East Micronesia (1396–1539 CE): Navigational Networks and …

Years: 1396 - 1539

East Micronesia (1396–1539 CE): Navigational Networks and Island Chiefdoms

Geographic & Environmental Context

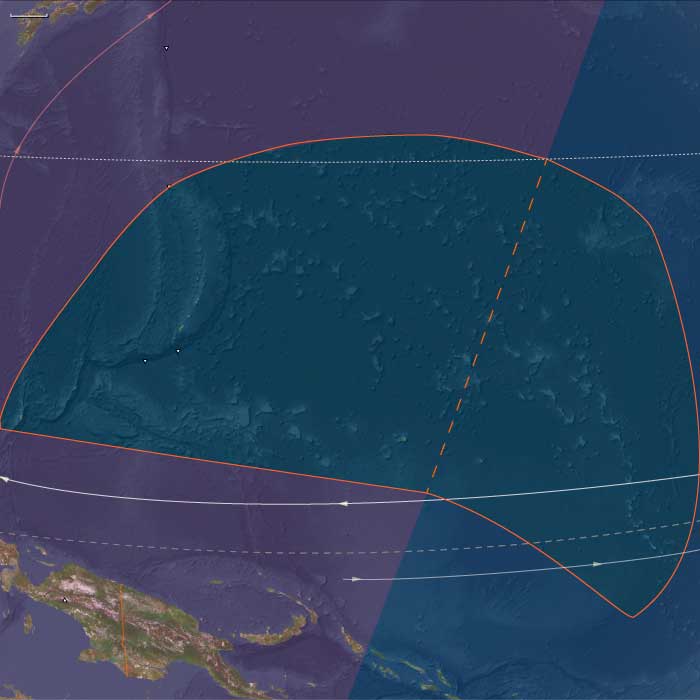

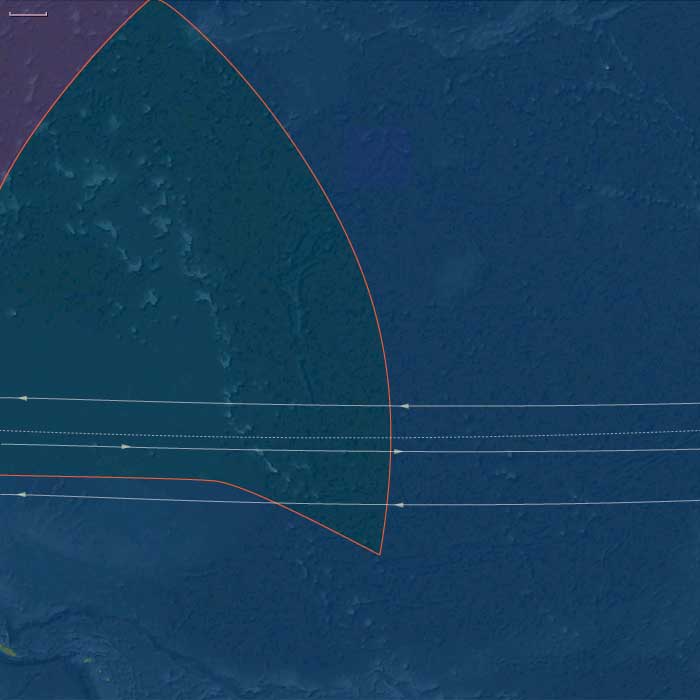

The subregion of East Micronesia includes the Marshall Islands, the Caroline Islands (including Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei, and Kosrae), and Kiribati’s eastern groups. This vast maritime expanse was composed of low-lying coral atolls, scattered reef islands, and high volcanic islands rising from the Pacific floor. Narrow reef passes, expansive lagoons, and coastal mangroves framed settlement zones, while interior volcanic slopes on Pohnpei and Kosrae provided fertile agricultural land.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

This age coincided with the onset of the Little Ice Age, when subtle cooling across the Pacific produced shifts in rainfall and sea-surface temperatures. Atolls were most vulnerable: prolonged droughts threatened freshwater lenses and coconut groves. El Niño and La Niña cycles brought alternating stress—either drought or torrential rains—that forced adaptive responses. High volcanic islands moderated these extremes with rivers and fertile soils, sustaining denser populations.

Subsistence & Settlement

Communities thrived through diversified subsistence. On high islands, taro, yam, breadfruit, and banana cultivation supported permanent settlements. On atolls, reliance fell on coconut palms, pandanus, breadfruit groves, and lagoon fisheries. Settlements clustered around lagoons and coastal plains, with stilt houses and canoe houses serving as central features. Pigs and chickens supplemented diets, while exchange of surplus foods reinforced political alliances. Populations were concentrated on fertile volcanic islands like Pohnpei and Kosrae, but atoll communities were integrated into larger networks through voyaging.

Technology & Material Culture

This age saw the height of Micronesian navigational mastery. Star compasses, swell patterns, cloud formations, and bird flights guided double-hulled or outrigger canoes across thousands of kilometers. Monumental stone constructions on high islands, particularly the city of Nan Madol on Pohnpei, expressed political centralization and ritual authority through vast basalt platforms and canals. Stone adzes, shell ornaments, woven mats, and decorated canoes formed the material foundation of everyday life and ceremonial exchange.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

East Micronesia’s identity was defined by its voyaging corridors. Navigators linked atolls with volcanic centers, ensuring the flow of food, mats, ornaments, and ritual specialists. Yap’s influence extended eastward through tribute and exchange systems, while Pohnpei and Kosrae hosted complex chiefdoms. Eastward links reached into the Marshalls, where stick charts encoded navigational knowledge for inter-island voyages. Though Europeans had not yet entered, Micronesians maintained a maritime world connected by sophisticated and reliable sea routes.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Genealogies and oral traditions linked rulers to ancestral spirits and gods. On Pohnpei and Kosrae, monumental centers like Nan Madol embodied sacred kingship, serving as both ritual spaces and symbols of chiefly power. Navigational knowledge was sacred, guarded by specialists who transmitted it orally in ritualized training. Ritual exchanges of food and mats reinforced alliances; ceremonies involving breadfruit and kava integrated agriculture with cosmic order.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Communities displayed resilience to climatic fluctuations through diversified strategies. Atoll dwellers relied on coconut and pandanus groves, drought-resistant and crucial for survival. Inter-island voyaging allowed the redistribution of surplus food during shortages, while tribute systems balanced ecological variability. Irrigated taro terraces and breadfruit groves on high islands buffered against crop failure. Collective rituals of exchange and redistribution reinforced social resilience as much as ecological.

Transition

By 1539 CE, East Micronesia stood as a maritime network of navigators, farmers, and builders. Monumental centers, voyaging canoes, and tribute systems bound together atolls and volcanic islands into an integrated cultural sphere. Europeans had not yet disrupted these patterns, but the region’s navigational expertise and hierarchical chiefdoms made it a dynamic center of Pacific history, prepared to both endure and adapt to the encounters soon to come.

