Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 253 total

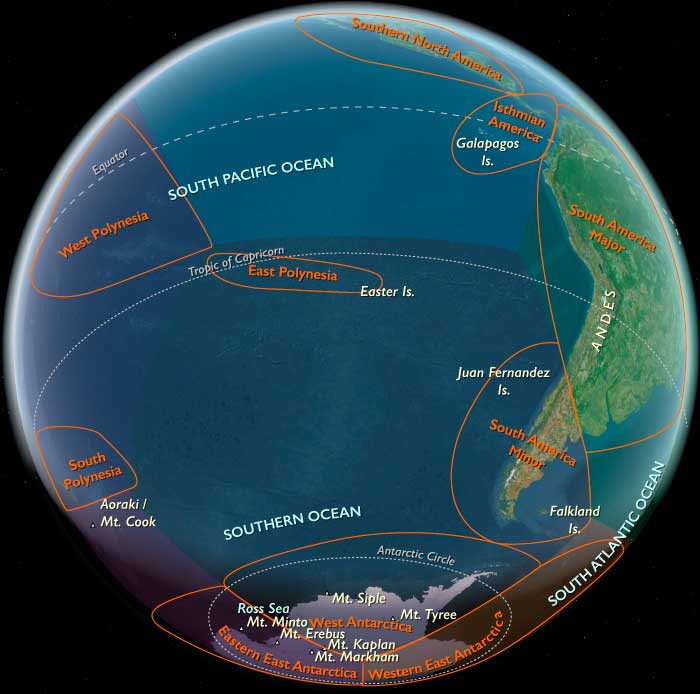

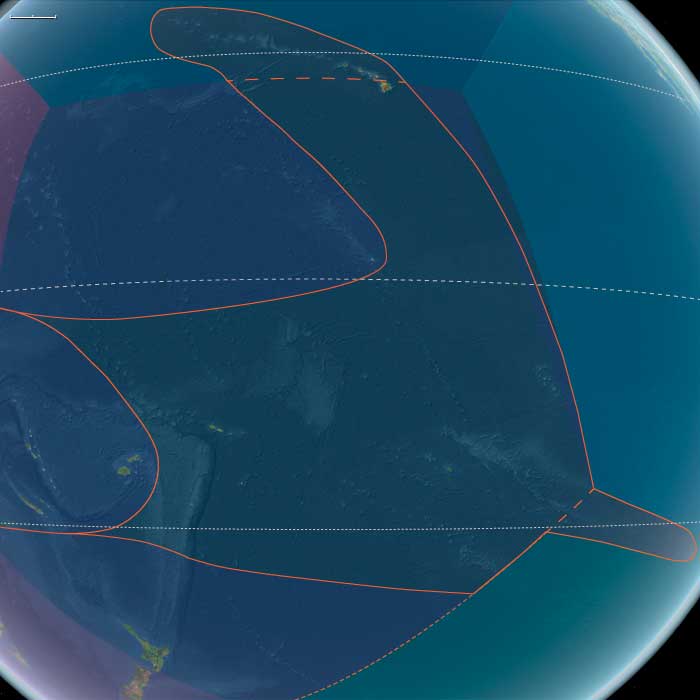

Polynesia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Paleolithic I — Volcanic Arcs, Reef Foundations, and the Architecture of Isolation

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the later Pleistocene, the Polynesian sector of the Pacific was a scattered domain of volcanic peaks, emerging atolls, and widening reef flats—a geography still entirely devoid of humans but already constructing the natural architecture that would one day sustain them.

The region spanned three great arcs of islands:

-

The Hawaiian–Emperor chain in the north, including Oʻahu, Maui, Molokaʻi, Kauaʻi, Niʻihau, and Midway, where high volcanic forms dominated the subtropics.

-

The central–western archipelagos—Tonga, Samoa, the Cook and Society Islands, the Marquesas, Tuvalu, and Tokelau—a mixture of high volcanic islands, raised limestone platforms, and embryonic atolls.

-

The eastern fringe—future Pitcairn and Rapa Nui—where lone volcanic edifices rose from deep ocean basins, linked only by the great South Pacific gyres and currents.

Sea level stood ~100 m lower than today, exposing vast coastal benches and broad shelves around high islands. Many modern lagoons lay dry, their reef rims fossilized in the air; others built episodically with interglacial warm phases. Across the region, reef, volcano, and ocean interacted in long cycles of uplift and subsidence—the slow choreography that would, over tens of millennia, produce the Polynesian Triangle’s intricate geography.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The epoch was framed by full glacial conditions—cooler sea-surface temperatures, stronger trade winds, and a sharply defined dry season.

-

Atmosphere and Ocean: Strengthened trades drove upwelling along many leeward coasts, favoring cool, nutrient-rich nearshore waters. Seasonal dust episodes and winter surf reworked coastal benches, while the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ) oscillated northward and southward with orbital rhythms.

-

Late-Glacial Variability: Even within the long glacial, brief mild interstadials brought short-lived reef growth spurts and pulses of vegetation recovery. Cooler phases depressed the coral-algal community but expanded coastal steppe and dry scrub.

-

Volcanic Activity: Continuous effusive volcanism in the Hawaiian Big Island and intermittent eruptions in the Societies, Marquesas, and Cooks rejuvenated landscapes, built fresh lava plains, and created ephemeral crater lakes and ash-fed soils.

Overall, Polynesia’s climate oscillated between cool, windy glacial stability and short warming pulses that allowed the reef crest and forest line to advance and retreat in rhythm with the global climate.

Biota & Baseline Ecology (No Human Presence)

Every island was its own closed laboratory of evolution.

