Western Southeast Europe (820 – 963 CE): …

Years: 820 - 963

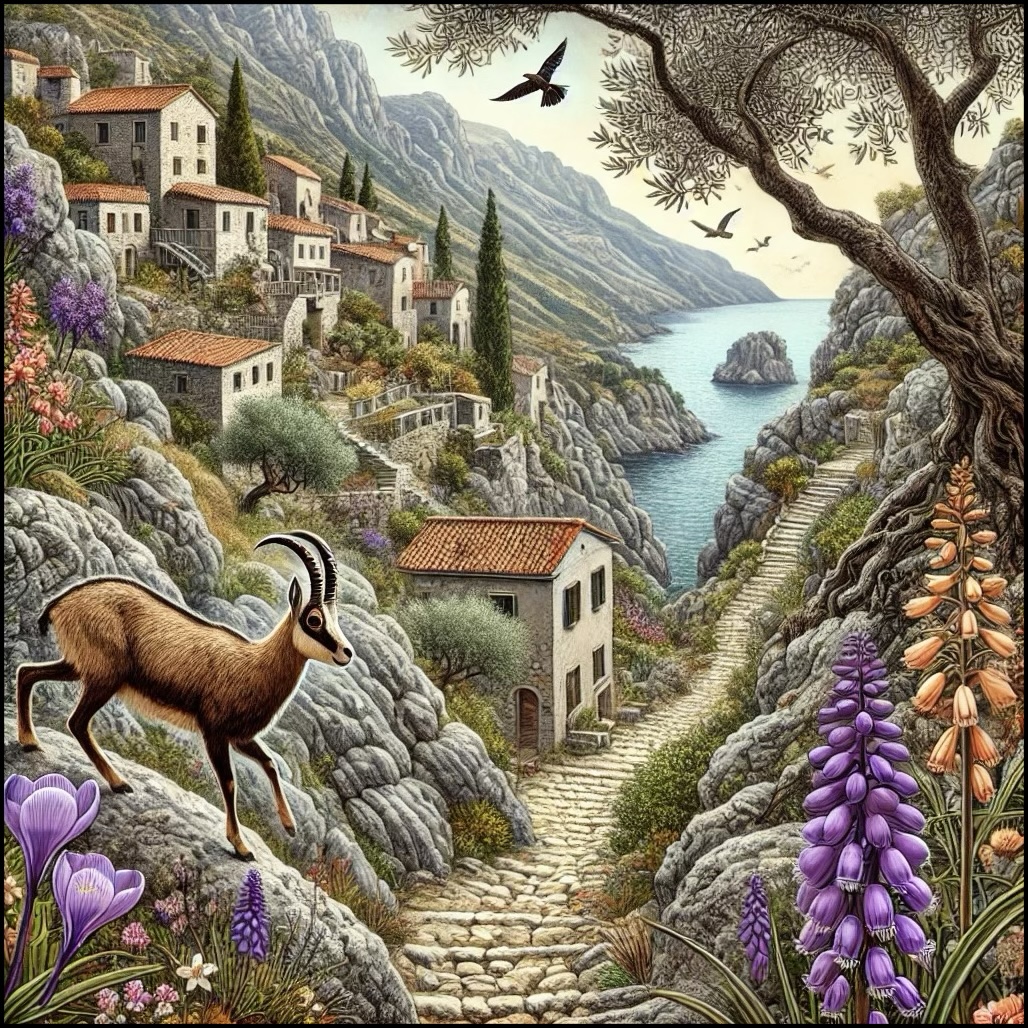

Western Southeast Europe (820 – 963 CE): Byzantine Greece, Slavic Principalities, and the Adriatic City-Ports

Geographic and Environmental Context

Western Southeast Europe includes Greece (outside Thrace), Albania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Kosovo, most of Bosnia, southwestern Serbia, most of Croatia, and Slovenia.

-

Coastal lowlands and islands along the Adriatic (Dalmatia, the Ionian isles) met the Dinaric and Pindus mountains’ karst and upland pastures.

-

Interior corridors—Morava–Vardar, Drina–Sava, and the Via Egnatia from Dyrrachium (Durres) to Thessaloniki—linked the Aegean and Adriatic to the central Balkans.

-

River valleys and Mediterranean basins of Attica, Boeotia, Peloponnese, and Epiros anchored Byzantine agrarian themes.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

A Mediterranean–continental mix: wet winters and dry summers on the coasts; cooler, more variable regimes inland.

-

Toward the 10th century, the onset of the Medieval Warm Period slightly lengthened growing seasons, aiding vine and olive culture in Greece and mixed cereal–pastoral economies inland.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Byzantine Greece:

-

The empire reasserted control over earlier Slavic settlements (Sklaviniai) in Hellas and the Peloponnese, strengthening the Themes of Hellas and Peloponnēsos.

-

Under Basil I (867–886) and Leo VI (886–912), fort networks and fiscal-military administration recovered towns; Constantine VII (r. 913–959) codified provincial governance.

-

Monastic revival culminated at the end of the age with St. Athanasios founding the Great Lavra (963) on Mount Athos, inaugurating the Athonite commonwealth.

-

-

Dalmatian coast & Adriatic cities (Split, Zadar, Trogir, Ragusa/Dubrovnik):

-

Urban municipalities under Byzantine suzerainty (with Latin civic traditions) acted as maritime hubs between Venice, southern Italy, and the Aegean; local comites and councils balanced imperial interests and city autonomy.

-

-

Croatia:

-

The Duchy of Croatia consolidated in the 9th century; Christianity advanced under Frankish and papal influence.

-

Tomislav (traditionally crowned c. 925) forged a Kingdom of Croatia, mediating between Byzantium (Dalmatian cities) and the interior.

