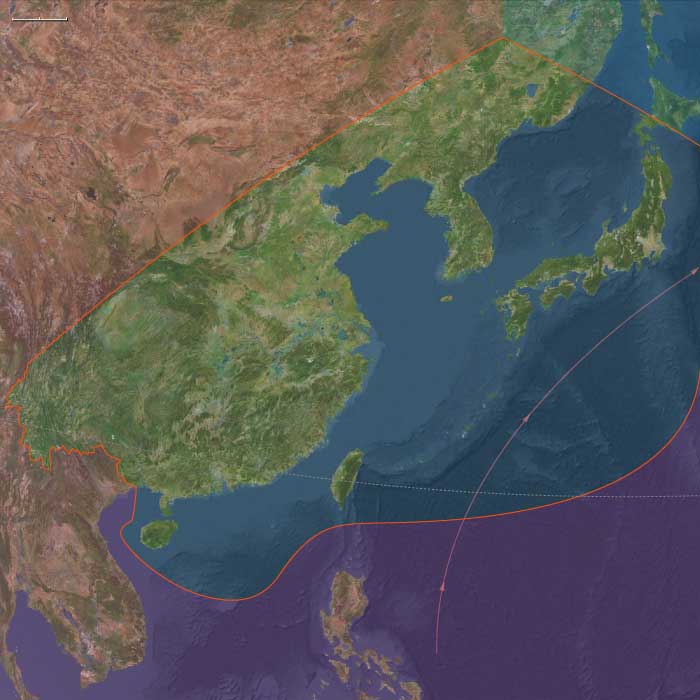

East Asia (1684 – 1827 CE) …

Years: 1684 - 1827

East Asia (1684 – 1827 CE)

Imperial Order, Maritime Gateways, and Frontiers of Faith and Steppe

Geography & Environmental Context

East Asia stretched from the Korean Peninsula and Japanese archipelago across the Chinese heartlands to the plateaus and deserts of Tibet and Xinjiang. Anchors included the Yellow and Yangtze River basins, the Sichuan Basin, Pearl River Delta, Loess Plateau, Tibetan Plateau, Tarim Basin, and Mongolian steppe. The region’s contrasts—fertile river plains, temperate coasts, and vast arid interiors—produced both dense agrarian states and mobile pastoral confederations.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Little Ice Age lingered, sharpening seasonal extremes: harsh northern winters, floods and droughts in the Chinese plains, and glacial-fed surpluses along Himalayan rivers. Typhoons ravaged southern coasts; volcanic eruptions such as Japan’s Mount Asama (1783) brought famine. Despite these stresses, adaptive irrigation, diversified crops (including maize and sweet potatoes from the Americas), and state granaries preserved food security on an unprecedented scale.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Agrarian Cores (China, Korea, Japan): Rice, wheat, and millet cultivation underpinned immense populations. In China, the Qing dynasty expanded irrigation and canal networks linking north and south; in Korea, Confucian landholding stabilized rural order; in Tokugawa Japan, agricultural intensification and market integration fueled urban growth in Edo, Osaka, and Kyoto.

-

Maritime and Island Zones: Taiwan’s rice and sugar plantations expanded under Han settlement; the Ryukyus prospered as diplomatic intermediaries between China and Japan.

