Western Southeast Europe (1108 – 1251 CE): …

Years: 1108 - 1251

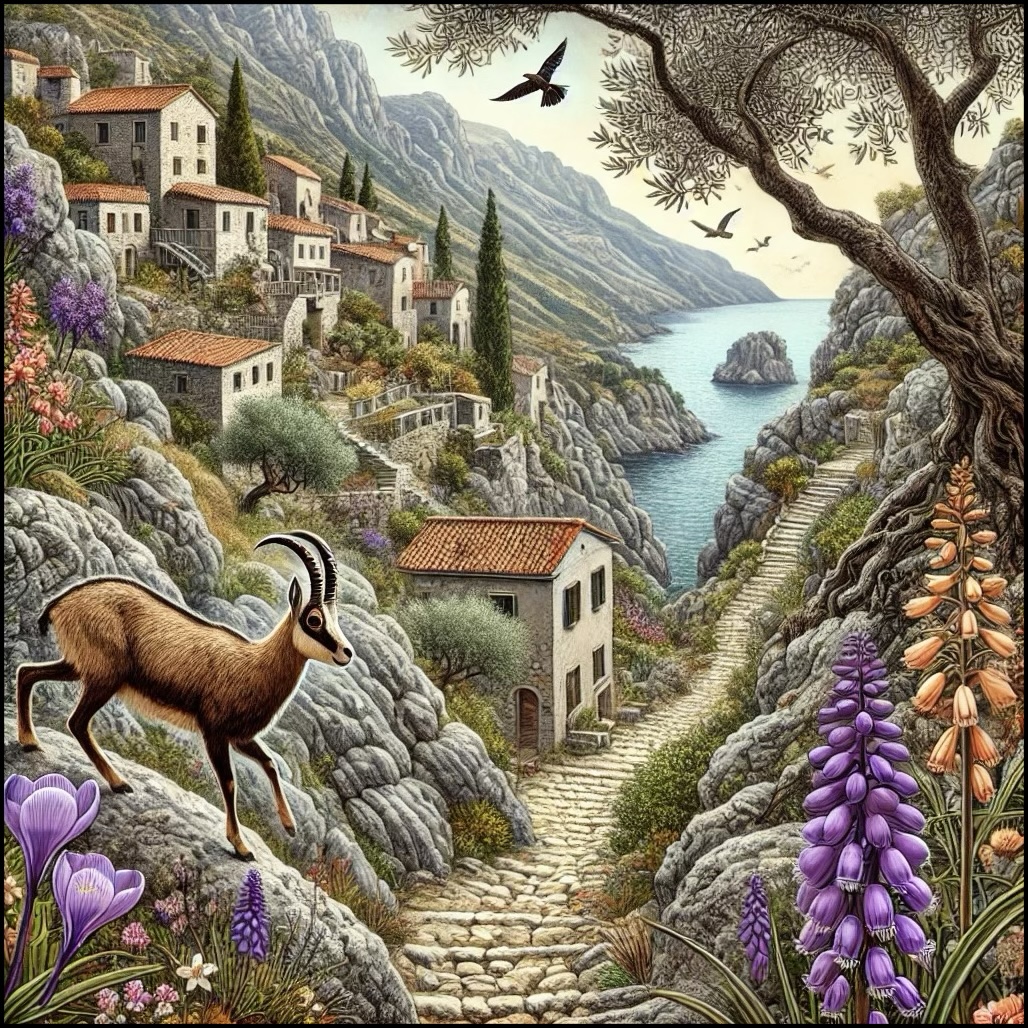

Western Southeast Europe (1108 – 1251 CE): Komnenian Shores, Nemanjić Serbia, and Venetian Dalmatia

Geographic and Environmental Context

Western Southeast Europe includes Greece (outside Thrace), Albania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Kosovo, most of Bosnia, southwestern Serbia, most of Croatia, and Slovenia.

-

Coastal lowlands and islands along the Adriatic (Dalmatia, the Ionian isles) met the Dinaric and Pindus mountains’ karst and upland pastures.

-

Interior corridors—Morava–Vardar, Drina–Sava, and the Via Egnatia from Dyrrachium (Durres) to Thessaloniki—linked the Aegean and Adriatic to the central Balkans.

-

River valleys and Mediterranean basins of Attica, Boeotia, Peloponnese, and Epiros anchored Byzantine agrarian themes.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

Gradual variability in precipitation; coastal agriculture and transhumance remained robust; maritime transport expanded.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Komnenian Byzantium (12th c.) secured Greek coasts and the Egnatian approaches; after 1204, the Despotate of Epirus and other Greek states (Achaea, Athens under Catalan Company from 1311, just beyond this age) emerged from the Latin partition.

-

Serbia (Nemanjić rise): Stefan Nemanja (r. 1166–1196) unified Raška; Stefan Nemanjić (the First-Crowned) became king (1217); Saint Sava secured autocephaly for the Serbian Church (1219), anchoring authority in Raška, Kosovo, and Metohija.

-

Croatia–Dalmatia: under the Hungarian Crown; after 1205, Venice dominated most Dalmatian communes; Ragusa (Dubrovnik) fell briefly to Venice, then maneuvered between overlords.

-

Bosnia: Ban Kulin (r. 1180–1204) fostered a prosperous, relatively autonomous banate focused on caravan tolls; successors maintained autonomy amid Hungarian claims.

-

Albania & Epirus: regional lords, then the Despotate of Epirus after 1204, controlled gateways to the Via Egnatia.

Economy and Trade

-

Silver (Bosnia/Serbia) and salt (Dalmatia) funded courts and communes; Ragusan and Venetian fleets moved Balkan produce to Italy and the Levant.

-

Inland caravan roads tied Novi Pazar, Prizren, and Skopje to Kotor and Ragusa.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Stone castles and walled communes; manuscript culture in Serbian monasteries; Latin notarial systems in ports; improved rigging and hulls for Adriatic galleys.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Adriatic convoys linked Dalmatia to Venice, Apulia, Sicily.

-

Via Egnatia (western reaches) remained the main east–west land trunk.

-

Vardar–Morava corridor funneled Serbian expansion southward.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Orthodoxy (Serbia, Greek states) and Latin Christianity (Dalmatia, Croatia) coexisted; Saint Sava institutionalized Serbian sacred kingship; coastal saints’ cults supported communal identity.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Pluri-polity landscape allowed merchants to switch flags and ports; ecclesiastical foundations stabilized rule and literacy.

Long-Term Significance

By 1251, Serbia stood as a crowned kingdom with an autocephalous church; Venice held Dalmatian seas; Epirus controlled western Greek gateways—frameworks that would lead into 14th-century zeniths and conflicts.

Western Southeast Europe (with civilization) ©2024-25 Electric Prism, Inc. All rights reserved.

People

Groups

- Slavs, South

- Greeks, Medieval (Byzantines)

- Venice, Duchy of

- Croats (South Slavs)

- Serbs (South Slavs)

- Roman Empire, Eastern: Macedonian dynasty

- Croatia, Kingdom of

- Christians, Roman Catholic

- Christians, Eastern Orthodox

- Dalmatia region

- Serbian Grand Principality

- Croatia, Kingdom of

- Athens, Duchy of

- Achaea, Principality of

- Epirus, Despotate of

- Serbia, Kingdom of

- Serbian Orthodox Church

- Achaea, Principality of

Topics

Commodoties

- Glass

- Domestic animals

- Oils, gums, resins, and waxes

- Grains and produce

- Textiles

- Ceramics

- Strategic metals

- Salt

- Beer, wine, and spirits

- Manufactured goods

- Money

- Aroma compounds