Louis-Antoine de Bougainville

French admiral and explorer

Years: 1729 - 1811

Louis-Antoine, Comte de Bougainville (12 November 1729 – 31 August 1811) is a French admiral and explorer.

A contemporary of James Cook, he takes part in the French and Indian War and the unsuccessful French attempt to defend Canada from Britain.

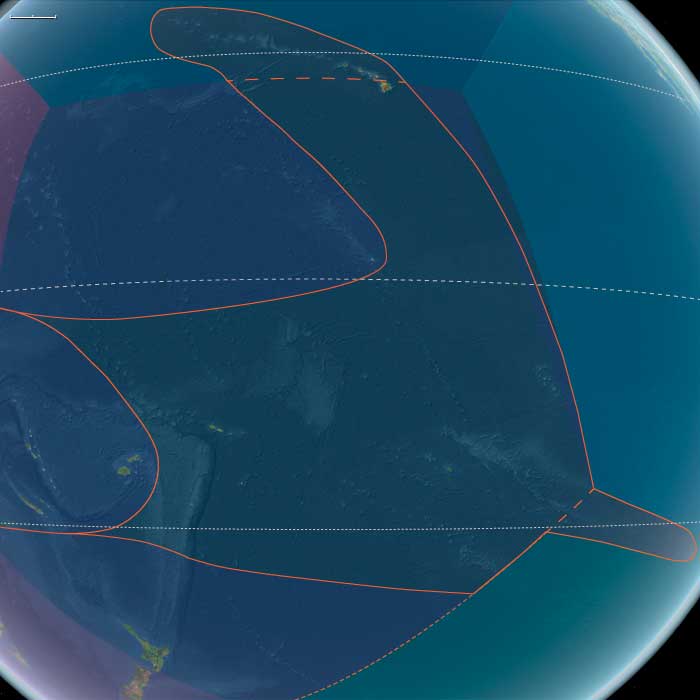

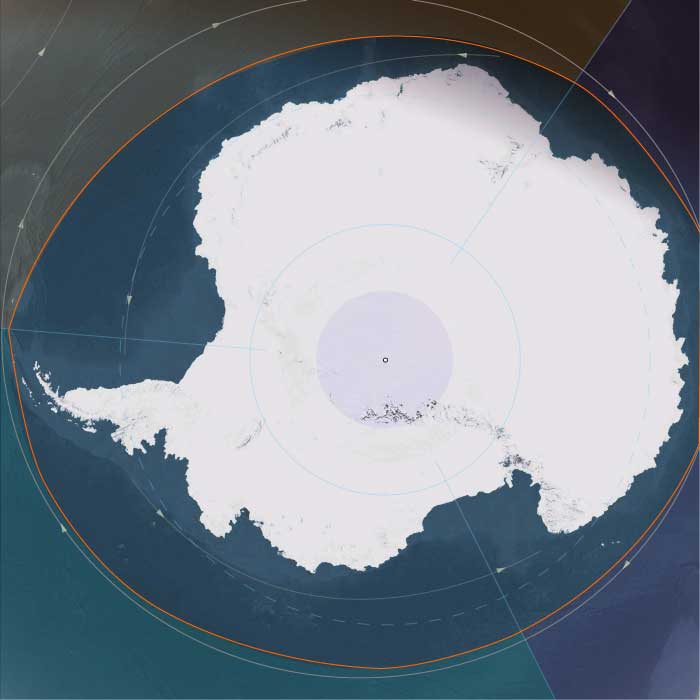

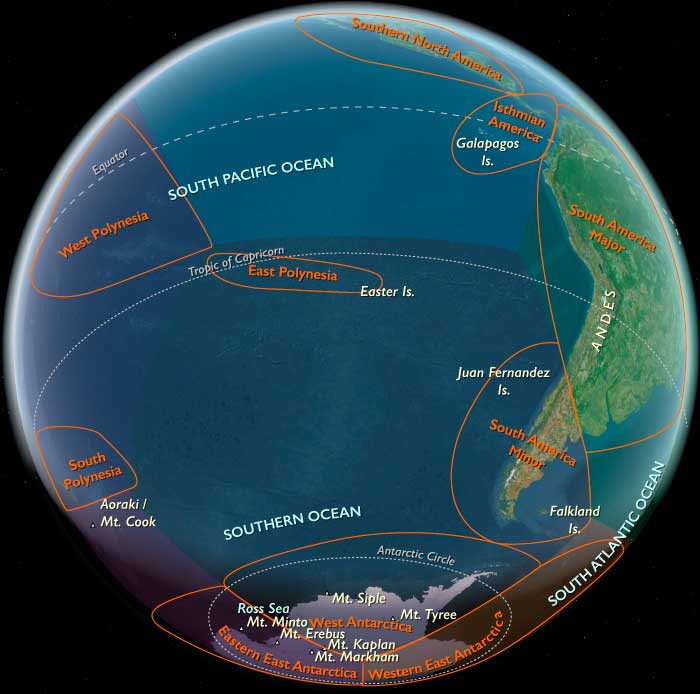

He later gains fame for his expeditions to settle the Falkland Islands and his voyages into the Pacific Ocean.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 57 total

French explorers, such as Bougainville and Lapérouse, take part in the voyages of scientific exploration through maritime expeditions around the globe.

The Enlightenment philosophy, in which reason is advocated as the primary source for legitimacy and authority, undermines the power of and support for the monarchy and helps pave the way for the French Revolution.

English sailors had first sighted the Falklands in the late sixteenth century.

The government had made a halfhearted claim in the following century, although under the Treaty of Tordesillas they fall within the Spanish orbit.

London had only begun to give the matter its serious attention in 1748, with the report of Admiral Lord Anson, sounding out the Spanish on the question of sovereignty.

This had only had the effect of drawing up the battle lines, though the matter was put to one side for the time being.

An uncertain equilibrium might have remained but for the unexpected intervention of a third party, France.

France establishes a colony at Port St. Louis, on East Falkland's Berkeley Sound coast in 1764.

The French name Îles Malouinesis given to the islands—malouin being the adjective for the Breton port of Saint-Malo.

The Spanish name Islas Malvinas is a translation of the French name.

In 1766, France agrees to leave, and Spain agrees to reimburse Louis de Bougainville, who has established a settlement at his own expense.

The Spaniards assume control in 1767 and rename Port St. Louis as Puerto Soledad.

The British, who have fewer native allies, have resort to companies of rangers for their scouting and reconnaissance activities.

The ranger companies, organized and directed by Robert Rogers, had eventually became known as Rogers' Rangers.

In the winter of 1757, Rogers and several companies of his rangers are stationed at Fort William Henry at the southern end of Lake George and at Fort Edward on the upper Hudson.

