Upper East Asia (1684–1827 CE): Steppe Confederations, …

Years: 1684 - 1827

Upper East Asia (1684–1827 CE): Steppe Confederations, Monastic States, and Qing Expansion

Geography & Environmental Context

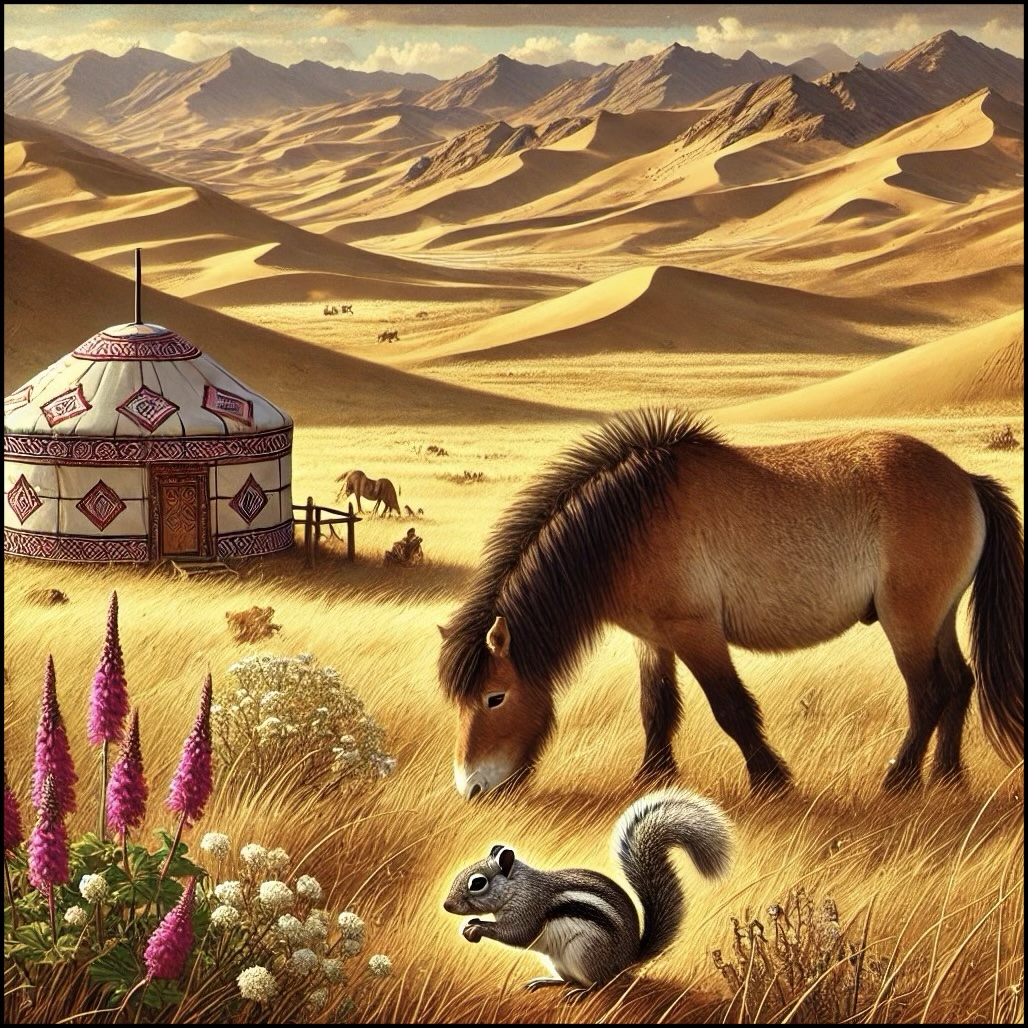

Upper East Asia encompasses Mongolia and western China: Tibet, Xinjiang, Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, northwestern Sichuan, northwestern Shaanxi, and northwestern Heilongjiang. Anchors include the Tibetan Plateau, the Taklamakan and Gobi Deserts, the Altai, Kunlun, and Tianshan ranges, the Qinghai Lake basin, the Ordos Loop of the Yellow River, and the forest-steppe of northern Heilongjiang. Landscapes ranged from alpine grasslands and desert basins to irrigated river valleys and loess plateaus, forming a frontier between nomadic and agrarian worlds.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The lingering Little Ice Age sharpened climate extremes. Steppe winters were bitter, with heavy livestock mortality during dzud (ice-crust winters), while prolonged droughts contracted pastures. In Xinjiang, shifting precipitation affected oasis irrigation. On the Tibetan Plateau, shortened growing seasons constrained barley harvests but glaciers fed rivers supporting valley communities. Gansu and Ningxia endured alternating droughts and floods, pressing frontier farmers. Despite hardship, ecological diversity across plateau, desert, and steppe allowed redistribution and survival.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Mongolia and Inner Mongolia: Nomadic pastoralism sustained herds of horses, sheep, goats, camels, and cattle. Portable gers (yurts) facilitated mobility between summer and winter pastures.

