East Africa (1108 – 1251 CE): Kilwa’s …

Years: 1108 - 1251

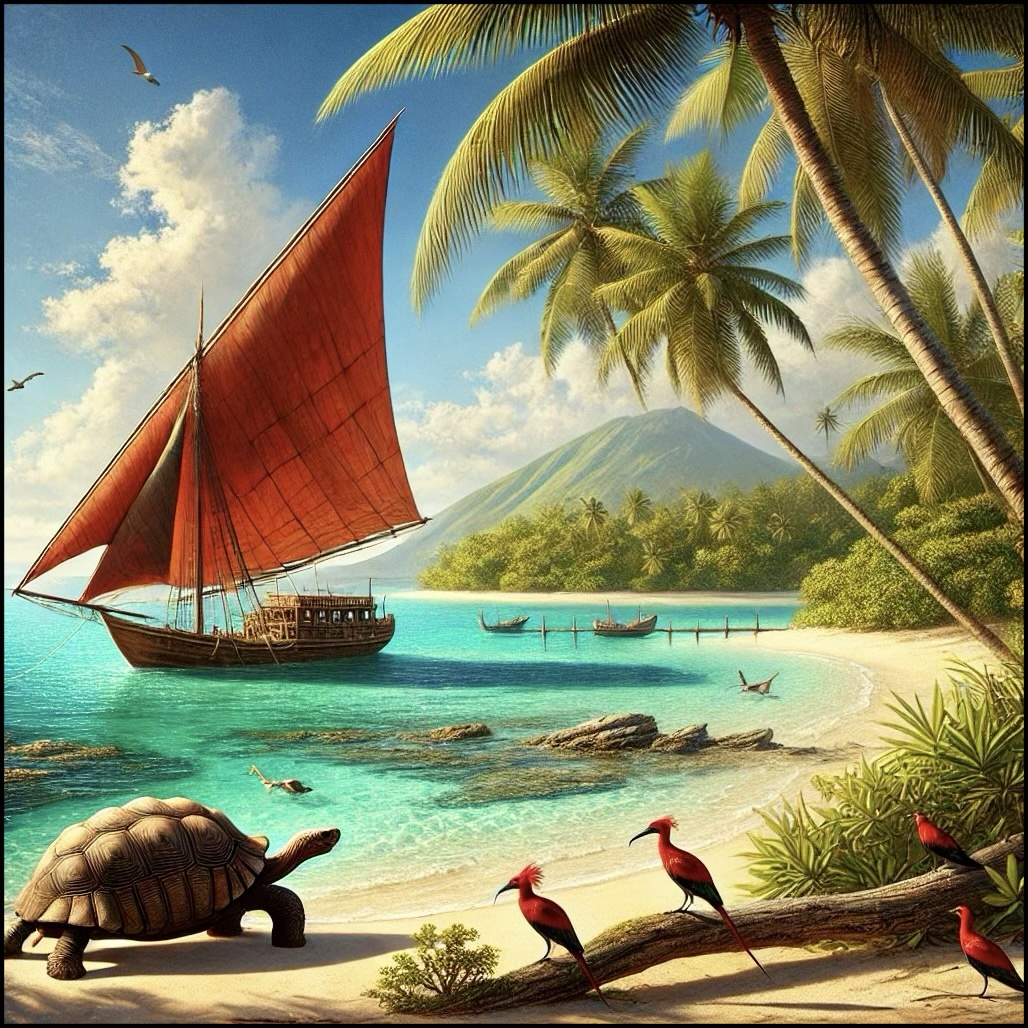

East Africa (1108 – 1251 CE): Kilwa’s Ascendancy and the Zagwe Golden Age

Between 1108 and 1251 CE, East Africa reached new heights of political, economic, and spiritual creativity.

Along the coast, Swahili-Islamic city-states flourished as maritime hubs of global commerce, while inland, the Zagwe kings of Ethiopia carved divine kingdoms in stone.

From the Red Sea highlands to the Great Lakes and the Zambezi plateau, communities harnessed environmental diversity and cultural synthesis to forge a continent-spanning network—Christian, Muslim, and indigenous—bound together by trade and faith.