Groups

Topics

Commodoties

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 43406 total

Northeastern Eurasia (1396–1539 CE): Little Ice Age Rim — Ice Roads, Salmon Corridors, and Steppe–Forest Frontiers

Geographic & Environmental Context

Northeastern Eurasia was not one land but three adjoining worlds stitched together by rivers, coasts, and winter ice:

-

Northeast Asia — the Lena–Indigirka–Kolyma taiga–tundra, the Chukchi–Anadyr coast and Wrangel, the Sea of Okhotsk rim with the Amur–Ussuri lowlands, Sakhalin, and (Ezo) Hokkaidō.

-

Northwest Asia — western/central Siberia from the Urals to the Altai, spanning Ob–Irtysh–Yenisei basins, taiga belts, and steppe margins.

-

East Europe — the Baltic–Dvina/Vistula watersheds through the Dnieper–Don–Oka–Volga to the Ural forelands, where forest, forest-steppe, and the Pontic steppe overlapped.

These worlds were more tightly coupled to their external neighbors (the Pacific, Central Asia, the Black/Baltic Seas) than to each other—precisely the pattern The Twelve Worlds expects.

Climate & Environmental Shifts (Little Ice Age)

Longer winters, deeper sea ice, and shorter growing seasons defined the rim:

-

Bering/Okhotsk: thicker seasonal pack ice and stormier belts along Anadyr/Okhotsk; river freeze-up lengthened overland mobility but narrowed spring fish windows.

-

Siberian interior: permafrost pushed south; river ice lingered into late spring; summer flood pulses swelled the Ob–Irtysh–Yenisei.

-

East European steppe rim: drought–flood oscillations heightened vulnerability to Crimean and Nogai raids.

Households hedged risk with storage (smoked fish/meat, oils), multi-site settlement (winter river nodes / summer dispersed camps), and diversified ecologies (coast–river–upland rotations).

Lifeways & Polities

Northeast Asia

-

Subsistence: Coastal whale–walrus–seal hunting (Chukchi, maritime Even), inland reindeer hunting/herding(Chukchi, Even/Evenki, Yukaghir); salmon–sturgeon civilizations along the Amur–Ussuri–Sakhalin (Daur, Nanai/Hezhe, Udege, Nivkh); Ainu river–coast salmon/deer/bear regimes in Hokkaidō with hardy field plots and acorn processing.

-

Society: Village storehouses, fish weirs, smokehouses; dogsleds, skis, birch-bark/plank boats. Iron knives/pots moved in via interregional barter; lacquer/imports appeared at contact nodes.

-

Politics: No intrusive agrarian states; authority nested in clans, ritual specialists, and river alliances.

Northwest Asia

-

Subsistence: Turkic/Mongol herders on steppe margins; Ob-Ugric, Samoyedic, Yeniseian hunters/fishers in taiga–tundra; mixed agro-pastoralism in Altai valleys; Nenets reindeer management on the Arctic fringe.

-

Power: The Siberian Khanate (Irtysh–Tyumen) levied furs/slaves; Kazan and Nogai raided and mediated caravan trade; no Muscovite crossing of the Urals yet—that comes next epoch.

East Europe

-

Economy: Forest honey/wax/furs; black-earth grain; saltworks and iron; Baltic grain via Vistula–Gdańsk.

-

Power shifts: Muscovy rose (annexed Novgorod 1478, Pskov 1510, ended Horde tribute 1480); Lithuania-Rus’ reached its zenith then bled in wars with Muscovy (loss of Smolensk 1514); Crimea (Ottoman 1475)dominated the Black Sea littoral; Ducal Prussia 1525 stabilized Poland’s Baltic flank.

Economy & Exchange

-

Northeast Asia: Salmon, oils, skins, and dried fish moved along riverine/ice corridors; Nivkh pilots ferried goods across Sakhalin straits; Ainu exchanged furs/fish for iron and prestige items via gray-zone ties to Wajin outposts.

-

Northwest Asia: Fur frontiers flowed south to Kazan/Bukhara; textiles, grain, and iron went north; caravan trails spanned steppe corridors; river canoes threaded the Ob/Yenisei.

-

East Europe: Hanse/Baltic pulled forest goods west; Oka–Volga bound Muscovy’s service state; Dnieper constrained by Crimean–Ottoman control; early Cossack prototypes appeared in lower marshlands.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Arctic–Subarctic: toggling harpoons, sinew-backed bows, dog traction, skis, raised granaries; birch-bark craft and plank boats; fish weirs and wicker traps.

-

Steppe–Taiga: yurts/felt tents; sledges and ski-shoes; birchbark containers; small-scale smithing; fur robes and ritual regalia (drums, antler headdresses).

-

East Europe: gunpowder siege tools enter; brick/stone kremlins (Italian-engineered walls/cathedrals in Moscow); chancery codes—Sudebnik (1497) in Muscovy, Lithuanian Statute (1529); Ruthenian printing (Skaryna, 1517–25).

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Ice roads & frozen rivers: winter highways across Lena–Aldan–Indigirka–Kolyma and Anadyr; long-haul sled caravans between steppe and forest.

-

Amur trunk: salmon polities brokered taiga–coast exchange and linked south toward Manchuria.

-

Okhotsk littoral & straits: seasonal ferrying by Nivkh pilots; canoe arcs along Hokkaidō to the southern Kurils.

-

Steppe corridors: khanate caravans drew furs/slaves into the Kazan–Bukhara zone; raiding and tribute overlapped with trade.

-

East European rivers: Vistula to the Baltic; Oka–Volga for Muscovite assembly and frontier watches; Carpathian passes for salt/wine/cattle.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Shamanic cosmologies (Evenki, Yukaghir, Chukchi, Nivkh): drum rites, trance, helping spirits; place-spirits sacralized salmon riffles, rookeries, and passes.

-

Ainu ritual life: iomante (bear-sending), carved prayer sticks (ikupasuy), shaved-wood inau offerings, tattooing in parts of Hokkaidō.

-

Turkic epics and Islamic court culture in steppe towns; forest peoples’ clan dances, antler offerings, and river shrines.

-

Orthodox East Europe: icon schools (Rublev’s legacy), monastic federations (Trinity–Sergius), “Third Rome” idioms after Ivan III–Sophia Palaiologina marriage; Ruthenian confraternities sustained schools/charities.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Caching & rotation: multi-year fish weirs, rotational traplines, and stored oils/fats buffered scarcity.

-

Mobility: reindeer and dog traction extended winter range; dual-site settlement (winter rivers / summer camps) spread risk; steppe herders shifted pastures with snowpack and drought.

