Southern Australasia (1252 – 1395 CE): …

Years: 1252 - 1395

Southern Australasia (1252 – 1395 CE):

Intensified Horticulture, Māori Expansion, and Tasmanian Foraging

Geographic and Environmental Context

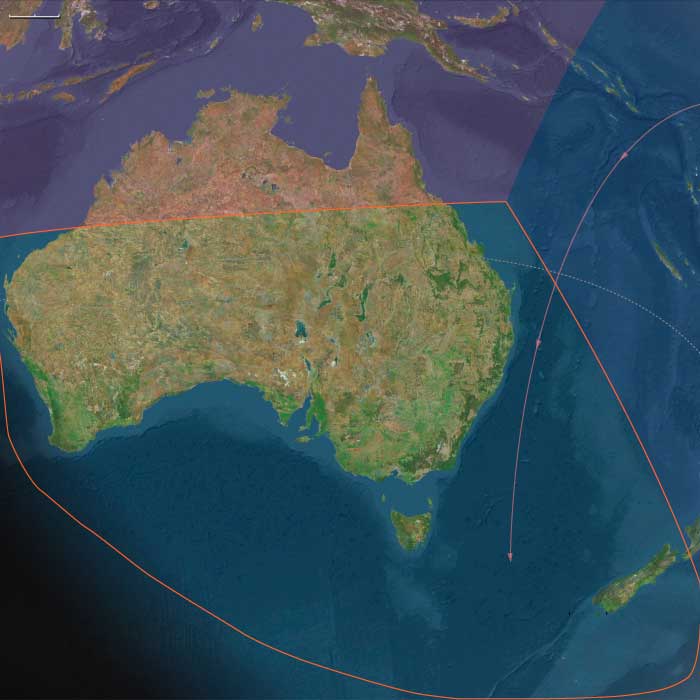

Southern Australasia includes southern Australia (New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Tasmania, and southern Western Australia) together with New Zealand’s South Island and the southwestern coast of the North Island.

-

Southern Australia: Coastal plains, eucalyptus woodlands, and riverine corridors (Murray–Darling) sustained hunter-gatherer economies.

-

Tasmania: Cold-temperate island environments supported littoral hunting and seasonal inland foraging.

-

New Zealand (South Island and southwest North Island): Newly settled by East Polynesians, featuring fertile valleys, temperate forests, and abundant fisheries.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

After c. 1300, the onset of the Little Ice Age brought cooler, wetter conditions.

-

In New Zealand, shorter growing seasons stressed tropical crops; kūmara and fern-root became staples.

-

In Tasmania and southern Australia, flexible foraging economies adapted easily to climatic variability.

Societies and Political Developments

-

New Zealand Māori:

Settlement expanded through the 13th–14th centuries; iwi and hapū consolidated territories anchored in canoe ancestry. Fortified pā multiplied as populations grew and competition for fertile valleys increased. -

South Island Māori (Ngāi Tahu):

Blended northern horticulture with southern hunting—moa, seals, and eels—creating mixed economies. -

Tasmania (Palawa peoples):

Small kin bands maintained seasonal foraging rounds; firestick farming created mosaics of grassland and woodland. -

Southern Australia:

Riverine and wetland settlements fostered dense aggregation and ceremonial life. Trade in greenstone and ochre linked regions without central states.

Economy and Trade

-

Māori horticulture: Kūmara in storage pits and ridged fields; taro, gourds, and cabbage-tree roots supplemented diets.

-

Protein sources: Moa, seals, fish, eels, and birds. South Island groups relied heavily on preserved game.

-

Tasmania: Shellfish, seals, kangaroos, wallabies, and roots.

-

Southern Australia: Riverine fish, waterfowl, marsupials, tubers, and yams; semi-permanent eel aquaculture at Lake Condah.

-

Trade: Pounamu (greenstone) moved across the South Island; ochre and axes circulated across the mainland.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Māori: Double-hulled canoes for fishing and trade; pā fortifications with palisades, ditches, and terraces; stone adzes and shell tools.

-

Tasmanians: Bone awls, wooden spears, fiber nets, bark canoes; no hafted stone axes or fishhooks, but highly adaptive seasonal mobility.

-

Mainland Australians: Ground-edge axes, fish weirs, eel traps, and firestick farming for habitat renewal.

-

Architecture: Māori whare, Australian bark shelters, and Tasmanian windbreak huts.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Canoe circuits linked Māori settlements across islands, integrating gardens, hunting zones, and pā networks.

Pounamu trails spanned the Southern Alps.

Murray–Darling rivers and Tasmanian channels facilitated trade, ceremony, and kin exchange.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Māori: Mana (authority) and tapu (sacred restriction) structured life; tohunga mediated between atua and people; canoe genealogies legitimized land rights.

-

Tasmanians and Australians: Dreaming or Law tied spirits to land and totem animals; rock art, songs, and ritual gatherings renewed cosmic order.

-

Ceremonial exchange affirmed social bonds across linguistic and ecological zones.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Māori diversification buffered climatic stress; pā ensured defense during competition.

-

Aboriginal firestick farming maintained productive ecotones.

-

Tasmanian mobility evened resource variability.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395 CE, Southern Australasia displayed dual trajectories:

-

Māori societies had forged resilient iwi/hapū polities, blending horticulture, hunting, fortified pā, and canoe exchange.

-

Aboriginal Australians and Tasmanians sustained enduring foraging economies anchored in ritual law and ecological expertise.

Together they exemplified temperate adaptation—from Māori proto-chiefdoms to forager confederacies—each resilient under the shifting climates of the Little Ice Age.

Groups

Topics

Commodoties

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 46611 total

We begin in the easternmost subregions and move westwardly around the globe, crossing the equator as many as six times to explore ever shorter time periods as we continue to circle the planet. The maps of the regions and subregions change to reflect the appropriate time period.

Narrow results by searching for a word or selecting from one or more of a dozen filters.

The Taíno (”good people”), an Arawakan group, populate Quisqueya, their name for the island presently known as Hispaniola. (An alternate name is Ayiti, meaning ”mountainous place”.)

Their Ciboney predecessors, an Arawakan people with lower technology, become concentrated in the west.

The Taíno practice a high-yielding form of slash-and-burn agriculture to grow their staple foods, cassava and yams.

Corn (maize), beans, squash, tobacco, peanuts (groundnuts), and peppers are also grown, and wild plants are gathered.

Birds, lizards, and small animals are hunted for food, the only domesticated animals being dogs and, occasionally, parrots used to decoy wild birds within range of hunters.

Fish and shellfish are another important food source.

Taíno settlements range from single families to groups of three thousand people, and houses are built of logs and poles with thatched roofs.

Men wear loincloths, and women wear aprons of cotton or palm fibers.

Both sexes paint themselves red on special occasions, and they wear earrings, nose rings, and necklaces, which are sometimes made of gold.

Other Taíno crafts are few; some pottery and baskets are made, and stone and wood are worked skillfully.

A favorite form of recreation among the Taíno is a ball game that they play on rectangular courts.

The Taíno follow an elaborate system of religious beliefs and rituals that involve the worship of spirits (zemis) by means of carved representations.