-

Marine Life:

Coral communities fluctuated with sea level and temperature, but even under glacial suppression, shallow fringing reefs persisted. Fish, mollusk, turtle, and seabird populations were immense, their only predators sharks and seals. On outer banks like Midway, Tokelau, and Tuvalu, monk seals and turtles bred in numbers far exceeding modern densities. -

Terrestrial Life:

The higher islands—Hawaiʻi, Tahiti, Samoa, the Marquesas—carried dense montane forests in windward belts and dry woodland or grass steppe on leeward slopes. Cloud forests crowned the summits, capturing mist even under glacial dryness. Each island hosted unique, isolated assemblages of birds, insects, and plants, evolving in splendid isolation. -

Avian Realms:

Seabird supercolonies occupied cliffs and stacks, fertilizing soils with guano and enriching nearshore ecosystems. On atolls and cays, the air was dense with terns, boobies, and petrels—an avian kingdom uninterrupted by human disturbance.

Environmental Processes & Dynamics

-

Reef and Lagoon Evolution: Lower sea levels exposed broad reef flats, which weathered into limestone benches; with each brief warming, corals recolonized and built new terraces—a staircase of future lagoons.

-

Volcano–Erosion Cycles: Heavy rainfall on high islands carved deep amphitheaters (e.g., Waiʻanae, Koʻolau, and Tahiti’s ancient calderas), while aridity on leeward slopes preserved lava plains and dunes.

-

Marine Productivity: Upwelling zones around island chains created feeding grounds for pelagic fish and whales; kelp-like macroalgae likely formed dense nearshore beds in cooler zones, anchoring early “reef forest” ecologies.

-

Atmospheric Circulation: Persistent trades sculpted the cloud belts that would later define Polynesian ecological duality—lush windward valleys and dry leeward coasts.

Long-Term Significance

By 28,578 BCE, Polynesia’s physical and biological foundations were firmly in place:

-

Volcanic arcs had matured into high-island chains with deep, fertile amphitheaters and developing river networks.

-

Coral reef systems, though suppressed by glacial cooling, had established their long-term frameworks, ready to surge during Holocene sea-level rise.

-

Forest and reef ecologies had stabilized into enduring zonations—ridge forests, dry scrub, coastal strand, reef-flat, and pelagic edge—that would persist through the Holocene.

The epoch thus created Polynesia’s essential blueprint: a world of towering volcanic islands, expanding reef terraces, seabird-sustained fertility, and unbroken ecological isolation.

In the ages to come, these formations would become the living stage for one of Earth’s greatest human voyaging traditions—a future civilization built upon the deep-time architecture of glacial Polynesia.

South America (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — Refugia, Shelves, and the Two Southern Worlds

Geographic & Environmental Context

Late-Pleistocene South America was not one world but two adjoining worlds that barely overlapped:

-

South America Major—from the Northern Andes (Quito–Cuzco–Titicaca–Altiplano) across the Amazon–Orinoco trunks, the Guianas Shield, and the Atlantic Brazil shelf, down through Paraguay–Uruguay–northern Argentina to northern Chile—was a continent of depressed cloud belts, fragmented rainforests, and broadened coastal plains.

-

South America Minor—Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego, and the Magellan–Beagle archipelagos—was an ice-marginal realm of fjords, loess steppe, and shelf banks along two oceans, largely unpeopled at this time.

These natural subregions looked outward more than inward: South America Major was knit to the Pacific and Amazonian basins; South America Minor leaned into the Southern Ocean and subantarctic winds. Their contrasts anchor The Twelve Worlds claim that “region” is a loose envelope—the living units are the subregions.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The interval spans the build-up to the Last Glacial Maximum:

-

Andes & Altiplano: Temperatures were ~3–7 °C lower; glaciers expanded on high cordilleras; puna–páramo belts shifted downslope; springs and rock-shelter margins persisted.

-

Amazon/Guianas: Rainforest contracted into riparian and montane refugia, separated by savanna corridors; evapotranspiration fell; seasonality sharpened.

-

Atlantic Brazil shelf: Sea level ~100 m below modern exposed broad strand-plains; estuaries and deltas migrated seaward.

-

Atacama & high basins: Hyper-arid, cold plateaus with oasis springs and small lagoons.

-

Patagonia–Fuegia: Strong westerlies, permafrost or seasonal frost on the interior steppe; Cordilleran icefields calved into fjords; outer shelves widened on both coasts.

Heinrich/Dansgaard–Oeschger pulses toggled the continent between slightly wetter interstadials (refugia expand) and drier stadials (savannization and ice advance).

Lifeways and Settlement Patterns

Human presence before ~30 ka is debated. If present in this window, occupations were sparse and refugium-tethered; robust, widespread sites appear later, during deglaciation. The likely pattern:

-

South America Major

• Coasts (Pacific and Atlantic Brazil): Opportunistic foraging in upwelling coves and exposed strand-plains—shellfish, fish, seabirds—with short-stay dune or beach-ridge camps.

• Riparian lowlands (Amazon–Orinoco): Small groups anchored to gallery forests and levees—fish, turtles, capybara, supplemented by deer/peccary and palm fruits.

• Andean foothills & basins: Rock-shelter use near perennial springs; small-game, rodents, camelids at high elevations; wild tubers and chenopods along wet margins.

• Atacama oases: Patchy use of springlines and saline lagoons where available. -

South America Minor

• Likely unoccupied this early. Though kelp-forest corridors and rich fjord/shore ecologies existed (shellfish, pinnipeds, seabirds), sustained use is later (post-LGM, >14.5 ka north of the zone at Monte Verde).