-

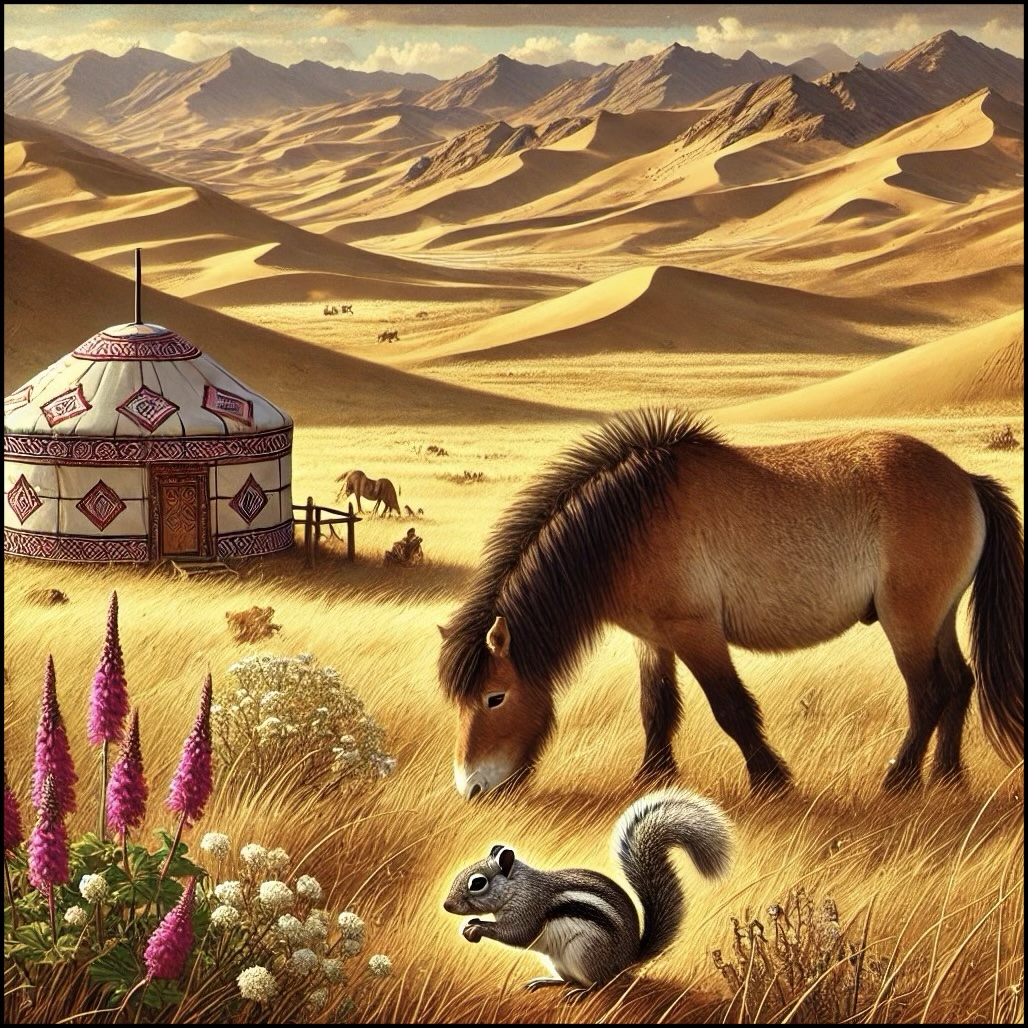

Frontier and Plateau Systems: Mongolia, Tibet, and Xinjiang sustained mobile herding, oasis farming, and monastic estates—ecologies attuned to altitude and aridity rather than monsoon rhythm.

By 1827 CE, East Asia’s population exceeded one-third of the world’s, supported by a lattice of irrigation, terraces, and transport corridors.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Agriculture & Engineering: Terracing, water-control works, and organic fertilization sustained high yields.

-

Manufacture & Trade: China’s silk, porcelain, and tea dominated global exports; Japan’s cotton, ceramics, and metalware supplied expanding domestic markets; Korean kilns and printing houses thrived under Joseon patronage.

-

Printing & Literacy: Movable type and woodblock presses diffused Confucian classics, vernacular novels, and technical treatises across the region.

-

Architecture & Urban Form: Confucian academies, Buddhist monasteries, Edo-period castles, and walled capitals embodied hierarchical harmony and aesthetic refinement.

-

Frontier Technologies: Tibetan monasteries refined metalwork and painting; oasis cities perfected karezirrigation and caravanserai architecture; steppe societies maintained horse tack, felt, and bow craftsmanship.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Continental Networks: The Silk Road persisted through Kashgar, Turpan, and Hami, funnelling jade, tea, and textiles between China and Central Asia.

-

Maritime Gateways: The Canton System (1757 onward) confined Western trade to Guangzhou, channeling American silver for Chinese tea and porcelain. Dejima in Nagasaki remained Japan’s controlled European portal; Ryukyuan and Korean embassies linked Edo, Beijing, and Seoul.