They also have a complex social order.

Their government is by hereditary chiefs and subchiefs, and there are classes of nobles, commoners, and serfs (or slaves).

Northeastern Eurasia (1252–1395 CE): Forest Frontiers, Steppe Realignments, and Northern Exchange

From the fur forests of the Volga–Oka basin to the salmon rivers of Sakhalin and Kamchatka, Northeastern Eurasia in the Lower Late Medieval Age formed the great ecological hinge between Europe and the Pacific. Across twelve time zones of tundra, taiga, and steppe, Mongol suzerainty, frontier trade, and native lifeways interwove into a vast and fluid world bound by furs, fish, and faith.

The Mongol World and the Forest Frontier

In the thirteenth century, the Mongol conquests reshaped the political geography of the northern continent. The Golden Horde, ruling from its Volga capital at Sarai, dominated the steppes between the Urals and the Dnieper. Tribute, census, and courier systems extended northward into the Rus’ forests, transforming older principalities into tributary states. Farther east, the Ilkhanid, Chagatai, and Yuan branches of the empire controlled Central Asia, Iran, and China, enclosing the great Eurasian fur belt within a single imperial framework.

Beneath this canopy of conquest, indigenous societies persisted. The Khanty, Mansi, and Selkup peoples of the Ob–Irtysh–Yenisei valleys, and the Evenki hunters of the taiga, maintained clan economies of fishing, trapping, and seasonal herding. Furs—sable, marten, squirrel, and ermine—moved down frozen rivers to the tribute markets of the Golden Horde, exchanged for salt, iron, and cloth. In the Altai and Sayan mountains, Turkic–Mongol pastoralists grazed herds of horses, sheep, and camels, while the Yenisei Kyrgyz and rising Oirat confederations negotiated power between forest and steppe.

East Europe under Mongol Suzerainty

To the west, the principalities of Rus’ adapted to life under Horde rule. The Mongol campaigns of 1237–1240 shattered the Kievan commonwealth, yet cities such as Vladimir, Suzdal’, and Tver’ survived by paying tribute. The new power center of Moscow, under Ivan I Kalita and Dmitry Donskoy, rose as the Horde’s favored tax collector. The victory at Kulikovo Field (1380) became a lasting symbol of resistance, though the city was soon sacked by Toqtamish (1382).

Meanwhile, the Novgorod Republic, shielded by forests and swamps, retained autonomy under Horde suzerainty. Governed by its veche assembly, it thrived on the fur trade, sending pelts, wax, and honey through Hanseatic kontorsat Visby and Toruń. To the southwest, Lithuania expanded under Gediminas and Algirdas, seizing Kiev (1362) and extending rule over most of Belarus and Ukraine. The Union of Krewo (1385) linked Lithuania and Poland in a dynastic and religious alliance, bringing the western forest-steppe into Latin Christendom.

The Siberian and Amur Realms

Beyond the Urals, Mongol authority thinned but trade intensified. The Ob, Irtysh, and Yenisei corridors became the highways of the fur economy, their frozen surfaces serving as winter roads. The Golden Horde levied tribute through steppe brokers, while taiga hunters retained mobility and autonomy. By the fourteenth century, the Oirats of the Altai had begun to eclipse older tribes, and Islam spread among the southern steppe Tatars even as shamanic traditions persisted in the forests.

Farther east, along the Amur, the Yuan dynasty extended its reach to the Pacific. Expeditions of the 1270s–1330s subdued Nivkh and Nanai clans on Sakhalin, exacting furs and falcons for the imperial tribute rolls. The empire’s northernmost subjects sent offerings of sable and eagle feathers to Beijing in exchange for silk, iron, and prestige goods. In northern Hokkaidō, Ainu communities consolidated during this same period, trading dried fish and furs to Wajin (Japanese) merchants from Honshū. Ritual leaders and traders emerged as chiefs of semi-hereditary domains, their culture crystallized in the bear-sending rite (iyomante) that honored the spirits of animal patrons.

In the Kamchatka Peninsula, the Koryak herders and Itelmen fishers combined coastal sea-mammal hunting with inland reindeer mobility, while the Chukchi linked the Bering shore to the Siberian interior. Across the Bering Strait, contacts with Yupik and Inuit communities remained episodic but steady, transferring tools, hides, and myths between Eurasia and America.

Economies of Fur, Fish, and Exchange

Everywhere across the northern latitudes, the fur trade functioned as currency. Furs moved west to the Volga, south to the Yuan and Ming courts, and east into Japanese and Korean markets. Iron and cloth, scarce in the north, circulated back through Baltic merchants, Mongol caravans, and Wajin traders. In the forest-steppe and taiga, winter ice served as the season of transport: sled convoys and dog teams carried tribute along frozen rivers, while summer canoes threaded through lakes and portages.

In the Baltic and Arctic margins, fishing and seal hunting matched the fur trade in importance. Dried salmon, cod, and seal oil provisioned both villages and ships. Novgorodian merchants tapped the fisheries of the White Sea, while Ainu and Amur fishermen adapted weirs, wicker traps, and bone harpoons to each river system. In the taiga, beekeeping and reindeer herding supplemented hunting, creating mixed economies that could absorb climatic shocks.

Belief, Ritual, and Cultural Synthesis

Despite Mongol conquest and tributary hierarchies, Northeastern Eurasia retained a remarkable religious pluralism.

-

In the Rus’ lands, Orthodox Christianity spread northward through monasteries founded by Sergius of Radonezh, while the Horde’s ruling elite adopted Islam yet tolerated Christian and Jewish communities.

-

In the Amur and Hokkaidō zones, animist cosmologies thrived: Ainu and Nivkh shamans honored salmon, bears, and sea spirits through elaborate rites of reciprocity.

-

Across the steppe and forest, Tengrist and Buddhist influences mingled with Islamic and Christian forms, producing a syncretic frontier spirituality.

Ritual, in every climate, served social cohesion. Feasts, first-fish rites, and shared tribute ceremonies governed resource use and mediated clan disputes, ensuring survival where centralized states could not.

Adaptation and Resilience

Ecological diversity underpinned endurance. Communities combined herding, hunting, fishing, and limited cultivation according to latitude and season. When steppe pastures failed, forest products and furs replaced lost income; when fishing runs declined, herders moved south or west. Tribute relations with distant empires—whether to Sarai, Dadu, or Moscow—were accepted as the price of stability and access to imported goods. Across regions, mobility, not stasis, defined resilience: from the sled trails of the Yenisei to the plank boats of the Amur, the peoples of the north adjusted to climate and empire alike.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395 CE, Northeastern Eurasia had coalesced into a vast but loosely integrated frontier.

-

The Golden Horde still dominated the western steppe, though fractured by internal wars and Timur’s invasions.

-

In the forests of Rus’, Moscow and Novgorod emerged as twin poles of power and commerce.

-

The Oirats consolidated in the Altai, while the Ming inherited Yuan tributary patterns along the Amur.

-

Ainu and Amur peoples sustained independent economies of salmon, fur, and ritual, their autonomy protected by distance and climate.

