their diversity visible in architecture and ritual practice.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Pastoralists diversified herds to buffer climatic shocks.

-

Oasis farmers relied on underground irrigation and grain storage.

-

Tibetan monasteries redistributed barley and butter during lean years.

-

Caravan trade served as a safety net, bringing grain and cloth into drought-stricken zones.

Transition

Between 1396 and 1539, Upper East Asia was defined by fragmentation and exchange. The Ming confronted resurgent Mongol confederations, while Tibetan monasteries consolidated power, and Islam deepened its hold on Xinjiang’s oases. Despite harsher climate, mobility, irrigation, and redistribution sustained resilience. The stage was set for the next period, when steppe confederations and expanding empires would redraw the balance of power.

Upper East Asia (with civilization) ©2024-25 Electric Prism, Inc. All rights reserved.

Groups

- Buddhism

- Buddhism, Tibetan

- Taoism

- Buddhists, Zen or Chán

- Tibetan people

- Oirats

- Mongols

- Mongol Empire

- Chagatai Khanate

- Tibet under Yuan rule

- Chinese Empire, Yüan, or Mongol, Dynasty

- Chagatai Khanate, Western

- Chinese Empire, Ming Dynasty

- Northern Yuan dynasty

Topics

Commodoties

- Weapons

- Hides and feathers

- Glass

- Colorants

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Fibers

- Textiles

- Ceramics

- Strategic metals

- Salt

- Aroma compounds

- Stimulants