-

Xinjiang oases (Kashgar, Turpan, Hami, Khotan): Irrigated wheat, barley, melons, and grapes supported market towns and caravanserais along Silk Road corridors.

-

Tibet and Qinghai: Barley, yak herding, and salt extraction underpinned subsistence. Monasteries managed large estates and redistributed food during crises.

-

Gansu and Ningxia: Han settlers cultivated millet, wheat, and beans; Muslim Hui farmers combined agriculture with pastoralism.

-

Northwestern Sichuan and Shaanxi: Loess terraces and mixed agriculture linked Chinese heartland methods to frontier ecologies.

-

Northwestern Heilongjiang: Evenki, Daur, and Solon hunters combined reindeer, fishing, and pastoral practices, later incorporated into Qing tribute systems.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Pastoral tools: Saddles, stirrups, composite bows, lassos, and felt-making technologies remained central.

-

Agriculture: Oasis communities employed karez underground irrigation; Tibetan farmers used terrace and valley irrigation for barley.

-

Architecture: Monasteries like Drepung, Sera, and Tashilhunpo in Tibet, and mosques in Kashgar and Turpan, dominated skylines. Gansu featured Buddhist cave shrines and Confucian academies.

-

Trade goods: Horses, salt, furs, and jade flowed outward; tea, silk, and silver moved inward. Firearms and metal tools circulated via Russian, Central Asian, and Qing networks.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Steppe routes: Mongol herders traversed the Gobi, linking clans and khanates.

-

Silk Road oases: Kashgar, Turpan, and Hami facilitated exchange between Qing China, Central Asia, and Persia.

-

Qing frontier expansion: The Qing destroyed the Zunghar confederation in the 1750s, annexing Xinjiang. Garrisons, bannermen, and settlers followed, establishing new towns.

-

Tibet: After 1720, Qing suzerainty formalized through resident Ambans in Lhasa, though monasteries and the Dalai Lama retained spiritual authority.

-

Gansu and Ningxia corridor: A hinge zone where caravans, soldiers, and pilgrims moved between Central Asia, Tibet, and the Chinese heartland.

-

Russia: After Nerchinsk (1689) and Kiakhta (1727), regulated trade through caravans at Kyakhta tied Mongolia and northern Heilongjiang to Siberian markets.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Mongolia: Buddhism deepened its roots; monasteries became centers of literacy, economy, and authority. Horse festivals and epic tales preserved nomadic heritage.

-

Xinjiang: Islam dominated oasis towns; Sufi shrines and khan-led courts anchored spiritual and political life.

-

Tibet and Qinghai: Tibetan Buddhism flourished, producing monasteries, ritual dances, and thangka painting. Pilgrimages to Lhasa reinforced Tibetan identity.

-

Gansu and Ningxia: Cultural mosaics of Han, Hui, and Tibetan peoples expressed themselves in temples, mosques, and market rituals.

-

Northwestern Heilongjiang: Evenki and Daur shamanism persisted under Qing tribute and bannermen oversight.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Pastoral resilience: Herd diversification (horses, camels, yaks, sheep) cushioned ecological shocks.

-

Oasis ingenuity: Underground irrigation and storage stabilized food in drought-prone basins.

-

Monastic redistribution: Tibetan monasteries redistributed barley and butter, sustaining valley populations.

-

Trade relief: Caravans brought grain, tea, and textiles to famine-stricken zones.

-

Flexible settlement: Mobile gers, seasonal migrations, and multicropping minimized climate risk.

Transition

Between 1684 and 1827, Upper East Asia transformed under Qing imperial expansion. The destruction of the Zunghars shifted the balance of the steppe, while Tibet and Xinjiang were drawn into Qing structures through garrisons and tribute. Islam flourished in the oases, Tibetan Buddhism in the plateau, and Buddhism in Mongolia, even as Russian caravans introduced new goods and rival influences. Despite climatic hardship and political upheaval, the region’s societies adapted through mobility, irrigation, and ritual redistribution. By the early 19th century, Upper East Asia stood as a frontier zone of empire: incorporated into Qing sovereignty, yet culturally plural and resilient in its nomadic, Islamic, and Buddhist lifeways.

Upper East Asia (with civilization) ©2024-25 Electric Prism, Inc. All rights reserved.

Groups

- Buddhism

- Buddhism, Tibetan

- Taoism

- Buddhists, Zen or Chán

- Tibetan people

- Oirats

- Mongols

- Mongol Empire

- Chagatai Khanate

- Tibet under Yuan rule

- Chinese Empire, Yüan, or Mongol, Dynasty

- Chagatai Khanate, Western

- Chinese Empire, Ming Dynasty

- Northern Yuan dynasty

Topics

Commodoties

- Weapons

- Hides and feathers

- Glass

- Colorants

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Fibers

- Textiles

- Ceramics

- Strategic metals

- Salt

- Aroma compounds

- Stimulants