These forts are principally garrisoned by elements of the 44th and 48th Regiments, and form the frontier between the British province of New York and the French province of Canada.

Captain Rogers had led a scouting expedition from Fort Edward on January 15, stopping at Fort William Henry to acquire provisions, snowshoes, and additional soldiers.

The company had left Fort William Henry on January 17 with eighty-six men, heading down the frozen Lake George.

The next day, twelve men had turned back because of injuries.

The remaining men had continued north, ...

After spotting a sled moving on the lake toward Fort St. Frédéric, Rogers sends Lieutenant John Stark and some men to intercept it.

However, more sleds are spotted, and Stark's men are seen before they can retreat back into the woods.

The sleds turned back toward Carillon.

The British give chase, but most of the French escape.

Rogers succeeds in taking seven prisoners.

Rogers' men now walk into an ambush, according to his estimate, by "two hundred and fifty French and Indians."

The British were fortunate that many of the French muskets misfire due to wet gunpowder, as the surprise is nearly complete.

Lieutenant Stark, who is bringing up the rear of the ranger column, establishes a defensive line on a rise with some of his men, from which they give covering fire as those in the front retreat to this position.

As they retreat, Rogers orders his captives slain so that his men might move more freely.

The fight lasts several hours and ends only after sunset, when neither side can see the other.

Rogers is injured twice during the battle, once to the head and once to the hand.

The French will report that they were at a disadvantage, since they were without snowshoes and in snow up to their knees.

Once darkness sets in, Rogers and his survivors retreat six miles (nine point seven kilometers) to Lake George, where he sends Stark with two men to Fort William Henry for assistance.

Other captured British end up as slaves to the natives.

Thomas Brown, who will publish a pamphlet that vividly describes his captivity, will spend almost two years in slavery, traveling as far as the Mississippi River before reaching Albany in November 1758.

Bougainville was born in Paris, the son of a notary, on either November 11 or 12, 1729.

In early life, he had studied law, but soon abandoned the profession.

In 1753 he had entered the army in the corps of musketeers.