Across the continent, potential foragers would have practiced short-radius mobility between water-secure nodes: coves ⇄ levees ⇄ springs ⇄ rock shelters.

Technology and Material Culture

Toolkits, where present, fit late Middle/early Upper Paleolithic expectations:

-

Stone: expedient flake–blade industries in quartz/quartzite and local cherts; retouched scrapers, burins, backed pieces late.

-

Organic: bone awls/points, digging sticks, nets/cordage (poorly preserved).

-

Pigment & ornament: ochre for body/adhesive use; simple beads (shell/seed) in later parts of the span are plausible.

These reflect light, portable technologies optimized for riparian and springline mobility, not heavy residential investment.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Even with low population density, the continent’s natural corridors were already set:

-

Pacific littoral “kelp highway”: cove-to-cove reconnaissance along upwelling margins (Peru–N. Chile).

-

Andean valley strings: spring/rock-shelter chains linking puna to foothills.

-

Amazon–Orinoco trunks: Solimões–Madeira–Xingu–Tapajós–Negro and Orinoco–Casiquiare provided levee driftways and portage nodes.

-

Atlantic strandlines: broad Brazilian shelf plains connected estuaries and lagoon belts.

In South America Minor, the Magellan–Beagle coasts and wide shelf banks were ecological scaffolding for the later maritime florescence.

Cultural and Symbolic Expressions

If present in this span, symbolic behaviors would mirror the global Upper Paleolithic repertoire at low intensity: ochre use, hearth structuring, simple ornament caches in shelters. The richest, unequivocal material appears after the interval, as deglaciation improves site survivorship and territory size.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

The operating logic of the age was refugium tethering:

-

Water-secure nodes—gallery forests, springlines, upwelling coves—anchored seasonal rounds.

-

Broad portfolios—aquatic + terrestrial—buffered aridity and cold snaps.

-

Topographic stacking (coast ↔ foothill ↔ puna; levee ↔ terra firme) created short-range substitutes when one niche failed.

In South America Minor, kelp forests, guanaco steppe, and shelf banks formed the “later-use” safety net awaiting Holocene colonists.

Transition Toward Deglaciation

By 28,578 BCE, Andean ice began its slow retreat, rainforest corridors poised to reconnect, and coastal/riverine pathways to improve:

-

South America Major was primed for the unequivocal Late Pleistocene/Early Holocene occupations—shell-midden coasts, levee hamlets, puna caravan trails—that will define its next chapter.

-

South America Minor held its ecological stage set—fjords, archipelagos, and kelp lanes—for the post-LGM maritime foragers who would turn the far south into a canoe world.

In short, the continent already displayed the dual structure central to The Twelve Worlds: a peopled northern–central theater of refugia and corridors beside an unpeopled southern theater of ready-made ecologies—two neighboring worlds whose destinies would diverge as the ice let go.

South America Minor (49,293–28,578 BCE)

South America Minor includes southern Chile (incl. Central Valley), southern Argentina (Patagonia south of the Río Negro/Río Grande), Tierra del Fuego, Falkland/Malvinas, Juan Fernández.

Anchors: Patagonian steppe, Andean icefields, Strait of Magellan–Beagle Channel, Fuegian archipelago, Pacific fjords, Atlantic shelf banks.

Geographic & Environmental Context

-

Cordilleran ice sheets dominated the southern Andes; outlet glaciers sculpted fjords and moraines.

-

Patagonian steppe: cold, windy; periglacial dunes/loess.

-

Sea-level lowstand exposed broad Atlantic shelves and expanded Magellan–Beagle shorelines.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

LGM: strong westerlies, low temperatures, aridity inland; permafrost/seasonal frost common on steppe.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Human occupation in this early window is unlikely; robust evidence appears much later (>14.5 ka at Monte Verde to the north).

-

Productive kelp highway ecologies existed (shellfish, pinnipeds, seabirds), but sustained use likely post-LGM.

Technology & Material Culture — N/A (pre-human).

Movement & Interaction Corridors — N/A (pre-human).

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions — N/A.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Ecological scaffolding (kelp forests, shelf banks, guanaco steppe) set the later human adaptive palette.

Transition

-

Deglaciation and shelf flooding will open fjord/archipelago routes, enabling the well-documented Holocene maritime foragers of the southern cone.

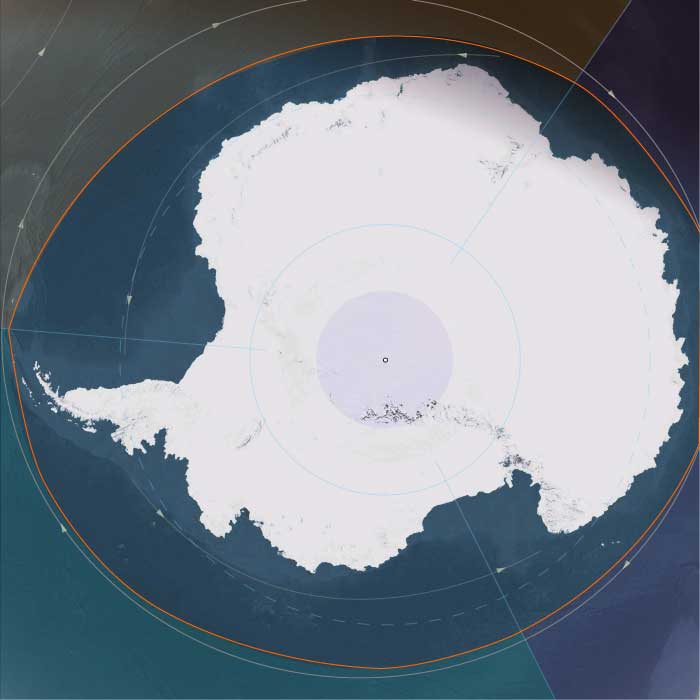

Antarctica (49,293–28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — The Frozen Continent and Its Oceanic Halo

Geographic and Environmental Context

During the height of the Late Pleistocene, Antarctica stood as the coldest, driest, and most isolated world on Earth—a continent sealed in ice and girdled by the Southern Ocean.