-

Siting: raised granaries and flood-savvy village plans along Amur; fortified monasteries and watch-lines in East Europe; clan reciprocity smoothed shocks across ecotones.

Subregional Signatures (in one glance)

-

Northeast Asia: ice margins + salmon corridors—indigenous river–sea civilizations with limited iron inflows, no imperial intrusion.

-

Northwest Asia: khanates + forest worlds—fur tribute and caravan war/peace systems, Siberian Khanate ascendant, Muscovy not yet over the Urals.

-

East Europe: gathering of states—Muscovy’s consolidation; Lithuania-Rus’ codification and contraction; Crimean–Ottoman Black Sea dominance; Baltic grain arteries.

Each subregion aligned as much with its far neighbors (Pacific fisheries, Central Asian caravans, Ottoman Black Sea) as with one another—confirming The Twelve Worlds argument that regions are envelopes; subregions are the living units.

Transition by 1539

The template was set for the next century’s upheavals:

-

Northeast Asia remained an indigenous archipelago of ice roads and salmon states, soon to face southern and western state pressures.

-

Northwest Asia balanced khanate tribute and forest autonomy; Muscovy stood just beyond the Urals, poised for the Siberian push.

-

East Europe entered confessional and imperial realignments with a centralized Muscovy, embattled Lithuania-Rus’, and an Ottoman-Crimean Black Sea.

Across the rim, ice, river, and steppe still governed movement—but by the mid-sixteenth century the age of states would ride those same corridors.

Northeast Asia (1396–1539 CE): Ice Margins, Salmon Corridors, and River–Sea Worlds

Geography & Environmental Context

Northeast Asia comprises the Lena–Indigirka–Kolyma basins and New Siberian Islands; the Chukchi Peninsula, Wrangel Island, and the Anadyr basin; the Sea of Okhotsk rim from Magadan to Okhotsk with the Uda–Amur–Ussuri lowlands (including extreme northeastern Heilongjiang); the Sikhote–Alin and Primorye uplands (upper half); Sakhalin and the lower Amur mouth; and Hokkaidō (except its southwestern corner). Anchors: permafrosted taiga–tundra north of the tree line; ice-prone Bering and Okhotsk coasts; salmon rivers descending the Sikhote–Alin; and oak–birch forests across Hokkaidō.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The early Little Ice Age brought longer winters, deeper sea ice in the Bering/Okhotsk seas, and shorter growing seasons on Hokkaidō. River freeze-up extended overland mobility but squeezed spring runs and travel windows. Storm belts intensified along the Anadyr and Okhotsk coasts; interior permafrost thickened, stabilizing winter “roads” while complicating warm-season portage.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

High Arctic & Chukchi–Anadyr: Marine hunting (whale, walrus, seal) on the coasts; inland reindeer hunting and small-scale herding among Chukchi, Even, and Yukaghir groups.

-

Lena–Indigirka–Kolyma taiga: Evenki/Even/Yukaghir mixed economies of fishing, ungulate hunting, trapping; seasonal camps arrayed along river terraces.

-

Amur–Ussuri–Sakhalin: Daur, Nanai (Hezhe), Udege, and Nivkh villages centered on salmon, sturgeon, millet/legumes, with stilted storehouses and smokehouses.

-

Hokkaidō (Ezo): Ainu coastal and river settlements focused on salmon, deer, bear, and marine harvests; small fields of hardy crops supplemented stored fish and acorns.

Technology & Material Culture

Composite bows; toggling harpoons; sinew-backed arrows; winter dog sleds and skis; birch-bark/plank boats for open water. Fish weirs, wicker traps, drying racks, and oil rendering were ubiquitous. In the Amur–Hokkaidō arc, iron knives and pots circulated via interregional trade; Ainu ritual implements—ikupasuy (prayer sticks) and inau (wood-shaved offerings)—figured prominently. Ornaments in bone/antler, carved wooden dishes, and lacquer imports at contact nodes signaled status.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Frozen rivers as highways: Winter travel stitched together the Lena–Aldan–Indigirka–Kolyma systems and the Anadyr corridor.

-

Amur trunk: Salmon villages mediated taiga–coast exchange and linked southward toward Manchuria.

-

Okhotsk littoral & Sakhalin straits: Nivkh pilots ferried goods seasonally.

-

Hokkaidō coast: Canoe routes tied Ishikari–Tokachi–Nemuro; crossings reached the southern Kurils. Long-distance ties with Wajin (Japanese) were episodic and indirect in this era.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Shamanic cosmologies (drum rites, trance, helping spirits) guided Evenki, Yukaghir, Chukchi, and Nivkh ritual life. Among the Ainu, seasonal rites culminated in the bear-sending ceremony, iomante, returning the bear’s spirit to the divine realm. Place-spirits sacralized salmon riffles, seal rookeries, and mountain passes. Carved masks, beadwork, tattooing (in parts of Hokkaidō), and story-singing preserved lineages and territorial memory.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Caching (smoked salmon, rendered oils, dried meat), multi-year net/weir regimes, and rotational hunting grounds buffered variability. Reindeer and dog traction extended mobility; settlement duality (winter riverine nodes / summer dispersed camps) spread risk. Along the Amur, raised granaries and flood-aware siting reduced losses. On Hokkaidō, acorn processing and herring pulses complemented salmon cycles.

Transition

By 1539, Northeast Asia remained an indigenous archipelago of river routes and sea-ice margins. Trade threads brought limited iron and prestige goods into Amur–Hokkaidō circuits, but political intrusion from agrarian empires was still distant. The ecological template—ice roads, salmon corridors, and taiga hunting—set the stage for later encounters with state powers pressing in from the west and south.

Northern North America (1396–1539 CE)

Forests, Rivers, and the Last Age of Independent Worlds

Geography & Environmental Framework

From the glacier-fed fjords of Alaska and the rainforests of British Columbia to the hardwood valleys of the Great Lakes and the wetlands of the Gulf Coast, Northern North America in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries was a continent of immense ecological variety. The region encompassed the salmon-rich Pacific coasts and interior plateaus, the maize fields and forest clearings of the East, and the arid basins, pueblos, and oak woodlands of the far West.

The Little Ice Age deepened climatic contrasts. Glaciers advanced along the St. Elias and Alaska ranges; sea ice thickened around Greenland and Hudson Bay; drought and flood cycles alternated along the Mississippi, Rio Grande, and Colorado. Storms battered the Atlantic littoral while upwelling currents nourished fisheries on the Pacific. Yet Indigenous societies—adapted to every biome—met these shifts with remarkable resilience, creating a tapestry of ecological adaptation that bound the continent together long before sustained European contact.