Across the entire north, the twin currencies of fur and fish and the languages of trade and tribute bound Europe and Asia together. The region’s enduring ecological wealth and mobility made it the silent backbone of late medieval Eurasia—supplying luxury markets, sustaining frontiers, and foreshadowing the great northern expansions of the centuries to come.

Northeast Asia (1252 – 1395 CE): Ainu Consolidation, Yuan Campaigns on Sakhalin, and Amur–Kamchatka Exchange

Geographic and Environmental Context

Northeast Asia includes Siberia east of the Lena River basin to the Pacific, the Russian Far East (excluding southern Primorsky Krai/Vladivostok), northern Hokkaidō (above the southwestern peninsula), and China’s extreme northeastern Heilongjiang.

-

A cold belt of taiga, tundra, and maritime coasts: the Amur–Ussuri lowlands and Sakhalin straits; the Okhotsk shores and Kamchatka; the northern half of Hokkaidō; and the lower Amur–Heilongjiang basin.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

Under the late Medieval Warm Period, summers were modestly longer along river valleys and Hokkaidō’s lowlands, improving salmon runs and plant yields; interiors remained subarctic.

-

Sea ice in the Okhotsk seasonally retreated from river mouths, sustaining rich polynyas for seals and salmon.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Lower Amur–Sakhalin (Nivkh, Ulch, Nanai/Hezhe): clan villages continued salmon and seal economies; from the 1270s the Yuan court mounted repeated expeditions to Sakhalin, compelling tribute from Nivkh and intervening in conflicts with Ainu groups. By the early 14th century a Yuan-mediated tribute rhythm (furs, falcons) bound the lower Amur and Sakhalin to continental centers.

-

Northern Hokkaidō (Ainu): Satsumon-era communities coalesced into distinct Ainu culture. Exchange with Wajin merchants from northern Honshū intensified (iron blades, lacquerware, textiles) in return for furs, dried fish, and eagle feathers. Ainu lineages consolidated coastal–river territories; ritual and trade leaders gained prominence.

-

Kamchatka and Chukotka (Koryak, Itelmen, Chukchi): Koryak reindeer herders and coastal sea-mammal hunters, and Itelmen salmon fishers, maintained mobile lifeways; Chukchi linked the Bering shore to interior herding and hunting. Cross-Strait contacts with Siberian Yupik and Inuit remained episodic but durable.

-

Heilongjiang fringe: after the fall of Jin (1234), Mongol/Yuan authority extended into the Amur basin; by the 1370s–1390s the Ming replacement of Yuan reduced direct pressure, but riverine clans retained tributary habits with southern courts.

Economy and Trade

-

Fur frontiers: sable, marten, fox, and otter pelts moved by canoe and winter trails to Yuan depots and later Ming-border marts; eagle hawks (falcons) were prized court tributes.

-

Fish and sea-mammal products: dried salmon, seal oil, and whale by-products were staples for subsistence and exchange from Hokkaidō to Kamchatka.

-

Iron inflows: most metal arrived via trade—Yuan intermediaries on the Amur, Wajin merchants to Hokkaidō, or recycled pieces from coastal wreckage—resharpened locally into knives, spearheads, and adze bits.

-

Local manufactures: carved wooden utensils, birch-bark containers, bone and antler points, and woven fish nets remained ubiquitous.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Riverine fisheries: weirs and wicker traps on the Amur, Teshio, and Ishikari; drying racks supported winter stores.

-

Maritime hunting: toggling harpoons, lashed bone blades, and skin or plank canoes in Okhotsk and Kamchatka; coastal drive techniques for seals.

-

Taiga mobility: skis, snowshoes, dog or reindeer sleds in interior corridors; bark canoes and plank craft in ice-free seasons.

-

Village forms: semi-subterranean or plank houses in Amur and Hokkaidō riverlands; conical hide or bark shelters in mobile herding/hunting zones.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Amur–Sakhalin–Okhotsk loop: tied Nivkh, Nanai, and Ulch villages to Yuan tribute routes and inter-clan exchange; winter ice enabled crossings to Sakhalin.

-

La Pérouse Strait & northern Hokkaidō coasts: Ainu–Wajin trade intensified along Hokkaidō’s north and east shores; coastal nodes doubled as ritual centers.

-

Kamchatka–Bering shore: Koryak, Itelmen, and Chukchi circuits connected reindeer pastures, salmon rivers, and sea-mammal rookeries, with occasional cross-Strait trade.

-

Forest portages: linked lower Amur villages to upland Evenki hunters and to Heilongjiang markets.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Ainu: the bear-sending rite (iyomante) and offerings to river and mountain kamuy framed reciprocity with animal masters; plank-house altars and carved inau marked sacred exchanges.

-

Amur peoples (Nivkh/Nanai): salmon and sea spirits honored through first-fish rites; clan shamans mediated illness, hunting luck, and weather.

-

Koryak/Itelmen/Chukchi: sea and sky deities, ancestral patrons of herds and rookeries; drums and trance practices guided hunting seasons and migrations.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Portfolio subsistence: salmon + sea mammals + gathered plants (and in some Ainu districts, limited millet/barley gardening) buffered bad runs or ice failures.

-

Mobility: seasonal moves among coast, river, and interior taiga maintained access to fish, game, and reliable water.

-

Tribute pragmatism: accommodation to Yuan demands (furs, falcons) traded coercion risk for iron, cloth, and prestige items; after 1368, shifting to Ming border exchange reduced military pressure while preserving trade.

-

Ritual cohesion: communal feasts, first-catch rites, and iyomante reinforced sharing rules and managed inter-clan tensions.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395, Northeast Asia was a fur-and-fish frontier knit to imperial markets yet culturally anchored in northern lifeways:

-

Yuan campaigns on Sakhalin had drawn Nivkh and Ainu into a tributary orbit without dismantling local autonomy.

-

Ainu society in Hokkaidō consolidated, deepening trade with Wajin while preserving distinctive ritual authority.

-

Koryak, Itelmen, and Chukchi maintained resilient mobile economies across Kamchatka and the Bering shore.

-

As Ming replaced Yuan, imperial reach loosened along the Amur, but the fur corridor endured—setting the stage for later 15th–17th-century contests among Ainu, Wajin, Ming, and, eventually, Russian newcomers.

Northern North America (1252 – 1395 CE): Salmon Chiefdoms, Iroquoian Ascendancy, and the Continental Exchange

Across the northern half of the continent, from Alaska’s fjords to Florida’s mangroves, the centuries between 1252 and 1395 were marked by both consolidation and transformation. As the warmth of the Medieval era ebbed, cooler and stormier centuries tested the great riverine and coastal societies of North America—but they endured through ingenuity, mobility, and exchange. The result was a web of civilizations linked by trade in salmon, copper, shells, maize, and ideology, stretching from the Arctic whaling camps to the Mississippi mounds and the Californian shores.