The great landmass divided naturally into three broad realms:

-

East Antarctica, the immense polar plateau rising more than 3 km above sea level, draped in ice more than 4 km thick and stretching from the Transantarctic Mountains to the Indian Ocean rim.

-

West Antarctica, a lower, fractured terrain comprising the Antarctic Peninsula, Marie Byrd Land, and the Amundsen–Ross embayments, fringed by vast floating shelves.

-

The subantarctic ring—the nearby island arcs of South Georgia, the South Orkneys, the South Sandwich Islands, Bouvet, and the Prince Edward–Marion chain—sat just beyond the continental ice but within its climatic orbit, forming Antarctica’s ecological frontier with the world’s oceans.

These divisions—polar plateau, continental rim, and subantarctic ring—behaved less like a single geography than like three interconnected systems whose unity was maintained by ice, wind, and current.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The period between 49,000 and 28,500 BCE encompassed the build-up to the Last Glacial Maximum.

-

Temperature: Mean annual values across the plateau were 10–15 °C colder than today; coastal sectors remained below freezing even in summer.

-

Ice extent: The East Antarctic Ice Sheet thickened and spread toward the coast, while the smaller West Antarctic ice masses merged, grounding on the continental shelf. Overall, Antarctica’s ice volume reached its greatest Quaternary extent.

-

Sea level: Global levels fell ~120 m, exposing continental shelves and expanding grounded ice.

-

Atmosphere: Lower greenhouse-gas concentrations and stronger katabatic winds intensified polar deserts in the interior.

-

Ocean: Sea-ice fronts advanced far north in winter, yet polynyas—open-water oases—persisted along parts of the coast, sustaining remarkable marine productivity.

The result was a planet tipped toward cold equilibrium: Antarctica at its broadest and most luminous, radiating sunlight back into space and anchoring global climate.

Flora, Fauna, and Ecology

Antarctica itself supported only microbial, algal, and cryptogamic life confined to small ice-free niches, while its surrounding seas and subantarctic islands hosted some of Earth’s richest cold-water ecosystems.

-

Terrestrial oases: Along the Dry Valleys, the Antarctic Peninsula, and scattered nunataks, thin melt-season films supported cyanobacteria, mosses, lichens, and minute invertebrates.

-

Coastal wildlife: Adélie and early emperor-penguin lineages bred on stable sea-ice platforms; skuas and petrels nested on rocky ledges.

-

Marine systems: Krill, copepods, and under-ice algae flourished beneath seasonal pack ice, feeding whales, seals, and seabirds.

-

Subantarctic ring: Islands like South Georgia and the Prince Edward group carried tussock grass, moss, and sprawling rookeries of albatrosses, petrels, and fur seals—vital nodes in the circum-polar web.

Though barren by continental standards, Antarctica’s margins were alive with motion, its biological clock synchronized to the annual advance and retreat of ice.

Human Presence and Global Context

No humans had ever set foot on this continent or its islands.

Elsewhere, Homo sapiens spread across Africa, Eurasia, and Sahul, but Antarctica lay far beyond the technological reach of any Pleistocene mariner.

Its isolation rendered it the world’s ultimate terra incognita, absent even from myth.

Yet indirectly, it mattered: the continent’s albedo, sea-ice cycles, and carbon sequestration steered the climates within which human civilizations would one day arise.

Antarctica was already humanity’s silent climate engine.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Though devoid of people, the region was a crossroads for wind, current, and life:

-

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) encircled the continent, connecting the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans into a single conveyor.

-

The westerly wind belt (“roaring forties” – “furious fifties”) drove surface circulation and upwelling that fed krill blooms.

-

Whales, seals, and seabirds migrated along these highways from every southern continent, forming a truly circum-global ecological network.

These corridors prefigured the pathways of future exploration, commerce, and science.

Symbolic and Conceptual Role

In human terms, Antarctica existed only as an absence—a mythic void beyond any known horizon.

Had Ice-Age peoples imagined it, it might have represented the under-world of ice, a place where sun and earth froze in perpetual night.

In geological reality, it was the earth’s mirror, reflecting heat and regulating balance: a physical metaphor for stasis at the edge of creation.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Antarctica’s ecosystems, though sparse, showed immense stability:

-

Glacial resilience: Microbial and moss communities endured multiple glacial advances, recolonizing from refugia during brief interstadials.

-

Marine adaptation: Krill and fish species evolved antifreeze proteins, surviving under permanent cold.

-

Carbon storage: Ice-sheet expansion sequestered atmospheric CO₂, tightening Earth’s glacial grip yet ensuring reversibility when melting resumed.

In every process—wind, ice flow, nutrient recycling—the system demonstrated the capacity of life and climate to adapt through feedback and equilibrium.

Transition Toward the Glacial Maximum

By 28,578 BCE, Antarctica had reached near-peak glacial extent.

The East Antarctic plateau remained unaltered in its frozen dominion; the West Antarctic shelves thickened; and the subantarctic islands thrived as refugia for the Southern Ocean’s living abundance.

Humanity still knew nothing of this world, yet its influence touched every other: it cooled the tropics, lowered the seas, and sculpted the very margins of habitable Earth.