Northwestern North America: Coastal Riches and Interior Pathways

Geography & Environmental Context

Stretching from Alaska and the Yukon southward through British Columbia and Washington into northern Oregon, this subregion blended fjorded coastlines, dense cedar forests, salmon-bearing rivers, and sub-Arctic tundra uplands. The Columbia River and the Inside Passage provided natural corridors linking ocean and interior.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

During the early Little Ice Age, glacial tongues advanced in the coastal ranges, and colder seas shortened salmon runs. Intense winter storms alternated with mild decades of recovery. Inland, cooler summers limited wild plant productivity, but trade and storage stabilized food systems.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Coastal nations—Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Nuu-chah-nulth, and Coast Salish—built cedar plankhouses in sheltered bays, fished salmon, halibut, and cod, hunted whales and seals, and gathered berries and roots. The potlatch ceremony redistributed wealth and validated status.

-

Interior and plateau groups—Nez Perce, Carrier, Sekani, Shoshone—followed cyclical routes of fishing, root gathering, and elk and deer hunting, converging at river crossings for trade and ceremony.

-

In the Aleutians, Unangan hunters in semi-subterranean barabaras pursued sea mammals in agile baidarkas.

Technology & Material Culture

Cedar woodworking produced monumental canoes, totem poles, bentwood boxes, and masks that embodied ancestral and animal spirits. Stone adzes, bone fishhooks, and antler harpoons reflected technological mastery. Snowshoes, sledges, and skin clothing extended mobility into icy interiors.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The Inside Passage knit coastal societies into a maritime world of exchange in fish oil, copper, and shell ornaments. The Columbia River linked inland fishing villages to coastal trade, while Aleutian straits connected Alaska with Siberia through small-scale barter networks.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Raven and Thunderbird myths recounted creation and transformation. Totemic carvings displayed clan ancestry; the potlatch dramatized social law and cosmic balance. Shamanic healing and trance rituals bound communities to land, water, and animal spirits.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Communities relied on smoking and drying salmon, storing oil, and seasonal migration between rivers and forests. Trade redistributed surpluses across ecological zones. Ceremony reinforced stewardship, ensuring balance between people and the natural world.

Transition

By 1539 CE, the Pacific Northwest and sub-Arctic were densely peopled, self-governing regions untouched by Europe. Glaciers and seas defined life, and the rhythm of salmon and ceremony shaped civilizations thriving in isolation.

Northeastern North America: Woodland Societies and First Atlantic Glimpses

Geography & Environmental Context

This subregion extended from Florida to Greenland, encompassing the Appalachians, St. Lawrence, Great Lakes, and Hudson Bay. Temperate forests merged with boreal shield and tundra, forming one of the most ecologically varied landscapes on Earth.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Little Ice Age brought long winters and shortened growing seasons. Snowpack lingered on uplands; Atlantic storms reshaped barrier coasts; northern ice thickened across Greenland and Labrador. Despite harsher conditions, forest and aquatic productivity supported dense and enduring populations.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Iroquoian and Algonquian farmers cultivated maize, beans, and squash in fertile river valleys, supplementing with hunting and fishing. Longhouse villages and fortified palisades dotted the Finger Lakes and St. Lawrencevalleys.

-

Great Lakes peoples managed fisheries and engaged in extensive copper and shell trade.

-

Canadian Shield hunters followed caribou, moose, and fish, practicing seasonal mobility.

-

Inuit Thule communities in Greenland and Labrador expanded dog-sled and umiak travel, perfecting seal and whale hunting.

-

Bermuda remained uninhabited, a sanctuary for seabirds and turtles.

Technology & Material Culture

Birchbark canoes, dugouts, snowshoes, bows, and polished stone tools enabled adaptation to forest and river. Wampum belts recorded treaties and myth; pottery, textiles, and copper ornaments expressed artistry. Inuit toggling harpoons, bone goggles, and tailored skins exemplified Arctic ingenuity.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Canoe routes along the St. Lawrence, Great Lakes, and Mississippi bound distant polities in trade and diplomacy. Coastal peoples navigated estuaries for fishing and exchange. Inuit crossed sea-ice to Baffin Island and Labrador, maintaining circumpolar networks.

By the early sixteenth century, Portuguese, Basque, and Breton fishers anchored off Newfoundland, harvesting cod and whale oil—fleeting contact without conquest.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Woodland cosmologies envisioned spirits in animals, rivers, and maize. Shamans mediated between visible and invisible realms; ceremonies of planting, hunting, and mourning affirmed communal balance. Wampum diplomacy symbolized alliances, while Inuit storytelling, drumming, and carving honored sea spirits and ancestors.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Intercropped maize fields, stored surpluses, and hunting cycles buffered scarcity. Wild rice and maple sugar enriched northern diets. Inuit adapted to extreme cold through fuel-efficient dwellings and clothing design. Cooperation ensured survival through climatic volatility.

Transition

By 1539 CE, northeastern societies remained autonomous. Europe’s presence was limited to cod fleets and mapmakers. The vast woodlands, lakes, and tundra still belonged to their Indigenous custodians.

Northwestern North America (1396–1539 CE)

Coastal Riches and Interior Pathways

Geography & Environmental Context

This subregion stretched from Alaska and the Yukon south through British Columbia and Washington, extending inland to the Rockies and the Columbia River. A rugged world of fjords, salmon rivers, conifer forests, and tundra valleys sustained dense coastal populations and far-ranging interior hunters.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Little Ice Age advanced glaciers in the St. Elias Mountains and shortened growing seasons inland. Stronger coastal storms and variable salmon runs tested food systems, but abundant rainfall kept forests lush.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Coastal nations—Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Nuu-chah-nulth, Coast Salish—built cedar plankhouses, fished salmon and halibut, hunted sea mammals, and gathered berries. The potlatch ceremony reaffirmed hierarchy and reciprocity.

-

Interior and plateau peoples—Nez Perce, Carrier, Kaska, Sekani, Shoshone—followed seasonal rounds of fishing, hunting elk and caribou, and gathering roots such as camas and wapato.

-

Aleut (Unangan) in the Aleutians lived in semi-subterranean barabaras and hunted seals, sea otters, and whales from agile baidarkas.

Technology & Material Culture

Cedar canoes, bentwood boxes, and carved masks embodied cosmology and clan identity. Stone, bone, and antler tools served hunting and woodworking; snowshoes and sledges sustained inland travel. The Aleut perfected composite harpoons and waterproof skin parkas for open-sea hunting.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The Inside Passage supported trade in fish oil, copper, and shells. The Columbia River linked coast and plateau. Mountain passes ferried obsidian and hides, while the Aleutian straits connected Alaska to Siberia through limited barter.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Raven and Thunderbird myths dramatized creation and transformation. Clan crests, totems, and potlatch exchanges articulated law, kinship, and spirituality. Inland, shamanic vision quests and mountain veneration affirmed ties to the landscape.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Smoking and drying salmon, oil preservation, and inter-village trade buffered scarcity. Mobility between river valleys and coast distributed risk. Despite climatic volatility, abundance endured through cooperation and ceremony.