Northwestern Shores and Salmon Kingdoms

Along the North Pacific Coast, maritime chiefdoms reached their peak. From the fjords of Southeast Alaska to the Salish Sea, ranked lineages of Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Kwakwaka’wakw, and Coast Salish peoples controlled salmon rivers, tidal flats, and cedar forests. House-crests, totems, and potlatch feasts codified rights to resources, transforming stored salmon, seal oil, and copper ornaments into instruments of status and diplomacy. In the Gulf of Alaska and Aleutian Islands, the Unangan and Sugpiaq built skin-covered boats and toggling harpoons to hunt seals and whales, while Arctic Iñupiat communities of Thule descent perfected cooperative bowhead hunts along the frozen shore.

Inland, Dene (Athabaskan) peoples—Gwich’in, Kaska, Tahltan, and others—moved between river fisheries and caribou ranges. They exchanged native copper, obsidian, and hides for coastal eulachon oil carried over mountain “grease trails.” Together, these coastal and interior systems formed a salmon-and-grease economy that tied the Yukon to Puget Sound and proved resilient under the first chills of the Little Ice Age.

Eastern Forests and Great Lakes Peoples

Far across the continent, the riverine chiefdoms of the Mississippi Valley waned as new polities rose. The great city of Cahokia, weakened by floods, droughts, and internal stress, was abandoned by the mid-fourteenth century. Yet its mound-building legacy endured in the Lower Mississippi, where Natchez, Plaquemine, and Etowah peoples sustained maize agriculture and ritual kingship. Farther north, around the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence, Iroquoian and Algonquian villages flourished.

The Iroquoian towns of Ontario and New York, enclosed by palisades and defined by longhouse clans, organized around matrilineal lineages that prefigured later confederacies. Their maize-beans-squash agriculture supported dense settlements; hunting and fishing supplied surpluses for diplomacy and war. To their north and east, Algonquian nations combined farming, fishing, and forest foraging in a flexible cycle that ensured survival through climatic fluctuation.

Meanwhile, on the continent’s frozen edge, the Inuit (Thule) expanded across the Arctic archipelago and into Greenland, displacing the Norse settlers whose farms succumbed to failing pastures and isolation. The last Norse church bells faded in the late fourteenth century as Inuit umiaks and sled teams dominated the northern seas.

Western Deserts, Plateaus, and Pacific Rim

Southward and inland, in the mountains and deserts of the West, the onset of aridity reshaped communities. In the Southwest, the Ancestral Puebloans entered the Pueblo IV era, gathering into larger towns on the Zuni and Hopimesas and along the Rio Grande. Painted kivas and katsina ceremonies unified villages under shared ritual calendars. In the Hohokam lowlands of the Salt and Gila rivers, extensive irrigation networks continued, though salinization and drought forced migration and reorganization.

Across the Great Basin, small foraging bands expanded pine-nut and seed use; in the California valleys and coasts, Chumash, Miwok, and Ohlone peoples created rich economies based on acorns, shell-bead currency, and ocean trade. Chumash plank canoes (tomols) connected the Channel Islands to mainland markets, exchanging shell beads, fish, and pigments. These Pacific chiefdoms paralleled their northern neighbors in complexity, forging an unbroken coastal network of ritual exchange and seaborne commerce.

Southern Plains and Gulf Chiefdoms

Eastward, the Lower Mississippi and Gulf Coast retained a tapestry of mound-town chiefdoms and coastal polities. At Spiro (Oklahoma) and Etowah (Georgia), elaborate copper plates, shell gorgets, and birdman effigies reflected the ceremonial universe of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex. Along the Gulf, the Calusa and other coastal fisher-chiefs ruled estuaries from fortified towns, wielding sacred bundles and tribute networks sustained by marine abundance.

In the Texas–Oklahoma plains, bison hunting intensified, while maize farming along rivers provided stability. Across the Southwest–Plains transition, trade carried turquoise, bison robes, shells, and macaws in circuits reaching from Mesoamerica to the Mississippi.

Economy, Exchange, and Technology

Northern North America thrived on environmental variety.

-

Coasts and rivers: salmon, cod, and eulachon oil in the Pacific; herring and shellfish in the Atlantic.

-

Forests: maize, beans, acorns, and wild rice anchored diverse agricultures.

-

Mountains and plains: obsidian, copper, and bison products supplied continental trade.

Canoes—dugout, plank, or birchbark—were universal instruments of movement; so were snowshoes, sleds, and storage pits. Long-distance corridors connected every major culture zone: Inside Passage fleets linked Alaska to Puget Sound; the Mississippi and Missouri funneled goods north and south; Great Lakes waterways met Hudson Bay routes; and overland paths tied Puebloan mesas to Gulf chiefdoms and the Pacific coast.

Belief and Symbolism

Ritual life revolved around animals, ancestors, and celestial order.

-

North Pacific lineages carved crests and totems affirming ties to salmon and bear spirits; first-salmon ceremonies renewed ecological balance.

-

Mississippian societies celebrated fertility and war through birdman imagery, mound rituals, and sacred fire.

-

Pueblo kivas sustained cyclical dance traditions linking earth and sky; Chumash voyagers mapped constellations into their maritime cosmology.

-

Iroquoian longhouse rituals honored Sky Woman and the Three Sisters of agriculture; Algonquian vision quests sought harmony with guardian spirits.

-

In the Arctic, whale and seal ceremonies reaffirmed reciprocity between human and animal worlds.

Everywhere, spiritual practice reinforced environmental stewardship and social solidarity.

Adaptation and Resilience

The onset of cooler climates demanded flexibility. Coastal storage economies—smoked fish, rendered grease, dried acorns—bridged lean seasons. River and lake villages relocated when floods or silt clogged channels. Irrigation, mound renewal, and ritual redistribution managed ecological stress. Mobility and diplomacy mitigated conflict: alliances forged through feasts, intermarriage, and ceremonial trade allowed populations to recover from famine or warfare.

Despite regional collapse—Cahokia in the Mississippi valley, Norse Greenland in the Arctic—neighboring societies restructured rather than declined. Diversity of subsistence, surplus storage, and shared ideology ensured continuity through climate shock and disease.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395 CE, Northern North America was a continent of mature, interconnected societies.

The North Pacific chiefdoms refined hierarchical systems based on salmon and cedar wealth; the Thule-derived Inuit achieved their greatest whaling expansion before later cooling; and Dene traders spanned interior forests with copper and fur exchange.

In the east, Iroquoian and Algonquian peoples dominated the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence, heirs to the Mississippian legacy; Inuit hunters replaced the Norse in Greenland’s fjords.

In the south and west, Pueblo IV, Chumash, and Gulf Coast societies preserved complex ritual economies tied to broader continental networks.

Together these worlds formed a continuous northern commonwealth—one bound by waterways, storied landscapes, and ecological intelligence. Through adaptability, mobility, and trade, the peoples of Northern North America sustained cultural florescence on the eve of the colder centuries to come.

Northwestern North America (1252 – 1395 CE): Salmon Chiefdoms, Thule Whalers, and the Grease Trails

Geographic and Environmental Context

Northwestern North America includes Alaska, western Canada (Yukon and British Columbia), Washington, northern Idaho, northwestern Montana, Oregon, and the northwestern portions of California.

-

Coastal fjords and archipelagos (Southeast Alaska, Haida Gwaii, Vancouver Island, the Salish Sea) supported dense plank-house towns.