In the grand pattern of The Twelve Worlds, Antarctica stood as the still point of the planet’s climatic wheel—its icy heart, unseen but omnipresent, binding the glacial age together.

Polynesia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene Transition — Emerging Arcs, Drowned Plateaus, and Reef Foundations

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Late Pleistocene and early Holocene, Polynesia—stretching from the Hawaiian archipelago across Samoa, Tonga, the Cook and Society Islands, to the far eastern outliers of Pitcairn and Rapa Nui—remained entirely unpeopled, a scattered constellation of volcanic and reefed islands rising above the world’s largest ocean.

At the Last Glacial Maximum (c. 26,500–19,000 BCE), global sea levels stood more than 100 m lower than today, exposing wide coastal shelves and tightening inter-island channels. As ice sheets melted, deglaciation flooded ancient shorelines, transforming basins into lagoons and seamounts into isolated atolls.

-

North Polynesia (Oʻahu, Maui Nui, Kauaʻi–Niʻihau, Midway Atoll): the Maui Nui shelf—once a single island—became a cluster of channels; Midway’s rim expanded as new lagoons formed.

-

West Polynesia (Hawaiʻi Island, Tonga, Samoa, Tuvalu–Tokelau, Cook, Society, and Marquesas): reefs and barrier lagoons built up around volcanic peaks, while low atolls appeared as sea level rose.

-

East Polynesia (Pitcairn, Rapa Nui, and nearby seamounts): the farthest outposts of the Pacific, geologically young and ecologically self-contained, fringed by narrow reef flats and rich upwelling zones.

Across this immense realm, oceanic currents—the South and North Equatorial and the Kuroshio–Equatorial Counter-flow system—created predictable gyres, establishing the hydrological backbone that would later sustain Polynesian voyaging.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The epoch was one of oscillation and renewal:

-

Last Glacial Maximum (26,500–19,000 BCE): cooler seas and exposed shelves expanded coastal plains; coral growth slowed under lowered sea level.

-

Bølling–Allerød interstadial (c. 14,700–12,900 BCE): warmth and rainfall increased; reefs surged upward in “catch-up” growth; lagoons and barrier formations matured.

-

Younger Dryas (12,900–11,700 BCE): brief cooling flattened reef accretion and restricted mangroves; trade-wind aridity spread in leeward belts.

-

Early Holocene (after 11,700 BCE): steady warming and sea-level stabilization allowed coral terraces, mangroves, and strand forests to reach near-modern equilibrium.

By 7822 BCE, the Pacific climate engine had achieved its Holocene rhythm—warm, humid, and oceanically stable.

Biota & Baseline Ecology (No Human Presence)

Polynesia’s ecosystems reached pristine balance under rising seas:

-

Reefs and lagoons flourished with coral, mollusks, crustaceans, and reef fish (parrotfish, surgeonfish, mullet); spur-and-groove structures and back-reef ponds became marine nurseries.

-

Coastal vegetation—pandanus, beach heliotrope, ironwood, and grasses—rooted in guano-enriched sands; strand forests stabilized dunes.

-

Cloud-forests cloaked high islands such as Tahiti and Savaiʻi, while dry leeward slopes supported shrub and palm mosaics.

-

Seabirds nested in immense colonies; turtles hauled out on beaches; marine mammals frequented newly formed bays.

All existed in predator-free isolation, each island a laboratory of speciation and resilience.

Geomorphic & Oceanic Processes

As the sea rose, island landscapes underwent continuous re-sculpting:

-

Reef accretion kept pace with transgression, forming the first true atoll rings.

-

Maui Nui’s plateau fragmented into separate islands; Hawaiʻi Island’s volcanic plains met new coasts.

-

Eastern high islands (Rapa Nui, Pitcairn) gained fertile volcanic soils through slow weathering; storm surges and wave reworking created terraces and embayments.

-

Sediment deltas at stream mouths formed early estuarine wetlands—future sites for Polynesian fishponds and irrigated terraces.

Symbolic & Conceptual Role

For millennia these lands remained beyond the human horizon—unimagined yet forming the ecological architecture that would one day welcome voyagers. Their mountains, lagoons, and reefs became the stage on which later Polynesian societies would enact origin stories of sea and sky.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Natural resilience was inherent:

-

Coral reefs tracked rising seas through vertical growth, preventing ecological collapse.

-

Guano-fertilized soils accelerated vegetative colonization after storm disturbance.

-

Cloud-forest hydrology maintained water flow even in drier pulses.

These feedbacks produced long-term equilibrium between land, sea, and atmosphere—the defining ecological rhythm of Polynesia.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, Polynesia had become a fully modern oceanic system: drowned plateaus transformed into lagoons and atolls; coral terraces and forest belts stabilized; seabird and reef ecologies reached peak diversity.

Though still empty of humankind, the region now possessed every element—predictable currents, fertile reefs, sheltered bays, and stable climates—that would, tens of millennia later, make it the natural cradle of the world’s greatest voyaging tradition.

Antarctica (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Upper Pleistocene II → Early Holocene — Ice, Ocean, and the Edges of Life

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the transition from the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) to the Early Holocene, Antarctica remained a continent of deep ice and shallow change—a frozen core slowly responding to planetary warming.

Its three major regions reflected stark gradients of cold, wind, and ecological possibility:

-

Eastern East Antarctica — the vast polar plateau rising over 3,000 m, capped by ice up to 4 km thick and rimmed by the Amery, Shackleton, and Ross Sea shelves. A hyper-arid interior where snow accumulation was minimal and temperatures rarely rose above –40 °C.

