Upper East Asia (1540–1683 CE): Steppe Revival, …

Years: 1540 - 1683

Upper East Asia (1540–1683 CE): Steppe Revival, Oirat Confederations, and the Shadow of Empire

Geography & Environmental Context

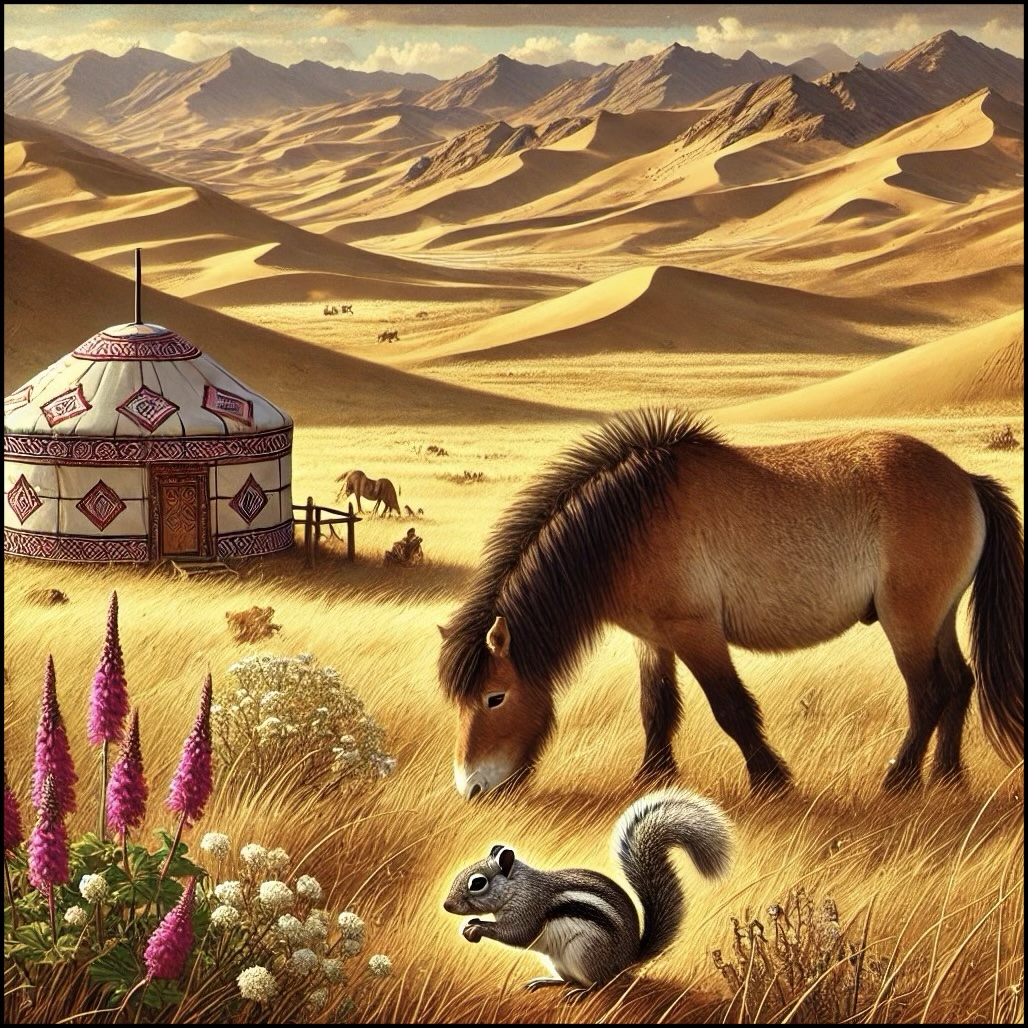

Upper East Asia encompasses Mongolia, Tibet, Xinjiang, Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, northwestern Sichuan, northwestern Shaanxi, and northwestern Heilongjiang. Anchors include the Altai and Tianshan mountains, the Gobi Desert, the Tibetan Plateau, the Taklamakan Basin, and the Yellow River headwaters in Qinghai and Gansu. Ecologies varied from alpine pastures and desert oases to loess farming valleys and steppe grasslands.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Little Ice Age reached one of its most severe phases. Steppe winters brought catastrophic dzud conditions, decimating herds. Drought cycles strained oasis agriculture in Turpan and Kashgar. Tibetan barley fields endured shorter summers. Floods in the Gansu corridor disrupted frontier farming. Ecological volatility heightened the stakes of political control and pushed nomads and farmers into closer competition for resources.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Mongolia: The rise of the Oirat confederation (later Zunghars) restored steppe political unity. Pastoral nomadism remained dominant, centered on horses and herds.