-

Gulf of Alaska and Aleutian coasts sustained sea-mammal hunters and offshore fishers.

-

Interior plateaus and river valleys (Stikine, Skeena, Fraser, Columbia, Yukon) tied foragers and farmers into salmon and trade networks.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

The late Medieval Warm Period gave way to the early Little Ice Age after c. 1300: slightly cooler, stormier coasts and more variable snowpacks inland.

-

Salmon runs remained robust but fluctuated by river; cooler seas favored some stocks while harsher winters increased risk for interior travel.

-

Along the Arctic rim, sea-ice season lengthened modestly late in the period, without halting whale migrations.

Societies and Political Developments

-

North Pacific Coast chiefdoms (Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Kwakwakaʼwakw, Coast Salish):

-

Ranked house-lineages controlled salmon weirs, tidal flats, cedar groves, and canoe landings.

-

Competitive feasting and alliance-building (potlatch-like institutions) intensified; warfare over fisheries and trade routes is attested in oral histories.

-

-

Gulf of Alaska & Aleutians (Unangan/ Aleut, Sugpiaq/Alutiiq):

-

Maritime villages specialized in sea-lion, seal, and offshore fish, with flexible alliances between winter villages and summer camps.

-

-

Arctic Alaska (Iñupiat/Thule):

-

Thule-derived whaling societies flourished on bowhead migrations; large multi-house communities and cooperative whale hunts peaked before later 15th-century cooling.

-

-

Interior Dene (Athabaskan) (Gwich’in, Kaska, Carrier, Tahltan, among others):

-

Highly mobile river-and-taiga bands coordinated seasonal caribou hunts and salmon fishing; trade partnerships linked interior copper and obsidian to coastal towns.

-

Economy and Trade

-

Salmon surplus economies supported smoking houses, oil rendering, and long-term storage; eulachon grease from the Skeena–Nass became a premier trade good moved on grease trails to interior partners.

-

Prestige metals and shells: native copper (Upper Yukon/Alaska, northwestern BC), dentalium shells, and carved antler circulated as wealth.

-

Maritime staples: sea-mammal oil, hides, baleen (Arctic and Gulf coasts); dried halibut and cod (outer coasts).

-

Interior staples: caribou, moose, berries, and roots complemented river fish; canoe-borne exchange reached well into the Columbia and Fraser networks.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Cedar technologies (coast): monumental plank houses; box-and-steam cooking; bentwood chests; dugout canoes for freight and war.

-

Fishing systems: tidal weirs, stake traps, reef-nets (Salish Sea), river weirs and dip-nets on interior rapids.

-

Arctic/Gulf craft: skin boats and kayaks (qayaq), open whale-boats (umiak), toggling harpoons, compound lines and drags for large sea mammals.

-

Hunting kit (interior): sinew-backed bows, copper and stone points, snowshoes, toboggans; smokehouses and cache pits for winter stores.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Inside Passage stitched together Tlingit–Haida–Kwakwakaʼwakw–Salish towns in year-round canoe traffic.

-

Grease trails climbed from eulachon rivers (Nass, Skeena, Bella Coola) across mountain passes to interior Dene partners.

-

Yukon–Copper–Tanana waterways linked interior copper sources to coastal brokers.

-

Arctic littoral hosted seasonal whaling migrations and trade fairs among Iñupiat communities.

Belief and Symbolism

-

House-crest systems (coast) articulated lineage rights to places and stories; crest poles, regalia, and feasting transformed surplus into status and alliance.

-

Shamanic healing and spirit guardians governed luck in hunting and warfare; rituals marked first-salmon, first-whale, and eulachon runs.

-

Iñupiat/Thule whale ceremonies honored animal masters and redistributed meat and oil across households.

-

Dene narratives mapped rivers and passes as sacred geographies anchoring seasonal movement.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Portfolio economies (salmon + sea mammals + terrestrial game + stored oil) buffered climate swings at the onset of the Little Ice Age.

-

Storage and redistribution—smoked fish, rendered grease, whale shares—stabilized communities through bad runs and hard winters.

-

Flexible mobility: interior bands shifted traplines and wintering grounds; coastal towns maintained alternate fishing sites and alliance harbors.

-

Conflict management: diplomacy and ceremonial gifting balanced raiding over high-value fisheries and trade chokepoints.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395, Northwestern North America stood out as a maritime-and-riverine commonwealth:

-

Pacific chiefdoms refined lineage rule and long-distance trade around salmon and grease.

-

Thule-derived Iñupiat communities reached a high point of cooperative whaling before later climatic tightening.

-

Interior Dene maintained wide exchange networks linking copper, furs, and food stores to the coast.

These resilient systems—house societies, storage economies, canoe corridors, and Arctic whaling alliances—carried the region successfully into the colder centuries that followed.

Polynesia (1252–1395 CE)

Voyaging Commonwealths and Island Ecologies

Geographic & Environmental Framework

Polynesia in the Lower Late Medieval Age stretched across the central and eastern Pacific—from the volcanic high islands and atolls of Hawaiʻi, Samoa, Tonga, and the Societies to the far eastern outliers of Rapa Nui and Pitcairn–Henderson.

High volcanic islands such as Hawaiʻi, Tonga, and Tahiti sustained fertile valleys, leeward drylands, and reef-lined coasts; low atolls like Tuvalu and Tokelau depended on coconut and breadfruit arboriculture.

This vast oceanic domain formed a connected world of voyaging, ritual, and ecological engineering, bound by canoe routes, genealogies, and shared ritual centers such as Taputapuātea on Ra‘iātea.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The waning Medieval Warm Period and onset of the Little Ice Age (from c. 1300 CE) brought cooler seas and rainfall variability:

-

High islands: alternated between drought and flood years, but diversified agriculture and irrigation stabilized production.

-

Atolls: faced heightened risk from storm surges and prolonged dry spells.

-

Eastern margins (Rapa Nui–Pitcairn): isolation deepened as cooler currents and winds curtailed long-range voyaging.

Despite these shifts, Polynesian societies demonstrated remarkable resilience through integrated ridge-to-reef economies and adaptive governance.

Societies & Political Developments

North Polynesia – Hawaiian Chiefdoms:

-

On Oʻahu, Maui, and Kauaʻi, chiefly hierarchies (aliʻi nui) consolidated authority through control of irrigated valleys and coastal fishponds (loko iʻa).

-

Land divisions (ahupuaʻa) extended from mountain ridges to reefs, coordinating upland agriculture with nearshore aquaculture.

-

Monumental heiau temples, elaborate feather regalia, and the tightening of kapu laws affirmed chiefly sanctity and ecological control.

West Polynesia – Tongan, Samoan, and Society Polities:

-

The Tuʻi Tonga dynasty presided over a far-reaching maritime hegemony linking Samoa, the Cooks, and parts of the Societies through tribute and alliance.

-

Samoan federations balanced power among matai (titled chiefs) and orators, cultivating political stability through councils and ritual exchange.

-

The Society Islands centered on Ra‘iātea’s Taputapuātea marae, a sacred convocation site where chiefs renewed voyaging covenants and ritual genealogies.