-

Western East Antarctica — the coastal fringe along the Indian and Atlantic sectors and its subantarctic island arc (South Georgia, South Sandwich, South Orkney, Bouvet, Prince Edward–Marion, western Kerguelen). Cold, wet, and windy, these islands were the biological outposts of the polar world.

-

West Antarctica — including the Antarctic Peninsula, Ellsworth Mountains, Marie Byrd Land, and the great Ross and Filchner–Ronne shelves. Ice streams here flowed into subpolar embayments, while geothermal oases and ice-free headlands supported sparse but persistent life.

Together they formed a mosaic from permanent polar desert to storm-lashed tundra, all encircled by the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC)—the engine linking the Southern Ocean to every other sea.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Last Glacial Maximum (c. 26,500 – 19,000 BCE):

The Antarctic Ice Sheet was thicker and broader than today. Ice shelves reached the continental-shelf edge; sea ice expanded hundreds of kilometers northward each winter. Mean annual temperatures were 6–10 °C colder than modern values. -

Bølling–Allerød (c. 14,700 – 12,900 BCE):

Global warming marginally softened coastal climates. Seasonal sea ice contracted slightly in summer, exposing rocky beaches for brief biological colonization. -

Younger Dryas (c. 12,900 – 11,700 BCE):

Cooling restored extensive winter sea ice; outlet glaciers paused or advanced; westerly winds strengthened. -

Early Holocene (post-11,700 BCE):

Renewed warmth reduced ice extent along the Antarctic Peninsula and Ross–Amundsen coasts; polynyas widened; ice-free ground on subantarctic islands expanded. Interior East Antarctica remained effectively unchanged—still the planet’s coldest desert.

Flora, Fauna & Ecology

Life was confined to coastal oases, volcanic slopes, and the surrounding seas:

-

Mainland Antarctica:

• Lichens, mosses, and microbial mats in ice-free pockets near geothermal sites and rocky headlands.

• Adélie and early Emperor penguins nesting on stable fast-ice or gravel beaches.

• Weddell, leopard, and crabeater seals using tide cracks and polynyas for breeding. -

Subantarctic islands:

• Tundra vegetation—tussock grasses, mosses, and cushion plants—spread on newly deglaciated slopes.

• Immense rookeries of albatrosses, petrels, penguins, and fur or elephant seals.

• Peat initiation began in saturated hollows, creating long-term carbon sinks. -

Marine realm:

• Seasonal phytoplankton blooms at the ice edge supported vast krill swarms, anchoring the food web for whales, seals, and seabirds.

• Nutrient-rich upwelling sustained the Southern Ocean as Earth’s most productive cold-water ecosystem.

Human Presence

None.

Antarctica remained completely beyond the reach of late Pleistocene navigation and survival technology. Its existence was outside any cultural geography or mythic horizon.

Environmental Dynamics

-

Ice-flow systems transported snow from the plateau to the sea, feeding the great shelves.

-

Calving and polynyas drove marine productivity by mixing surface and deep waters.

-

Volcanism in Marie Byrd Land, the South Shetlands, and South Sandwich arc created minor geothermal refuges that harbored unique biota.

-

Subantarctic feedback loops: guano deposition, peat formation, and storm redistribution of nutrients knit ocean and land into one biogeochemical engine.

Symbolic & Conceptual Role

For every human society of this time, Antarctica did not yet exist—not as rumor, myth, or destination. It was a planetary absence, sensed only through distant weather and current systems that touched Africa, South America, and Australasia.

South America (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Upper Pleistocene II → Early Holocene — Deglaciation, Reconnected Refugia, and Littoral Gateways

Geographic & Environmental Context

From the Quito–Cuzco–Titicaca–Altiplano to the Orinoco–Llanos, across the Amazon (Solimões–Madeira–Xingu–Tapajós–Marajó) and the Guianas Shield, and along the still-broadened Atlantic Brazil shelf and the upwelling coasts of Peru–northern Chile, South America entered the Early Holocene as a continent of rising mountains and rising seas.

In the south, South America Minor—Patagonia south of the Río Negro/Río Grande, the Strait of Magellan–Beagle Channel, Tierra del Fuego, and the Falkland/Malvinas–Juan Fernández outliers—saw Cordilleran icewithdraw into high cirques, carving fjord labyrinths west of the Andes and leaving proglacial lakes and steppe plateaus to the east.

Postglacial sea-level rise, still ~60–80 m below modern early in the period, flooded coastal benches into ria-like embayments and back-reef lagoons, particularly along Atlantic Brazil and the Caribbean margins, even as the Humboldt upwelling sustained kelp and shell-rich coves on the Pacific side.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Bølling–Allerød (c. 14.7–12.9 ka): Warmer, wetter pulses reforested Amazonian and Orinocan refugia, stitched by major river corridors; Andean hydroclimates stabilized as puna and páramo belts crept upslope. Along the Pacific rim, upwelling cells fueled rich nearshore webs; on the Atlantic side, a still-broad shelf supported expansive strandplains and lagoons.

-

Younger Dryas (c. 12.9–11.7 ka): A cool/dry setback narrowed forest corridors, invigorated steppe in leeward interiors, and heightened reliance on littoral and riverine proteins.

-

Early Holocene (post-11.7 ka): Monsoons strengthened; Amazonian gallery forests re-expanded and linked; Andean snowlines retreated; estuaries and lagoons from Marajó to Santa Catarina and along Peru–Atacamastabilized as sea level rose toward modern positions.

