South Asia (909 BCE – 819 CE): …

Years: 909BCE - 819

South Asia (909 BCE – 819 CE): Iron Kingdoms, Oceanic Routes, and the Weave of Faiths

Regional Overview

Between the Hindu Kush and the southern capes of India stretched one of humanity’s most intricate civilizational tapestries.

From the Iron Age kingdoms of the Ganges plain to the maritime entrepôts of the Deccan and Sri Lanka, South Asia in the first millennium BCE – early CE was a world of transformation:

villages became towns, tribes became kingdoms, and merchants and monks carried ideas and goods from the Mediterranean to the South China Sea.

Two spheres balanced each other — the Upper South Asian interior, rooted in riverine agriculture and imperial administration, and the Maritime South Asian littoral, animated by monsoon commerce and cosmopolitan exchange.

Together they created a continental-oceanic civilization that fused agrarian power with maritime reach.

Geography and Environment

The northern heartland spanned the Indus–Ganga–Brahmaputra basins, shielded by the Himalayas and drained by some of the most fertile alluvium on Earth.

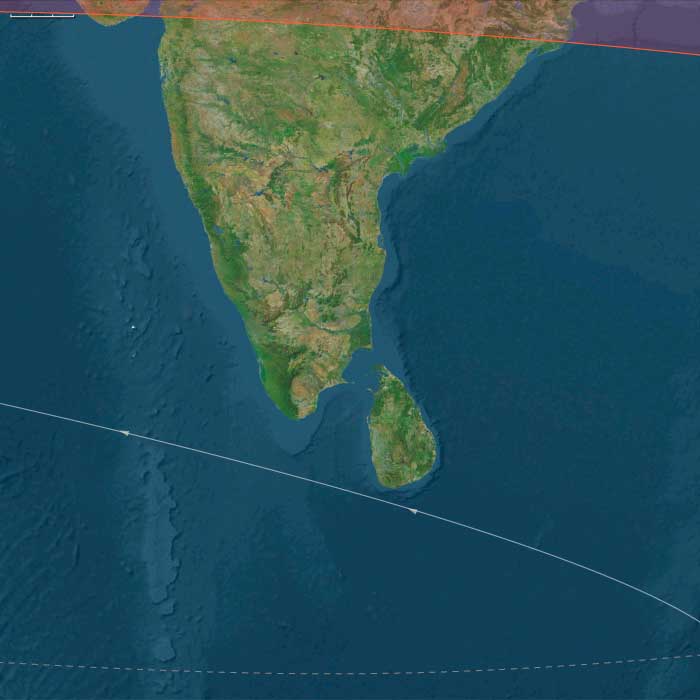

To the south rose the Deccan plateau and the coastal plains of Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Andhra, encircled by the Indian Ocean and threaded with river deltas.

Across the seas lay Sri Lanka, Lakshadweep, and the Maldives, forming stepping-stones toward Arabia and Southeast Asia.

Monsoon regimes shaped every aspect of life:

the southwest rains (June–September) watered rice fields and replenished tanks, while the retreating monsoon powered voyages west and east.

Periods of drought were met with irrigation ingenuity — canals, tanks, and stepwells that transformed the landscape into a man-made hydrology.

Societies and Political Developments

Upper South Asia: From Mahajanapadas to Empires

By the mid-first millennium BCE, iron plows and surplus agriculture supported the Mahajanapadas, the “Great States” of northern India — Magadha, Kosala, Kuru-Panchala, and others.

Out of this matrix emerged the Mauryan Empire (4th–3rd c. BCE), the subcontinent’s first large-scale polity, uniting much of India and Afghanistan under Chandragupta Maurya and later Aśoka.

Aśoka’s edicts, carved in stone across the empire, broadcast moral and administrative order and announced Buddhism as an imperial ethos.

After the Mauryas, regional powers filled the landscape: Indo-Greek and Śaka (Scythian) dynasts in the northwest; Kushan rulers linking Gandhara to Central Asia; and the Gupta Empire (4th–6th c. CE) in the Ganga heartland, whose classical Sanskrit culture defined art, science, and kingship for centuries.

The Hūṇas shattered Gupta unity, but the Pāla dynasty (8th–9th c.) revived Buddhist scholarship in Bengal and Bihar, sustaining the great universities of Nālandā and Vikramaśīla.

In the Himalayas, Licchavi Nepal and early Bhutanese polities bridged India and Tibet, while northern Arakan (Myanmar) connected the Ganga world to Southeast Asia.

Maritime South Asia: Deccan and Peninsular Polities

South of the Vindhyas, the Satavahanas (2nd c. BCE – 3rd c. CE) controlled the Deccan’s trade arteries, issuing coins in Prakrit and sponsoring Buddhist stupas along caravan routes.

Their successors — Ikshvakus, Vakatakas, Kadambas, Pallavas, Chalukyas, and the enduring Chera–Chola–Pandya triad of Tamilakam — built a patchwork of kingdoms linked by commerce and culture.