-

In the Marquesas, valley chiefdoms grew populous, elaborating plaza architecture, tattooing, and carving traditions.

East Polynesia – Rapa Nui and Pitcairn–Henderson:

-

On Rapa Nui, lineage rivalries culminated in the great era of moai carving (13th–15th centuries); ancestral statues on coastal ahu embodied political legitimacy.

-

Deforestation and soil depletion signaled mounting ecological strain.

-

Pitcairn–Henderson societies declined as isolation severed exchange with Mangareva and the Societies, leading to eventual abandonment.

Economy & Exchange Networks

Across the region, intensive agro-aquatic production sustained large populations:

-

Irrigated taro terraces (loʻi kalo) in windward valleys, dryland field grids of sweet potato and yam on leeward slopes, and breadfruit–coconut arboriculture on atolls formed the subsistence base.

-

Fishponds and reef management ensured steady protein yields.

-

Trade circuits carried fine mats (ʻie tōga), red feathers, basalt adze blanks, pearl shell, and sennit cordage between Tonga, Samoa, the Cooks, and the Societies.

-

Long-distance voyaging diminished after 1300 CE, but ritual contact and shared myth maintained unity across the Polynesian triangle.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Hydraulic works: stone-lined irrigation ditches, check dams, and terrace mosaics maximized valley fertility.

-

Fishpond engineering: seawalls with mākāhā gates regulated recruitment and harvest cycles.

-

Canoe technology: double-hulled voyaging craft (waʻa kaulua) navigated by stars, swells, and seabird patterns.

-

Craft industries: basalt adze manufacture, barkcloth (kapa) production, and featherwork for chiefly regalia expressed technical and aesthetic sophistication.

-

Rapa Nui: megalithic quarrying and carving at Rano Raraku demonstrated unparalleled engineering using basalt and tuff.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Tonga–Samoa–Cooks–Societies arc: core political and ritual corridor of the Polynesian world, anchored by Taputapuātea.

-

Hawaiian channels: regular canoe routes bound Oʻahu, Maui, and Kauaʻi; voyages to Hawaiʻi Island maintained cultural unity.

-

Atoll shuttles: Tuvalu and Tokelau relied on canoe convoys to exchange salt fish and fiber goods for starch staples from high islands.

-

Eastern extremities: Rapa Nui and Pitcairn lay increasingly beyond active navigation but retained mythic presence in oral traditions.

Belief & Symbolism

Polynesian cosmologies joined ecology, lineage, and divine order:

-

Divine kingship in Tonga and Hawaiʻi linked chiefs to gods of sky and sea.

-

Taputapuātea ceremonies renewed voyaging oaths and sacred genealogies across archipelagos.

-

Kapu systems regulated fishing, planting, and social hierarchy, embedding environmental stewardship within religious law.

-

On Rapa Nui, moai and later the bird-man cult at Orongo expressed evolving balances between ancestor veneration and fertility ritual.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Resilience strategies were ecological and institutional:

-

Diversified food webs—wet taro, dryland roots, arboriculture, fishponds, reef fisheries—buffered climatic shocks.

-

Ritual closures safeguarded spawning grounds; corvée labor rebuilt terraces and ponds after storms.

-

Inter-island reciprocity and marriage alliances redistributed surplus after droughts or cyclones.

-

On Rapa Nui, stone mulching and rock gardens extended cultivation as deforestation advanced.

Technology & Power Shifts (Conflict Dynamics)

-

Expansion of chiefly estates and temple building intensified labor mobilization; intermittent warfare over land and prestige recurred across Oʻahu–Maui and among Tongan satellites.

-

Control of fishponds, irrigated valleys, and tribute networks defined chiefly authority.

-

Voyaging guilds and priestly lineages mediated disputes, maintaining overarching ritual unity despite political rivalry.

Transition (to 1395 CE)

By 1395 CE, Polynesia had matured into an archipelagic commonwealth of engineered landscapes and interlinked chiefdoms:

-

North Polynesia’s fishpond states and ahupuaʻa governance integrated mountain, valley, and reef.

-

West Polynesia’s Tuʻi Tonga hegemony and Taputapuātea rituals maintained trans-oceanic cohesion.

-

East Polynesia’s Rapa Nui monumentality marked both creative zenith and ecological vulnerability.

Together, these societies exemplified a Pacific synthesis of maritime mastery, ecological design, and sacred polity, resilient under the shifting climates of the early Little Ice Age and poised to evolve into the complex systems that Europeans would one day encounter.

North Polynesia (1252 – 1395 CE): Chiefly Consolidation, Fishpond States, and Ridge-to-Reef Governance

Geographic and Environmental Context

North Polynesia includes the Hawaiian Islands chain (except the Big Island of Hawaiʻi) and Midway Atoll—principally Oʻahu, Maui, Kauaʻi, Molokaʻi, Lānaʻi, Niʻihau, and Midway.

-

High islands offered windward wet valleys and leeward coastal plains suited to intensive irrigation and pond aquaculture; fringing reefs and embayments supplied stable nearshore fisheries.

-

Midway remained marginal—visited episodically but not permanently settled.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

The late Medieval Warm Period gave way to the early Little Ice Age (c. 1300s), bringing modestly cooler, more variable rainfall.

-

Intensified infrastructure—terraces, ditchworks, and fishponds— buffered dry spells on leeward coasts; windward valleys continued to deliver high taro yields.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Chiefly stratification deepened under aliʻi and aliʻi nui on Oʻahu, Maui, and Kauaʻi.

-

Land-and-water administration matured into robust ahupuaʻa (ridge-to-reef) jurisdictions, coordinated by district stewards under high chiefs.

-

Inter-island rivalries sharpened—alliances and warfare reshaped boundaries among Oʻahu–Maui–Molokaʻi–Kauaʻi polities; Niʻihau remained closely tied to Kauaʻi.

-

Elite courts patronized specialists—irrigation overseers, fishpond managers, navigators, chanters—entrenching chiefly power.

Economy and Trade

-

Intensive agro-aquatic production: windward loʻi kalo (irrigated taro) coupled with large coastal fishponds (loko iʻa) yielded reliable surpluses of kalo and finfish (e.g., ʻamaʻama, awa).

-

Dryland belts produced ʻuala (sweet potato), gourds, and sugarcane; salt works and fish-drying on leeward flats fed inter-district exchange.

-

Inter-island circulation moved canoe timber, fine barkcloth, basalt adze blanks, feather regalia, and preserved foods among the main high islands; Midway played no regular role.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Hydraulic engineering: stone-lined canals, check dams, and terrace mosaics maximized valley throughflow to loʻi kalo.

-

Fishpond systems: seawalls with sluice gates (mākāhā) managed recruitment and harvest; staggered pond complexes spread risk.

-

Vessels & tools: double-hulled canoes (waʻa kaulua) for inter-island voyaging; basalt adzes and coral-abraders for carpentry; fiber nets and basket traps for reef/pond fisheries.