-

Imperial Integration: The Qing conquest of Tibet and Xinjiang established garrisons and ambans; Russian treaties at Nerchinsk (1689) and Kiakhta (1727) opened regulated frontier trade.

-

Pilgrimage and Learning: Tibetan, Mongol, and Chinese monks traveled between Lhasa and Beijing; scholars from Korea and Japan circulated Confucian texts and practical science within tributary circuits.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

China: The Qing literary renaissance blended classical scholarship with popular creativity—Dream of the Red Chamber epitomized its depth. Temple networks to Mazu and local deities reinforced maritime identity.

-

Korea: The yangban elite curated Confucian orthodoxy while pansori storytelling and mask drama voiced common life.

-

Japan: The Edo “Floating World”—ukiyo-e prints, kabuki, haiku, and tea culture—expressed disciplined exuberance within order.

-

Tibet & Mongolia: Buddhist monasteries functioned as spiritual, economic, and artistic centers; epic poetry and masked dance celebrated cosmic kingship.

-

Xinjiang: Islamic courts and Sufi lodges blended Persianate and Turkic traditions, sustaining rich manuscript and shrine cultures.

Together these traditions forged one of history’s most literate and artistically dynamic macro-regions.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Hydraulic Infrastructure: Massive flood-control embankments on the Yellow River and canal dredging across the Yangtze basin moderated famine risk.

-

Crop Diversification: Maize, potatoes, and peanuts mitigated rice dependency.

-

Forestry & Fishery Regulation: Tokugawa Japan’s conservation edicts and China’s fish-pond–mulberry integration balanced extraction and renewal.

-

Frontier Mobility: Steppe herding cycles and oasis trade redistributed resources across ecological zones.

-

Monastic Relief: Tibetan and Chinese religious estates operated granaries and soup kitchens during dearth.

Political & Military Shocks

-

Qing Expansion: Conquest of the Zunghars (1755–57) annihilated the last major steppe rival, extending imperial rule to Central Asia and Tibet.

-

Domestic Administration: The Qing consolidated the Eight Banner system and civil-service exams; famine relief and censorship systems exemplified bureaucratic reach.

-

Korean Continuity: The Joseon dynasty upheld Confucian governance and tributary diplomacy.

-

Tokugawa Peace: The shogunate’s sakoku policy maintained 250 years of internal peace and cultural growth but limited foreign exchange.

-

Maritime Pressures: European traders and missionaries—confined to specific ports—tested Asian gatekeeping; Russian advance across Siberia introduced a new northern frontier dynamic.

Transition

From 1684 to 1827 CE, East Asia stood as the world’s largest and most stable macro-civilization: agrarian wealth, bureaucratic precision, and artistic refinement coexisted with dynamic frontiers and selective global contact. The Qing Empire ruled from Beijing to Lhasa; Tokugawa Japan perfected isolation amid prosperity; Joseon Korea cultivated moral governance; Tibet, Mongolia, and Xinjiangmaintained spiritual and ethnic autonomy within empire.

By the early nineteenth century, prosperity concealed mounting strain—population pressure, silver dependence, and the probing of Western trade empires. Yet the region’s cohesion, intellectual vigor, and ecological balance left it poised to meet the convulsions of the coming century not as a passive periphery, but as a self-confident center of the early modern world.

Upper East Asia (with civilization) ©2024-25 Electric Prism, Inc. All rights reserved.

Groups

- Buddhism

- Buddhism, Tibetan

- Taoism

- Buddhists, Zen or Chán

- Tibetan people

- Oirats

- Mongols

- Mongol Empire

- Chagatai Khanate

- Tibet under Yuan rule

- Chinese Empire, Yüan, or Mongol, Dynasty

- Chagatai Khanate, Western

- Chinese Empire, Ming Dynasty

- Northern Yuan dynasty

Topics

Commodoties

- Weapons

- Hides and feathers

- Glass

- Colorants

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Fibers

- Textiles

- Ceramics

- Strategic metals

- Salt

- Aroma compounds

- Stimulants