This was the High Medieval age of East Africa, when Kilwa, Lalibela, and the Great Lakes monarchies shone as mirrors of both local genius and global connection.

Geographic and Environmental Context

East Africa united the Red Sea and Ethiopian Highlands with the Swahili Coast and interior river-lake basins.

Its geography formed three interconnected zones:

-

Maritime coasts and islands: coral-limestone shores, mangrove-fringed estuaries, and archipelagos from Lamu and Zanzibar to the Comoros and Madagascar.

-

Highlands and plateaus: fertile terraces and volcanic soils of Ethiopia, Uganda, Rwanda, and northern Zimbabwe.

-

Wetlands and river corridors: the Upper Nile, Great Lakes, and Zambezi–Caprivi systems, sustaining both herding and farming.

Monsoon winds joined these regions to the Indian Ocean world, while inland rivers—Nile, Zambezi, and Rufiji—linked them to Africa’s heartland.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The Medieval Warm Period provided stability, tempered by regional fluctuations.

-

Coastal monsoons remained predictable but saw greater cyclone frequency after 1200.

-

Ethiopian terraces and Great Lakes wetlands buffered dry years, sustaining steady population growth.

-

Madagascar’s climatic diversity—humid east, arid southwest—supported both rice cultivation and cattle herding.

-

Zambezi plateau and Okavango wetlands alternated between lush and lean years, encouraging mixed economies.

Ecological diversity became the foundation of resilience, enabling interdependence between coast, highland, and savanna.

Societies and Political Developments

The Swahili Coast and Kilwa’s Hegemony:

From Lamu to Sofala, coral-stone cities prospered on trade in gold, ivory, and slaves.

Kilwa Kisiwani, rising to preeminence after 1200, controlled the Sofala goldfields and extended authority southward into Mozambique.

Merchant councils governed cities like Mombasa, Zanzibar, and Malindi, while Comorian sultanates mediated between Africa, Arabia, and Persia.

Urban culture blended African, Arab, and Persian influences—visible in mosques, literature, and language (early Swahili).

Madagascar and the Indian Ocean Islands:

On Madagascar, kingdoms emerged: the Merina highland polity began forming, while Sakalava and Antemoro coastal groups thrived on trade.

Rice agriculture, cattle herding, and maritime exchange with the Swahili coast sustained prosperity.

The Comoros hosted Islamic dynasties; the Seychelles and Mascarenes, still uninhabited, served as navigational landmarks for monsoon sailors.

Zagwe Ethiopia and the Christian Highlands:

Inland, the Zagwe dynasty (1137–1270) brought political unity and spiritual splendor to Ethiopia.

At Roha (Lalibela), King Lalibela commissioned eleven rock-hewn churches, carved into living stone—a monumental renewal of Christian kingship.

Monasteries spread through the highlands, advancing literacy, terraced farming, and diplomacy with the Coptic Church in Egypt.

The dynasty’s legitimacy rested on holiness and architecture rather than Aksumite descent.

The Great Lakes Kingdoms:

Around Lake Victoria, early monarchies—Buganda, Bunyoro, Rwanda, Burundi—took shape under sacred kingship.

Rulers (mwami, mukama) coordinated land, ritual, and military service, supported by clan federations and ritual specialists.

In South Sudan, Dinka, Nuer, and Shilluk pastoralists expanded along floodplains, blending cattle cults with kin-based governance.

The Zambezi Plateau and Northern Zimbabwe:

North of the Zimbabwe heartland, small states linked copper, ivory, and grain production to Indian Ocean trade via Sofala.

Chiefs in Zambia’s river valleys and Zimbabwe’s northern hills directed copper and ivory caravans eastward, integrating inland and coastal economies.

Economy and Trade

Agrarian Wealth and Artisanal Innovation:

-

Ethiopia: highland agriculture (teff, barley, wheat, ensete) sustained monasteries and towns.

-

Great Lakes: bananas, millet, beans, and cattle formed interdependent systems.

-

Zambezi Plateau: copper and ivory exports; cattle-based wealth supported ritual and exchange.