-

Storage & processing: stone platforms and house-lofts for dried fish and poi batter stabilized year-round provisioning.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Regular canoe circuits linked Oʻahu–Maui–Molokaʻi–Lānaʻi and Kauaʻi–Niʻihau clusters; channels doubled as diplomatic frontiers and trade lanes.

-

Intra-island networks tied upland irrigation headworks to coastal pond precincts within ahupuaʻa boundaries, facilitating rapid mobilization of labor.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Temple complexes (heiau) proliferated—agricultural, fishing, healing, and war temples presided over seasonal rites that synchronized labor and legitimated chiefly rule.

-

The kapu system regulated access to water heads, pond gates, spawning grounds, and sacred groves, embedding ecology in law.

-

Elite feather regalia and genealogical chants affirmed aliʻi sanctity and seniority.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Portfolio production—wet taro + dryland crops + fishponds + reef fisheries—created redundancy against droughts and storms.

-

Coordinated corvée maintained ditches, terraces, and pond walls after flood damage; ritual closures allowed stock recovery.

-

Inter-island diplomacy (marriage ties, tribute exchanges) mitigated conflict and smoothed resource imbalances.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395, North Polynesia had evolved into highly managed ridge-to-reef chiefdoms:

-

Oʻahu, Maui, and Kauaʻi anchored dense populations with engineered valleys and pond-coast estates.

-

Consolidated ahupuaʻa governance, monumental heiau, and surplus mobilization furnished the institutional base for later island-wide unifications—while sustaining resilient food systems through the climatic variability of the early Little Ice Age.

West Polynesia (1252 – 1395 CE): Tuʻi Tonga Hegemony, Samoan Councils, and Taputapuātea’s Ritual Commonwealth

Geographic and Environmental Context

West Polynesia includes the Big Island of Hawaiʻi, Tonga, Samoa, Tuvalu, Tokelau, the Cook Islands, and French Polynesia (the Society Islands and the Marquesas).

-

High volcanic archipelagos (Hawaiʻi Island, Tonga, Samoa, Societies, Marquesas) sustained large valleys, leeward plains, and rich reefs.

-

Low atolls (Tuvalu, Tokelau, some Cooks) relied on arboriculture, lagoon fisheries, and exchange.

-

The region straddled the central Pacific voyaging lanes—west to Fiji and Vanuatu, east to the Societies and Marquesas, and north to Hawaiʻi.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

The late Medieval Warm Period eased into the early Little Ice Age (~1300s), bringing greater rainfall variability and occasional cool spells.

-

Cyclones periodically struck the Cooks and Societies; multi-year droughts challenged atolls.

-

Resilience came from diversified ridge-to-reef food systems and inter-island redistribution.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Tonga (Tuʻi Tonga polity):

-

The Tuʻi Tonga line maintained a far-reaching maritime hegemony (c. 1200–1500), projecting ritual and political authority through marriage alliances, tribute voyages, and sacred titles.

-

Tribute flowed from parts of Samoa and the Cooks as well as peripheral partners; high chiefs managed outliers while the royal center staged large ritual feasts.

-

-

Samoa:

-

Power remained distributed among matai (titled heads) and orator groups; great titles balanced districts through councils and ceremonial exchange.

-

Samoan influence permeated the west–east network via marriage, language prestige, and ceremonial protocol (e.g., ʻava rites).

-

-

Society Islands (Ra‘iātea–Tahiti complex):

-

Taputapuātea on Ra‘iātea continued as a pan-Polynesian ritual hub, where chiefs and priests renewed alliances and sacred genealogies; voyaging guilds refreshed routes linking Cooks, Societies, and the Marquesas.

-

-

Marquesas:

-

Intensified valley chiefdoms built large plaza precincts (tōhua), elaborated tattoo and carving traditions, and maintained long-range ties to the Societies.

-

-

Cook Islands, Tuvalu, Tokelau:

-

Atoll and high-island chiefdoms integrated into Tongan and Society networks; some islands specialized in fine mats, canoe components, and salt fish.

-

-

Hawaiʻi Island:

-

Chiefly consolidation accelerated; aliʻi patronized large dryland field systems (e.g., leeward Kona expansions) and fishponds (loko iʻa) on protected coasts.

-

The kapu system tightened labor mobilization for irrigation features, terraces, and temple construction (heiau).

-

Economy and Trade

-

Staples: irrigated taro in wet valleys; dryland complexes of sweet potato, yam, and gourds on leeward slopes; breadfruit–coconut arboriculture on atolls.

-

Aquatic production: large coastal fishponds (loko iʻa) and lagoon fisheries yielded reliable protein; reef management (closures, gear taboos) protected stocks.

-

Prestige exchange:

-

Fine mats (ʻie tōga), red feathers, pearl shell, basalt adzes, and sennit cordage moved along Tongan–Samoan–Cook–Society circuits.

-

Hawaiian contributions included high-quality barkcloth and adze stone; south-central routes circulated tools, ornaments, and ritual items among the Societies and Marquesas.

-

-

Redistribution: chiefly feasts converted surplus into alliance and rank; atolls received starch staples and tools in exchange for marine foods and craft goods.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Hydraulic and field systems: stone-lined ditches and terraces in wet valleys; extensive dryland grids (Hawaiʻi Island) leveraging mulch, fallow cycles, and windbreaks.

-

Fishpond engineering: seawalls and sluice gates controlled recruitment and harvest; staggered ponds spread seasonal risk.

-

Vessels & navigation: double-hulled voyaging canoes; wayfinding by stars, swells, cloud forms, seabird behavior; maintained routes binding Tonga–Samoa–Cooks–Societies and selectively north to Hawaiʻi.

-

Craft specializations: adze quarrying and finishing, barkcloth beating, sennit ropework, shell and wood carving.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Tonga–Samoa–Cooks–Societies arc: the core political–ritual corridor of the age, anchored by Taputapuātea convocations.

-

Marquesan links: voyages to the Societies for ritual and marriage ties; exchange of specialists and regalia.

-

Hawaiʻi Island: robust inter-island Hawaiian traffic; selective long-distance links persisted through shared voyaging lore rather than regular southbound circuits.

-

Atoll shuttles (Tuvalu, Tokelau): lifelines for salt fish, fiber, and mats.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Divine kingship: the Tuʻi Tonga embodied cosmic order; court ritual fused genealogy, sacrifice, and sea power.

-

Taputapuātea: pan-Polynesian rites renewed sacred genealogies and voyaging covenants; marae federations bound chiefs across archipelagos.

-

Hawaiʻi Island: monumental heiau (agriculture, healing, war) and the kapu system regulated ecology and hierarchy; aliʻi sanctity expressed in feather regalia and temple dedications.

-

Samoa & Marquesas: oratory, tattoo, and plaza ceremonies affirmed lineage prestige and sacred authority.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Portfolio food webs (valley irrigation + dryland grids + fishponds + reef/lagoon fisheries) buffered climatic swings of the early Little Ice Age.

-

Ritual closures and calendrical taboos protected spawning grounds and allowed pond/reef recovery.

-

Inter-island reciprocity—tribute, marriage alliances, convoyed voyages—redistributed surplus after cyclones or droughts.