Transition

By 1539 CE, the Pacific Northwest was a thriving Indigenous maritime world. No sustained European presence had yet appeared; only distant rumors of ships in the southern seas hinted at change.

Polynesia (1396–1539 CE)

Ahupuaʻa Landscapes, Interisland Canoes, and Sacred Leeward Seas

Geography & Environmental Context

Polynesia in this age formed a triad of enduring worlds: North Polynesia (the Hawaiian chain except Hawai‘i Island, plus Midway Atoll), West Polynesia (Hawai‘i Island, Samoa, Tonga, Tuvalu, Tokelau, the Cook Islands, and French Polynesia—Tahiti, the Society, Tuamotu, and Marquesas Islands), and East Polynesia (Rapa Nui and the Pitcairn group).

Volcanic high islands—O‘ahu, Maui, Tahiti, Savai‘i, and Hawai‘i—framed fertile valleys and alluvial plains; coral atolls—Tuvalu, Tokelau, parts of the Cooks and Tuamotus—offered thin soils and fragile freshwater lenses; far to the east, Rapa Nui and Henderson stood as remote outliers where stone and sea set strict limits on life.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

Within the Little Ice Age, conditions trended slightly cooler with episodic droughts and intensified winter rains. High islands captured orographic moisture that fed irrigated systems, while leeward slopes and atolls felt drought stress most acutely. Cyclones periodically raked the central and western archipelagos; powerful swells and storms reworked beaches, loko iʻa fishpond walls, and atoll shorelines. Offshore, cooler seas nudged fish migrations and seasonality.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

High islands (Hawai‘i, Tahiti, Samoa, Marquesas):

Intensive irrigated taro (loʻi) in valley bottoms paired with extensive dryland sweet-potato field systems on leeward slopes.

Along coasts, engineered fishponds stabilized protein supply, especially on O‘ahu, Moloka‘i, and Hawai‘i.

Dense villages clustered around chiefly centers, heiau/marae precincts, and irrigated landscapes. -

Atolls (Tuvalu, Tokelau, parts of Cooks/Tuamotus):

Pulaka pits sunk into freshwater lenses, coconuts, breadfruit, and lagoon fisheries underpinned smaller, more vulnerable populations. -

Eastern frontier (Rapa Nui & Pitcairn group):

Rapa Nui sustained rock-mulched gardens (sweet potato, yams), chicken husbandry, and nearshore fishing while monumental ahu–moai construction crested; Pitcairn and Henderson supported small, intermittent settlements balancing gardens, reef harvests, and seabirding.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Canoe mastery: Double-hulled voyaging canoes linked islands across hundreds of kilometers; outriggers worked lagoons and channels.

-

Landscape engineering: Basalt adzes cut terraces, irrigation ditches, and monumental platforms; dryland field alignments and mulches buffered aridity; coastal loko iʻa exemplified hydrological skill.

-

Prestige arts: Feather cloaks and helmets (Hawai‘i), finely woven mats (ʻie tōga) and kava regalia (Tonga / Samoa), tattooing (Marquesas, Tahiti), painted tapa, and carved deity images encoded rank, genealogy, and cosmology.

-

Rapa Nui’s quarrying and transport of moai showcased coordinated labor and ritual engineering in a resource-tight setting.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Intra-archipelago circuits:

-

Hawai‘i: Inter-island rivalries and exchanges moved tribute, surplus, and warriors across channels; Moloka‘i retained renown as a spiritual and diplomatic center.

-

Tonga–Samoa–ʻUvea / Fiji: Marriage, kava ceremony, and tribute radiated Tongan influence while Samoa remained a cultural hearth.

-

Tahiti–Tuamotus–Cooks–Marquesas: Society Islands rose as ritual and exchange hubs binding east and west.

-

-

Peripheral links: Midway remained marginal in Hawaiian awareness; Pitcairn–Henderson–Ducie–Oenomaintained intermittent resource voyaging.

Long-distance voyaging beyond the Polynesian core had largely ceased, leaving each sphere internally networked yet regionally distinct—and still untouched by Europe in this period.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Ritual sovereignty: Kapu / tapu systems ordered access to land, sea, labor, and gendered spaces; seasonal rites (e.g., Makahiki tied to Makali‘i / Pleiades) synchronized agriculture and polity.

-

Temple landscapes: Heiau (Hawai‘i) to marae (Tahiti) anchored offerings to Kū, Lono, ʻOro, and lineage gods; red-feather regalia (maro ʻura) consecrated paramounts.

-

Genealogical chant & body: Mele, oratory, and tattoo embodied ancestry and divine descent; in Rapa Nui, the evolving tangata manu (bird-man) cult shifted power to seasonal ritual contests at Orongo.

-

Exchange as theatre: Ceremonial gifting—ʻie tōga, pigs, red feathers—materialized hierarchy and alliance across lagoons and channels.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Hydro-ecological balance: Irrigation captured steep-valley flows; dryland grids with stone mulches stabilized yields; fishponds buffered marine variability.

-

Atoll ingenuity: Pulaka pits, coconut silviculture, and reef tenure sustained life on thin soils; kin networks redistributed food after storms.

-

Eastern edge: Lithic mulching, windbreaks, and intensified poultry compensated for timber scarcity on Rapa Nui; Pitcairn / Henderson scaled settlement to water constraints.

-

Political redistribution: Tribute and chiefly feasting moved surpluses from fertile districts to deficit zones, embedding resilience in hierarchy.

Transition (to 1539 CE)

Between 1396 and 1539 CE, Polynesia achieved a mature equilibrium of agricultural intensification, aquaculture, and ritual centralization. Hawaiian fishpond states and kapu-ordered landscapes, Tongan–Samoan voyaging chiefdoms and kava diplomacy, Tahiti–Marquesas monumental and tattooed polities, and Rapa Nui’s ahu–moai cosmos each expressed a shared oceanic grammar adapted to local ecologies.

No European sails had yet altered these systems, but population density, inter-island rivalries, and climatic pulses demanded careful management. The social and engineering frameworks perfected in this age would be the very strengths—and points of stress—poised to meet the profound disruptions of the centuries ahead.

North Polynesia (1396–1539 CE): Ahupuaʻa Landscapes, Interisland Canoes, and Sacred Leeward Seas

Geographic & Environmental Context

The subregion of North Polynesia includes the high Hawaiian Islands of Kaua‘i, Ni‘ihau, O‘ahu, Moloka‘i, Lāna‘i, Kaho‘olawe, and Maui; the chain of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands from Nihoa to Kure; and Midway Atoll. Anchors span windward volcanic ranges with deep stream valleys (Kaua‘i, O‘ahu, Maui), leeward dry slopes and lava plains (Moloka‘i, Lāna‘i, Kaho‘olawe), salt pans and coastal flats (Ni‘ihau), and low coral atolls to the northwest hosting vast seabird rookeries and monk seal haul-outs. Reef-lined embayments, interisland channels, and the Kuroshio/NE trade-wind regime knit the archipelago into one oceanic world.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Little Ice Age introduced slightly cooler sea-surface temperatures and heightened interannual variability.