-

Madagascar: rice and cattle production; exports of forest goods and iron tools.

Oceanic and Continental Exchange:

-

Gold and ivory from the interior reached the coast through Sofala, Kilwa, and Maputo Bay.

-

Imports included Indian textiles, Chinese porcelain, and Persian ceramics.

-

Red Sea ports (Massawa, Zeila) connected Ethiopia to Cairo and Alexandria.

-

Comorian and Malagasy merchants ferried rice, cattle, and aromatics into Swahili circuits.

Trade integrated three spheres—Indian Ocean, Nile, and Zambezi—into a single, diverse economic system.

Belief and Symbolism

Christianity and Monastic Kingship:

The Zagwe monarchs sanctified rule through monumental devotion.

The churches of Lalibela, carved into the earth, represented a spiritual “New Jerusalem.”

Pilgrimage and manuscript culture reinforced religious unity from Axum to Lake Tana.

Islam and the Swahili World:

Islam defined urban identity along the coast. Mosques, Quranic schools, and merchant endowments linked Kilwa, Zanzibar, and Comoros to Mecca and the Gulf.

Swahili literature, architecture, and coinage reflected a synthesis of African and Islamic expression.

Indigenous Spiritual Systems:

Inland communities—Nilotic, Bantu, and Malagasy—maintained ancestor veneration, rainmaking rites, and sacred kingship.

Across the Great Lakes and southern plateau, cattle cults tied spirituality to prosperity and fertility.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Terrace farming and irrigation in Ethiopia ensured high yields.

-

Fishing technologies—nets, weirs, canoes—sustained lakeside and delta communities.

-

Iron metallurgy flourished from Zambia to Uganda.

-

Stone architecture and coral masonry advanced in both highland and coastal centers.

-

Shipbuilding—dhows and sewn-plank vessels—enabled inter-island trade.

Technological diversity reflected the region’s ecological range—from mountain terraces to oceanic ports.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Red Sea–Highland route: Axum–Lalibela–Zeila–Cairo, connecting Ethiopia with Coptic Egypt.

-

Monsoon sea-lanes: Aden ⇄ Kilwa ⇄ Sofala ⇄ Comoros ⇄ Madagascar, maritime arteries of Indian Ocean trade.

-

Zambezi corridor: linked inland copper and ivory to Sofala’s coastal trade.

-

Great Lakes networks: canoe routes through Victoria, Albert, and Tanganyika fostered regional unity.

-

Nile floodplain: sustained exchange between Nilotic herders and Nubian intermediaries.

These intertwined corridors wove East Africa into both the African and global medieval economies.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Terraced agriculture and monastic stewardship in Ethiopia mitigated drought.

-

Wetland and deltaic cultivation buffered food supply in the Great Lakes and Zambezi basins.

-

Coastal cities diversified trade goods and alliances to survive monsoon variability.

-

Cultural synthesis—Christian highlands, Islamic coasts, and animist interiors—created flexible networks of diplomacy and exchange.

This regional pluralism was East Africa’s greatest strength, ensuring resilience amid shifting climate and politics.

Long-Term Significance

By 1251 CE, East Africa had become a continental crossroads of belief and exchange:

-

Zagwe Ethiopia represented a Christian state of artistic and spiritual majesty.

-

Kilwa and the Swahili coast dominated Indian Ocean commerce.

-

Great Lakes monarchies consolidated around sacred kingship and clan networks.

-

Madagascar entered the Swahili world through rice and cattle trade.

-

Copper, ivory, and gold flowed from the Zambezi and plateau into global markets.

The region stood united by diversity—a mosaic of kingdoms, city-states, and shrines—whose interwoven economies and faiths would sustain East Africa’s prominence in the centuries of Indian Ocean expansion that followed.

Maritime East Africa (with civilization) ©2024-25 Electric Prism, Inc. All rights reserved.

Groups

- Khoisan

- Bantu peoples

- Arab people

- Omanis

- Somalis

- Madagascar

- Nilotic peoples

- Persian Empire, Sassanid, or Sasanid

- Swahili people

- Islam

- Kilwa Sultanate