At the age of twenty-five he had published a treatise on integral calculus, as a supplement to De l'Hôpital's treatise, Des infiniment petits.

He had been sent in 1755 to London as secretary to the French embassy, where he was made a member of the Royal Society.

Stationed in Canada in 1756 as captain of dragoons and aide-de-camp to the Marquis de Montcalm,

Bougainville had taken an active part in the capture of Fort Oswego in 1756.

A similar battle will be fought the following year, in which Rogers will very nearly be killed and his company decimated.

Its walls are thirty feet (nine point one meters) thick, with log facings surrounding an earthen filling.

Inside the fort are wooden barracks two stories high, built around the parade ground.

Its magazine is in the northeast bastion, and its hospital is located in the southeast bastion.

The fort is surrounded on three sides by a dry moat, with the fourth side sloping down to the lake.

The only access to the fort is by a bridge across the moat.

The fort is capable of housing only four to five hundred men; additional troops are quartered in an entrenched camp seven hundred and fifty yards (six hundred and ninety meters) southeast of the fort, near the site of the 1755 Battle of Lake George.

Fort William Henry had been garrisoned during the winter of 1756–57 by several hundred men from the 44th Foot under Major Will Eyre.

In March 1757 the French send an army of fifteen hundred to attack the fort under the command of the governor's brother, François-Pierre de Rigaud.

Composed primarily of colonial troupes de la marine, militia, and natives, and without heavy weapons, they besiege the fort for four days.

Lacking sufficient logistical and artillery support, and hampered further by a blinding snowstorm on 21 March, French forces are unable to take the fort and the siege is called off.

Although the French fail to take the fort itself, their forces do destroy three hundred bateaux and several lightly armed vessels beached on the shore, a saw-mill and numerous outbuildings before retreating.

Submitted to the government in London in September 1756, the plan calls for a purely defensive posture along the frontier with New France, including the contested corridor of the Hudson River and Lake Champlain between Albany, New York and Montreal.

Following the Battle of Lake George in 1755, the French had begun construction of Fort Carillon (now known as Fort Ticonderoga) near the southern end of Lake Champlain, while the British had built Fort William Henry at the southern end of Lake George, and Fort Edward on the Hudson River, about sixteen miles (twenty-six kilometers) south of Fort William Henry.

The area between William Henry and Carillon is a wilderness dominated by Lake George.

Loudoun's plan depends on the expedition's timely arrival at Quebec, so that French troops will not have the opportunity to move against targets on the frontier, and will instead be needed to defend the heartland of the province of Canada along the Saint Lawrence River.

However, political turmoil in London over the progress of the Seven Years' War both in North America and in Europe has resulted in a change of power, with William Pitt the Elder rising to take control over military matters.

Loudoun consequently does not receive any feedback from London on his proposed campaign until March 1757.

Before this feedback arrived he had developed plans for the expedition to Quebec, and had worked with the provincial governors of the Thirteen Colonies to develop plans for a coordinated defense of the frontier, including the allotment of militia quotas to each province.

When William Pitt's instructions finally reach Loudoun in March 1757, they call for the expedition to first target Louisbourg on the Atlantic coast of Île Royale, now known as Cape Breton Island.

Although this does not materially affect the planning of the expedition, it is to have significant consequences on the frontier.

The French forces on the Saint Lawrence will be too far from Louisbourg to support it, and will consequently be free to act elsewhere.

Loudoun assigns his best troops to the Louisbourg expedition, and places Brigadier General Daniel Webb in command of the New York frontier.

He is given about two thousand regulars, primarily from the 35th and 60th (Royal American) Regiments.

The provinces are to supply Webb with about five thousand militia.

Monro establishes his headquarters in the entrenched camp, where most of his men are located.

The French may have not been able to take the fort, but the destruction of so many boats crippled Monro’s ability to sortie reconnaissance parties further up the lake to assess French and native movements.

The loss of the boats and manpower shortages make patrolling and scouting outside the protective walls of Fort William Henry precarious for Monro and he is unable to send out sufficient scouts.

Monro can do little to respond to the native raids or gain intelligence on French movements until sufficient reinforcements arrive.

He also moves slowly to re-construct the buildings and boats destroyed by the French months earlier.

Reinforcements finally arrive in June when Provincial and militia units from New York, New Jersey and New Hampshire are sent up from Fort Edward by General Daniel Webb.

Desperate for information and now newly reinforced, Monro decides to act.