-

Windward slopes: orographic rains remained reliable, feeding perennial streams and valley wetlands.

-

Leeward zones: experienced longer dry spells; periodic Kona storms brought intense winter rains.

-

Northwestern atolls: exposed to winter swell and cyclones, yet sustained by productive upwelling. ENSO events modulated rainfall and hurricane risk, intermittently stressing dryland field systems and coastal fisheries.

Subsistence & Settlement

Island communities organized land and sea within ahupuaʻa—mauka-to-makai districts integrating upland forests, irrigated valleys, and reefs.

-

Irrigated kalo (taro) systems: loʻi terraces and ʻauwai canals filled stream valleys on O‘ahu (Kāne‘ohe, Nuʻuanu), Kaua‘i (Hanalei, Wainiha), Moloka‘i’s wet windward gulches, and east Maui.

-

Dryland field systems: leeward slopes on O‘ahu, Maui, Moloka‘i, Lāna‘i, and Kahoʻolawe supported intensive ʻuala (sweet potato), kō (sugarcane), and gourd complexes built with stone mulch, windbreaks, and contour alignments.

-

Coastal fisheries: nearshore netting and hook-and-line, reef gleaning, and stone-walled fishponds (loko iʻa) around O‘ahu and Moloka‘i provided steady protein and storage.

-

Niʻihau & the NWHI: Niʻihau specialized in salt and nearshore fishing; the Northwestern chain and Midway were uninhabited but visited episodically for birds, feathers, fish, and ritual purposes.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Agricultural engineering: terraced loʻi, earthen/stone dikes, and diversion ʻauwai; dryland alignments and mulch beds moderated heat and wind.

-

Maritime craft: double-hulled voyaging canoes (waʻa kaulua), outrigger fishing canoes, bone/pearl-shell fishhooks, sennit lashings, and sail rigs tuned to trades and channels.

-

Tools & textiles: basalt adzes, wooden digging sticks, fiber cordage; barkcloth (kapa), feather capes (ʻahu ʻula) and helmets (mahiole) for chiefly display.

-

Architecture & ritual: coastal and upland heiau (luakini war temples, agricultural heiau), house platforms, canoe sheds, and fishpond walls of fitted stone.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Interisland canoe routes: linked valleys, fishpond districts, and forest bird-feather grounds; channels between O‘ahu–Moloka‘i–Lāna‘i–Maui formed a busy maritime hub.

-

Resource circuits: salt from Niʻihau, bird feathers from Nihoa/Mokumanamana, basalt and timber from selected valleys, and prized fish from pond complexes circulated through chiefly exchange.

-

Seasonal ranging: expeditions to the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and Midway occurred for birding, fishing, and rites; these low isles functioned as waymarks and sacred limits of the archipelago.

Long-distance trans-Polynesian voyaging had largely waned by this age, but sophisticated wayfinding underpinned interisland travel and provisioning.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Political life centered on aliʻi (chiefly) lineages under the kapu system that governed access to land, labor, and ritual.

-

Ritual cycle: offerings at heiau coordinated planting, fishing closures, and warfare; the Makahiki festival renewed abundance under the god Lono.

-

Landscape of meaning: ahupuaʻa altars at district boundaries, fishpond shrines, and upland forest taboos inscribed stewardship into space.

-

Arts: formal chant (oli), hula, and oratory framed genealogies and chiefly deeds; featherwork regalia and fine kapa signaled rank.

-

Northwestern isles: kupuna (ancestral) associations and bird-sending rites marked these remote atolls as spiritually potent, even without permanent settlement.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Diversified agro-seascapes: coupling irrigated kalo with leeward ʻuala fields and loko iʻa buffered drought and storm.

-

Fisheries management: kapu closures by season or lunar phase protected spawning runs; fishponds converted pulses of juvenile fish into reliable stores.

-

Water & wind engineering: ʻauwai maintenance, terrace repairs, windbreaks, and stone mulches stabilized yields; upland replanting and forest kapu protected springs.

-

Risk-spreading mobility: interisland canoeing redistributed food and labor after crop failures or storms; expeditions to bird-rich NWHI supplemented protein and ornament demand.

Technology & Power Shifts (Conflict Dynamics)

Chiefly competition waxed and waned among island polities (O‘ahu, Maui, Kaua‘i, Moloka‘i), with alliances, marriage ties, and warfare legitimized through heiau luakini rites. Control of fishpond districts, irrigated valleys, and leeward field systems conferred power. Ritual specialists enforced kapu on land and sea; victory and redistribution feasts reinforced allegiance. No external powers intruded during this age.

Transition

By 1539 CE, North Polynesia was a tightly integrated ahupuaʻa commonwealth—hydraulic valleys feeding ponded coasts, dryland mosaics supplying staples, and interisland canoes knitting the system together. The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and Midway remained unpeopled sanctuaries and waymarks, visited but not settled. Chiefly rivalries, ritual governance, and careful ecological management sustained abundance on the eve of a wider Pacific world that, in later centuries, would test these island balances.

The Maori tribes are fully established in New Zealand's two large islands before the fourteenth century, by which time most of Oceania’s autocthonous inhabitants are in place.

West Polynesia (1396–1539 CE): Voyaging Chiefdoms in an Oceanic Constellation

Geographic & Environmental Context

The subregion of West Polynesia includes the Big Island of Hawaii, Samoa, Tonga, Tuvalu, Tokelau, the Cook Islands, and French Polynesia. This vast expanse of the Pacific encompassed volcanic high islands with fertile soils (Hawai‘i, Samoa, Tonga), low-lying atolls (Tuvalu, Tokelau), and the scattered archipelagos of the Cook and French Polynesian chains, where coral reefs and lagoons framed ocean-facing coasts. Rugged mountains, fertile valleys, and reef-fringed shorelines created a mosaic of ecological niches tied together by open-sea voyaging routes.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

This age unfolded during the early centuries of the Little Ice Age, when modest global cooling affected rainfall and sea-surface temperatures. In West Polynesia, conditions translated into slightly more variable rainfall and occasional prolonged droughts, especially on atolls with thin soils and no freshwater streams. ENSO (El Niño–Southern Oscillation) cycles periodically intensified storms, disrupting agriculture and altering fish stocks. Despite these fluctuations, the overall climate remained warm and suitable for cultivation and seafaring.