-

Xinjiang oases: Irrigated farming, viticulture, and caravan trade sustained cities like Kashgar, Yarkand, and Turpan.

-

Tibet and Qinghai: Monasteries continued as agrarian and spiritual hubs, redistributing barley and yak products.

-

Inner Mongolia, Gansu, Ningxia: Mixed farming and pastoralism supported hybrid frontier economies, with fortified Ming garrisons facing nomadic pressure.

-

Northwestern Sichuan and Shaanxi: Loess agriculture persisted, supporting military provisioning.

-

Northwestern Heilongjiang: Hunting and fishing cultures contributed furs to Qing and Russian tribute networks.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Steppe warfare: Horse-mounted archery remained crucial, supplemented by firearms acquired through Central Asian trade.

-

Oasis irrigation: Karez channels and canals maintained productivity despite drought.

-

Architecture: Tibetan monasteries expanded with Gelugpa patronage; Islamic madrasas and khan palaces flourished in Xinjiang; Ming frontier forts dotted Gansu and Inner Mongolia.

-

Trade goods: Horses, furs, and jade flowed outward; tea, silk, and porcelain moved inward; muskets and gunpowder weapons entered via Central Asia and Russia.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Oirat/Zunghar expansion: From the 1620s, the Zunghars dominated western Mongolia and Xinjiang, projecting power deep into Central Asia.

-

Silk Road routes: Oases linked Qinghai, Turpan, and Kashgar to Samarkand and Bukhara.

-

Tibet: The Fifth Dalai Lama consolidated authority with Mongol support, inaugurating a theocratic state in Lhasa.

-

Ming–Qing transition: As the Ming collapsed in the 1640s, the Manchus secured Inner Mongolia and expanded westward, preparing the ground for Qing control of the steppe.

-

Russian encroachment: Siberian expansion reached the Amur and Heilongjiang, sparking clashes with the Qing and shaping the Treaty of Nerchinsk (1689).

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Mongolia: Oirat/Zunghar elites patronized Tibetan Buddhism, using it to cement legitimacy; epics and genealogies reinforced steppe identity.

-

Tibet: The rise of the Dalai Lama’s authority created a fusion of monastic and political power, expressed through monumental building, ritual festivals, and thangka painting.

-

Xinjiang: Islam shaped daily life, with Sufi orders expanding influence; shrines and khan-led courts symbolized authority.

-

Frontier Gansu/Ningxia: Coexistence of Buddhist, Daoist, Muslim, and Confucian communities reflected cultural pluralism along caravan routes.

-

Northwestern Heilongjiang: Indigenous Evenki and Daur peoples maintained shamanic rites while entering into tribute relations with expanding empires.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Nomads diversified herds and moved seasonally to buffer against climate extremes.

-

Oasis farmers dug deeper irrigation channels and stored grain.

-

Tibetan monasteries provided famine relief through redistribution.

-

Ming and Qing granaries attempted to stabilize Gansu and Ningxia frontier populations.

-

Trade caravans distributed surpluses, linking steppe, plateau, and oases into a shared buffer system.

Transition

From 1540 to 1683, Upper East Asia was a crucible of steppe revival and imperial contest. The Oirat/Zunghars rose as a formidable power, Tibet emerged as a centralized monastic state, and Qing expansion absorbed Inner Mongolia while Russia pressed from the north. Climatic hardship intensified reliance on mobility, irrigation, and redistribution. By the end of this era, the stage was set for Qing conquest of Xinjiang and Tibet and the final eclipse of steppe independence in the 18th century.

Upper East Asia (with civilization) ©2024-25 Electric Prism, Inc. All rights reserved.

Groups

- Buddhism

- Buddhism, Tibetan

- Taoism

- Buddhists, Zen or Chán

- Tibetan people

- Oirats

- Mongols

- Mongol Empire

- Chagatai Khanate

- Tibet under Yuan rule

- Chinese Empire, Yüan, or Mongol, Dynasty

- Chagatai Khanate, Western

- Chinese Empire, Ming Dynasty

- Northern Yuan dynasty

Topics

Commodoties

- Weapons

- Hides and feathers

- Glass

- Colorants

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Fibers

- Textiles

- Ceramics

- Strategic metals

- Salt

- Aroma compounds

- Stimulants