Subsistence & Settlement

By ~13–12 ka, humans were widely established from Pacific Peru to the Andean forelands and major lowland trunks; settlement was semi-recurrent and water-anchored, with strong coastal–river–valley coupling:

-

Pacific littoral (Peru–N. Chile): Coves within the Humboldt Current hosted intensive harvest of shellfish, rockfish, anchoveta, sea lions, seabirds, and seaweeds, likely via raft/dugout logistics along a proto “kelp highway.” Shell scatters and strandline hearths signal repeated use of the same landings.

-

Andean valleys & puna: Rock-shelter and terrace hamlets targeted deer, vicuña/guanaco, vizcacha and caviomorph rodents, and wild tubers; riparian stands (e.g., chenopods, amaranths) were increasingly curated and processed on grindstones. Seasonal rounds linked high-puna hunts to valley springs and alluvial plots.

-

Amazon–Orinoco lowlands & Guianas: Wet-season camps on natural levees exploited fish, turtles, caimans, capybara, and abundant palm fruits; varzea/igapó mosaics encouraged orchard-garden tending around hamlets. On the Guianas Shield, foragers navigated inselberg–savanna–gallery forest patchworks with broad-spectrum diets.

-

Atlantic Brazil strandplains: A still-wide coastal plain nurtured early shell-midden nuclei at estuary mouths and dune-lagoon fringes, where bivalves, crustaceans, finfish, and marine mammal remains attest to repeated feasting and aggregation.

-

South America Minor (Patagonia–Fuegia): Along the fjord and channel coasts, foragers exploited kelp-forest seams (mollusks, fish, sea mammals) and likely staged short canoe/raft crossings; east of the Andes, steppe camps organized around guanaco drives, rhea hunts, and lake-margin waterfowl.

Across the continent, communities tethered to refugial nodes—springs, levees, coves, and rock shelters—while maintaining seasonal mobility across adjacent ecozones.

Technology & Material Culture

Toolkits balanced expedient mobility with targeted specialization:

-

Lithics: pervasive microlithic flake–blade industries; backed bladelets, scrapers, burins; regional obsidian/siliceous networks in Andean forelands and Patagonian steppes.

-

Aquatic gear: bone gorges and harpoons, composite points, net floats/sinkers; stake-weirs and basket traps emergent on salmon-bearing and whitefish rivers by late in the period.

-

Processing tools: grindstones/querns in Andean and lowland contexts for seeds, tubers, and pigment; shell adzes in littoral zones.

-

Containers & clothing: organic carriers (gourds, bark, skin), early netting and twined bags; tailored hides; ochre for body/ritual use; shell/seed/teeth ornaments in burials and feast contexts.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Deglaciation and rising seas reconfigured, but did not diminish, connectivity:

-

Pacific kelp-forest corridor: cove-to-cove and island-to-island movements along Peru–N. Chile’s productive littoral.

-

Andean valley strings: rock-shelter nodes at springs and passes (Cochabamba, Puna de Atacama, Cuzco–Titicaca arc) linked high–mid–low altitude resource zones.

-

Amazon–Orinoco trunks: Solimões–Madeira–Xingu–Tapajós–Negro–Orinoco served as driftways and portage chains, coupling previously isolated forest refugia.

-

Atlantic strandlines: broad Brazilian shore supported early along-shore movement between lagoon fisheries and stone/palm resources inland.

These braided pathways moved dried fish and meats, palm starch/oils, lithics, pigments, and stories, re-knitting the continent after the LGM.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Water and stone framed early ritual landscapes:

-

Rock shelters in Andean and foreland belts preserved hearths, pigment floors, and engraved/painted panels, marking places of teaching, exchange, and ceremony.

-

Shell-mounds on Pacific and Atlantic coasts functioned as feast and ancestor markers, accumulating over generations at favored landings.

-

Ochred burials and personal adornments (shell/seed/teeth beads) bespeak lineage memory and emerging territoriality, often at river mouths, levees, and springs.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Resilience rested on refugia-tethered, multi-sited portfolios:

-

Refugium anchoring (lagoons, levees, springs) ensured dependable access to water and food as climate oscillated.

-

Broad-spectrum diets—littoral proteins paired with riparian and forest fare—buffered interannual variability, especially through the Younger Dryas cool/dry interval.

-

Seasonal scheduling across coast–valley–puna and river–terra firme–floodplain gradients spread risk; early orchard/patch management around camps enhanced reliability.

-

Storage of smoked fish and meat, roasted seeds/tubers, and rendered oils sustained longer stays and supported semisedentism.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, deglaciated Andean valleys, re-connected Amazon–Orinoco forests, and stabilizing littorals sustained semi-recurrent camp landscapes and nascent shell-midden nodes.

In the south-cone, dual kelp-edge and steppe economies were firmly in place, poised for the canoe-borne traditions of the Fuegian channels.

Across South America, the operating code of the coming Holocene was already legible: water-anchored, broad-spectrum subsistence; mobility braided to refugial anchoring; early plant tending; food storage; and ritualized claims to the enduring places that made life secure.

South America Minor (28,577–7,822 BCE) | Upper Pleistocene II: Deglaciation, Kelp-Edge Shores, and Steppe Gateways

Geographic & Environmental Context

South America Minor includes southern Chile (incl. Central Valley), southern Argentina (Patagonia south of the Río Negro/Río Grande), Tierra del Fuego, Falkland/Malvinas, Juan Fernández.

Anchors: Patagonian steppe, Andean icefields, Strait of Magellan–Beagle Channel, Fuegian archipelago, Pacific fjords, Atlantic shelf banks.

-

Cordilleran icefields retreated, carving deep fjords along southern Chile; proglacial lakes dotted the eastern steppe.

-

Atlantic shelves broadened; coastal banks enriched fisheries.