Subsistence & Settlement

By this period, societies across West Polynesia were well established and populous. Settlements clustered along fertile valleys, reef-protected bays, and coastal plains. Taro terraces, irrigated in Hawai‘i and Samoa, sustained dense populations, while breadfruit groves, banana stands, and yam fields provided staples on volcanic islands. Atolls depended on coconut palms, pandanus, breadfruit, and lagoon fisheries. Pigs, chickens, and dogs were widespread, integrated into feasting economies and ritual life. Canoe-fishing sustained communities across reef and pelagic zones, targeting tuna, bonito, and reef fish with hook-and-line, nets, and trolling gear.

Technology & Material Culture

This was the height of Polynesian seafaring and technological adaptation. Double-hulled canoes with woven sails carried chiefs, priests, and explorers across vast distances, maintaining networks among scattered archipelagos. Houses were built from timber, pandanus thatch, and basalt stone, while monumental architecture—temples (marae/heiau)—marked religious and political centers, particularly in the Societies, Cooks, and Hawai‘i. Stone adzes, shell ornaments, barkcloth textiles, and finely worked wooden implements displayed skilled craftsmanship. Ritual and political authority was reinforced through monumental constructions and the symbolic power of material goods.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

West Polynesia was knit together by ocean corridors. Navigators used stars, swells, cloud formations, and bird flights to guide voyaging canoes between Samoa, Tonga, Fiji, and further east into the Cooks and French Polynesia. These routes sustained tribute, marriage alliances, and religious exchange. The Tongan maritime chiefdom maintained networks of influence stretching into Samoa and Fiji. Hawaiian voyaging also linked the islands internally, reinforcing political unification trends. Though external contact with Europeans had not yet begun, Polynesians were active shapers of their own maritime world.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

This age was marked by the flourishing of chiefly ritual systems and religious traditions. Sacred spaces—marae and heiau—were centers of worship and political authority. Genealogies connected ruling chiefs to gods and ancestors, legitimizing hierarchy and tribute systems. Ceremonial exchanges of food, barkcloth, and ornaments reinforced kinship ties across archipelagos. Oral traditions—chants, genealogies, mythic histories—preserved collective memory and cosmic order. Symbols of authority, such as feathered cloaks in Hawai‘i or kava rituals in Tonga and Samoa, expressed both spiritual and political power.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Communities displayed remarkable resilience to environmental variability. On atolls, water scarcity was managed by rainwater collection and coconut-based subsistence systems. Diversified agriculture on high islands buffered against crop failures; irrigation systems in Hawai‘i and Samoa ensured food security during droughts. Social systems of redistribution—tribute, feasting, and ceremonial exchange—spread risk across lineages and islands. Voyaging itself was a form of resilience, connecting resource-poor islands to richer neighbors.

Transition

By 1539 CE, West Polynesia stood as a constellation of powerful, interconnected chiefdoms. Monumental architecture, sophisticated agriculture, and advanced voyaging maintained social and ecological balance across a dispersed maritime world. Though European contact was still decades away, the structures of resilience, ritual, and inter-island exchange ensured that West Polynesia was already a dynamic and integrated system at the heart of the Pacific.

Micronesia (1396–1539 CE)

Navigational Networks, Monumental Islands, and the Star Compass World

Geography & Environmental Context

Micronesia in this age stretched across a thousand leagues of sea, encompassing East Micronesia—the Marshall Islands, Caroline Islands (including Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei, and Kosrae), and eastern Kiribati—and West Micronesia, including Palau, Yap, and the Mariana Islands.

Low coral atolls, volcanic high islands, and uplifted limestone ridges formed a constellation of lands bound by the Pacific’s great currents and the trade winds. Eastward lay the vast lagoons of the Marshalls and Carolines; westward, Palau’s barrier reefs and the Marianas’ volcanic chain marked the meeting of Asia and Oceania.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The onset of the Little Ice Age brought subtle cooling and erratic rainfall.

-

Atolls experienced severe droughts that desiccated freshwater lenses, punctuated by years of cyclones and floods.

-

Volcanic islands such as Pohnpei, Kosrae, and the Marianas moderated these extremes with rivers, springs, and fertile soils, sustaining denser populations.

-

ENSO (El Niño–Southern Oscillation) cycles oscillated between drought and deluge, forcing flexible agricultural and navigational adaptations.

Subsistence & Settlement

Across Micronesia, communities mastered life amid scarcity and abundance:

-

High islands supported irrigated taro and yam gardens, breadfruit groves, and banana terraces.

-

Atolls relied on coconut and pandanus orchards, pulaka pits, and lagoon fisheries, integrating arboriculture and aquaculture.

-

Settlements ringed lagoons or river valleys; stilt houses and canoe sheds lined coasts.

-

Domesticated pigs and chickens contributed to ritual feasting.

-

Populations were densest on Pohnpei, Kosrae, Yap, and the Marianas, where hierarchical chiefdoms arose, while atolls remained integrated through voyaging and tribute.

Technology & Material Culture

Micronesian innovation centered on mastery of the sea:

-

Canoe technology: Double-hulled and outrigger canoes ranged hundreds of kilometers, guided by etak star compasses, wave patterns, and bird flight.

-

Navigation: Stick charts in the Marshalls abstracted swells and island chains into learning tools for apprentices of the palu (navigators).

-

Architecture: Monumental stoneworks defined high islands—most famously Nan Madol on Pohnpei, a canal city of prismatic basalt that symbolized centralized authority.

-

Symbolic wealth: In Yap, rai stones—massive carved disks quarried in Palau and ferried home by canoe—embodied prestige and the fusion of navigation, economy, and spirituality.

-

Art & craft: Shell ornaments, woven mats, barkcloth, and carved ceremonial houses (bai) carried both utilitarian and sacred meaning.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Micronesia was a world woven by voyaging.

-

Eastward circuits: Navigators connected the Marshalls, eastern Carolines, and Kiribati through predictable seasonal routes, maintaining food redistribution and ritual alliance.

-

Central networks: Tribute flowed between atolls and volcanic centers like Pohnpei and Kosrae, where chiefs regulated exchange and labor.

-

Western corridors: Yap dominated an extensive sawei system—tributary relationships spanning hundreds of kilometers eastward. Palau served as the source of rai stone money and as a key bridge to island Southeast Asia.

-

Marianas chain: Unified by inter-island voyaging and shared architecture, from Guam to Saipan and Tinian, sustaining the Chamorro cultural sphere.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Micronesian worldviews fused navigation, ancestry, and hierarchy.

-

Sacred kingship: On Pohnpei and Kosrae, rulers claimed descent from divine ancestors, embodying authority through monumental centers like Nan Madol.

-

Ritual exchange: Feasting and gift-giving of food, mats, and ornaments reinforced social bonds and ecological redistribution.

-

Navigation as religion: Knowledge of stars, currents, and reefs was guarded and transmitted through chant and initiation.