On the island of Sri Lanka, the Anurādhapura monarchy (from the 4th c. BCE onward) expanded vast irrigation tanks and monasteries, anchoring the Theravāda Buddhist tradition.

By the early centuries CE, these southern polities were exporting pepper, pearls, gems, and fine textiles through ports like Muziris, Arikamedu, and Kaveripattinam.

Greek, Roman, and later Chinese merchants arrived with coins and amphorae, while Indian sailors mastered the seasonal monsoon routes to the Red Sea and the Straits of Malacca.

Economy and Exchange

Agriculture formed the continental core — rice in the east, wheat and barley in the northwest, millet and pulses in the Deccan — sustained by iron tools and canal irrigation.

Trade networks extended in every direction:

-

Overland, through the Hindu Kush passes toward Persia and Central Asia;

-

Seaward, through the Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal to Africa, Arabia, and Southeast Asia.

Guilds (śreṇis) organized artisans and merchants; coins of silver, copper, and gold testified to a monetized economy.

Ports and caravanserais mirrored one another: harbors supplied pepper and pearls, while upland markets provided cotton and metals.

By integrating inland agrarian surplus with oceanic distribution, South Asia became the keystone between the Mediterranean and East Asia.

Technology and Material Culture

Advances in iron smelting, textile weaving, and architecture marked the age.

Stone and brick temples evolved from wooden prototypes; cave sanctuaries (Ajanta, Ellora) married engineering to faith.

In Sri Lanka, the hydraulic engineering of reservoirs and canals was among the most sophisticated in the ancient world.

Shipbuilding along both coasts produced plank-built vessels capable of open-ocean navigation, while astronomical knowledge guided monsoon sailing.

Art and literature flourished: Sanskrit epics and dramas, Prakrit poetry, Tamil Sangam anthologies, and Buddhist art from Gandhara to Amaravati conveyed a shared aesthetic of order and devotion.

Belief and Symbolism

Religious and philosophical plurality defined the region.

Vedic ritual evolved into Hindu devotional (bhakti) movements; Buddhism spread from the Ganga valley to Central Asia and Sri Lanka; Jainism flourished in western India.

Royal patronage crossed boundaries — Buddhist kings built Hindu shrines, Hindu dynasts endowed monasteries — reflecting a civilizational ethos of inclusivity and dialogue.

Symbolic architecture expressed cosmic geometry: the stupa as world-mountain, the temple as microcosm of the universe.

Adaptation and Resilience

Monsoon dependence fostered ingenuity: reservoirs, tanks, and flood-embankments turned uncertainty into reliability.

Polities survived invasion and drought by devolving power to local guilds and temples, creating layered sovereignty that could bend without breaking.

Maritime redundancy — alternate ports, seasonal scheduling — kept trade alive despite war or storm.

Cultural resilience came through translation and synthesis: foreign influences were absorbed, not imposed.

Regional Synthesis and Long-Term Significance

By 819 CE, South Asia had achieved an enduring civilizational equilibrium.

Its Upper sphere—from Gandhara and the Ganga to Bengal—embodied imperial administration, monastic learning, and continental coherence.

Its Maritime sphere—from the Deccan to Tamilakam and Anurādhapura—commanded the sea lanes, transmitting ideas and goods between worlds.

Each depended on the other: river basins fed the ports, and ocean trade enriched the plains.

This duality—continental and maritime—remains the natural division of South Asia, as visible in its geography as in its history.

Together they sustained a unified yet plural world, where faith, art, and commerce moved with the monsoon and where the ideals of Dharma, compassion, and cosmic order became the shared grammar of an entire region.

Groups

- Kirat people

- Gandhara grave, or Swat, culture

- Hinduism

- Gandhāra

- Vedic period

- Painted Grey Ware culture

- Kuru Kingdom

- Panchalas, Kingdom of the

- Kashi, Kingdom of

- Magadha Empire, Pradyota dynasty

- Gandhara, Kingdom of

- Mahajanapadas

- Magadha Empire, Haryanka dynasty

- Achaemenid Empire

- Kosala, Kingdom

- Jainism

- Achaemenid, or First Persian, Empire

- Buddhism

- Magadha Empire, Nanda Dynasty

- Kalinga

- Greece, Hellenistic

- Maurya Empire

- Shunga Empire

- Indo-Greeks, Kingdom of the

- Indo-Scythians

- Magadha, Kanva Kingdom of

- Kushan Empire

- Gandhāra

- Gupta Empire

- Guptas, Later

- Harsha (Harsavardhana), Empire of (Thaneswar)

- Gurjara-Pratihara

- Palas of Bengal, Empire of the

Commodoties

- Weapons

- Gem materials

- Colorants

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Fibers

- Textiles

- Strategic metals

Subjects

- Painting and Drawing

- Environment

- Decorative arts

- Faith

- Government

- Custom and Law

- Technology

- Philosophy and logic