-

Strait of Magellan–Beagle shores gained new landing coves.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Bølling–Allerød warming opened grasslands and woodlands; Younger Dryas reintroduced cold/dry steppe; strong westerlies persisted.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Human presence in the wider south-cone by >14.5 ka (e.g., Monte Verde just north of this subregion) expanded into our zone:

-

Pacific fjords/kelp coasts: shellfish, fish, sea lions, seabirds; shore whaling/scavenging; seaweeds.

-

Patagonian steppe: guanaco hunts; rhea; small game; waterfowl at lakes.

-

Magellan–Beagle: fortified coves used for seasonal aggregation; strand-midden nuclei formed.

-

Technology & Material Culture

-

Flake–blade microlithic industries; bone/antler points; fish gorges; harpoons; hide scrapers; fire-hearths/ovens in coves.

-

Early raft/canoe craft (probable) for short crossings.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Kelp highway along Pacific; fjord/archipelago stepping-stones to Fuegian realm.

-

Steppe: spring–lake circuits; Andean passes to leeward zones.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Rock-shelter paints/engravings in steppe margins; shell-midden feasting signatures.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Dual coastal–steppe scheduling hedged against cold pulses and resource crashes; storability (smoked meat/fish) prolonged residency.

Transition

By 7,822 BCE, southern cone foragers had staked coast–steppe dual economies, poised for canoe lifeways in Fuegian channels.

East Polynesia (28557 – 7822 BCE): The Far-Flung Isles of the Empty Ocean

Geographic and Environmental Context

East Polynesia—including the Pitcairn Islands, Easter Island (Rapa Nui), and nearby seamounts—formed the far eastern apex of the Polynesian Triangle.

-

These islands are oceanic in origin, volcanic or uplifted, and extremely isolated from any continental landmass.

-

During the Late Pleistocene, lower sea levels slightly increased land area on some islands, exposing coastal terraces and enlarging reef flats.

-

The surrounding Pacific was influenced by the South Equatorial Current, which brought warm waters year-round.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

Last Glacial Maximum (c. 26,500 – 19,000 BCE): Slightly cooler sea-surface temperatures and lowered sea levels affected reef growth rates; exposed coastal flats expanded nesting areas for seabirds and turtles. Rainfall remained moderate due to the islands’ equatorial–subtropical position.

-

Bølling–Allerød (c. 14,700 – 12,900 BCE): Warmer, wetter conditions boosted reef productivity; coastal vegetation flourished, and seabird populations increased.

-

Younger Dryas (c. 12,900 – 11,700 BCE): Modest cooling and seasonal rainfall variation slightly reduced vegetative growth rates, but ecosystems remained generally stable.

-

Early Holocene (after c. 11,700 BCE): Rising seas flooded exposed coastal terraces and reestablished modern shorelines; coral reefs expanded rapidly under warm, stable conditions.

Flora, Fauna, and Ecology

-

Terrestrial flora consisted of coastal strand plants, scrub, and limited inland forest, maintained by nutrient input from seabird guano.

-

Birdlife was abundant, with dense colonies of petrels, terns, frigatebirds, and shearwaters.

-

Marine life included coral reef ecosystems rich in fish, mollusks, crustaceans, and marine turtles.

-

With no human presence, all terrestrial and marine species existed in predator-free ecosystems, leading to the survival of ground-nesting seabirds in vast numbers.

Human Presence

-

No evidence of human visitation exists for this epoch; the islands were beyond the reach of even the most advanced late Pleistocene voyagers.

-

Their extreme remoteness meant they remained outside the known seascape of contemporary coastal peoples.

Environmental Dynamics

-

Reef flats and lagoons served as nurseries for fish and invertebrates.

-

Volcanic activity, though minimal in this period, influenced soil fertility on younger islands.

-

Seasonal storm systems occasionally reshaped beaches and coastal vegetation belts.

Symbolic and Conceptual Role

For human societies elsewhere in the Pacific, these lands lay entirely beyond the known horizon, neither visited nor imagined.

Transition Toward the Holocene

By 7822 BCE, East Polynesia’s islands had stable climates, fully developed reefs, and undisturbed terrestrial ecosystems. They would remain untouched by humans until the remarkable long-distance voyages of the late Holocene Polynesian navigators.

The Ends of the Earth, one twelfth of the Earth’s surface, is bordered by the South Atlantic and South Pacific Oceans and includes Subcontinental South America, the Chonos Archipelago, Chiloé Island, Tierra del Fuego, the Falkland Islands, the remote Juan Fernández Islands (notably home to the marooned sailor Alexander Selkirk from 1704 to 1709, an experience thought to have inspired Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe), the even more remote Easter Island, and West Antarctica—the portion of Antarctica that lies within the Western Hemisphere and includes the Antarctic Peninsula.

Easter Island, culturally Polynesian yet governed by Chile, is among the most isolated inhabited islands in the world, positioned in the eastern South Pacific Ocean at the northwestern edge of The Ends of the Earth, along with the equally remote Pitcairn Islands.

The southeastern and southwestern boundaries divide West Antarctica from the much larger East Antarctica.

The northeastern boundary follows the approximate courses of the Colorado and Barrancas Rivers, which flow from the Andes to the Atlantic Ocean and are traditionally recognized as the northern limit of Argentine Patagonia.

For Chilean Patagonia, most geographers and historians identify its northern boundary at the Huincul Fault in the Araucanía Region.

HistoryAtlas contains 153 entries for The Ends of the Earths from the Upper Paleolithic period to 1899.

Narrow results by searching for a word or phrase or select from one or more of a dozen filters.