-

Monumental symbolism: In the Marianas, latte stone pillars supported elite dwellings and anchored ancestral presence; in Palau, carved bai houses displayed mythic histories.

-

Oral traditions: Dances, songs, and genealogies encoded both navigation and cosmic law, linking each island to the broader order of sea and sky.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Resilience underpinned every aspect of Micronesian life:

-

Crop diversification: Breadfruit, coconut, and taro systems balanced against climatic variability.

-

Redistribution & alliance: Tribute networks transferred surplus food to drought-stricken atolls.

-

Conservation ethics: Lagoon and reef tenure governed fishing seasons and taboo zones.

-

Arboriculture: Deep-rooted tree crops stabilized soils and freshwater lenses.

-

Voyaging relief: Canoe expeditions moved provisions, labor, and kin between islands, ensuring survival through cooperation.

Transition (to 1539 CE)

By 1539 CE, Micronesia was a mature maritime civilization—its volcanic and coral worlds interlocked through navigation, exchange, and sacred kingship.

Nan Madol’s basalt canals, Yap’s stone currency, Palau’s carved bai, and Marianas’ latte pillars all spoke to a shared ethos of mastery over land and sea.

Europe had yet to intrude—Magellan’s fleet would sight the Marianas only in 1521—but Micronesians had already mapped their own cosmos in stars, stones, and stories.

Their oceanic networks, adaptive systems, and enduring cosmologies stood as one of humanity’s greatest achievements in the art of living within the sea itself.

Melanesia (1396–1539 CE)

Highland Gardens, Island Chiefdoms, and Expanding Voyaging Worlds

Geography & Environmental Context

Melanesia in this era comprised two great spheres: West Melanesia—New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, and Bougainville—and East Melanesia, including Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia, and the Solomon Islands (excluding Bougainville).

Rugged volcanic highlands, fertile valleys, and mangrove estuaries defined the larger islands; coral reefs, lagoons, and uplifted limestone ridges shaped the outer chains. From the misted mountains of New Guinea to the reefed coasts of Fiji and Vanuatu, landscapes yielded a rich mosaic of terrestrial and marine resources that sustained some of the Pacific’s densest pre-state populations.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The early Little Ice Age brought modest cooling and rainfall variability.

-

In New Guinea’s highlands, cooler nights shortened some growing seasons, but intensive terrace agriculture buffered production.

-

Coastal and island zones faced alternating droughts and floods linked to ENSO (El Niño–Southern Oscillation) cycles.

-

Periodic cyclones reshaped coastlines in the Solomons and Vanuatu, while volcanic eruptions in the Bismarcks renewed soils but occasionally displaced settlements.

Despite these fluctuations, fertile volcanic landscapes and flexible subsistence systems ensured long-term stability.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Highlands of New Guinea: Intensive irrigated taro terraces, kaukau (sweet potato) fields, and pig husbandry supported large, semi-permanent villages—among the world’s most densely settled non-literate societies.

-

Coastal and island Melanesia: Mixed horticulture of taro, yam, banana, breadfruit, and sago complemented reef and pelagic fishing. Domesticated pigs and chickens formed the basis of feasting economies.

-

Fortified settlements: Earthworks and palisades guarded villages in Vanuatu, Fiji, and the Solomons, reflecting inter-island rivalry and the consolidation of chiefly power.

-

Village patterns: Extended kin compounds clustered around ceremonial grounds and men’s houses, integrating social and ritual life.

Technology & Material Culture

Material traditions combined agricultural ingenuity with maritime reach.

-

Agriculture: Highland irrigation ditches, drainage systems, and stone terraces sustained continuous cropping. Coastal groups cultivated shifting gardens balanced by fallow rotation.

-

Seafaring: Outrigger and double-hulled canoes enabled inter-island trade, raiding, and alliance formation.

-

Crafts: Polished stone adzes, obsidian blades (especially from New Britain), and shell ornaments served as utilitarian and prestige items.

-

Architecture & art: Ceremonial houses adorned with carved masks, ancestor figures, and geometric motifs embodied social hierarchy and cosmological order. Woven mats, feather regalia, and barkcloth symbolized chiefly rank and exchange wealth.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Melanesia lay at the crossroads of the Pacific’s great exchange routes.

-

Westward connections: Coastal and island voyagers from the Bismarck and Admiralty Islands exchanged obsidian, shell, and ritual valuables across the Solomon Sea, linking to the Moluccas and Southeast Asia.

-

Eastward networks: Canoes from Fiji, Vanuatu, and the Solomons maintained regular contact, sharing goods, songs, and kin. Fijian chiefdoms traded ʻie tōga mats and ornaments with Tonga and Samoa, forging the first durable Melanesian–Polynesian interface.

-

Highland exchanges: Trails across New Guinea’s valleys carried salt, stone, and pigs between ecological zones, weaving dispersed settlements into dense webs of mutual obligation.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Ritual life unified politics, economy, and ecology.

-

Ancestral veneration: Lineages traced descent from founding spirits embodied in masks, skulls, and carved figures. Ceremonies renewed these bonds through dance, song, and feasting.

-

Feasting & exchange: Pigs and shell valuables circulated in cycles of reciprocity that displayed wealth and stabilized alliances.

-

Ceremonial architecture: Men’s houses in the Bismarcks and Sepik served as centers of initiation, governance, and sacred display.

-

Oral literature: Epics, chants, and creation songs transmitted genealogies and law, preserving identity across shifting alliances.

-

Kava ritual (Fiji): Ceremonial drinking linked chiefs and gods, anchoring authority in sacred etiquette and collective memory.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Melanesian communities integrated environmental management with social order.

-

Crop diversification: Multiple taro and yam varieties hedged against climatic stress.

-

Redistribution: Chiefs orchestrated the movement of surplus food to cyclone-affected islands.

-

Mobility & alliance: Canoe routes enabled refuge migration and inter-island support after disasters.

-

Ritual ecology: Sacred groves, reef taboos, and water deities codified conservation ethics long before European observation.

-

Highland engineering: Drainage and irrigation balanced fluctuating rainfall, ensuring sustained fertility even through cooler centuries.

Transition (to 1539 CE)

By 1539, Melanesia stood as a world of immense diversity—densely populated highlands, maritime chiefdoms, and far-reaching trade networks binding the Bismarcks, Solomons, Vanuatu, Fiji, and New Caledonia.

Fijian and Vanuatuan polities consolidated hierarchical rule; New Guinea’s highlands perfected intensive agriculture; Bougainville and the Bismarcks thrived on obsidian and shell trade.

Ritual exchange, ancestor veneration, and seafaring linked these systems into a single cultural continuum.

No European ships had yet crossed its seas, but Melanesia already sustained a flourishing civilization—complex, adaptive, and deeply interwoven with its ocean and mountains, poised on the threshold of global encounter.