-

Chiefly labor organization maintained large infrastructures (ponds, terraces, seawalls), enabling quick post-storm repairs.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395, West Polynesia was a knit archipelagic commonwealth:

-

Tuʻi Tonga dominance set the political tempo; Taputapuātea sustained a shared ritual order.

-

Samoan councils, Society–Marquesas cult centers, and Hawaiʻi Island agro-aquatic estates all reached new scales of complexity.

-

The combination of engineered landscapes, voyaging diplomacy, and sacred governance provided durable buffers against climatic variability and framed the region’s trajectories into the later medieval centuries.

Micronesia (1252–1395 CE):

Navigators, Shrines, and Atoll Confederacies

Geographic and Environmental Framework

During the Lower Late Medieval Age, Micronesia stretched across the western and central Pacific, forming a vast constellation of coral atolls, volcanic high islands, and limestone plateaus.

It encompassed the Mariana Islands, Palau, and Yap in the west, extending through Kosrae, Nauru, Kiribati, and the Marshall Islands to the east—a maritime realm bound by ocean corridors, exchange alliances, and sacred navigation.

-

High islands such as Kosrae, Palau, and Yap offered fertile soils, freshwater streams, and reef-fringed lagoons suited to intensive horticulture.

-

Atolls of the Marshalls and Gilberts sustained communities on thin coral soils through arboriculture, taro-pit cultivation, and reef fishing.

-

Uplifted limestone islands, including Nauru and the northern Marianas, offered limited agriculture but abundant fisheries and nesting seabirds.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The gradual cooling of the Little Ice Age after c. 1300 CE brought greater rainfall variability, stronger typhoons, and intensified ENSO drought cycles.

-

High islands such as Yap, Palau, and Kosrae provided reliable rainfall, enabling irrigation and food storage.

-

Low atolls, vulnerable to drought and storm surge, relied on deep babai (swamp taro) pits breadfruit preservation, and inter-island aid.

-

These environmental contrasts fostered regional systems of tribute, reciprocity, and navigation, ensuring collective resilience.

Societies and Political Developments

Across Micronesia, communities organized around hereditary chiefs, ritual specialists, and federated systems of exchange that balanced autonomy and interdependence.

-

Kosrae: Centralized kingship (tokosra) reached its architectural zenith at Lelu, a coral-block city with causeways, canals, and walled compounds. Sacred rulers coordinated irrigation, tribute, and monumental labor, embodying divine order in stone.

-

Yap: Became the hub of the sawei system—a sphere of tribute linking hundreds of Caroline atolls. Outer islands sent offerings of breadfruit paste, mats, and shells to Yap in return for navigational training, protection, and prestige goods. Chiefs controlled rai (stone money) quarries, whose immense carved disks, transported from Palau, symbolized wealth and ancestral authority.

-

Palau: Clan-based chiefdoms built stone terraces and shrines, managed taro swamps, and developed rice cultivation—unique in Oceania. Large men’s houses (bai) served as political and ritual centers, their carved gables recounting creation myths and lineage history.

-

Mariana Islands: Village polities under matrilineal clans expanded latte-stone architecture, erecting megalithic pillars as foundations for chiefly dwellings and public halls. Warfare over land and reef tenure reflected growing population pressures.

-

Marshall Islands and Kiribati: Organized under hereditary iroij (paramount chiefs) and council elders meeting in the maneaba (assembly house). Their authority rested on inter-atoll cooperation and mastery of navigation.

-

Nauru: Maintained small clan communities combining gardens, coconut groves, and reef fishing, integrated into passing canoe circuits.

Economy and Exchange Networks

Micronesian economies combined tree-crop horticulture, taro irrigation, reef fishing, and reciprocal exchange that linked high islands and atolls into one of the most dynamic maritime systems of the Pacific.

-

Staples: coconut, breadfruit, pandanus, yam, and taro; babai cultivated in deep pits on atolls and irrigated terraces on high islands.

-

Fisheries: lagoon netting, fish weirs, turtle hunts, and pelagic trolling for tuna and bonito; breadfruit and fish paste preserved for dry seasons.

-

Trade circuits:

-

The sawei network radiated from Yap across the western Carolines, redistributing food, craft goods, and navigational lore.

-

Palau exported rai disks, fine mats, and carved ornaments; Kosrae sent timber, taro, and canoes in exchange for shells and cordage.

-

Marshalls and Gilberts sustained inter-atoll reciprocity, exchanging salt fish, mats, and fiber goods between drought-stricken and surplus islets.

-

Guam and the southern Marianas served as waystations for trade and ceremonial alliance.

-

Subsistence and Technology

-

Irrigation systems: engineered taro pondfields in Palau and Kosrae, with embankments, canals, and drainage controls.

-

Architecture: coral-block citadels at Lelu, bai houses in Palau, latte stones in the Marianas, and stone-money banks in Yap embodied political authority.

-

Navigation: outrigger canoes and crab-claw sails; navigators trained to read stars, ocean swells, and bird flight patterns—maintaining oral “stick charts” that mapped the sea through memory.

-

Craft industries: shell adzes, fiber nets, obsidian and coral tools, carved gables, and ritual masks combined utility with cosmological meaning.

Belief and Symbolism

Micronesian cosmology interwove ancestral veneration, navigation, and sacred geography:

-

Yap: Rai stones embodied the spirit of heroic voyages; each disk’s journey conferred sacred legitimacy.

-

Palau: Creation myths, clan totems, and ancestor shrines were carved into bai houses, merging art, ritual, and governance.

-

Kosrae: The stone city of Lelu mirrored the cosmic order, linking human hierarchy with divine kingship.

-

Marianas: Latte stones symbolized endurance and lineage, while rituals honored sea spirits and agricultural fertility.

-

Marshalls and Kiribati: Navigation was sacralized; voyagers invoked sea deities and star gods before departures.

Every voyage, crop, or monument reaffirmed the spiritual balance between land, ocean, and ancestry.

Adaptation and Resilience

Micronesians sustained complex strategies for survival under climatic uncertainty:

-

Diversified subsistence: blending arboriculture, fishing, and taro cultivation across ecological niches.

-

Reciprocity networks: the sawei system and inter-atoll gift exchanges redistributed surplus and stabilized communities after storms or droughts.

-

Monumental architecture: Latte, bai, and rai embodied social cohesion and ritual authority, reinforcing unity after environmental crises.

-

Navigation schools: safeguarded knowledge that linked scattered islands into a shared maritime world.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395 CE, Micronesia had matured into an integrated oceanic system of tribute, navigation, and sacred monumentality:

-

Yap projected its influence through the sawei network, uniting hundreds of islands under cycles of exchange and ritual diplomacy.

-

Palau flourished as a center of carved artistry, irrigated taro, and early rice cultivation.

-

Kosrae stood as a volcanic stronghold of stone kingship, while the Marianas, Marshalls, and Gilberts perfected the governance of atolls through assemblies, voyaging, and preservation.

Together, these societies exemplified the balance of hierarchy and reciprocity, intellect and faith—an enduring maritime civilization that transformed the scattered isles of the western Pacific into a coherent world of stone, sail, and memory.