-

Glagolitic liturgy (from the missions of Cyril and Methodius) took root alongside the Latin rite.

-

-

Serbian lands (Raška, Zahumlje, Travunija, Duklja/Dioclea):

-

The Vlastimirović dynasty (Serbia/Raška) and coastal principalities in Zahumlje (Herzegovina), Travunija, and Duklja (Montenegro) navigated between Byzantine, Bulgar, and later Croatian pressures.

-

Baptism and church-building progressed unevenly; župans governed district polities (župe) from hillforts (gradine).

-

-

Bosnia & inland Slovenia:

-

Clustered hillfort communities under local župans and counts emerged along the Drina–Bosna–Vrbas and Sava corridors, tied to Croatian and Frankish spheres.

-

-

North Macedonia & Kosovo:

-

Slavic communities in Macedonia and the Vardar basin faced alternating Byzantine and Bulgar influence; Thessaloniki remained the imperial anchor in the region.

-

The cultural afterglow of the Cyril–Methodius mission (863) radiated west via disciples and scriptoria.

-

Economy and Trade

-

Agriculture:

-

Greece—olives, vines, wheat, and garden crops under village commons and monastic estates.

-

Uplands—transhumant flocks; lowlands—cereal rotations; coastal lagoons—salt and fish.

-

-

Trade:

-

Via Egnatia moved Balkan grain, timber, and wax from Dyrrachium to Thessaloniki and Constantinople.

-

Adriatic shipping linked Dalmatian cities to Venice and Apulia; Byzantine nomismata and Italian denarii circulated with cloth, wine, ceramics, and metalware.

-

Interior market nodes (e.g., Skopje, Niš) exchanged hides, honey, wax, and slaves for Mediterranean goods.

-

Subsistence and Technology

-

Terrace agriculture in Greek highlands; irrigation channels and cisterns in lowland plains.

-

Pastoral transhumance across Dinaric and Pindus slopes; wool and hides fed urban workshops.

-

Ship types: Byzantine dromōn and coastal transports; Dalmatian galleys and coasters; standardized amphorae and barrels for wine/oil.

-

Fortifications: stone kastra along roads and passes; timber–earth hillforts (gradine) in inland Slavic zones.

-

Scripts: Latin in the Adriatic cities; Greek in Byzantine administration; Glagolitic (later Cyrillic) permeated Slavic ecclesiastical use.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Via Egnatia: Dyrrachium–Thessaloniki–Constantinople, the main imperial artery.

-

Morava–Vardar corridor: interior route from the middle Danube to the Aegean.

-

Adriatic sea-lanes: Venice ⇄ Dalmatia ⇄ Greece; island chains served as stepping-stones.

-

Mountain passes (e.g., Katara, Metsovo, Ivan): controlled troop movement and caravan traffic.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Orthodox Christianity dominated Byzantine Greece; icons, relic cults, and monastic patronage shaped sacred geography (Athos, Meteora precursors).

-

Latin Christianity prevailed in Dalmatian municipalities and among Croatian elites; rivalry and cooperation with Byzantium coexisted.

-

Slavic Christianization advanced via Cyril–Methodius’ Slavic liturgy and local bishoprics; pagan survivals persisted in upland communities.

-

Crosses on hillforts, basilicas in towns, and rural shrines marked the Christianization landscape.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Theme (provincial) systems mobilized local troops and taxes, enabling Byzantine Greece to weather raids and recover lands.

-

Maritime redundancy—Adriatic and Aegean lanes—kept trade moving when inland conflict flared.

-

Dual rites—Latin and Greek—reduced friction at the Adriatic–Aegean interface by embedding diplomacy in liturgy.

-

Hillfort + kastron pairing allowed interior polities to buffer against Bulgar pushes and raiding.

Long-Term Significance

By 963 CE, Western Southeast Europe was a braided frontier:

-

Byzantine Greece reestablished provincial depth and spiritual authority (Athos at the close of the age).

-

Croatia crystallized into a kingdom, mediating Adriatic and inland interests.

-

Serbian principalities and Macedonian Slavs balanced between Bulgaria and Byzantium.

-

Dalmatian cities prospered as Adriatic brokers under imperial suzerainty.

These dynamics set the stage for the Bulgar–Byzantine wars of the next age, the Adriatic rise of Venice, and the maturation of Slavic Christian polities across the western Balkans.

Western Southeast Europe (with civilization) ©2024-25 Electric Prism, Inc. All rights reserved.

People

- Athanasius the Athonite

- Basil I

- Constantine VII

- Leo VI the Wise

- Saints Cyril and Methodius

- Tomislav of Croatia

Groups

- Slavs, South

- Christianity, Chalcedonian

- Greeks, Medieval (Byzantines)

- Bulgarian Empire (First)

- Bulgarians (South Slavs)

- Hellas, Theme of

- Venice, Duchy of

- Serbian Principality

- Macedonia, East Roman Theme of

- Croatia (Pannonian), Principality of

- Croatia (Dalmatian, or Littoral), Principality of

- Peloponnese (theme)

- Roman Empire, Eastern: Non-dynastic

- Croats (South Slavs)

- Serbs (South Slavs)

- Roman Empire, Eastern: Phrygian or Armorian dynasty

- Travunia

- Roman Empire, Eastern: Macedonian dynasty

- Bulgarian Orthodox Church

- Bulgarian Empire (First)

- Croatia, Kingdom of

- Duklja, or Doclea

Topics

Commodoties

- Glass

- Domestic animals

- Oils, gums, resins, and waxes

- Grains and produce

- Textiles

- Ceramics

- Strategic metals

- Salt

- Beer, wine, and spirits

- Manufactured goods

- Money

- Aroma compounds